de Pizan, Christine

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

* Le Livre de la cité des dames (1405) (Book of the City of Women) | * Le Livre de la cité des dames (1405) (Book of the City of Women) | ||

* Le Livre des trois vertus (1405) (Book of the Three Virtues) | * Le Livre des trois vertus (1405) (Book of the Three Virtues) | ||

| − | * L'Avision de Christine (1405) (An inspirational piece on de Pizan's commentary | + | * L'Avision de Christine (1405) (An inspirational piece on de Pizan's commentary on the writings of Thomas Aquinas) |

* Livre du corps de policie (1407) (Book of the Rules of Policy) | * Livre du corps de policie (1407) (Book of the Rules of Policy) | ||

* Livre de la mutation de fortune (1410) (The Book of the Change of Fortune) | * Livre de la mutation de fortune (1410) (The Book of the Change of Fortune) | ||

Revision as of 21:03, 9 December 2008

Christine de Pizan (also seen as de Pisan) (1363–c.1434) was a writer and analyst of the medieval era who strongly challenged misogyny and stereotypes that were prevalent in the male-dominated realm of the arts. De Pizan completed forty-one pieces during her thirty-year career (1399–1429). She earned her accolade as Europe’s first professional woman writer. Her success stems from a wide range of innovative writing and rhetorical techniques that critically challenged renowned male writers-such as Jean de Meun who, to Pizan’s dismay, incorporated misogynist beliefs within their literary works.

In recent decades, de Pizan's work has been returned to prominence by the efforts of scholars such as Charity Cannon Willard and Earl Jeffrey Richards. Certain scholars have argued that she should be seen as an early feminist who efficiently used language to convey that women could play an important role within society, although this characterization has been challenged by other critics who claim either that it is an anachronistic use of the word, or that her beliefs were not progressive enough to merit such a designation.

Life

Christine de Pizan was born in Venice, Italy 1364. She was the daughter of Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano (Thomas de Pizan; named for the family's origins in the town of Pisano), a physician, professor of astrology, and Councilor of the Republic of Venice. Following Christine’s birth, Thomas de Pizan accepted an appointment to the court of Charles V of France, as the king’s astrologer, alchemist, and physician. In this atmosphere, Christine was able to pursue her intellectual interests. She successfully educated herself by immersing herself in languages, in the rediscovered classics and humanism of the early Renaissance, and in Charles V’s royal archive that housed a vast number of manuscripts. De Pizan did not, however, assert her intellectual abilities, or establish her authority as a writer until after she was widowed at the age of twenty-four.

Christine de Pizan married Etienne du Castel, a royal secretary to the court, at the age of fifteen. She bore three children, a daughter (who went to live at the Dominican Abbey in Poissy in 1397 as a companion to the king's daughter, Marie), a son Jean, and another child who died in childhood. De Pizan’s familial life was threatened in 1390, however, when her husband, while in Beauvais on a mission with the king, suddenly died in an epidemic. Following du Castel’s death, de Pizan was left to support a large household, and to pay off her husband's extensive debts. She was fatherless and widowed, needing to support three children, her mother and a niece. When she tried to collect money due to her husband’s estate, she faced complicated lawsuits regarding the recovery of salary due to her husband. In order to support herself and her family, de Pizan turned to writing. At first her writing was a form of therapy to deal with the misery of widowhood. De Pizan's personal reflections led to the creation of a new style of poetry lamenting widowhood.

Some believe that de Pizan worked as a copyist for manuscripts in the expanding book trade in the decade following her husband's death and before she published any of her texts. Illumination and transcription were two professions still open to women even though job opportunities for women decreased in the fourteenth century. Yet women did not work along side men for fear of losing their reputation, thus de Pizan would have worked along side other women in the field or in her own home.

By 1393, she was writing love ballads, which caught the attention of wealthy patrons within the court who were intrigued by the novelty of a female writer and who had her compose texts about their romantic exploits. De Pizan's output during this period was prolific. Between 1393 and 1412, she composed over three hundred ballads, and many more shorter poems. She also wrote a highly regarded biography of Charles V of France.

De Pizan’s participation in a literary quarrel, 1401–1402, allowed her to move beyond the courtly circles, and ultimately established her status as a writer concerned with the position of women in society. During these years, she involved herself in a renowned literary debate, the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose” ("Questions concerning the Romance of the Rose"). Pizan helped to instigate this particular debate when she began to question the literary merits of Jean de Meun’s Romance of the Rose. Written in the thirteenth century, the Romance of the Rose satirizes the conventions of courtly love while also critically depicting women as nothing more than seducers. De Pizan specifically objected to the use of vulgar terms in Jean de Meun’s allegorical poem. She argued that these terms denigrated the proper and natural function of sexuality, and that such language was inappropriate for female characters. According to de Pizan, noble women did not use such language. Her critique primarily stems from her belief that Jean de Meun was purposely slandering women through the debated text.

In the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose,” de Pizan responded to Jean de Montreuil, who had written her a treatise defending the misogynist sentiments in the Romance of the Rose. She begins by claiming that her opponent was an “expert in rhetoric” as compared to herself “a woman ignorant of subtle understanding and agile sentiment.” In this particular apologetic response, de Pizan belittles her own style. She is employing a rhetorical strategy by writing against the grain of her meaning, also known as antiphrasis. Her ability to employ rhetorical strategies continued when de Pizan began to compose literary texts following the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose.”

The debate itself is quite extensive and by the end of it, the principal issue was no longer Jean de Meun’s literary capabilities. Instead, due to the participation of de Pizan in the debate, the focus had shifted to the unjust slander of women within literary texts. This dispute helped to establish de Pizan’s reputation as a female intellectual who could assert herself effectively and defend her claims in the male-dominated literary realm. De Pizan continued to counter abusive literary treatments of women in other works-all of which had to be copied by hand.

Work

By 1405, Christine de Pizan had completed her most successful literary works, The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies, or The Book of the Three Virtues. The first of these shows the importance of women’s past contributions to society, and the second strives to teach women of all estates how to cultivate useful qualities in order to counteract the growth of misogyny.

In her The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) de Pizan creates a symbolic city in which women are appreciated and defended. De Pizan, having no female literary tradition to call upon, constructs three allegorical foremothers: Reason, Justice, and Rectitude. She enters into a dialogue, a movement between question and answer, with these allegorical figures that is from a completely female perspective. These constructed women lift de Pizan up from her despair over the misogyny prevalent in her time. Together, they create a forum to speak on issues of consequence to all women. Only female voices, examples and opinions provide evidence within this text. De Pizan, through Lady Reason in particular, argues that stereotypes of woman can be sustained only if women are prevented from entering the dominant male-oriented conversation. Overall, de Pizan hoped to establish truths about women that contradicted the negative stereotypes that she had identified in previous literature. She did this successfully by creating her literary foremothers who helped her to formulate a female dialogue that celebrated women and their accomplishments.

This unique text provides powerful positive images of women—ranging from warriors, inventors, and scholars to prophetesses, artists, and saints—but also offers fascinating insight into the debates and controversies about the role of women in medieval culture where women were usually seen as the source of vice.

The Treasure of the City of Ladies/Book of the Three Virtues (1405) highlights the persuasive effect of women’s speech and actions in everyday life. In this particular text, de Pizan argues that women must recognize and promote their ability to make peace. This ability will allow women to mediate between husband and subjects. She also claims that slanderous speech erodes one’s honor and threatens the sisterly bond among women. De Pizan then argues that "skill in discourse should be a part of every woman’s moral repertoire." De Pizan understood that a woman’s influence is realized when her speech accords value to chastity, virtue, and restraint. De Pizan proved that rhetoric is a powerful tool that women could employ to settle differences and to assert themselves. Overall, she presented a concrete strategy that allowed all women, regardless of their status, to undermine the dominant patriarchal discourse. She has harsh words for lazy, ostentatious clotheshorses but recommends "justifiable hypocrisy" to prevail over schemers. It is like a manual of good behavior with moral and practical advice, not only to noble women, but to women of all classes while giving a rare glimpse into the daily life and household management of medieval households.

By this time de Pizan was doing well financially so much so that she writes:

I thought I would multiply this work throughout the world in various copies, whatever the cost might be, and present it in particular places to queens, princesses, and noble ladies. Through their efforts, it will be the more honored and praised, as is fitting, and better circulated among other women. I already have started this process; so that this book will be examined, read and published in all countries. (The Book of Three Virtues, p. 224)

Lists of artisans seldom mentioned women, even though there were some who worked in the field. De Pizan specifically sought out other women to collaborate with in the creation of her work. She makes special mention of a manuscript illuminator known only as Anastasia who she described as the most talented of her day.

I know a woman...Anastasia, who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris-where the best in the world are found-who can surpass her...People cannot stop talking about her...she has executed several things for me, which stand out among the ornamental borders of the great masters. (City of Ladies p. 85) [1]

Her Collected Works which she presented to Queen Isabeau of France, between 1410-1415 (now in the British Library) was her final supervision of an illuminated manuscript. This work reflects the words of a woman, transcribed by a woman, illustrated by a woman artist, and presented to a Queen in court; it seems that this is the heart of de Pizan's "New Kingdom of Femininity" (City of Ladies, p. 117).

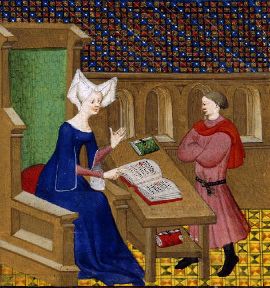

Interesting to note, is the fact that de Pizan appears in her typical simple dress in many of the illuminations in her books. Some of these scenes are apparently not done by men due to the candid and personal images of the women. No woman would allow a man to see her so informally.

Also from this time, de Pizan moves to writing about good government which was a fashionable genre of art and literature. De Pizan's concern for politics begins quietly with her 1403 work The Path of Long Study, about the proper behavior of princes and chivalry, establishing her contemporary scholarly reputation. But she never names names or accuses any leader of wrong doing.

But in 1412, during the threat of civil war by the French noble factions, de Pizan writes The Lamentation on the Evils That Have Befallen France and does name those aristocrats who she feels are at fault. Interesting, this is the time when she stops being a publisher. Perhaps her work writing against misogynist texts was acceptable or advising the leadership on ethical behavior, but when she openly scolds the princely powers about their bad behavior, it is no longer acceptable. Her writings put her in a precarious position during the lead up to the French civil war. She had patrons on both sides of the struggle but in 1418 she leaves Paris, never to return. She spent the remainder of her life enclosed in an abbey "due to treachery."[2]

De Pizan’s final work was a poem eulogizing Joan of Arc (who still lived at the time), the peasant girl who took a very public role in organizing French military resistance to English domination in the early fifteenth century. This unique work vividly caught the rise of optimism of the French soldiers. It also reflected the wonder and gratitude at the miraculous intervention of divine Providence in the person of Jeanne which the populous shared.

Written in 1429, The Tale of Joan of Arc celebrates the appearance of a woman military leader who, according to de Pizan, vindicated and rewarded all women’s efforts to defend their own sex. After completing this particular poem of 61 verses, it seems that de Pizan, at the age of sixty-five, decided to end her literary career. The exact date of her death is unknown. However, her death did not diminish appreciation for her renowned literary works. Instead, her legacy continued on because of the voice she established as an authoritative rhetorician.

Legacy

Whether Christine de Pizan was a pre-feminist or not, she stands out as a unique woman writer and analyst of the fourteenth century who also contributed to the rhetorical tradition as a woman counteracting the dominant male discourse of the time. Her feminism includes raising a family and a lost beloved husband, and stresses that the misogynistic language that some writers used was in error of the real facts about women.

Rhetorical scholars have extensively studied her persuasive strategies. It has been concluded that de Pizan successfully forged a rhetorical identity for herself, and also encouraged all women to embrace this identity by counteracting misogynist thinking through the powerful tool of persuasive dialogue. Her writings are still read today by women and men alike in many languages.

Selected Bibliography

- L'Épistre au Dieu d'amours (1399) (Epistle on the Love of God)

- L'Épistre de Othéa a Hector (1399-1400)

- Dit de la Rose (1402) (Tale of the Rose)

- Cent Ballades d'Amant et de Dame, Virelyas, Rondeaux (1402) (100 Ballads)

- Le Chemin de long estude (1403) (Book of Long Study)

- La Pastoure (1403)

- Le Livre des fais et bonners meurs du sage roy Charles V (1404) (Biography of King Charles V)

- Le Livre de la cité des dames (1405) (Book of the City of Women)

- Le Livre des trois vertus (1405) (Book of the Three Virtues)

- L'Avision de Christine (1405) (An inspirational piece on de Pizan's commentary on the writings of Thomas Aquinas)

- Livre du corps de policie (1407) (Book of the Rules of Policy)

- Livre de la mutation de fortune (1410) (The Book of the Change of Fortune)

- Livre de paix (1413) (Book of Peace)

- Ditié de Jehanne d'Arc (1429) (The Tale of Joan d'Arc)

See also

- Isabeau of Bavaria

- Joan of Arc

- Women's history

Notes

- ↑ Ripely, Doré. Christine de Pizan: An illuminated Voice Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ↑ Ditie de Jehanne d'Arc - French w/ English translation Retrieved December 7, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell, Karlyn K., Three Tall Women: Radical Challenges to Criticism, Pedagogy, and Theory, Allyn and Bacon, 2003. ISBN 9780205375912

- de Pizan, Dhristine and Rosalind Brown-Grant, ed. The Book of the City of Ladies, Penguin Classics, 2000. ISBN 9780140446890

- de Pisan, Christine, Madeleine Pelner Cosman (authors), and Charity Cannon Willard (trans). A Medieval Woman's Mirror of Honor: The Treasury of the City of Ladies, Bard Hall Press, 2001. ISBN 9780892551354

- Green, Karen, and Mews, Constant, eds, Healing the Body Politic: The Political Thought of Christine de Pizan, Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2005. ISBN 9782503516363

- Redfern, Jenny, "Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric" in Lunsford, Andrea A, ed. Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women and in the Rhetorical Tradition, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995. ISBN 9780822955535

- Richards, Earl Jeffrey, ed. Reinterpreting Christine de Pizan, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992. ISBN 9780820313078

- Quilligan, Maureen, The Allegory of Female Authority: Christine de Pizan's "Cité des Dames". New York: Cornell University Press, 1991. ISBN 9780801497889

- Willard, Charity C., ed. The "Livre de Paix" of Christine de Pisan: A Critical Edition, The Hague: Mouton, 1958. ASIN B000HTLU76

- ___________________ Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works, George Braziller, 1990. ISBN 9780892551521

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2008.

- Riley, Doré. Christine de Pizan: An Illuminated Voice

- Ditie de Jehanne d'Arc - French w/ English translation

- Comprehensive bibliography of her works, including listings of the manuscripts, editions, translations, and essays in French at Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (Arlima)

Warning: Default sort key "Pizan, Christine de" overrides earlier default sort key "de Pizan, Christine".

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.