Post-traumatic stress disorder

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | |

| |

| Symptoms | Disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams related to the event; mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues; efforts to avoid trauma-related situations; increased fight-or-flight response[1] |

|---|---|

| Complications | Self-harm, suicide[2] |

| Duration | > 1 month[1] |

| Causes | Exposure to a traumatic event[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[2] |

| Treatment | Counseling, medication[3] |

| Medication | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor[4] |

| Frequency | 8.7% (lifetime risk); 3.5% (12-month risk) (US)[5] |

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[lower-alpha 1] is a mental and behavioral disorder[6] that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats on a person's life.[1][7] Symptoms may include disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams related to the events, mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues, attempts to avoid trauma-related cues, alterations in the way a person thinks and feels, and an increase in the fight-or-flight response.[1][3] These symptoms last for more than a month after the event.[1] Young children are less likely to show distress but instead may express their memories through play.[1] A person with PTSD is at a higher risk of suicide and intentional self-harm.[2][8]

Most people who experience traumatic events do not develop PTSD.[2] People who experience interpersonal violence such as rape, other sexual assaults, being kidnapped, stalking, physical abuse by an intimate partner, and incest or other forms of childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop PTSD than those who experience non-assault based trauma, such as accidents and natural disasters.[9][10][11] Those who experience prolonged trauma, such as slavery, concentration camps, or chronic domestic abuse, may develop complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). C-PTSD is similar to PTSD but has a distinct effect on a person's emotional regulation and core identity.[12]

Prevention may be possible when counselling is targeted at those with early symptoms but is not effective when provided to all trauma-exposed individuals whether or not symptoms are present.[2] The main treatments for people with PTSD are counselling (psychotherapy) and medication.[3][13] Antidepressants of the SSRI or SNRI type are the first-line medications used for PTSD and are moderately beneficial for about half of people.[4] Benefits from medication are less than those seen with counselling.[2] It is not known whether using medications and counselling together has greater benefit than either method separately.[2][14] Medications, other than some SSRIs or SNRIs, do not have enough evidence to support their use and, in the case of benzodiazepines, may worsen outcomes.[15][16]

In the United States, about 3.5% of adults have PTSD in a given year, and 9% of people develop it at some point in their life.[1] In much of the rest of the world, rates during a given year are between 0.5% and 1%.[1] Higher rates may occur in regions of armed conflict.[2] It is more common in women than men.[3]

Symptoms of trauma-related mental disorders have been documented since at least the time of the ancient Greeks.[17] A few instances of evidence of post-traumatic illness have been argued to exist from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such as the diary of Samuel Pepys, who described intrusive and distressing symptoms following the 1666 Fire of London.[18] During the world wars, the condition was known under various terms, including 'shell shock', 'war nerves', neurasthenia and 'combat neurosis'.[19][20] The term "post-traumatic stress disorder" came into use in the 1970s in large part due to the diagnoses of U.S. military veterans of the Vietnam War.[21] It was officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III).[22] Template:TOC limit

Terminology

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders does not hyphenate "post" and "traumatic", thus, the DSM-5 lists the disorder as posttraumatic stress disorder. However, many scientific journal articles and other scholarly publications do hyphenate the name of the disorder, viz., "post-traumatic stress disorder".[23] Dictionaries also differ with regard to the preferred spelling of the disorder with the Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged using the hyphenated spelling, and the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition and the Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary giving the non-hyphenated spelling.[24]

History of the terminology

The 1952 edition of the DSM-I includes a diagnosis of "gross stress reaction", which has similarities to the modern definition and understanding of PTSD.[25] Gross stress reaction is defined as a normal personality using established patterns of reaction to deal with overwhelming fear as a response to conditions of great stress.[26] The diagnosis includes language which relates the condition to combat as well as to "civilian catastrophe".[26]

Early in 1978, the diagnosis term "post-traumatic stress disorder" was first recommended in a working group finding presented to the Committee of Reactive Disorders.[27] The condition was described in the DSM-III (1980) as posttraumatic stress disorder.[25][27] In the DSM-IV, the spelling "posttraumatic stress disorder" is used, while in the ICD-10, the spelling is "post-traumatic stress disorder".[28]

The addition of the term to the DSM-III was greatly influenced by the experiences and conditions of U.S. military veterans of the Vietnam War.[29] Owing to its association with the war in Vietnam, PTSD has become synonymous with many historical war-time diagnoses such as railway spine, stress syndrome, nostalgia, soldier's heart, shell shock, battle fatigue, combat stress reaction, or traumatic war neurosis.[30][31] Some of these terms date back to the 19th century, which is indicative of the universal nature of the condition. In a similar vein, psychiatrist Jonathan Shay has proposed that Lady Percy's soliloquy in the William Shakespeare play Henry IV, Part 1 (act 2, scene 3, lines 40–62[32]), written around 1597, represents an unusually accurate description of the symptom constellation of PTSD.[33]

The correlations between combat and PTSD are undeniable; according to Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker, "One-tenth of mobilized American men were hospitalized for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945, and, after thirty-five days of uninterrupted combat, 98% of them manifested psychiatric disturbances in varying degrees."[34] In fact, much of the available published research regarding PTSD is based on studies done on veterans of the war in Vietnam. A study based on personal letters from soldiers of the 18th-century Prussian Army concludes that combatants may have had PTSD.[35] Aspects of PTSD in soldiers of ancient Assyria have been identified using written sources from 1300 to 600 B.C.E. These Assyrian soldiers would undergo a three-year rotation of combat before being allowed to return home, and were reported to have faced immense challenges in reconciling their past actions in war with their civilian lives.[36] Connections between the actions of Viking berserkers and the hyperarousal of post-traumatic stress disorder have also been drawn.[37]

The researchers from the Grady Trauma Project highlight the tendency people have to focus on the combat side of PTSD: "less public awareness has focused on civilian PTSD, which results from trauma exposure that is not combat related... " and "much of the research on civilian PTSD has focused on the sequelae of a single, disastrous event, such as the Oklahoma City bombing, September 11th attacks, and Hurricane Katrina".[38] Disparity in the focus of PTSD research affects the already popular perception of the exclusive interconnectedness of combat and PTSD. This is misleading when it comes to understanding the implications and extent of PTSD as a neurological disorder. Dating back to the definition of Gross stress reaction in the DSM-I, civilian experience of catastrophic or high stress events is included as a cause of PTSD in medical literature. The 2014 National Comorbidity Survey reports that "the traumas most commonly associated with PTSD are combat exposure and witnessing among men and rape and sexual molestation among women."[39]

Because of the initial overt focus on PTSD as a combat related disorder when it was first fleshed out in the years following the war in Vietnam, in 1975 Ann Wolbert Burgess and Lynda Lytle Holmstrom defined rape trauma syndrome (RTS) in order to draw attention to the striking similarities between the experiences of soldiers returning from war and of rape victims.[40] This paved the way for a more comprehensive understanding of causes of PTSD.

After PTSD became an official psychiatric diagnosis with the publication of DSM-III (1980), the number of personal injurylawsuits (tort claims) asserting the plaintiff suffered from PTSD increased rapidly. However, triers of fact (judges and juries) often regarded the PTSD diagnostic criteria as imprecise, a view shared by legal scholars, trauma specialists, forensic psychologists, and forensic psychiatrists. Professional discussions and debates in academic journals, at conferences, and between thought leaders, led to a more clearly-defined set of diagnostic criteria in DSM-IV, particularly the definition of a "traumatic event".[41]

The DSM-IV classified PTSD under anxiety disorders, but the DSM-5 created a new category called "trauma and stressor-related disorders", in which PTSD is now classified.[1]

Complex PTSD

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD; also known as complex trauma disorder)[42] is a psychological disorder that is theorized to develop in response to exposure to a series of traumatic events in a context in which the individual perceives little or no chance of escape, and particularly where the exposure is prolonged or repetitive.[43]<span title="{{#invoke:DecodeEncode|encode|s={{#invoke:Plain text|main|1=Page / location: {{#invoke:String2|hyphen2dash|}}|encode=false}}|charset=<>"}}">: {{#invoke:String2|hyphen2dash|| }}  It is not yet recognized by the American Psychiatric Association or the DSM-5 as a valid disorder, although was added to the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).[43] In addition to the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an individual with C-PTSD experiences emotional dysregulation, negative self-beliefs and feelings of shame, guilt or failure regarding the trauma, and interpersonal difficulties.[43] C-PTSD relates to the trauma model of mental disorders and is associated with chronic sexual, psychological, and physical abuse or neglect, or chronic intimate partner violence, bullying, victims of kidnapping and hostage situations, indentured servants, victims of slavery and human trafficking, sweatshop workers, prisoners of war, concentration camp survivors, and prisoners kept in solitary confinement for a long period of time, or defectors from authoritarian religions. Situations involving captivity/entrapment (a situation lacking a viable escape route for the victim or a perception of such) can lead to C-PTSD-like symptoms, which can include prolonged feelings of terror, worthlessness, helplessness, and deformation of one's identity and sense of self.[44] C-PTSD is linked to adverse childhood experiences,[45][46] especially among survivors of foster care.[47]

C-PTSD has also been referred to as Enduring Personality Change after Catastrophic Event (EPCACE).[48][49] and/or Disorders of Extreme Stress - not otherwise specified (DESNOS)[50]

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD; also known as complex trauma disorder)[42] is a psychological disorder that can develop in response to exposure to a series of traumatic events in a context in which the individual perceives little or no chance of escape, and particularly where the exposure is prolonged or repetitive.[43]<span title="{{#invoke:DecodeEncode|encode|s={{#invoke:Plain text|main|1=Page / location: {{#invoke:String2|hyphen2dash|}}|encode=false}}|charset=<>"}}">: {{#invoke:String2|hyphen2dash|| }}  In addition to the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an individual with C-PTSD experiences emotional dysregulation, negative self-beliefs and feelings of shame, guilt or failure regarding the trauma, and interpersonal difficulties.[43] C-PTSD relates to the trauma model of mental disorders and is associated with chronic sexual, psychological, and physical abuse or neglect, or chronic intimate partner violence, victims of kidnapping and hostage situations, indentured servants, victims of slavery and human trafficking, sweatshop workers, prisoners of war, concentration camp survivors, residential school survivors and prisoners kept in solitary confinement for a long period of time, or defectors from authoritarian religions. Situations involving captivity/entrapment (a situation lacking a viable escape route for the victim or a perception of such) can lead to C-PTSD-like symptoms, which can include prolonged feelings of terror, worthlessness, helplessness, and deformation of one's identity and sense of self.[44]

C-PTSD has also been referred to as disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified or DESNOS.[51]

Some researchers believe that C-PTSD is distinct from, but similar to, PTSD, somatization disorder, dissociative identity disorder, and borderline personality disorder.[44] Its main distinctions are a distortion of the person's core identity and significant emotional dysregulation.[52] It was first described in 1992 by American psychiatrist and scholar Judith Lewis Herman in her book Trauma & Recovery and an accompanying article.[44][53][54]

The disorder is included in the World Health Organization's (WHO) eleventh revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11). The C-PTSD criteria has not yet gone through the private approval board of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Complex PTSD is also recognized by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Healthdirect Australia (HDA), and the British National Health Service (NHS).

Symptoms

Symptoms of PTSD generally begin within the first three months after the inciting traumatic event, but may not begin until years later.[1][3] In the typical case, the individual with PTSD persistently avoids either trauma-related thoughts and emotions or discussion of the traumatic event and may even have amnesia of the event.[1] However, the event is commonly relived by the individual through intrusive, recurrent recollections, dissociative episodes of reliving the trauma ("flashbacks"), and nightmares (50 to 70%[55]).[56] While it is common to have symptoms after any traumatic event, these must persist to a sufficient degree (i.e., causing dysfunction in life or clinical levels of distress) for longer than one month after the trauma to be classified as PTSD (clinically significant dysfunction or distress for less than one month after the trauma may be acute stress disorder).[1][57][58][59] Some following a traumatic event experience post-traumatic growth.[60]

Risk factors

Persons considered at risk include combat military personnel, victims of natural disasters, concentration camp survivors, and victims of violent crime. Persons employed in occupations that expose them to violence (such as soldiers) or disasters (such as emergency service workers) are also at risk.[62] Other occupations that are at higher risk include police officers, firefighters, ambulance personnel, health care professionals, train drivers, divers, journalists, and sailors, in addition to people who work at banks, post offices or in stores.[63]

Trauma

PTSD has been associated with a wide range of traumatic events. The risk of developing PTSD after a traumatic event varies by trauma type[64][65] and is highest following exposure to sexual violence (11.4%), particularly rape (19.0%).[66] Men are more likely to experience a traumatic event (of any type), but women are more likely to experience the kind of high-impact traumatic event that can lead to PTSD, such as interpersonal violence and sexual assault.[67]

Motor vehicle collision survivors, both children and adults, are at an increased risk of PTSD.[68][69] Globally, about 2.6% of adults are diagnosed with PTSD following a non-life-threatening traffic accident, and a similar proportion of children develop PTSD.[66] Risk of PTSD almost doubles to 4.6% for life-threatening auto accidents.[66] Females were more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD following a road traffic accident, whether the accident occurred during childhood or adulthood.[68][69]

Post-traumatic stress reactions have been studied in children and adolescents.[70] The rate of PTSD might be lower in children than adults, but in the absence of therapy, symptoms may continue for decades.[71] One estimate suggests that the proportion of children and adolescents having PTSD in a non-wartorn population in a developed country may be 1% compared to 1.5% to 3% of adults.[71] On average, 16% of children exposed to a traumatic event develop PTSD, varying according to type of exposure and gender.[72] Similar to the adult population, risk factors for PTSD in children include: female gender, exposure to disasters (natural or manmade), negative coping behaviours, and/or lacking proper social support systems.[73]

Predictor models have consistently found that childhood trauma, chronic adversity, neurobiological differences, and familial stressors are associated with risk for PTSD after a traumatic event in adulthood.[74][75][76] It has been difficult to find consistently aspects of the events that predict, but peritraumatic dissociation has been a fairly consistent predictive indicator of the development of PTSD.[77] Proximity to, duration of, and severity of the trauma make an impact. It has been speculated that interpersonal traumas cause more problems than impersonal ones,[78] but this is controversial.[79] The risk of developing PTSD is increased in individuals who are exposed to physical abuse, physical assault, or kidnapping.[39][80] Women who experience physical violence are more likely to develop PTSD than men.[39]

Intimate partner violence

An individual that has been exposed to domestic violence is predisposed to the development of PTSD. However, being exposed to a traumatic experience does not automatically indicate that an individual will develop PTSD.[81] There is a strong association between the development of PTSD in mothers that experienced domestic violence during the perinatal period of their pregnancy.[82]

Those who have experienced sexual assault or rape may develop symptoms of PTSD.[83][84] PTSD symptoms include re-experiencing the assault, avoiding things associated with the assault, numbness, and increased anxiety and an increased startle response. The likelihood of sustained symptoms of PTSD is higher if the rapist confined or restrained the person, if the person being raped believed the rapist would kill them, the person who was raped was very young or very old, and if the rapist was someone they knew. The likelihood of sustained severe symptoms is also higher if people around the survivor ignore (or are ignorant of) the rape or blame the rape survivor.[85]

Military service is a risk factor for developing PTSD.[86] Around 78% of people exposed to combat do not develop PTSD; in about 25% of military personnel who develop PTSD, its appearance is delayed.[86]

Refugees are also at an increased risk for PTSD due to their exposure to war, hardships, and traumatic events. The rates for PTSD within refugee populations range from 4% to 86%.[87] While the stresses of war affect everyone involved, displaced persons have been shown to be more so than others.[88]

Challenges related to the overall psychosocial well-being of refugees are complex and individually nuanced. Refugees have reduced levels of well-being and a high rates of mental distress due to past and ongoing trauma. Groups that are particularly affected and whose needs often remain unmet are women, older people and unaccompanied minors.[89] Post-traumatic stress and depression in refugee populations also tend to affect their educational success.[89]

Unexpected death of a loved one

Sudden, unexpected death of a loved one is the most common traumatic event type reported in cross-national studies.[66][90] However, the majority of people who experience this type of event will not develop PTSD. An analysis from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys found a 5.2% risk of developing PTSD after learning of the unexpected death of a loved one.[90] Because of the high prevalence of this type of traumatic event, unexpected death of a loved one accounts for approximately 20% of PTSD cases worldwide.[66]

Life-threatening illness

Medical conditions associated with an increased risk of PTSD include cancer,[91][92][93] heart attack,[94] and stroke.[95] 22% of cancer survivors present with lifelong PTSD like symptoms.[96] Intensive-care unit (ICU) hospitalization is also a risk factor for PTSD.[97] Some women experience PTSD from their experiences related to breast cancer and mastectomy.[98][99][91] Loved ones of those who experience life-threatening illnesses are also at risk for developing PTSD, such as parents of child with chronic illnesses.[100]

Women who experience miscarriage are at risk of PTSD.[101][102][103] Those who experience subsequent miscarriages have an increased risk of PTSD compared to those experiencing only one.[101] PTSD can also occur after childbirth and the risk increases if a woman has experienced trauma prior to the pregnancy.[104][105] Prevalence of PTSD following normal childbirth (that is, excluding stillbirth or major complications) is estimated to be between 2.8 and 5.6% at six weeks postpartum,[106] with rates dropping to 1.5% at six months postpartum.[106][107] Symptoms of PTSD are common following childbirth, with prevalence of 24–30.1%[106] at six weeks, dropping to 13.6% at six months.[108] Emergency childbirth is also associated with PTSD.[109]

Genetics

There is evidence that susceptibility to PTSD is hereditary. Approximately 30% of the variance in PTSD is caused from genetics alone.[77] For twin pairs exposed to combat in Vietnam, having a monozygotic (identical) twin with PTSD was associated with an increased risk of the co-twin's having PTSD compared to twins that were dizygotic (non-identical twins).[110] Women with a smaller hippocampus might be more likely to develop PTSD following a traumatic event based on preliminary findings.[111] Research has also found that PTSD shares many genetic influences common to other psychiatric disorders. Panic and generalized anxiety disorders and PTSD share 60% of the same genetic variance. Alcohol, nicotine, and drug dependence share greater than 40% genetic similarities.[77]

Several biological indicators have been identified that are related to later PTSD development. Heightened startle responses and, with only preliminary results, a smaller hippocampal volume have been identified as possible biomarkers for heightened risk of developing PTSD.[112] Additionally, one study found that soldiers whose leukocytes had greater numbers of glucocorticoid receptors were more prone to developing PTSD after experiencing trauma.[113]

Diagnosis

PTSD can be difficult to diagnose, because of:

- the subjective nature of most of the diagnostic criteria (although this is true for many mental disorders);

- the potential for over-reporting, e.g., while seeking disability benefits, or when PTSD could be a mitigating factor at criminal sentencing[114]

- the potential for under-reporting, e.g., stigma, pride, fear that a PTSD diagnosis might preclude certain employment opportunities;

- symptom overlap with other mental disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder;[115]

- association with other mental disorders such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder;

- substance use disorders, which often produce some of the same signs and symptoms as PTSD; and

- substance use disorders can increase vulnerability to PTSD or exacerbate PTSD symptoms or both; and

- PTSD increases the risk for developing substance use disorders.

- the differential expression of symptoms culturally (specifically with respect to avoidance and numbing symptoms, distressing dreams, and somatic symptoms)[116]

Screening

There are a number of PTSD screening instruments for adults, such as the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)[117][118] and the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5).[119]

There are also several screening and assessment instruments for use with children and adolescents. These include the Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS),[120][121] Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire,[122][123] and UCLA Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for DSM-IV.[124][125]

In addition, there are also screening and assessment instruments for caregivers of very young children (six years of age and younger). These include the Young Child PTSD Screen,[126] the Young Child PTSD Checklist,[126] and the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment.[127]

Assessment

Evidence-based assessment principles, including a multimethod assessment approach, form the foundation of PTSD assessment.[128][129][130]

Diagnostic and statistical manual

PTSD was classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV, but has since been reclassified as a "trauma- and stressor-related disorder" in the DSM-5.[1] The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD include four symptom clusters: re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition/mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.[1][3]

International classification of diseases

The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10 (ICD-10) classifies PTSD under "Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders."[131] The ICD-10 criteria for PTSD include re-experiencing, avoidance, and either increased reactivity or inability to recall certain details related to the event.[131]

The ICD-11 diagnostic description for PTSD contains three components or symptom groups (1) re-experiencing, (2) avoidance, and (3) heightened sense of threat.[132][133] ICD-11 no longer includes verbal thoughts about the traumatic event as a symptom.[133] There is a predicted lower rate of diagnosed PTSD using ICD-11 compared to ICD10 or DSM-5.[133] ICD-11 also proposes identifying a distinct group with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), who have more often experienced several or sustained traumas and have greater functional impairment than those with PTSD.[133]

Differential diagnosis

A diagnosis of PTSD requires that the person has been exposed to an extreme stressor. Any stressor can result in a diagnosis of adjustment disorder and it is an appropriate diagnosis for a stressor and a symptom pattern that does not meet the criteria for PTSD.

The symptom pattern for acute stress disorder must occur and be resolved within four weeks of the trauma. If it lasts longer, and the symptom pattern fits that characteristic of PTSD, the diagnosis may be changed.[56]

Obsessive compulsive disorder may be diagnosed for intrusive thoughts that are recurring but not related to a specific traumatic event.[56]

In extreme cases of prolonged, repeated traumatization where there is no viable chance of escape, survivors may develop complex post-traumatic stress disorder.[53] This occurs as a result of layers of trauma rather than a single traumatic event, and includes additional symptomatology, such as the loss of a coherent sense of self.[134]

Pathophysiology

Neuroendocrinology

PTSD symptoms may result when a traumatic event causes an over-reactive adrenaline response, which creates deep neurological patterns in the brain. These patterns can persist long after the event that triggered the fear, making an individual hyper-responsive to future fearful situations.[57][135] During traumatic experiences, the high levels of stress hormones secreted suppress hypothalamic activity that may be a major factor toward the development of PTSD.[136]

PTSD causes biochemical changes in the brain and body, that differ from other psychiatric disorders such as major depression. Individuals diagnosed with PTSD respond more strongly to a dexamethasone suppression test than individuals diagnosed with clinical depression.[137][138]

Most people with PTSD show a low secretion of cortisol and high secretion of catecholamines in urine,[139] with a norepinephrine/cortisol ratio consequently higher than comparable non-diagnosed individuals.[140] This is in contrast to the normative fight-or-flight response, in which both catecholamine and cortisol levels are elevated after exposure to a stressor.[141]

Brain catecholamine levels are high,[142] and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) concentrations are high.[143][144] Together, these findings suggest abnormality in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

The maintenance of fear has been shown to include the HPA axis, the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic systems, and the connections between the limbic system and frontal cortex. The HPA axis that coordinates the hormonal response to stress,[145] which activates the LC-noradrenergic system, is implicated in the over-consolidation of memories that occurs in the aftermath of trauma.[146] This over-consolidation increases the likelihood of one's developing PTSD. The amygdala is responsible for threat detection and the conditioned and unconditioned fear responses that are carried out as a response to a threat.[77]

The HPA axis is responsible for coordinating the hormonal response to stress.[77] Given the strong cortisol suppression to dexamethasone in PTSD, HPA axis abnormalities are likely predicated on strong negative feedback inhibition of cortisol, itself likely due to an increased sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors.[147] PTSD has been hypothesized to be a maladaptive learning pathway to fear response through a hypersensitive, hyperreactive, and hyperresponsive HPA axis.[148]

Low cortisol levels may predispose individuals to PTSD: Following war trauma, Swedish soldiers serving in Bosnia and Herzegovina with low pre-service salivary cortisol levels had a higher risk of reacting with PTSD symptoms, following war trauma, than soldiers with normal pre-service levels.[149] Because cortisol is normally important in restoring homeostasis after the stress response, it is thought that trauma survivors with low cortisol experience a poorly contained—that is, longer and more distressing—response, setting the stage for PTSD.

It is thought that the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system mediates the over-consolidation of fear memory. High levels of cortisol reduce noradrenergic activity, and because people with PTSD tend to have reduced levels of cortisol, it has been proposed that individuals with PTSD cannot regulate the increased noradrenergic response to traumatic stress.[136] Intrusive memories and conditioned fear responses are thought to be a result of the response to associated triggers. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) has been reported to reduce the release of norepinephrine and has been demonstrated to have anxiolytic properties in animal models. Studies have shown people with PTSD demonstrate reduced levels of NPY, possibly indicating their increased anxiety levels.[77]

Other studies indicate that people with PTSD have chronically low levels of serotonin, which contributes to the commonly associated behavioral symptoms such as anxiety, ruminations, irritability, aggression, suicidality, and impulsivity.[150] Serotonin also contributes to the stabilization of glucocorticoid production.

Dopamine levels in a person with PTSD can contribute to symptoms: low levels can contribute to anhedonia, apathy, impaired attention, and motor deficits; high levels can contribute to psychosis, agitation, and restlessness.[150]

Several studies described elevated concentrations of the thyroid hormone triiodothyronine in PTSD.[151] This kind of type 2 allostatic adaptation may contribute to increased sensitivity to catecholamines and other stress mediators.

Hyperresponsiveness in the norepinephrine system can also be caused by continued exposure to high stress. Overactivation of norepinephrine receptors in the prefrontal cortex can be connected to the flashbacks and nightmares frequently experienced by those with PTSD. A decrease in other norepinephrine functions (awareness of the current environment) prevents the memory mechanisms in the brain from processing the experience, and emotions the person is experiencing during a flashback are not associated with the current environment.[150]

There is considerable controversy within the medical community regarding the neurobiology of PTSD. A 2012 review showed no clear relationship between cortisol levels and PTSD. The majority of reports indicate people with PTSD have elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone, lower basal cortisol levels, and enhanced negative feedback suppression of the HPA axis by dexamethasone.[77][152]

Neuroanatomy

A meta-analysis of structural MRI studies found an association with reduced total brain volume, intracranial volume, and volumes of the hippocampus, insula cortex, and anterior cingulate.[154] Much of this research stems from PTSD in those exposed to the Vietnam War.[155][156]

People with PTSD have decreased brain activity in the dorsal and rostral anterior cingulate cortices and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, areas linked to the experience and regulation of emotion.[157]

The amygdala is strongly involved in forming emotional memories, especially fear-related memories. During high stress, the hippocampus, which is associated with placing memories in the correct context of space and time and memory recall, is suppressed. According to one theory this suppression may be the cause of the flashbacks that can affect people with PTSD. When someone with PTSD undergoes stimuli similar to the traumatic event, the body perceives the event as occurring again because the memory was never properly recorded in the person's memory.[77][158]

The amygdalocentric model of PTSD proposes that the amygdala is very much aroused and insufficiently controlled by the medial prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, in particular during extinction.[159] This is consistent with an interpretation of PTSD as a syndrome of deficient extinction ability.[159][160]

The basolateral nucleus (BLA) of the amygdala is responsible for the comparison and development of associations between unconditioned and conditioned responses to stimuli, which results in the fear conditioning present in PTSD. The BLA activates the central nucleus (CeA) of the amygdala, which elaborates the fear response, (including behavioral response to threat and elevated startle response). Descending inhibitory inputs from the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) regulate the transmission from the BLA to the CeA, which is hypothesized to play a role in the extinction of conditioned fear responses.[77] While as a whole, amygdala hyperactivity is reported by meta analysis of functional neuroimaging in PTSD, there is a large degree of heterogeniety, more so than in social anxiety disorder or phobic disorder. Comparing dorsal (roughly the CeA) and ventral(roughly the BLA) clusters, hyperactivity is more robust in the ventral cluster, while hypoactivity is evident in the dorsal cluster. The distinction may explain the blunted emotions in PTSD (via desensitization in the CeA) as well as the fear related component.[161]

In a 2007 study Vietnam War combat veterans with PTSD showed a 20% reduction in the volume of their hippocampus compared with veterans who did not have such symptoms.[162] This finding was not replicated in chronic PTSD patients traumatized at an air show plane crash in 1988 (Ramstein, Germany).[163]

Evidence suggests that endogenous cannabinoid levels are reduced in PTSD, particularly anandamide, and that cannabinoid receptors (CB1) are increased in order to compensate.[164] There appears to be a link between increased CB1 receptor availability in the amygdala and abnormal threat processing and hyperarousal, but not dysphoria, in trauma survivors.

A 2020 study found no evidence for conclusions from prior research that suggested low IQ is a risk factor for developing PTSD.[165]

Associated medical conditions

Trauma survivors often develop depression, anxiety disorders, and mood disorders in addition to PTSD.[166]

Substance use disorder, such as alcohol use disorder, commonly co-occur with PTSD.[167] Recovery from post-traumatic stress disorder or other anxiety disorders may be hindered, or the condition worsened, when substance use disorders are comorbid with PTSD. Resolving these problems can bring about improvement in an individual's mental health status and anxiety levels.[168][169]

In children and adolescents, there is a strong association between emotional regulation difficulties (e.g. mood swings, anger outbursts, temper tantrums) and post-traumatic stress symptoms, independent of age, gender, or type of trauma.[170]

Moral injury the feeling of moral distress such as a shame or guilt following a moral transgression is associated with PTSD but is distinguished from it. Moral injury is associated with shame and guilt while PTSD is associated with anxiety and fear.[171]

Prevention

Modest benefits have been seen from early access to cognitive behavioral therapy. Critical incident stress management has been suggested as a means of preventing PTSD, but subsequent studies suggest the likelihood of its producing negative outcomes.[172][173] A 2019 Cochrane review did not find any evidence to support the use of an intervention offered to everyone", and that "multiple session interventions may result in worse outcome than no intervention for some individuals."[174] The World Health Organization recommends against the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants in for acute stress (symptoms lasting less than one month).[175] Some evidence supports the use of hydrocortisone for prevention in adults, although there is limited or no evidence supporting propranolol, escitalopram, temazepam, or gabapentin.[176]

Psychological debriefing

Trauma-exposed individuals often receive treatment called psychological debriefing in an effort to prevent PTSD, which consists of interviews that are meant to allow individuals to directly confront the event and share their feelings with the counselor and to help structure their memories of the event.[177] However, several meta-analyses find that psychological debriefing is unhelpful and is potentially harmful.[177][178][179] This is true for both single-session debriefing and multiple session interventions.[174] As of 2017 the American Psychological Association assessed psychological debriefing as No Research Support/Treatment is Potentially Harmful.[180]

Risk-targeted interventions

Risk-targeted interventions are those that attempt to mitigate specific formative information or events. It can target modeling normal behaviors, instruction on a task, or giving information on the event.[181][182]

Management

Stellate ganglion block is an experimental procedure for the treatment of PTSD.[183]

Researchers are investigating a number of experimental FAAH and MAGL-inhibiting drugs of hopes of finding a better treatment for anxiety and stress-related illnesses.[184] In 2016, the FAAH-inhibitor drug BIA 10-2474 was withdrawn from human trials in France due to adverse effects.[185]

Preliminary evidence suggests that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy might be an effective treatment for PTSD.[186] However, it is important to note that the results in clinical trials of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy might be substantially influenced by expectancy effects given the unblinding of participants.[187][188] Furthermore, there is a conspicuous lack of trials comparing MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to existent first-line treatments for PTSD, such as trauma-focused psychological treatments, which seems to achieve similar or even better outcomes than MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.[189]

Psychotherapy

Trauma-focused psychotherapies for PTSD (also known as "exposure-based" or "exposure" psychotherapies), such as prolonged exposure therapy (PE), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and cognitive-reprocessing therapy (CPT) have the most evidence for efficacy and are recommended as first-line treatment for PTSD by almost all clinical practice guidelines.[190][191][192] Exposure-based psychotherapies demonstrate efficacy for PTSD caused by different trauma "types", such as combat, sexual-assault, or natural disasters.[190] At the same time, many trauma-focused psychotherapies evince high drop-out rates.[193]

Most systematic reviews and clinical guidelines indicate that psychotherapies for PTSD, most of which are trauma-focused therapies, are more effective than pharmacotherapy (medication),[194] although there are reviews that suggest exposure-based psychotherapies for PTSD and pharmacotherapy are equally effective.[195] Interpersonal psychotherapy shows preliminary evidence of probable efficacy, but more research is needed to reach definitive conclusions.[196]

Reviews of studies have found that combination therapy (psychological and pharmacotherapy) is no more effective than psychological therapy alone.[14]

Counselling

The approaches with the strongest evidence include behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies such as prolonged exposure therapy,[197] cognitive processing therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).[198][199][200] There is some evidence for brief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP), narrative exposure therapy (NET), and written exposure therapy.[201][202]

A 2019 Cochrane review evaluated couples and family therapies compared to no care and individual and group therapies for the treatment of PTSD.[203] There were too few studies on couples therapies to determine if substantive benefits were derived but preliminary RCTs suggested that couples therapies may be beneficial for reducing PTSD symptoms.[203]

A meta-analytic comparison of EMDR and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) found both protocols indistinguishable in terms of effectiveness in treating PTSD; however, "the contribution of the eye movement component in EMDR to treatment outcome" is unclear.[204] A meta-analysis in children and adolescents also found that EMDR was as efficacious as CBT.[205]

Children with PTSD are far more likely to pursue treatment at school (because of its proximity and ease) than at a free clinic.[206]

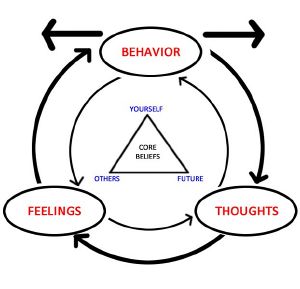

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT seeks to change the way a person feels and acts by changing the patterns of thinking or behavior, or both, responsible for negative emotions. Results from a 2018 systematic review found high strength of evidence that supports CBT-exposure therapy efficacious for a reduction in PTSD and depression symptoms, as well as the loss of PTSD diagnosis.[207] CBT has been proven to be an effective treatment for PTSD and is currently considered the standard of care for PTSD by the United States Department of Defense.[208][209] In CBT, individuals learn to identify thoughts that make them feel afraid or upset and replace them with less distressing thoughts. The goal is to understand how certain thoughts about events cause PTSD-related stress.[210][211] The provision of CBT in an Internet-based format has also been studied in a 2018 Cochrane review. This review did find similar beneficial effects for Internet-based settings as in face-to-face but the quality of the evidence was low due to the small number of trials reviewed.[212]

Exposure therapy is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy[213] that involves assisting trauma survivors to re-experience distressing trauma-related memories and reminders in order to facilitate habituation and successful emotional processing of the trauma memory. Most exposure therapy programs include both imaginal confrontation with the traumatic memories and real-life exposure to trauma reminders; this therapy modality is well supported by clinical evidence.[citation needed] The success of exposure-based therapies has raised the question of whether exposure is a necessary ingredient in the treatment of PTSD.[214] Some organizations{{ safesubst:#invoke:Unsubst||date=__DATE__ |$B=

}} have endorsed the need for exposure.[215][216] The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has been actively training mental health treatment staff in prolonged exposure therapy[217] and Cognitive Processing Therapy[218] in an effort to better treat U.S. veterans with PTSD.

Recent research on contextually based third-generation behavior therapies suggests that they may produce results comparable to some of the better validated therapies.[219] Many of these therapy methods have a significant element of exposure[220] and have demonstrated success in treating the primary problems of PTSD and co-occurring depressive symptoms.[221]

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a form of psychotherapy developed and studied by Francine Shapiro.[222] She had noticed that, when she was thinking about disturbing memories herself, her eyes were moving rapidly. When she brought her eye movements under control while thinking, the thoughts were less distressing.[222]

In 2002, Shapiro and Maxfield published a theory of why this might work, called adaptive information processing.[223] This theory proposes that eye movement can be used to facilitate emotional processing of memories, changing the person's memory to attend to more adaptive information.[224] The therapist initiates voluntary rapid eye movements while the person focuses on memories, feelings or thoughts about a particular trauma.[71][225] The therapists uses hand movements to get the person to move their eyes backward and forward, but hand-tapping or tones can also be used.[71] EMDR closely resembles cognitive behavior therapy as it combines exposure (re-visiting the traumatic event), working on cognitive processes and relaxation/self-monitoring.[71] However, exposure by way of being asked to think about the experience rather than talk about it has been highlighted as one of the more important distinguishing elements of EMDR.[226]

There have been several small controlled trials of four to eight weeks of EMDR in adults[227] as well as children and adolescents.[225] There is moderate strength of evidence to support the efficacy of EMDR "for reduction in PTSD symptoms, loss of diagnosis, and reduction in depressive symptoms" according to a 2018 systematic review update.[207] EMDR reduced PTSD symptoms enough in the short term that one in two adults no longer met the criteria for PTSD, but the number of people involved in these trials was small and thus results should be interpreted with caution pending further research.[227] There was not enough evidence to know whether or not EMDR could eliminate PTSD in adults.[227] In children and adolescents, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using MetaNSUE to avoid biases related to missing information found that EMDR was at least as efficacious as CBT, and superior to waitlist or placebo.[205] There was some evidence that EMDR might prevent depression.[227] There were no studies comparing EMDR to other psychological treatments or to medication.[227] Adverse effects were largely unstudied.[227] The benefits were greater for women with a history of sexual assault compared with people who had experienced other types of traumatizing events (such as accidents, physical assaults and war). There is a small amount of evidence that EMDR may improve re-experiencing symptoms in children and adolescents, but EMDR has not been shown to improve other PTSD symptoms, anxiety, or depression.[225]

The eye movement component of the therapy may not be critical for benefit.[71][224] As there has been no major, high quality randomized trial of EMDR with eye movements versus EMDR without eye movements, the controversy over effectiveness is likely to continue.[226] Authors of a meta-analysis published in 2013 stated, "We found that people treated with eye movement therapy had greater improvement in their symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder than people given therapy without eye movements.... Secondly we found that that in laboratory studies the evidence concludes that thinking of upsetting memories and simultaneously doing a task that facilitates eye movements reduces the vividness and distress associated with the upsetting memories."[199]

Interpersonal psychotherapy

Other approaches, in particular involving social supports,[228][229] may also be important. An open trial of interpersonal psychotherapy[230] reported high rates of remission from PTSD symptoms without using exposure.[231] A current, NIMH-funded trial in New York City is now (and into 2013) comparing interpersonal psychotherapy, prolonged exposure therapy, and relaxation therapy.[232]Template:Full citation needed[233][234]

Medication

While many medications do not have enough evidence to support their use, four Antidepressants (sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine) have been shown to have a small to modest benefit over placebo.[16] With many medications, residual PTSD symptoms following treatment is the rule rather than the exception.[235]

Benzodiazepines are not recommended for the treatment of PTSD due to a lack of evidence of benefit and risk of worsening PTSD symptoms.[236]

Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, has been used in veterans with PTSD to reduce nightmares. Studies show variability in the symptom improvement, appropriate dosages, and efficacy in this population.[237][238][55]

Cannabis is not recommended as a treatment for PTSD because scientific evidence does not currently exist demonstrating treatment efficacy for cannabinoids.[239][240] However, use of cannabis or derived products is widespread among U.S. veterans with PTSD.[241]

Other

Exercise, sport and physical activity

Physical activity can influence people's psychological[242] and physical health.[243] The U.S. National Center for PTSD recommends moderate exercise as a way to distract from disturbing emotions, build self-esteem and increase feelings of being in control again. They recommend a discussion with a doctor before starting an exercise program.[244]

Play therapy for children

Play is thought to help children link their inner thoughts with their outer world, connecting real experiences with abstract thought.[245] Repetitive play can also be one way a child relives traumatic events, and that can be a symptom of trauma in a child or young person.[246] Although it is commonly used, there have not been enough studies comparing outcomes in groups of children receiving and not receiving play therapy, so the effects of play therapy are not yet understood.[71][245]

Military programs

Many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have faced significant physical, emotional, and relational disruptions. In response, the United States Marine Corps has instituted programs to assist them in re-adjusting to civilian life, especially in their relationships with spouses and loved ones, to help them communicate better and understand what the other has gone through.[247] Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) developed the Battlemind program to assist service members avoid or ameliorate PTSD and related problems. Wounded Warrior Project partnered with the US Department of Veterans Affairs to create Warrior Care Network, a national health system of PTSD treatment centers.[248][249]

Symptoms

Children and adolescents

The diagnosis of PTSD was originally developed for adults who had suffered from a single-event trauma, such as rape, or a traumatic experience during a war.[250] However, the situation for many children is quite different. Children can suffer chronic trauma such as maltreatment, family violence, dysfunction, or a disruption in attachment to their primary caregiver.[251] In many cases, it is the child's caregiver who causes the trauma.[250] The diagnosis of PTSD does not take into account how the developmental stages of children may affect their symptoms and how trauma can affect a child's development.[250]

The term developmental trauma disorder (DTD) has been proposed as the childhood equivalent of C-PTSD.[251] This developmental form of trauma places children at risk for developing psychiatric and medical disorders.[251] Bessel van der Kolk explains DTD as numerous encounters with interpersonal trauma such as physical assault, sexual assault, violence or death. It can also be brought on by subjective events such as abandonment, betrayal, defeat or shame.[90]

Repeated traumatization during childhood leads to symptoms that differ from those described for PTSD.[90] Cook and others describe symptoms and behavioural characteristics in seven domains:[252][42]

- Attachment – "problems with relationship boundaries, lack of trust, social isolation, difficulty perceiving and responding to others' emotional states"

- Biology – "sensory-motor developmental dysfunction, sensory-integration difficulties, somatization, and increased medical problems"

- Affect or emotional regulation – "poor affect regulation, difficulty identifying and expressing emotions and internal states, and difficulties communicating needs, wants, and wishes"

- Dissociation – "amnesia, depersonalization, discrete states of consciousness with discrete memories, affect, and functioning, and impaired memory for state-based events"

- Behavioural control – "problems with impulse control, aggression, pathological self-soothing, and sleep problems"

- Cognition – "difficulty regulating attention; problems with a variety of 'executive functions' such as planning, judgement, initiation, use of materials, and self-monitoring; difficulty processing new information; difficulty focusing and completing tasks; poor object constancy; problems with 'cause-effect' thinking; and language developmental problems such as a gap between receptive and expressive communication abilities."

- Self-concept – "fragmented and disconnected autobiographical narrative, disturbed body image, low self-esteem, excessive shame, and negative internal working models of self".

Adults

Adults with C-PTSD have sometimes experienced prolonged interpersonal traumatization beginning in childhood, rather than, or as well as, in adulthood. These early injuries interrupt the development of a robust sense of self and of others. Because physical and emotional pain or neglect was often inflicted by attachment figures such as caregivers or older siblings, these individuals may develop a sense that they are fundamentally flawed and that others cannot be relied upon.[53][253] This can become a pervasive way of relating to others in adult life, described as insecure attachment. This symptom is neither included in the diagnosis of dissociative disorder nor in that of PTSD in the current DSM-5 (2013). Individuals with Complex PTSD also demonstrate lasting personality disturbances with a significant risk of revictimization.[254]

Six clusters of symptoms have been suggested for diagnosis of C-PTSD:[255][256]

- Alterations in regulation of affect and impulses

- Alterations in attention or consciousness

- Alterations in self-perception

- Alterations in relations with others

- Somatization

- Alterations in systems of meaning[256]

Experiences in these areas may include:[44][257]

- Changes in emotional regulation, including experiences such as persistent dysphoria, chronic suicidal preoccupation, self-injury, explosive or extremely inhibited anger (may alternate), and compulsive or extremely inhibited sexuality (may alternate).

- Variations in consciousness, such as amnesia or improved recall for traumatic events, episodes of dissociation, depersonalization/derealization, and reliving experiences (either in the form of intrusive PTSD symptoms or in ruminative preoccupation).

- Changes in self-perception, such as a sense of helplessness or paralysis of initiative, shame, guilt and self-blame, a sense of defilement or stigma, and a sense of being completely different from other human beings (may include a sense of specialness, utter aloneness, a belief that no other person can understand, or a feeling of nonhuman identity).

- Varied changes in perception of the perpetrators, such as a preoccupation with the relationship with a perpetrator (including a preoccupation with revenge), an unrealistic attribution of total power to a perpetrator (though the individual's assessment may be more realistic than the clinician's), idealization or paradoxical gratitude, a sense of a special or supernatural relationship with a perpetrator, and acceptance of a perpetrator's belief system or rationalizations.

- Alterations in relations with others, such as isolation and withdrawal, disruption in intimate relationships, a repeated search for a rescuer (may alternate with isolation and withdrawal), persistent distrust, and repeated failures of self-protection.

- Changes in systems of meaning, such as a loss of sustaining faith and a sense of hopelessness and despair.

Diagnostics

C-PTSD was considered for inclusion in the DSM-IV but was not included when the DSM-IV was published in 1994.[44] It was also not included in the DSM-5, though post-traumatic stress disorder continues to be listed as a disorder.[258]

Differential diagnosis

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was included in the DSM-III (1980), mainly due to the relatively large numbers of American combat veterans of the Vietnam War who were seeking treatment for the lingering effects of combat stress. In the 1980s, various researchers and clinicians suggested that PTSD might also accurately describe the sequelae of such traumas as child sexual abuse and domestic abuse.[259] However, it was soon suggested that PTSD failed to account for the cluster of symptoms that were often observed in cases of prolonged abuse, particularly that which was perpetrated against children by caregivers during multiple childhood and adolescent developmental stages. Such patients were often extremely difficult to treat with established methods.[259]

PTSD descriptions fail to capture some of the core characteristics of C-PTSD. These elements include captivity, psychological fragmentation, the loss of a sense of safety, trust, and self-worth, as well as the tendency to be revictimized. Most importantly, there is a loss of a coherent sense of self: this loss, and the ensuing symptom profile, most pointedly differentiates C-PTSD from PTSD.[44]

Complex PTSD embraces a wider range of symptoms relative to PTSD, specifically emphasizing problems of emotional regulation, negative self-concept, and interpersonal problems. Diagnosing complex PTSD can imply that this wider range of symptoms is caused by traumatic experiences, rather than acknowledging any pre-existing experiences of trauma which could lead to a higher risk of experiencing future traumas. It also asserts that this wider range of symptoms and higher risk of traumatization are related by hidden confounder variables and there is no causal relationship between symptoms and trauma experiences.[260] In the diagnosis of PTSD, the definition of the stressor event is narrowly limited to life-threatening events, with the implication that these are typically sudden and unexpected events. Complex PTSD vastly widened the definition of potential stressor events by calling them adverse events, and deliberating dropping reference to life-threatening, so that experiences can be included such as neglect, emotional abuse, or living in a war zone without having specifically experienced life-threatening events.[52] By broadening the stressor criterion, an article published by the Child and Youth Care Forum claims this has led to confusing differences between competing definitions of complex PTSD, undercutting the clear operationalization of symptoms seen as one of the successes of the DSM.[261]

C-PTSD is also characterized by attachment disorder, particularly the pervasive insecure, or disorganized-type attachment.[262] DSM-IV (1994) dissociative disorders and PTSD do not include insecure attachment in their criteria. As a consequence of this aspect of C-PTSD, when some adults with C-PTSD become parents and confront their own children's attachment needs, they may have particular difficulty in responding sensitively especially to their infants' and young children's routine distress – such as during routine separations, despite these parents' best intentions and efforts.[263] Although the great majority of survivors do not abuse others,[264] this difficulty in parenting may have adverse repercussions for their children's social and emotional development if parents with this condition and their children do not receive appropriate treatment.[265][266]

Thus, a differentiation between the diagnostic category of C-PTSD and that of PTSD has been suggested. C-PTSD better describes the pervasive negative impact of chronic repetitive trauma than does PTSD alone.[257] PTSD can exist alongside C-PTSD, however a sole diagnosis of PTSD often does not sufficiently encapsulate the breadth of symptoms experienced by those who have experienced prolonged traumatic experience, and therefore C-PTSD extends beyond the PTSD parameters.[53]

C-PTSD also differs from continuous traumatic stress disorder (CTSD), which was introduced into the trauma literature by Gill Straker (1987).[267] It was originally used by South African clinicians to describe the effects of exposure to frequent, high levels of violence usually associated with civil conflict and political repression. The term is also applicable to the effects of exposure to contexts in which gang violence and crime are endemic as well as to the effects of ongoing exposure to life threats in high-risk occupations such as police, fire and emergency services.

Traumatic grief

Traumatic grief[268][269][270][271] or complicated mourning[272] are conditions[273] where both trauma and grief coincide. There are conceptual links between trauma and bereavement since loss of a loved one is inherently traumatic.[274] If a traumatic event was life-threatening, but did not result in a death, then it is more likely that the survivor will experience post-traumatic stress symptoms. If a person dies, and the survivor was close to the person who died, then it is more likely that symptoms of grief will also develop. When the death is of a loved one, and was sudden or violent, then both symptoms often coincide. This is likely in children exposed to community violence.[275][276]

For C-PTSD to manifest traumatic grief, the violence would occur under conditions of captivity, loss of control and disempowerment, coinciding with the death of a friend or loved one in life-threatening circumstances. This again is most likely for children and stepchildren who experience prolonged domestic or chronic community violence that ultimately results in the death of friends and loved ones. The phenomenon of the increased risk of violence and death of stepchildren is referred to as the Cinderella effect.

Borderline personality disorder

C-PTSD may share some symptoms with both PTSD and borderline personality disorder (BPD).[277] However, there is enough evidence to also differentiate C-PTSD from borderline personality disorder.

It may help to understand the intersection of attachment theory with C-PTSD and BPD if one reads the following opinion of Bessel A. van der Kolk together with an understanding drawn from a description of BPD:

Uncontrollable disruptions or distortions of attachment bonds precede the development of post-traumatic stress syndromes. People seek increased attachment in the face of danger. Adults, as well as children, may develop strong emotional ties with people who intermittently harass, beat, and, threaten them. The persistence of these attachment bonds leads to confusion of pain and love. Trauma can be repeated on behavioural, emotional, physiologic, and neuroendocrinologic levels. Repetition on these different levels causes a large variety of individual and social suffering.

However, C-PTSD and BPD have been found by some researchers to be distinctive disorders with different features. Those with C-PTSD do not fear abandonment or have unstable patterns of relations; rather, they withdraw. There are distinct and notably large differences between BPD and C-PTSD and while there are some similarities – predominantly in terms of issues with attachment (though this plays out in different ways) and trouble regulating strong emotional affects – the disorders are different in nature[citation needed].

While the individuals in the BPD reported many of the symptoms of PTSD and CPTSD, the BPD class was clearly distinct in its endorsement of symptoms unique to BPD. The RR ratios presented in Table 5 revealed that the following symptoms were highly indicative of placement in the BPD rather than the CPTSD class: (1) frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment, (2) unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation, (3) markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self, and (4) impulsiveness. Given the gravity of suicidal and self-injurious behaviors, it is important to note that there were also marked differences in the presence of suicidal and self-injurious behaviors with approximately 50% of individuals in the BPD class reporting this symptom but much fewer and an equivalent number doing so in the CPTSD and PTSD classes (14.3 and 16.7%, respectively). The only BPD symptom that individuals in the BPD class did not differ from the CPTSD class was chronic feelings of emptiness, suggesting that in this sample, this symptom is not specific to either BPD or CPTSD and does not discriminate between them.

Overall, the findings indicate that there are several ways in which complex PTSD and BPD differ, consistent with the proposed diagnostic formulation of CPTSD. BPD is characterized by fears of abandonment, unstable sense of self, unstable relationships with others, and impulsive and self-harming behaviors. In contrast, in CPTSD as in PTSD, there was little endorsement of items related to instability in self-representation or relationships. Self-concept is likely to be consistently negative and relational difficulties concern mostly avoidance of relationships and sense of alienation.[278]

In addition, 25% of those diagnosed with BPD have no known history of childhood neglect or abuse and individuals are six times as likely to develop BPD if they have a relative who was so diagnosed[citation needed] compared to those who do not. One conclusion is that there is a genetic predisposition to BPD unrelated to trauma. Researchers conducting a longitudinal investigation of identical twins found that "genetic factors play a major role in individual differences of borderline personality disorder features in Western society."[279] A 2014 study published in European Journal of Psychotraumatology was able to compare and contrast C-PTSD, PTSD, Borderline Personality Disorder and found that it could distinguish between individual cases of each and when it was co-morbid, arguing for a case of separate diagnoses for each.[278] BPD may be confused with C-PTSD by some without proper knowledge of the two conditions because those with BPD also tend to have PTSD or to have some history of trauma.

In Trauma and Recovery, Herman expresses the additional concern that patients with C-PTSD frequently risk being misunderstood as inherently 'dependent', 'masochistic', or 'self-defeating', comparing this attitude to the historical misdiagnosis of female hysteria.[44] However, those who develop C-PTSD do so as a result of the intensity of the traumatic bond – in which someone becomes tightly biolo-chemically bound to someone who abuses them and the responses they learned to survive, navigate and deal with the abuse they suffered then become automatic responses, imbedded in their personality over the years of trauma – a normal reaction to an abnormal situation.[280]

Treatment

While standard evidence-based treatments may be effective for treating post traumatic stress disorder, treating complex PTSD often involves addressing interpersonal relational difficulties and a different set of symptoms which make it more challenging to treat. According to the United States Department of Veteran Affairs:

The current PTSD diagnosis often does not fully capture the severe psychological harm that occurs with prolonged, repeated trauma. People who experience chronic trauma often report additional symptoms alongside formal PTSD symptoms, such as changes in their self-concept and the way they adapt to stressful events.[281]

The utility of PTSD-derived psychotherapies for assisting children with C-PTSD is uncertain. This area of diagnosis and treatment calls for caution in use of the category C-PTSD. Dr. Julian Ford and Dr. Bessel van der Kolk have suggested that C-PTSD may not be as useful a category for diagnosis and treatment of children as a proposed category of developmental trauma disorder (DTD).[282] According to Courtois & Ford, for DTD to be diagnosed it requires a

history of exposure to early life developmentally adverse interpersonal trauma such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, violence, traumatic losses or other significant disruption or betrayal of the child's relationships with primary caregivers, which has been postulated as an etiological basis for complex traumatic stress disorders. Diagnosis, treatment planning and outcome are always relational.[282]

Since C-PTSD or DTD in children is often caused by chronic maltreatment, neglect or abuse in a care-giving relationship the first element of the biopsychosocial system to address is that relationship. This invariably involves some sort of child protection agency. This both widens the range of support that can be given to the child but also the complexity of the situation, since the agency's statutory legal obligations may then need to be enforced.

A number of practical, therapeutic and ethical principles for assessment and intervention have been developed and explored in the field:[282]

- Identifying and addressing threats to the child's or family's safety and stability are the first priority.

- A relational bridge must be developed to engage, retain and maximize the benefit for the child and caregiver.

- Diagnosis, treatment planning and outcome monitoring are always relational (and) strengths based.

- All phases of treatment should aim to enhance self-regulation competencies.

- Determining with whom, when and how to address traumatic memories.

- Preventing and managing relational discontinuities and psychosocial crises.

Adults

Trauma recovery model

Judith Lewis Herman, in her book, Trauma and Recovery, proposed a complex trauma recovery model that occurs in three stages:

- Establishing safety

- Remembrance and mourning for what was lost

- Reconnecting with community and more broadly, society

Herman believes recovery can only occur within a healing relationship and only if the survivor is empowered by that relationship. This healing relationship need not be romantic or sexual in the colloquial sense of "relationship", however, and can also include relationships with friends, co-workers, one's relatives or children, and the therapeutic relationship.[44]

Complex trauma means complex reactions and this leads to complex treatments. [citation needed] Hence, treatment for C-PTSD requires a multi-modal approach.[42]

It has been suggested that treatment for complex PTSD should differ from treatment for PTSD by focusing on problems that cause more functional impairment than the PTSD symptoms. These problems include emotional dysregulation, dissociation, and interpersonal problems.[262] Six suggested core components of complex trauma treatment include:[42]

- Safety

- Self-regulation

- Self-reflective information processing

- Traumatic experiences integration

- Relational engagement

- Positive affect enhancement

The above components can be conceptualized as a model with three phases. Every case will not be the same, but one can expect the first phase to consist of teaching adequate coping strategies and addressing safety concerns. The next phase would focus on decreasing avoidance of traumatic stimuli and applying coping skills learned in phase one. The care provider may also begin challenging assumptions about the trauma and introducing alternative narratives about the trauma. The final phase would consist of solidifying what has previously been learned and transferring these strategies to future stressful events.[283]

Neuroscientific and trauma informed interventions

In practice, the forms of treatment and intervention varies from individual to individual since there is a wide spectrum of childhood experiences of developmental trauma and symptomatology and not all survivors respond positively, uniformly, to the same treatment. Therefore, treatment is generally tailored to the individual.[284] Recent neuroscientific research has shed some light on the impact that severe childhood abuse and neglect (trauma) has on a child's developing brain, specifically as it relates to the development in brain structures, function and connectivity among children from infancy to adulthood. This understanding of the neurophysiological underpinning of complex trauma phenomena is what currently is referred to in the field of traumatology as 'trauma informed' which has become the rationale which has influenced the development of new treatments specifically targeting those with childhood developmental trauma.[285][286] Dr. Martin Teicher, a Harvard psychiatrist and researcher, has suggested that the development of specific complex trauma related symptomatology (and in fact the development of many adult onset psychopathologies) may be connected to gender differences and at what stage of childhood development trauma, abuse or neglect occurred.[285] For example, it is well established that the development of dissociative identity disorder among women is often associated with early childhood sexual abuse.

Use of evidence-based treatment and its limitations

One of the current challenges faced by many survivors of complex trauma (or developmental trauma disorder) is support for treatment since many of the current therapies are relatively expensive and not all forms of therapy or intervention are reimbursed by insurance companies who use evidence-based practice as a criteria for reimbursement. Cognitive behavioral therapy, prolonged exposure therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy are well established forms of evidence-based intervention. These treatments are approved and endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association and the Veteran's Administration.

While standard evidence-based treatments may be effective for treating standard post-traumatic stress disorder, treating complex PTSD often involves addressing interpersonal relational difficulties and a different set of symptoms which make it more challenging to treat. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs acknowledges,

the current PTSD diagnosis often does not fully capture the severe psychological harm that occurs with prolonged, repeated trauma. People who experience chronic trauma often report additional symptoms alongside formal PTSD symptoms, such as changes in their self-concept and the way they adapt to stressful events.[287]

For example, "Limited evidence suggests that predominantly [Cognitive behavioral therapy] CBT [evidence-based] treatments are effective, but do not suffice to achieve satisfactory end states, especially in Complex PTSD populations."[288]

Treatment challenges

It is widely acknowledged by those who work in the trauma field that there is no one single, standard, 'one size fits all' treatment for complex PTSD.[citation needed] There is also no clear consensus regarding the best treatment among the greater mental health professional community which included clinical psychologists, social workers, licensed therapists MFTs) and psychiatrists. Although most trauma neuroscientifically informed practitioners understand the importance of utilizing a combination of both 'top down' and 'bottom up' interventions as well as including somatic interventions (sensorimotor psychotherapy or somatic experiencing or yoga) for the purposes of processing and integrating trauma memories.

Survivors with complex trauma often struggle to find a mental health professional who is properly trained in trauma informed practices. They can also be challenging to receive adequate treatment and services to treat a mental health condition which is not universally recognized or well understood by general practitioners.

Allistair and Hull echo the sentiment of many other trauma neuroscience researchers (including Bessel van der Kolk and Bruce D. Perry) who argue:

Complex presentations are often excluded from studies because they do not fit neatly into the simple nosological categorisations required for research power. This means that the most severe disorders are not studied adequately and patients most affected by early trauma are often not recognised by services. Both historically and currently, at the individual as well as the societal level, "dissociation from the acknowledgement of the severe impact of childhood abuse on the developing brain leads to inadequate provision of services. Assimilation into treatment models of the emerging affective neuroscience of adverse experience could help to redress the balance by shifting the focus from top-down regulation to bottom-up, body-based processing."[289]