Albatross

| Albatross | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus)

| ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Diomedea |

Albatrosses are large seabirds in the biological family Diomedeidae of the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and the great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) have the largest wingspans of any extant (living) birds. They are closely related to the procellariids, storm-petrels, and diving-petrels, all of which also are part of the Procellariiformes. Some systematists recognize another order, Ciconiiformes, instead of Procellariiformes (see Taxonomy and evolution)

Albatrosses range widely in the Southern Ocean (South Pole Ocean or Antarctic Ocean) and the North Pacific Ocean. They are generally absent from the North Atlantic Ocean, although fossil remains show they once occurred there too and occasional vagrants are encountered.

Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the most part on remote oceanic islands, often with several species nesting together. Pair bonds between males and females form over several years, with the use of ritualized dances, and will last for the life of the pair. A breeding season can take over a year from laying to fledging, with a single egg laid in each breeding attempt.

Albatrosses are highly efficient in the air, using dynamic soaring and slope soaring to cover great distances with little exertion. They feed on squid, fish, and krill by either scavenging, surface seizing, or diving.

The albatrosses are usually regarded as falling into four genera, but there is disagreement over the number of species. The four genera are the great albatrosses (Diomedea), the mollymawks (Thalassarche), the North Pacific albatrosses (Phoebastria), and the sooty albatrosses or sooties (Phoebetria).

Of the 21 species of albatrosses recognized by the IUCN, 19 are threatened with extinction. Numbers of albatrosses have declined in the past due to harvesting for feathers, but today the albatrosses are threatened by introduced species such as rats and feral cats that attack eggs, chicks and nesting adults; by pollution; by a serious decline in fish stocks in many regions largely due to overfishing; and by long-line fishing. Long-line fisheries pose the greatest threat, as feeding birds are attracted to the bait and become hooked on the lines and drown. Governments, conservation organizations and fishermen are all working towards reducing this by-catch.

Albatross biology

Morphology and flight

The albatrosses are a group of large to very large birds; they are the largest of the procellariiformes.

The bill (beak) is large, strong and sharp-edged, the upper mandible terminating in a large hook. This bill is composed of several horny plates, and along the sides are the two "tubes," long nostrils that give the order its name. These tubes allow the albatrosses to have an acute sense of smell, an unusual ability for birds. Like other Procellariiformes, they use this olfactory ability while foraging in order to locate potential food sources (Lequette et al. 1989). The tubes of all albatrosses are along the sides of the bill, unlike the rest of the Procellariiformes where the tubes run along the top of the bill.

The feet have no hind toe and the three anterior toes are completely webbed. The legs are strong for Procellariiformes, in fact, almost unique among the order in that they and the giant petrels are able to walk well on land.

The adult plumage of most of the albatrosses is usually some variation of dark upper-wing and back, white undersides, often compared to that of a gull. Of these, the species range from the Southern Royal Albatross which is almost completely white except for the ends and trailing edges of the wings in fully mature males, to the Amsterdam Albatross which has an almost juvenile-like breeding plumage with a great deal of brown, particularly a strong brown band around the chest. Several species of mollymawks and North Pacific albatrosses have face markings like eye patches, or have gray or yellow on the head and nape. Three albatross species, the Black-footed Albatross and the two sooty albatrosses, vary completely from the usual patterns and are almost entirely dark brown (or dark gray in places in the case of the Light-mantled Sooty Albatross). Albatrosses take several years to get their full adult breeding plumage.

The wingspans of the largest great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) are the greatest of any bird, exceeding 340 cm (over 11 feet), although the other species' wingspans are considerably smaller. The wings are stiff and cambered, with thickened streamlined leading edges.

Albatrosses travel huge distances with two techniques used by many long-winged seabirds, dynamic soaring and slope soaring. Dynamic soaring enables them to minimize the effort needed by gliding across wave fronts gaining energy from the vertical wind gradient. Slope soaring is more straightforward: the albatross turns to the wind, gaining height, from where it can then glide back down to the sea. Albatross have high glide ratios, around 1:22 to 1:23, meaning that for every meter they drop, they can travel forward 22 meters. They are aided in soaring by a shoulder-lock, a sheet of tendon that locks the wing when fully extended, allowing the wing to be kept up and out without any muscle expenditure, a morphological adaptation they share with the giant petrels (Pennycuick 1982). Albatrosses combine these soaring techniques with the use of predictable weather systems; albatrosses in the southern hemisphere flying north from their colonies will take a clockwise route, and those flying south will fly counterclockwise (Tickell 2000).

Albatrosses are so well adapted to this lifestyle that their heart rates while flying are close to their basal heart rate when resting. This efficiency is such that the most energetically demanding aspect of a foraging trip is not the distance covered, but the landings, take-offs and hunting they undertake having found a food source (Weimerskirch et al. 2000). This efficient, long-distance traveling underlies the albatross's success as a long-distance forager, covering great distances and expending little energy looking for patchily distributed food sources.

Their adaptation to gliding flight makes them dependent on wind and waves, however, as their long wings are ill-suited to powered flight and most species lack the muscles and energy to undertake sustained flapping flight. Albatrosses in calm seas are forced to rest on the ocean's surface until the wind picks up again. They also sleep while resting on the surface (and not while on the wing as is sometimes thought). The North Pacific albatrosses can use a flight style known as flap-gliding, where the bird progresses by bursts of flapping followed by gliding (Warham 1996). When taking off, albatrosses need to take a run up to allow enough air to move under the wing to provide lift.

Distribution and range at sea

Most albatrosses range in the southern hemisphere from Antarctica to Australia, South Africa, and South America. The exceptions to this are the four North Pacific albatrosses, of which three occur exclusively in the North Pacific, from Hawaii to Japan, Alaska, and California; and one, the Waved Albatross, breeds in the Galapagos Islands and feeds off the coast of South America. The need for wind in order to glide is the reason albatrosses are for the most part confined to higher latitudes; being unsuited to sustained flapping flight makes crossing the doldrums extremely difficult. The exception, the Waved Albatross, is able to live in the equatorial waters around the Galapagos Islands because of the cool waters of the Humboldt Current and the resulting winds.

It is not known for certain why the albatrosses became extinct in the North Atlantic, although rising sea levels due to an interglacial warming period are thought to have submerged the site of a Short-tailed Albatross colony that has been excavated in Bermuda (Olson and Hearty 2003). Some southern species have occasionally turned up as vagrants in the North Atlantic and can become exiled, remaining there for decades. One of these exiles, a Black-browed Albatross, returned to Northern Gannet (a seabird) colonies in Scotland for many years in a lonely attempt to breed (Cocker and Mabey 2005).

The use of satellite tracking is teaching scientists a great deal about the way albatrosses forage across the ocean in order to find food. They undertake no annual migration, but disperse widely after breeding, in the case of southern hemisphere species, often undertaking circumpolar trips (Croxall et al. 2005). There is also evidence that there is separation of the ranges of different species at sea. A comparison of the foraging niches of two related species that breed on Campbell Island, the Campbell Albatross and the Grey-headed Albatross, showed the Campbell Albatross primarily fed over the Campbell Plateau whereas the Grey-Headed Albatross fed in more pelagic, oceanic waters. Wandering Albatrosses also react strongly to bathymetry, feeding only in waters deeper than 1000 m (3281 feet); so rigidly did the satellite plots match this contour that one scientist remarked, "It almost appears as if the birds notice and obey a 'No Entry' sign where the water shallows to less than 1000 m" (Brooke 2004). There is also evidence of different ranges for the two sexes of the same species; a study of Tristan Albatrosses breeding on Gough Island showed that males foraged to the west of Gough and females to the east.

Albatrosses are colonial, usually nesting on isolated islands. Where colonies are on larger landmasses, they are found on exposed headlands with good approaches from the sea in several directions, like the colony on the Otago Peninsula in Dunedin, New Zealand. Colonies vary from the very dense aggregations favored by the mollymawks (Black-browed Albatross colonies on the Falkland Islands have densities of 70 nests per 100 m²) to the much looser groups and widely spaced individual nests favored by the sooty and great albatrosses. All albatross colonies are on islands that historically were free of land mammals.

Diet

The albatross diet is dominated by cephalopods, fish, and crustaceans (such as krill), although they will also scavenge carrion (carcasses of a dead animal) and feed on other zooplankton beyond krill (Tickell 2000). It should be noted that for most species, a comprehensive understanding of diet is only known for the breeding season, when the albatrosses regularly return to land and study is possible. The importance of each of these food sources varies from species to species, and even from population to population; some concentrate on squid alone, others take more krill or fish. Of the two albatross species found in Hawaii, one, the Black-footed Albatross, takes mostly fish while the Laysan feeds on squid.

The use of dataloggers at sea that record ingestion of water against time (providing a likely time of feeding) suggest that albatross predominantly feed during the day. Analysis of the squid beaks regurgitated by albatrosses has shown that many of the squid eaten are too large to have been caught alive (Croxall and Prince 1994) and include mid-water species likely to be beyond the reach of albatross, suggesting that, for some species (like the Wandering Albatross), scavenged squid may be an important part of the diet. The source of these dead squid is a matter of debate; some certainly comes from squid fisheries, but in nature it primarily comes from the die-off that occurs after squid spawning and the vomit of squid-eating whales (sperm whales, pilot whales and Southern Bottlenose Whales). The diet of other species, like the Black-browed Albatross or the Grey-headed Albatross, is rich with smaller species of squid that tend to sink after death, and scavenging is not assumed to play a large role in their diet.

Until recently, it was thought that albatross were predominantly surface feeders, swimming at the surface and snapping up squid and fish pushed to the surface by currents, predators, or death. The deployment of capillary depth recorders, which record the maximum dive depth undertaken by a bird (between attaching it to a bird and recovering it when it returns to land), has shown that while some species, like the Wandering Albatross, do not dive deeper than a meter, some species, like the Light-mantled Sooty Albatross, have a mean diving depth of almost 5 m and can dive as deep as 12.5 m (Prince et al. 1994). In addition to surface feeding and diving, they have now also been observed plunge diving from the air to snatch prey (Cobley 1996).

Breeding

Albatrosses are highly philopatric, meaning they will usually return to their natal colony to breed. This tendency to return is so strong that a study of Laysan Albatross showed that the average distance between hatching site and the site where a bird established its own territory was 22 meters (Fisher 1976).

Like most seabirds, albatrosses are K-selected (rather than R-selected) with regard to their life history, meaning they live much longer than other birds, they delay breeding for longer, and invest more effort into fewer young. Albatrosses are very long lived; most species survive upwards of 50 years, the oldest recorded being a Northern Royal Albatross that was ringed as an adult and survived for another 51 years, giving it an estimated age of 61 (Robertson 1993). Given that most albatross ringing projects are considerably younger than that, it is thought likely that other species will prove to live that long and even longer.

Albatrosses reach sexual maturity after about five years, but even once they have reached maturity, they will not begin to breed for another couple of years (even up to ten years for some species). Young non-breeders will attend a colony prior to beginning to breed, spending many years practicing the elaborate breeding rituals and "dances" for which the family is famous (Jouventin et al. 1981). Birds arriving back at the colony for the first time already have the stereotyped behaviors that compose albatross language, but can neither "read" that behavior as exhibited by other birds nor respond appropriately (Tickle 2000). After a period of trial and error learning, the young birds learn the syntax and perfect the dances. This language is mastered more rapidly if the younger birds are around older birds.

The repertoire of mating behavior involves synchronized performances of various actions such as preening, pointing, calling, bill clacking, staring, and combinations of such behaviors (like the sky-call) (Pickering and Barrow 2001). When a bird first returns to the colony, it will dance with many partners, but after a number of years the number of birds an individual will interact with drops, until one partner is chosen and a pair is formed. They then continue to perfect an individual language that will eventually be unique to that one pair. Having established a pair bond that will last for life, however, most of that dance will never be used ever again.

Albatrosses are thought to undertake these elaborate and painstaking rituals to ensure that the correct partner has been chosen and to perfect recognition of their partner, as egg laying and chick rearing is a huge investment. Even species that can complete an egg-laying cycle in under a year seldom lay eggs in consecutive years (Brooke 2004). The great albatrosses (like the Wandering Albatross) take over a year to raise a chick from laying to fledging. Albatrosses lay a single egg in a breeding season; if the egg is lost to predators or accidentally broken, then no further breeding attempts are made that year. The "divorce" of a pair is a rare occurrence, usually only happening after several years of breeding failure.

All the southern albatrosses create large nests for their egg, whereas the three species in the north Pacific make more rudimentary nests. The Waved Albatross, on the other hand, makes no nest and will even move its egg around the pair's territory, as much as 50 m, sometimes causing it to lose the egg (Anderson and Cruz 1998). In all albatross species, both parents incubate the egg in stints that last between one day and three weeks. Incubation lasts around 70 to 80 days (longer for the larger albatrosses), the longest incubation period of any bird. It can be an energetically demanding process, with the adult losing as much as 83 g of body weight a day (Warham 1990).

After hatching, the chick is brooded and guarded for three weeks until it is large enough to defend and thermoregulate itself. During this period, the parents feed the chick small meals when they relieve each other from duty. After the brooding period is over, the chick is fed in regular intervals by both parents. The parents adopt alternative patterns of short and long foraging trips, providing meals that weigh around 12 percent of their body weight (around 600 g). The meals are composed of both fresh squid, fish, and krill, as well as stomach oil, an energy-rich food that is lighter to carry than undigested prey items (Warham 1976). This oil is created in a stomach organ known as a proventriculus from digested prey items by most tubenoses, and gives them their distinctive musty smell.

Albatross chicks take a long time to fledge. In the case of the great albatrosses, it can take up to 280 days; even for the smaller albatrosses, it takes anywhere between 140 and 170 days (Carboneras 1992). Like many seabirds, albatross chicks will gain enough weight to be heavier than their parents, and prior to fledging they use these reserves to build up body condition (particularly growing all their flight feathers), usually fledging at the same weight as their parents. Albatross chicks fledge on their own and receive no further help from their parents, who return to the nest after fledging, unaware their chick has left. Studies of juveniles dispersing at sea have suggested an innate migration behavior, a genetically coded navigation route, which helps young birds when they are first out at sea (Åkesson and Weimerskirch 2005).

Etymology

The name albatross is derived from the Arabic al-câdous or al-ġaţţās (a pelican; literally, "the diver"), which traveled to English via the Portuguese form alcatraz ("gannet"), which is also the origin of the title of the former U.S. prison, Alcatraz. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that the word alcatraz was originally applied to the frigatebird; the modification to albatross was perhaps influenced by Latin albus, meaning "white," in contrast to frigatebirds, which are black (Tickell 2000). The Portuguese word albatroz is of English origin.

They were once commonly known as Goonie birds or Gooney birds, particularly those of the North Pacific. In the southern hemisphere, the name mollymawk is still well established in some areas, which is a corrupted form of malle-mugge, an old Dutch name for the Northern Fulmar. The name Diomedea, assigned to the albatrosses by Linnaeus, references the mythical metamorphosis of the companions of the Greek warrior Diomedes into birds.

Albatrosses and humans

Albatrosses and culture

Albatrosses have been described as "the most legendary of all birds" (Carboneras 1992). An albatross is a central emblem in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; a captive albatross is also a metaphor for the poète maudit in a poem of Charles Baudelaire. It is from the former poem that the usage of albatross as a metaphor is derived; someone with a burden or obstacle is said to have 'an albatross around their neck', the punishment given in the poem to the mariner who killed the albatross. In part due to the poem, there is a widespread myth that sailors believe it disastrous to shoot or harm an albatross; in truth, however, sailors regularly killed and ate them (Cocker and Mabey 2005), but they were often regarded as the souls of lost sailors.

Albatrosses are popular birds for birdwatchers and their colonies popular destinations for ecotourists. Regular birdwatching trips are taken out of many coastal towns and cities, like Monterey and Wollongong in New South Wales, Kaikoura in New Zealand, and Sydney in Australia, where pelagic seabirds and albatrosses are easily attracted to these sightseeing boats by the deployment of fish oil into the sea. Visits to colonies can be very popular; the Northern Royal Albatross colony at Taiaroa Head in New Zealand attracts 40,000 visitors a year (Brooke 2004), and more isolated colonies are regular attractions on cruises to sub-Antarctic islands.

Threats and conservation

In spite of often being accorded legendary status, albatrosses have not escaped either indirect or direct pressure from humans. Early encounters with albatrosses by Polynesians and Aleut Indians resulted in hunting and in some cases extirpation from some islands (such as Easter Island). As Europeans began sailing the world, they too began to hunt albatross, "fishing" for them from boats to serve at the table or blasting them for sport (Safina 2002). This sport reached its peak on emigration lines bound for Australia, and only died down when ships became too fast to fish from, and regulations stopped the discharge of weapons for safety reasons. In the nineteenth century, albatross colonies, particularly those in the North Pacific, were harvested for the feather trade, leading to the near extinction of the Short-tailed Albatross.

Of the 21 albatross species recognised by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) on their IUCN Red List, 19 are threatened, and the other two are near threatened (IUCN 2004). Two species (as recognized by the IUCN) are considered critically endangered: the Amsterdam Albatross and the Chatham Albatross. One of the main threats is commercial long-line fishing (Brothers 1991), as the albatrosses and other seabirds, which will readily feed on offal (internal organs used as bait), are attracted to the set bait, become hooked on the lines, and drown. An estimated 100,000 albatross per year are killed in this fashion. Unregulated pirate (illegal) fisheries exacerbate the problem.

Another threat to albatrosses is introduced species, such as rats or feral cats, which directly attack the albatross or its chicks and eggs. Albatrosses have evolved to breed on islands where land mammals are absent and have not evolved defences against them. Even species as small as mice can be detrimental; on Gough Island the chicks of Tristan Albatrosses are attacked and eaten alive by introduced house mice that are almost 300 times smaller than they are (BBC 2005). Introduced species can have other indirect effects: cattle overgrazed essential cover on Amsterdam Island threatening the Amsterdam Albatross; on other islands introduced plants reduce potential nesting habitat.

Ingestion of plastic flotsam is another problem, one faced by many seabirds. The amount of plastic in the seas has increased dramatically since the first record in the 1960s, coming from waste discarded by ships, offshore dumping, litter on beaches, and waste washed to sea by rivers. Such plastic is impossible to digest and takes up space in the stomach or gizzard that should be used for food, or can cause an obstruction that starves the bird directly. Studies of birds in the North Pacific have shown that ingestion of plastics results in declining body weight and body condition (Spear et al. 1995). This plastic is sometimes regurgitated and fed to chicks; a study of Laysan Albatross chicks on Midway Atoll showed large amounts of ingested plastic in naturally dead chicks compared to healthy chicks killed in accidents (Auman 1997). While not the direct cause of death, this plastic causes physiological stress and likely causes the chick to feel full during feedings, reducing its food intake and the chances of survival.

Scientists and conservationists (particularly BirdLife International and their partners, who run the Save the Albatross campaign) are working with governments and fishermen to find solutions to the threats albatrosses face. Techniques such as setting long-line bait at night, dying the bait blue, setting the bait underwater, increasing the amount of weight on lines. and using bird scarers can all reduce the seabird by-catch (FAO 1999) For example, a collaborative study between scientists and fishermen in New Zealand successfully tested an underwater setting device for long-liners that set the lines below the reach of vulnerable albatross species (O'Toole and Molloy 2000). The use of some of these techniques in the Patagonian Toothfish fishery in the Falkland Islands is thought to have reduced the number of Black-browed Albatross taken by the fleet in the last 10 years (Reid et al. 2004).

One important step towards protecting albatrosses and other seabirds is the 2001 treaty the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, which came into force in 2004 and has been ratified by eight countries, Australia, Ecuador, New Zealand, Spain, South Africa, France, Peru and the United Kingdom. The treaty requires these countries to take specific actions to reduce by-catch, pollution, and to remove introduced species from nesting islands. The treaty has also been signed but not ratified by another three countries, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.

Conservationists have also worked on the field of island restoration, removing introduced species that threaten native wildlife, which protects albatrosses from introduced predators.

Taxonomy and evolution

The albatrosses comprise between 13 and 24 species in four genera. (The number of species is still a matter of some debate, 21 being a commonly accepted number.)

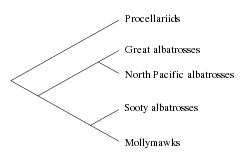

The four genera recognzed are the great albatrosses (Diomedea), the mollymawks (Thalassarche), the North Pacific albatrosses (Phoebastria), and the sooty albatrosses or sooties (Phoebetria). Of the four genera, the North Pacific albatrosses are considered to be a sister taxon to the great albatrosses, while the sooty albatrosses are considered closer to the mollymawks.

There is a lack of consensus on the taxonomy of the albatross group. The Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy places seabirds, birds of prey, and many others in a greatly enlarged order Ciconiiformes, whereas the ornithological organizations in North America, Europe, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand retain the more traditional order Procellariiformes.

The albatrosses are placed in the family Diomedeidae. They can be separated from the other Procellariiformes both genetically and through morphological characteristics, size, their legs, and the arrangement of their nasal tubes. (See Morphology and flight.)

Within the family, the assignment of genera has been debated for over a hundred years. Originally placed into a single genus, Diomedea, they were rearranged by Reichenbach into four different genera in 1852, then lumped back together and split apart again several times, acquiring 12 different genus names in total by 1965 (though never more than eight at one time). These 12 genera were Diomedea, Phoebastria, Thalassarche, Phoebetria, Thalassageron,, Diomedella, Nealbutrus, Rhothonia, Julietata, Galapagornis, Laysanornis, and Penthirenia).

By 1965, in an attempt to bring some order back to the classification of albatrosses, they were lumped into two genera, Phoebetria (the sooty albatrosses, which most closely seemed to resemble the procellarids and were at the time considered "primitive" ) and Diomedea (the rest of the albatrosses) (Alexander et al. 1965). Though there was a case for the simplification of the family (particularly the nomenclature), the classification was based on the morphological analysis of Elliott Coues in 1866, and paid little attention to more recent studies and even ignored some of Coues's suggestions.

More recent research by Gary Nunn of the American Museum of Natural History (1996) and other researchers around the world studied the mitochondrial DNA of all 14 accepted species, reporting that there were four, not two, monophyletic groups within the albatrosses (Nunn 1996). They proposed the resurrection of two of the old genus names, Phoebastria for the North Pacific albatrosses and Thalassarche for the mollymawks, with the great albatrosses retaining Diomedea and the sooty albatrosses staying in Phoebetria. Both the British Ornithologists' Union and the South African authorities split the albatrosses into four genera as Nunn suggested, and the change has been accepted by the majority of researchers.

While there is some agreement on the number of genera, there is less agreement on the number of species. Historically, up to 80 different taxa have been described by different researchers; most of these were incorrectly identified juvenile birds (Double and Chambers 2004). Based on the work on albatross genera, Robertson and Nunn (1998) went on in 1998 to propose a revised taxonomy with 24 different species, compared to the 14 then accepted. This interim taxonomy elevated many established subspecies to full species, but was criticised for not using, in every case, peer reviewed information to justify the splits.

Since then, further studies have in some instances supported or disproved the splits. A 2004 paper analysing the mitochondrial DNA and microsatellites agreed with the conclusion that the Antipodean Albatross and the Tristan Albatross were distinct from the Wandering Albatross, per Robertson and Nunn, but found that the suggested Gibson's Albatross, Diomedea gibsoni, was not distinct from the Antipodean Albatross (Burg and Croxall 2004). For the most part, an interim taxonomy of 21 species is accepted by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and many other researchers, though by no means all—in 2004, Penhallurick and Wink called for the number of species to be reduced to 13 (including the lumping of the Amsterdam Albatross with the Wandering Albatross) (Penhallurick and Wink 2004), although this paper was itself controversial (Double and Chambers 2004, Rheindt and Austin 2005). On all sides, there is the widespread agreement on the need for further research to clarify the issue.

Sibley and Ahlquist's (1990) molecular study of the evolution of the bird families has put the radiation of the Procellariiformes in the Oligocene period (35–30 million years ago). However, this group is speculated to have probably originated earlier, with a fossil sometimes attributed to the order, a seabird known as Tytthostonyx, being found in late Cretaceous rocks (70 million years ago). The molecular evidence suggests that the storm-petrels were the first to diverge from the ancestral stock, and the albatrosses next, with the procellarids and diving petrels separating later.

The earliest fossil albatrosses were found in Eocene to Oligocene rocks, although some of these are only tentatively assigned to the family and none appear to be particularly close to the living forms. They are Murunkus (Middle Eocene of Uzbekistan), Manu (early Oligocene of New Zealand), and an undescribed form from the Late Oligocene of South Carolina ([[United States). Similar to the last was Plotornis, formerly often considered a petrel but now accepted as an albatross. It is from the Middle Miocene of France, a time when the split between the four modern genera was already underway as evidenced by Phoebastria californica and Diomedea milleri, both being mid-Miocene species from Sharktooth Hill, California. These show that the split between the great albatrosses and the North Pacific albatrosses occurred by 15 million years ago (mya). Similar fossil finds in the southern hemisphere put the split between the sooties and mollymawks at 10 mya (Brooke 2004).

The fossil record of the albatrosses in the northern hemisphere is more complete than that of the southern, and many fossil forms of albatross have been found in the North Atlantic, which today has no albatrosses. The remains of a colony of Short-tailed Albatrosses have been uncovered on the island of Bermuda (Olson and Hearty 2003) and the majority of fossil albatrosses from the North Atlantic have been of the genus Phoebastria (the North Pacific albatrosses); one, Phoebastria anglica, has been found in deposits in both North Carolina (United States) and England.

Species

The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and BirdLife International, among others, recognize the interim taxonomy of 21 extant species. These are the following, arranged in the four recognized genera.

- Great albatrosses (Diomedea)

- Wandering Albatross D. exulans

- Antipodean Albatross D. (exulans) antipodensis

- Amsterdam Albatross D. (exulans) amsterdamensis

- Tristan Albatross D. (exulans) dabbenena

- Northern Royal Albatross D. (epomorpha) sanfordi

- Southern Royal Albatross D. epomophora

- North Pacific albatrosses (Phoebastria)

- Waved Albatross P. irrorata

- Short-tailed Albatross P. albatrus

- Black-footed Albatross P. nigripes

- Laysan Albatross P. immutabilis

- Mollymawks (Thalassarche)

- Black-browed Albatross T. melanophris

- Campbell Albatross T. (melanophris) impavida

- Shy Albatross T. cauta

- Chatham Albatross T. (cauta) eremita

- Salvin's Albatross T. (cauta) salvini

- Grey-headed Albatross T. chrysostoma

- Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross T. chlororhynchos

- Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross T. (chlororhynchos) carteri

- Buller's Albatross T. bulleri

- Sooty albatrosses (Phoebetria)

- Dark-mantled Sooty Albatross P. fusca

- Light-mantled Sooty Albatross P. palpebrata

Notes and references

- Åkesson, S., and H. Weimerskirch. 2005. "Albatross long-distance navigation: Comparing adults and juveniles." Journal of Navigation 58: 365-373.

- Alexander, W. B., C. A. Fleming, R. A. Falla, N. H. Kuroda, C. Jouanin, M. K. Rowan, R. C. Murphy, D. L. Serventy, F. Salomonsen, W. L. N. Ticknell, K. H.. Voous, J. Warham, G. E. Watson, J. M. Winterbottom, and W. R. P. Bourne. 1965. "Correspondence: The families and genera of the petrels and their names." Ibis 107: 401-5.

- Anderson, D. J., and F. Cruz. 1998. "Biology and management of the Waved Albatross at the Galapagos Islands." G. Roberston and R. Gales, eds., Albatross Biology and Conservation. Chipping Norton: Surrey Beatty and & Sons. ISBN 0949324825.

- Auman, H. J., J. P. Ludwig, J. P. Giesy, and T. Colborn. 1997. "Plastic ingestion by Laysan Albatross chicks on Sand Island, Midway Atoll, in 1994 and 1995." In G. Roberston and R. Gales, eds., Albatross Biology and Conservation. Chipping Norton: Surrey Beatty and & Sons. ISBN 0949324825.

- BBC News. 2005. Albatross chicks attacked by mice. Jonathan Amos, science writer. Retrieved March 6, 2006.

- Brooke, M. 2004. Albatrosses And Petrels Across The World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198501250.

- Brothers, N. P. 1991. "Albatross mortality and associated bait loss in the Japanese longline fishery in the southern ocean." Biological Conservation 55: 255-268.

- Burg, T. M., and J. P. Croxall. 2004. "Global population structure and taxonomy of the wandering albatross species complex." Molecular Ecology 13: 2345-2355.

- Carboneras, C. 1992. Family Diomedeidae (Albatross). In Handbook of Birds of the World Vol 1. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 8487334105.

- Cobley, N. D. 1996. An observation of live prey capture by a Black-browed Albatross Diomedea melanophrys. Marine Ornithology 24: 45-46. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Cocker, M., and R. Mabey. 2005. Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701169079.

- Croxall, J. P., and P. A. Prince. 1994. "Dead or alive, night or day: How do albatrosses catch squid?" Antarctic Science 6: 155–162.

- Croxall, J. P., J. R. D. Silk, R. A. Phillips, V. Afanasyev, and D. R. Briggs. 2005. "Global circumnaviagtions: Tracking year-round ranges of nonbreeding Albatrosses." Science 307: 249-250.

- Double, M. C., and G. K. Chambers. 2004. "The need for the parties to the Agreement on Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) to establish a robust, defendable and transparent decision-making process for the construction and maintenance of their species lists." Proceedings of the Scientific Meeting of Agreement on Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). Hobart, Australia. November 8-9, 2004.

- Fisher, H. I. 1976. "Some dynamics of a breeding colony of Laysan Albatrosses." Wilson Bulletin 88: 121-142.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). 1999. The incidental catch of seabirds by longline fisheries: Worldwide review and technical guidelines for mitigation. FAO Fisheries Circular No. 937. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- IUCN. 2004. Red list: Albatross species. World Conservation Union. Retrieved September 13, 2005.

- Jouventin, P., G. de Monicault, and J. M. Blosseville. 1981. "La danse de l'albatros, Phoebetria fusca." Behaviour 78: 43-80.

- Lequette, B., C. Verheyden, and P. Jowentin. 1989. Olfaction in Subantarctic seabirds: Its phylogenetic and ecological significance. The Condor 91: 732-135. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Nunn, G. B., J. Cooper, P. Jouventin, C. J. R. Robertson, and G. Robertson. 1996. Evolutionary relationships among extant albatrosses (Procellariiformes: Diomedeidae) established from complete cytochrome-b gene sequences. Auk 113: 784-801. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Olson, S. L., and P. J. Hearty. 2003. "Probable extirpation of a breeding colony of Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) on Bermuda by Pleistocene sea-level rise." Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 100(22): 12825-12829.

- O'Toole, D., and J. Molloy. 2000. Preliminary performance assessment of an underwater line setting device for pelagic longline fishing. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 34: 455-461.

- Penhallurick, J., and M. Wink. 2004. Analysis of the taxonomy and nomenclature of the Procellariformes based on complete nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Emu 104: 125-147.

- Pennycuick, C. J. 1982. "The flight of petrels and albatrosses (Procellariiformes), observed in South Georgia and its vicinity." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 300: 75–106.

- Pickering, S. P. C., and S. D. Berrow. 2001. Courtship behaviour of the Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans at Bird Island, South Georgia. Marine Ornithology 29: 29-37. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Prince, P. A., N. Huin, and H. Weimerskirch. 1994. "Diving depths of albatrosses." Antarctic Science 6:(3): 353-354.

- Reid, A. T., B. J. Sullivan, J. Pompert, J. W. Enticott, and A. D. Black. 2004. "Seabird mortality associated with Patagonian Toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) longliners in Falkland Islands waters." Emu 104(4): 317-325.

- Rheindt, F. E., and J. Austin. 2005. "Major analytical and conceptual shortcomings in a recent taxonomic revision of the Procellariiformes: A reply to Penhallurick and Wink" (2004). Emu 105: 181-186.

- Robertson, C. J. R. 1993. "Survival and longevity of the Northern Royal Albatross." Diomedea epomophora sanfordi at Taiaroa Head, 1937-93. Emu 93: 269-276.

- Robertson, C. J. R., and G. B. Nunn. 1998. "Towards a new taxonomy for albatrosses." In G. Robertson and R. Gales (eds.), Proceedings First International Conference on the Biology and Conservation of Albatrosses. Chipping Norton:Surrey Beatty & Sons, 13-19.

- Safina, C. 2002. Eye of the Albatross: Visions of Hope and Survival. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0805062297.

- Sibley, C. G., and J. Ahlquist. 1990. Phylogeny and Classification of Birds. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Spear, L. B., D. G. Ainley, and C. A. Ribic. 1995. "Incidence of plastic in seabirds from the tropical Pacific, 1984–91: relation with distribution of species, sex, age, season, year and body weight." Marine Environmental Research 40: 123–146.

- Tickell, W. L. N. 2000. Albatrosses. Sussex: Pica Press. ISBN 1873403941.

- Warham, J. 1996. The Behaviour, Population, Biology and Physiology of the Petrels. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0127354158.

- Warham, J. 1990. The Petrels: Their Ecology and Breeding Systems. London: Academic Press.

- Warham, J. 1976. The incidence, function and ecological significance of petrel stomach oils. Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society 24: 84-93. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Weimerskirch, H. T. Guionnet, J. Martin, S. A. Shaffer, and D. P. Costa. 2000. "Fast and fuel efficient? Optimal use of wind by flying albatrosses." Proc. Biol. Sci. 267(1455): 1869-1874.

External links

All links retrieved June 17, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.