| Saint Albertus Magnus | |

|---|---|

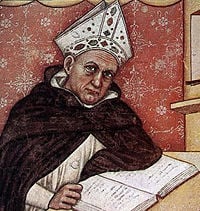

Albertus Magnus (fresco, 1352, Treviso, Italy) | |

| Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | c. 1193/1206Â in Lauingen, Bavaria |

| Died | November 15, 1280Â in Cologne, Germany |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 1622 |

| Canonized | 1931

by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | St. Andreas in Cologne |

| Feast | November 15 |

| Patronage | Cincinnati, Ohio; medical technicians; natural sciences; philosophers; scientists; students; World Youth Day |

Albertus Magnus (1193/1206 â November 15, 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, was a Dominican friar who became famous for his comprehensive knowledge and for demonstrating that the study of science was compatible with religious faith. He is considered to be the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages, and was known as âDoctor Universalisâ because of his comprehensive knowledge of all areas of medieval science and philosophy. He wrote a detailed commentary on every work attributed to Aristotle, and is considered the first medieval scholar to apply Aristotelian philosophy to contemporary Christian thought. Albertus tried to dispel what he thought to be the theological "errors" which had arisen from the Arab and Jewish commentaries on Aristotle.

He was teacher and mentor to Thomas Aquinas, with whom he worked closely at the Studium Generalein (Dominican House of Studies) in Cologne. A year before his death, he made a journey to Paris to defend the orthodoxy of Aquinas against the accusation of Stephen Tempier and others who wished to condemn his writings as being too favorable to the âunbelieving philosophers.â Albertus was canonized as a Catholic saint in 1931, and is honored by Roman Catholics as one of the 33 Doctors of the Church.

Biography

Albertus Magnus was born the eldest son of Count Bollstadt in Lauingen, Bavaria, Germany on the Danube, sometime between 1193 and 1206. The term "magnus" is not descriptive; it is the Latin equivalent of his family name, de Groot.

Albertus was educated principally at Padua, Italy, where he received instruction in Aristotle's writings. After an alleged encounter with the Blessed Virgin Mary, he joined the Dominican Order in 1223, attracted by the preaching of Blessed Jordan of Saxony. He and studied theology under the Dominicans at Bologna and possibly in Paris or Cologne.

After completing his studies he taught theology at Cologne, where the order had a house, and at Regensburg, Freiburg, Strasbourg and Hildesheim. In 1245 he was called from Cologne to Paris, received his doctorate and taught for some time, in accordance with the regulations, with great success. At Cologne one of his students had been Thomas Aquinas; he accompanied Albertus to Paris in 1245 and returned to Cologne with him in 1248, when Magnus was appointed to organize the new Studium Generale (House of Studies) there. Magnus was made regent, and Aquinas became second professor and Magister Studentium (âMaster of Studentsâ).

At the General Chapter of the Dominicans in 1250, together with Aquinas and Peter of Tarentasia (later Pope Innocent V), he drew up rules for the course of studies and the system of graduation in the Dominican Order. In 1254 he was elected provincial of the Dominican Order in Germany. In 1256 he traveled to Rome to defend the Mendicant Orders against the attacks of William of St. Amour, whose book, De novissimis temporum periculis, was condemned by Pope Alexander IV, on October 5, 1256. He also spoke out against the errors of the Averroists with a treatise, De Unitate Intellectus Contra Averroem. In 1257 he resigned the office of provincial in 1257 and devoted himself to study and teaching.

In 1260 Pope Alexander IV made him bishop of Regensburg, a position which he resigned after the popeâs death in 1261 in order to return to his duties as a professor in Cologne. In 1270 he sent a memoir to Paris to aid Aquinas in combating Siger de Brabant and the Averroists. The remainder of his life was spent partly in preaching throughout Bavaria and the adjoining districts, partly in retirement in the various houses of his order.

In 1270 he preached the eighth Crusade in Austria. In 1274 he was called by Pope Gregory X to the Council of Lyons, in which he was an active participant. On his way to Lyons he learned of the death of Aquinas, and is said to have shed tears afterward every time his former studentâs name was mentioned. In 1277 he traveled to Paris to defend the orthodoxy of Aquinas against the accusation of Stephen Tempier and others who wished to condemn his writings as being too favorable to the âunbelieving philosophers.â After suffering a collapse in 1278, he died on November 15, 1280, in Cologne, Germany. His tomb is in the crypt of the Dominican Church of St. Andreas in Cologne. Albertus was beatified in 1622, and canonized and also officially named a Doctor of the Church in 1931 by Pope Pius XII. His feast day is celebrated on November 15.

Albertus is frequently mentioned by Dante Alighieri, who made his doctrine of free will the basis of his ethical system. In his Divine Comedy, Dante places Albertus with his pupil Thomas Aquinas among the great lovers of wisdom (Spiriti Sapienti) in the Heaven of the Sun.

Works

The complete works of Albertus have been published twice: in Lyons in 1651, as 21 volumes, edited by Father Peter Jammy, O.P.; and in Paris (Louis Vivès) in 1890-1899 as 38 volumes, under the direction of AbbĂŠ Auguste Borgnet, of the diocese of Reims. He wrote prolifically and displayed an encyclopedic knowledge of all the topics of medieval science, including logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, mineralogy, chemistry, zoology, physiology, and phrenology, much of it the result of logic and observation. He was the most widely-read author of his time and came to be known as âDoctor Universalisâ for the extent of his knowledge.

Albertus ensured the advancement of medieval scientific study by promoting Aristotelianism against the reactionary tendencies of the conservative theologians of his time. Using Latin translations and the notes of the Arabian commentators, he digested, systematized and interpreted the whole of Aristotle's works in accordance with church doctrine (he came to be so closely associated with Aristotle that he was sometimes referred to as "Aristotle's ape"). At the same time, he allowed for the credibility of Neoplatonic speculation, which was continued by mystics of the fourteenth century, such as Ulrich of Strasbourg. He exercised his greatest influence through his writings on natural science, and was more of a philosopher than a theologian.

His philosophical works, occupying the first six and the last of the 21 volumes published in 1651, are generally divided according to the Aristotelian scheme of the sciences. They consist of interpretations and summaries of relevant works of Aristotle, with supplementary discussions on questions of contemporary interest, and occasional divergences from the opinions of Aristotle.

His principal theological works are a commentary in three volumes on the Books of the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Magister Sententiarum), and the Summa Theologiae in two volumes. This last is, in substance, a repetition of the first in a more didactic form.

Albertus as Scientist

Like his contemporary, Roger Bacon (1214-1294), Albertus was an avid student of nature, and conducted careful observations and experiments in every area of medieval science. Together these two men demonstrated that the Roman Catholic Church was not opposed to the study of nature, and that science and theology could supplement each other. Albertus was sometimes accused of neglecting theology in favor of the natural sciences, but his respect for the authority of the church and for tradition, and the circumspect way in which he presented the results of his investigations, ensured that they were generally accepted by the academic community. He made substantial contributions to science; Alexander von Humboldt praised his knowledge of physical geography, and the botanist Meyer credits him with making âastonishing progress in the science of nature.â

"No botanist who lived before Albert can be compared with him, unless it be Theophrastus, with whom he was not acquainted; and after him none has painted nature in such living colors, or studied it so profoundly, until the time of Conrad, Gesner, and Cesalpini. All honor, then, to the man who made such astonishing progress in the science of nature as to find no one, I will not say to surpass, but even to equal him for the space of three centuries." (Meyer, Gesch. der Botanik)

Albertus gave a detailed demonstration that the Earth was spherical, and it has been pointed out that his views on this subject led eventually to the discovery of America (cf. Mandonnet, in "Revue Thomiste," I, 1893; 46-64, 200-221). Albertus was both a student and a teacher of alchemy and chemistry. In 1250 he isolated arsenic, the first element to be isolated since antiquity and the first with a known discoverer. Some of his critics alleged that he was a magician and that he made a demonic automata (a brass head, able to speak by itself). Albertus himself strongly denied the possibility of magic.

Music

Albertus is known for his enlightening commentary on musical practice of the time. Most of his musical observations are given in his commentary on Aristotle's Poetics. Among other things, he rejected the idea of "music of the spheres" as ridiculous; he supposed that the movement of astronomical bodies was incapable of generating sound. He also wrote extensively on proportions in music, and on the three different subjective levels on which plainchant (traditional songs used in liturgy) could work on the human soul: purging of the impure; illumination leading to contemplation; and nourishing perfection through contemplation. Of particular interest to twentieth-century music theorists is the attention he paid to silence as an integral part of music.

Philosophy

During the thirteenth century, the study of philosophy was not distinct from the study of the physical sciences. Albertus organized the form and method of Christian theology and philosophy. Together with Alexander Hales (d. 1245), he pioneered the application of Aristotelian methods and principles to the study of Christian doctrine, and initiated the scholastic movement which attempted to reconcile faith with reason. After Averroes, Albertus was the main commentator on the works of Aristotle. During the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, so many errors had been drawn from Jewish and Arabic commentaries on Aristotleâs works that from 1210-1215, the study of Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics was forbidden at Paris. Albert realized that the enthusiasm of scholars for philosophical studies could not be stifled, and set out to follow the directive of Saint Augustine, that the truths of the pagan philosophers should be adopted by the faithful, and the "erroneous" opinions should be discarded or given a Christian interpretation.

To counter the rationalism of Abelard and his followers, Albertus made the distinction between truths which could be inferred from nature and mysteries which could only be known through revelation. He wrote two treatises against Averroism, which claimed that there was but one rational soul for all men and thus denied individual immortality and individual responsibility during earthly life. To refute pantheism Albertus clarified the doctrine of universals, distinguishing among the universal ante rem (an idea or archetype in the mind of God), in re (existing or capable of existing in many individuals), and post rem (as a concept abstracted by the mind, and compared with the individuals of which it can be predicated).

Albertus regarded logic as a preparation for philosophy, teaching the use of reason to move from the known to the unknown. He distinguished between contemplative philosophy (embracing physics, mathematics and metaphysics); and practical philosophy, or ethics, which was monastic (for the individual), domestic (for the family) and political (for the state or society).

Albertus also made a great contribution as the mentor and teacher of Thomas Aquinas, whose Summa Theologica was inspired by that of Albertus.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Best, Michael R. and Frank H. Brightman (eds.). The Book of Secrets of Albertus Magnus: Of the Virtues of Herbs, Stones, and Certain Beasts, Also a Book of the Marvels of the World. Weiser Books, 2000.

- RĂźhm, Gerhard. Albertus Magnus Angelus. Residenz, 1989.

- Senner, Walter. Albertus Magnus. Akademie-Verlag, 2001.

- Weisheipl, James A. (ed.). Albertus Magnus and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays, 1980 (Studies and Texts). Pontifical Inst. of Medieval, 1980.

External links

All links retrieved June 17, 2023.

- Albert the Great â Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- St. Albertus Magnus â Catholic Encyclopedia

- âAstrology & Magic of Albertus Magnusâ â Renaissance Astrology by Christopher Warnock

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.