Axum

| Aksum* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Reference | 15 |

| Region** | Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Axum, or Aksum, is a city in northern Ethiopia named after the Kingdom of Aksum, a naval and trading power that ruled the region from ca. 400 B.C.E. into the tenth century. The kingdom adopted the religion of Christianity in the fourth century C.E. and was known in medieval writings as "Ethiopia." Renowned not only for its long history of prosperity accrued from economic trade with Rome, India, and elsewhere, but also for its alleged connection with the Queen of Sheba, many Ethiopians also firmly believe that Axum is the current resting place of the Biblical Ark of the Covenant. These celebrated historical connections still play an important role in the religious life of its people. Today, seventy-five percent of its inhabitants are members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The remainder of the population is Sunni Muslim and P'ent'ay (Protestant and other non-Orthodox Christians).

The ancient African civilization of Axum flourished for over a thousand years due to the emphasis it placed on commerce and trade. It minted its own coins by the third century, converting in the fourth century to Christianity, as the second official Christian state (after Armenia) and the first country to feature the cross on its coins. It grew to be one of the four greatest civilizations in the world, on a par with China, Persia, and Rome. In the seventh century, with the advent of Islam in Arabia, Aksum's trade and power began to decline and the center moved farther inland to the highlands of what is today Ethiopia.

Due to their famous history, UNESCO added Aksum's archaeological sites to its list of World Heritage Sites in the 1980s.

Location

Axum is located in the Mehakelegnaw Zone of the Tigray Region near the base of the Adwa mountains in Ethiopia. The city has an elevation of 2,130 meters above sea level. In the modern world, the city of Axum has an estimated total population of 47,320 of whom 20,774 are males and 21,898 are females.[1]

History

The Kingdom of Axum can be traced back to biblical times. According to legend, the Queen of Sheba was born in Axum from where she famously traveled to Jerusalem to meet King Solomon. The city was already the center of a marine trading power known as the Aksumite Kingdom by the time of the Roman Empire. Indeed, Roman writings describe the expansion of Rome into northern Africa and encounters with Axum.

The kingdom of Aksum had its own written language called Ge'ez, and also developed a distinctive architecture exemplified by giant obelisks, the oldest of which date from 5,000-2,000 B.C.E.[2] This kingdom was at its height under king Ezana, baptized as Abreha, in the 300s C.E. (which was also when it officially embraced Christianity).[3] After Axum became a Christian kingdom, it allied itself with the Byzantium Empire against the Persian Empire.

Following the rise of Islam, Axum was again involved in the intrigues of regional politics when a party of Prophet Muhammaed's followers found refuge in Axum from the hostile Quraish clan (see below). It is believed that the Kingdom of Axum initially had good relations with Islam]; however, the kingdom began is long, slow decline after the 7th century due partly to Islamic groups contesting trade routes. Eventually Aksum was cut off from its principal markets in Alexandria, Byzantium and Southern Europe and its trade share was captured by Arab traders of the era. The Kingdom of Aksum also quarreled with Islamic groups over religion. Eventually the people of Aksum were forced south and their civilization declined. As the kingdom's power declined so did the influence of the city, which is believed to have lost population in the decline similar to Rome and other cities thrust away from the flow of world events. The last known (nominal) king to reign was crowned ca. tenth century, but the kingdom's influence and power ended long before that. Its decline in population and trade then contributed to the shift of the power center of the Ethiopian Empire so that it moved further inland and bequeathed its alternative place name (Ethiopia) to the region, and eventually, the modern state.[4]

Religion

Axum is considered to be the holiest city in Ethiopia and is an important destination of pilgrimages.[5] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church claims that the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum houses the Biblical Ark of the Covenant in which lies the Tablets of Law upon which the Ten Commandments are inscribed.[5] This same church was the site at which Ethiopian emperors were crowned for centuries until the reign of Fasilides, then again beginning with Yohannes IV until the end of the empire. Significant religious festivals are the T'imk'et Festival (known as the Epiphany in western Christianity) on January 7 and the Festival of Maryam Zion in late November.

The connection of Axum with Islam is very old. According to ibn Hisham, when Muhammad faced oppression from the Quraish clan, he sent a small group that included his daughter Ruqayya and her husband Uthman ibn Affan, whom Ashama ibn Abjar, the king of Axum, gave refuge to, and protection to, and refused the requests of the Quraish clan to send these refugees back to Arabia. These refugees did not return until the sixth year of the Hijra (628), and even then many remained in Ethiopia, eventually settling at Negash in eastern Tigray.

There are different traditions concerning the effect these early Muslims had on the ruler of Axum. The Muslim tradition is that the ruler of Axum was so impressed by these refugees that he became a secret convert.[6] On the other hand, Arabic historians and Ethiopian tradition states that some of the Muslim refugees who lived in Ethiopia during this time converted to Orthodox Christianity. Worth mentioning is a second Ethiopian tradition that, on the death of Ashama ibn Abjar, Muhammed is reported to have prayed for the king's soul, and told his followers, "Leave the Abyssinians in peace, as long as they do not take the offensive.”[7]

Although Axumite Muslims have attempted to build a mosque in this holy Ethiopian town, Orthodox residents, and the emperors of the past have replied that they must be allowed to build an Ethiopian Orthodox church in Mecca if the Muslims are to be allowed to build a mosque in Axum.

Sites of interest

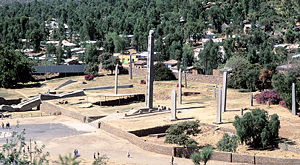

The major Aksumite monuments in the town are stelae; the largest number lie in the Northern Stelae Park, ranging up to the 33 meters (33 meters high, 3.84 meters wide, 2.35 meters deep, 520 tonnes) Great Stele, believed to have fallen and broken during construction. The tallest standing is the 24 meters (20.6 meters high, 2.65 meters wide, 1.18 meters, deep 160 tonnes) King Ezana's Stele. Another stelae (24.6 meters high, 2.32 meters wide, 1.36 meters deep, 170 tonnes) looted by the Italian army was returned to Ethiopia in 2005 and reinstalled July 31, 2008.[8]

In 1937, a 24-meter tall, 1700-year-old obelisk standing in Axum was cut into three parts by Italian soldiers and shipped to Rome to be re-erected. The obelisk is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of engineering from the height of the Axumite empire. Despite a 1947 United Nations agreement that the obelisk would be shipped back, Italy balked, resulting in a long-standing diplomatic dispute with the Ethiopian government, which views the obelisk as a symbol of national identity. In April 2005, Italy finally returned the obelisk pieces to Axum amidst much official and public rejoicing, Italy also covered the $4 million costs of the transfer. UNESCO has assumed responsibility for the re-installation of this stele in Axum, and as of the end of July 2008 the obelisk has been reinstalled (see panographic photos in external links below). Rededication of the obelisk took place on September 4, 2008, in Paris, France with Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi dedicating the obelisk to Italian President Giorgio Napolitano for his kind efforts in returning the obelisk. Three more stelae measure: 18.2 meters high, 1.56 meters wide, 0.76 meters deep, 56 tonnes; 15.8 meters high, 2.35 meters wide, one meter deep, 75 tonnes; 15.3 meters high, 1.47 meters wide, 0.78 meters deep, 43 tonnes.[9] The stelae are believed to mark graves and would have had cast metal discs affixed to their sides, which are also carved with architectural designs. The Gudit Stelae to the west of town, unlike the northern area, are interspersed with mostly fourth-century tombs.

Other features of the town include St Mary of Zion church, built in 1665 and said to contain the Ark of the Covenant (a prominent twentieth-century church of the same name neighbors), archaeological and ethnographic museums, the Ezana Stone written in Sabaean, Ge'ez and Ancient Greek in a similar manner to the Rosetta Stone, King Bazen's Tomb (a megalith considered to be one of the earliest structures), the so-called Queen of Sheba's Bath (actually a reservoir), the fourth-century Ta'akha Maryam and sixth-century Dungur palaces, the monasteries of Abba Pentalewon and Abba Liqanos and the Lioness of Gobedra rock art.

Local legend claims the Queen of Sheba lived in the town.

Notes

- ↑ CSA 2005 National Statistics, Table B.4.

- ↑ Herausgegeben von Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), 871.

- ↑ J.D. Fage, A History of Africa (London: Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-25248-2), 53-54.

- ↑ G. Mokhtar, UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. II, Abridged Edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990, ISBN 0-85255-092-8), 215-35.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mike Hodd, Footprint East Africa Handbook (New York: Footprint Travel Guides, 2002, ISBN 1-900949-65-2), 859.

- ↑ Ibn Ishaq, The Life of Muhammad (Oxford, 1955), 657-58.

- ↑ Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (New York: Palgrave, 2000), 42f.

- ↑ "Mission accomplished: Aksum Obelisk successfully reinstalled" (August 1, 2008) Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ↑ Chris Scarre, Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World (Thames & Hudson, 1999, ISBN 978-0500050965).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heldman, Marilyn. African Zion, the Sacred Art of Ethiopia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0300067149

- Kobishchanov, Yuri M. Axum (Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator). University Park, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 1979. ISBN 0-271-00531-9

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press. 1991. ISBN 0-7486-0106-6 online edition Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Excavations at Aksum: An account of research at the ancient Ethiopian capital directed in 1972-74 by the late Dr Nevill Chittick. London: British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1989. ISBN 0-500-97008-4

- Phillipson, David W. Ancient Ethiopia. Aksum: Its antecedents and successors. London: The British Brisith Museum, 1998. ISBN 978-0714125398

- Phillipson, David W. Archaeology at Aksum, Ethiopia, 1993-97. London: Brisith Institute in Eastern Africa, 2000. ISBN 978-0521832366

- Scarre, Chris. Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, 1999. ISBN 978-0500050965

- Sellassie, Sergew Hable. Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270. Addis Ababa: United Printers, 1972.

External links

All links retrieved August 23, 2023.

- Aksum Ethiopian Treasures.

- Aksum UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- "Foundations of Aksumite Civilization and Its Christian Legacy (1st–7th century)" The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.