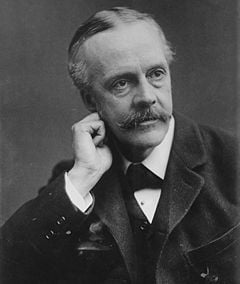

Described as a 'scrap of paper' that changed history, the Balfour Declaration led to the creation of the modern State of Israel as a land to which all Jews could return, if they wish. The Declaration was a letter dated November 2, 1917, from Arthur James Balfour (1848–1930), British secretary of state for foreign affairs, formerly prime minister (1902–1905), to Lord Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation, a private Zionist organization committed to the creation of a Jewish homeland in Israel. The letter stated the position, agreed to at a British cabinet meeting on October 31, 1917, that the British government supported Zionist plans for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine, with the condition that nothing should be done that might prejudice the rights of existing communities there. This was a reference to the Arab population, mainly Muslim, although it included Christians too. The implications of this inherent contradiction took some time to became clear.

The Balfour Declaration led to the 1922 League of Nations mandate for the administration of the former Ottoman territory of Palestine being given to the United Kingdom. Phrases from the 1917 declaration regarding the establishment of a homeland for the Jews while not prejudicing the rights of other people resident in Palestine—that is, of the Arabs—were incorporated into the 1922 mandate. The end result was the creation of the modern state of Israel as a land to which all Jews can return, if they wish. As well as making promises to the Jews, the British had also given certain assurances to the Arabs about territory that they might control after World War I, assuming victory against the Ottoman Empire.

Some regard the Balfour Declaration as providential, enabling the return of the Jews to Israel and eventually the unfolding of biblical prophecy. However, no clarity evolved on how a Jewish homeland might be established, or on how the rights of Arabs might be protected. Although the United Nations in 1947 drew up plans for two states, no mechanism for establishing these was created. Lack of clarity on how a viable two-state reality could be achieved continues to characterize international involvement in efforts to end the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian people.

The Historical Context

The Declaration was produced during the First World War when Britain was at war with the Ottoman Empire. It was not at all clear which side would win and Britain was searching for any allies which could help to weaken Germany and the Ottomans. The Ottoman Empire included the whole of the Middle East.

Promises to the Arabs

As part of this search for allies British officials in Egypt, had been corresponding with the Sharif of Makkah, Hussein bin Ali. Britain wanted the Arabs to rebel against the Ottoman Empire so as to weaken it by tying up troops who would otherwise be deployed against the Allies. Sir Henry McMahon (1862–1949), British High Commissioner in Egypt led the negotiations with the Sharif. Hussein aspired to an Arab state, stretching from Syria to Yemen. In an exchange of letters (the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence) McMahon promised on October, 24 1915 that Britain would support Arab independence except in the following areas:

The districts of Mersin and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, cannot be said to be purely Arab, and must on that account be excepted from the proposed delimitation. . . . Subject to the above modifications, Great Britain is prepared to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs in all the regions within the limits demanded by the Sharif of Mecca.[1]

On this understanding the Arabs established a military force under the command of Hussein's son Faisal which fought, with inspiration from Lawrence of Arabia, against the Ottoman Empire during the Arab Revolt. After the war Arabs did get their independence from the Ottomans and the countries of Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia were established.

Many years later McMahon, in a letter to the London Times on July 23, 1937, wrote:

I feel it my duty to state, and I do so definitely and emphatically, that it was not intended by me in giving this pledge to King Hussein to include Palestine in the area in which Arab independence was promised. I had also every reason to believe at the time that the fact that Palestine was not included in my pledge was well understood by King Hussein.

Sykes-Picot Agreement

At the same time as McMahon was negotiating with the Sharif, the governments of Britain and France, with the assent of Russia were drawing up an understanding defining their respective spheres of influence and control in the Middle East after the expected downfall of the Ottoman Empire. It was quite normal in those days for the victors of war to divide up the spoils and redraw maps. The agreement was negotiated in November 1915 by the French diplomat François Georges-Picot and Briton Mark Sykes. Britain was allocated control of areas roughly comprising Jordan, Iraq and a small area around Haifa, to allow access to a Mediterranean port. France was allocated control of south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. Russia was to get Constantinople and the Ottoman Armenian vilayets. The region of Palestine was slated for international administration pending consultations with Russia and other powers. The controlling powers were left free to decide on state boundaries within these areas. The agreement had been made in secret. Sykes was also not affiliated with the Cairo office that had been corresponding with Sharif Hussein bin Ali, and was not fully aware of what had been promised the Arabs.

This agreement is seen by many as conflicting with the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence of 1915–1916. The conflicting agreements are the result of changing progress during the war, switching in the earlier correspondence from needing Arab help to subsequently trying to enlist the help of Jews in the United States in getting the US to join the First World War. There were also large Jewish populations in Germany and other European countries whose support the British also wanted to win.

British pro-Jewish Sympathy

The Jews had been expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I. However, following the Reformation the Bible was translated into English. After reading the Old Testament prophecies, there developed considerable support for the restoration of the Jews to the Holy Land among Puritans. As early as 1621 the British MP Sir Henry Finch had written a book entitled The World's Great Restoration which advocated returning Jews to Palestine. Protestants identified themselves with the Lost Tribes of Israel and they believed that, following Daniel 12:7, the return of Christ would only happen after the Jews had been scattered throughout the world. So it was necessary that they be scattered in Britain too. They also believed that the return of Christ would only happen after the Jews were restored to their land. Some believed they also had to be converted to Christianity.

In 1655, some Jews approached Oliver Cromwell for permission to settle in England. He consulted the lawyers who told him there was no statute preventing them from coming. So they came and were allowed to settle in Britain as full citizens, apart from the usual restrictions that applied to non-Anglicans. They prospered and soon rose to prominent positions in English society. They contributed to the development of industry, commerce, charity, education, medicine, welfare, and horse racing as well as banking and finance. Compared to other European countries England was decidedly philo-semitic.

Britain did not only welcome Jews, from 1745 she started to speak up for and help Jews abroad. Palmerston, (1784–1865) as foreign secretary, supported the return of Jews to Palestine and several times intervened to protect Jews in foreign countries. Jews also gave considerable aid to England financing William of Orange's invasion of England in 1688 as well as the coalition against Napoleon.

Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881), was born a Jew but was baptized into the Church of England when he was 13 after his father abandoned Judaism. He was elected to Parliament in 1837 and in 1868 became Prime Minister. Disraeli openly championed the intellectual and cultural achievements of the Jews and in his novels he presented them so positively that he influenced a generation. Disraeli may have believed that the destinies of the British and the Jews were somehow linked. As early as the 1840s, Lords Shaftesbury (1801–1885) as well as Palmerston (1784–1865) had supported the idea of a Jewish colony in Palestine. In 1903, the British offered the Zionists part of Uganda in Africa for their homeland. This was rejected in favor of Palestine.

Among the British ruling class in the early twentieth century there were many committed Zionists such as Winston Churchill, Lloyd George (Prime Minster), Arthur Balfour (Prime Minister, Foreign Secretary) and Sir Edward Grey (Foreign Secretary) to name but a few. They mostly believed in Zionism for religious or humanitarian reasons. Balfour himself believed that a national homeland was not a gift to the Jewish people but an act of restitution, giving Jews back something that had been stolen from them in the early days of the Christian era.[2] When Chaim Weizmann came to Britain to promote the idea of a Jewish homeland he found he was pushing at an open door.

Negotiation of the Balfour Declaration

One of the main Jewish figures who negotiated the granting of the declaration was Chaim Weizmann, the leading spokesman for organized Zionism in Britain. He was born in Russia but went to England as professor of chemistry at Manchester University in 1904. There he met Arthur Balfour who was a Member of Parliament for Manchester. He was also introduced to Winston Churchill and Lloyd George. Together with the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel he started a campaign to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann helped Lord Rothschild to draw up a draft declaration. It originally contained three important elements: The whole of Palestine was to be the national home of the Jews; there was to be unrestricted Jewish immigration; and the Jews would be allowed to govern themselves. The draft would have been agreed by the British cabinet except that Edwin Montagu, an anti-Zionist Jew and Secretary for India, objected and insisted that the rights of the Arabs be protected. So the declaration was published without these three elements.

As a chemist, Weizmann was the father of industrial fermentation and discovered how to synthesize acetone via fermentation. Acetone is needed in the production of cordite, a propellant needed to lob artillery shells. Germany had a corner on a key acetone ingredient, calcium acetate. Without calcium acetate, Britain could not produce acetone and without acetone there would be no cordite. Without cordite, Britain may have lost World War I. When Balfour asked what payment Weizmann required for the use of his process, Weizmann responded, "There is only one thing I want: A national home for my people." He eventually received both payments for his discovery and a role in the history of the origins of the state of Israel.

Text of the Declaration

The declaration, described as a 'scrap of paper' that changed history,[3] is a typed letter signed in ink by Balfour. It reads as follows:

Foreign Office,

November 2nd, 1917.

Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet.

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country".

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur James Balfour

The 'Twice-Promised Land'

The debate regarding Palestine derived from the fact that it is not explicitly mentioned in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence. The Arab position was that "portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo..." could not refer to Palestine since that lay well to the south of the named places. In particular, the Arabs argued that the vilayet (province) of Damascus did not exist and that the district (sanjak) of Damascus covered only the area surrounding the city itself and furthermore that Palestine was part of the vilayet of 'Syria A-Sham', which was not mentioned in the exchange of letters.[4] The British position, which it held consistently at least from 1916, was that Palestine was intended to be included in the phrase. Each side produced supporting arguments for their positions based on fine details of the wording and the historical circumstances of the correspondence. For example, the Arab side argued that the phrase "cannot be said to be purely Arab" did not apply to Palestine, while the British pointed to the Jewish and Christian minorities in Palestine.

In response to growing criticism arising from the mutually irreconcilable commitments undertaken by the United Kingdom in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Balfour declaration, the Churchill White Paper, 1922 stated that

it is not the case, as has been represented by the Arab Delegation, that during the war His Majesty's Government gave an undertaking that an independent national government should be at once established in Palestine. This representation mainly rests upon a letter dated the 24th October, 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, then His Majesty's High Commissioner in Egypt, to the Sharif of Mecca, now King Hussein of the Kingdom of the Hejaz. That letter is quoted as conveying the promise to the Sherif of Mecca to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty's Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir Henry McMahon's pledge.[5]

A committee established by the British in 1939 to clarify the various arguments did not come to a firm conclusion in either direction.[6]

Still it was always recognized that what had been done was exceptional and ethically dubious. In a 1919 memorandum he wrote as a Cabinet Minister, Balfour wrote of these contradictory assurances as follows:

The contradiction between the letter of the Covenant is even more flagrant in the case of the independent nation of Palestine than in that of the independent nation of Syria. For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country, though the American Commission has been going through the forms of asking what they are. The four great powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder importance than the desire and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion, that is right.[7]

The British Foreign Office opposed British support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland because it seriously damaged British interests in the Arab world.

Notes

- ↑ October 24 1915 letter from Sir Henry McMahon, High Commissioner in Egypt, to Sherif Husayn of Mecca, The World War I Document Archive. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Nicholas Bethel, The Palestine Triangle (London: Andre Deutsch, 1979, ISBN 023397069X)

- ↑ Donald Macintyre, "The birth of modern Israel: A scrap of paper that changed history" The Independent (May 26, 2005). Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Gideon Biger, The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947 (London: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0714656542), 48.

- ↑ British White Paper of June 1922, The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Report of 1939 British committee on the Hussein-McMahon correspondence, archived at UNISPAL. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Edward Said, Question of Palestine (Vintage Books, 1992, ISBN 0679739882), 16, and quoted by The Origin of the Palestine-Israeli Conflict 2nd Edition, 2002, Jews for Justice. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bethel, Nicholas. The Palestine Triangle. London: Andre Deutsch, 1979. ISBN 023397069X

- Biger, Gideon. The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0714656542

- Defries, Harry. Conservative Party Attitudes to Jews 1900-1950. Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0714652210

- Khouri, Fred John. The Arab-Israeli Dilemma. Syracuse University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0815623403

- Said, Edward. Question of Palestine. Vintage Books Edition, 1992. ISBN 0679739882

- Schneer, Jonathan. The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Random House, 2010. ISBN 978-1400065325

External Links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- The Balfour Declaration, November 2, 1917

- League of Nations Palestine Mandate

- United Nations Partition Plan, September 1947

- The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, May 14, 1948

- British White Paper of June 1922

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.