Bar Kochba

Simon bar Kokhba (Hebrew: שמעון בר כוכבא, also transliterated as Bar Kokhva or Bar Kochba) was a messianic Jewish leader who led a major revolt against the Roman Empire in 132 C.E., establishing an independent Jewish state of Israel which he ruled for three years as Nasi ("prince," or "president"). His state was conquered by the Romans in late 135 C.E. following a bloody two-year war.

Originally named ben Kosiba (בן כוזיבא), he was given the surname Bar Kokhba, meaning "Son of the Star," by the leading Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva, who believed him to be the promised Messiah.

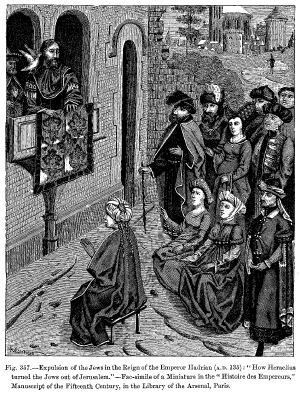

The eventual failure of Bar Kokhba’s revolt resulted in the deaths of possibly hundreds of thousands of Jews, the expulsion of the Jews from Jerusalem, and the end of the Jewish intellectual center at Jamnia. Henceforth, Babylon would be the primary center of Talmudic scholarship until the rise of European Jewry in the late Middle Ages. Judaism would not become a political force in Palestine again until the emergence of Zionism in the twentieth century.

In an ironic way, Bar Kokhba could be seen as the most successful would-be Messiah in Jewish history. Despite the folly and self-defeating outcome of a violence-based project, he can be described as the only messianic claimant to have actually established an independent Jewish nation (fleeting though it was).[1]

Background

The first Jewish Revolt of 66-73 C.E. had left the population and countryside in ruins. The Temple of Jerusalem had been destroyed, tens of thousands of Jews in Jerusalem had been killed, and most of the remainder were driven from the city by the future Emperor Titus.

Emperor Hadrian ascended to the throne in 118 C.E. in the aftermath of continuing Jewish unrest in Egypt, Cyrene and Cyprus. However, he sought to mollify the Jews of Judea and Jerusalem, where a substantial Jewish population had now resettled. He even seems to have ordered the rebuilding of the Temple of Jerusalem, though on terms that outraged pious Jews, in that it was to be constructed on a new site.

A potential rebellion was averted through the intervention of Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah (Gen. R. 64). Secret anti-Rome factions, however, began to prepare for war, reportedly stockpiling weapons and converting caves in the mountains into hidden fortifications, connected by subterranean passages.

The situation came to a head when Hadrian forbade the circumcision of infants, which the Jews found intolerable.[2] The fact that nearly every living Jew in Judea must have had relatives who had been killed in the earlier revolt added fuel to the revolutionary fire, as did the Roman policy of insisting that pagan sacrifice be offered in the holy city. Although Bar Kokhba himself is not yet heard from, it is likely that he was already one of the organizers of this movement. [3]

Bar Kokhba’s Israel

There is little historical information about the early stages of the revolt. It apparently began in 132, when the rebuilding of Jerusalem as a Roman city damaged the supposed tomb of Solomon. According to the ancient historian Cassius Dio, (Roman history 69.13:1-2):

Soon, the whole of Judaea had been stirred up, and the Jews everywhere were showing signs of disturbance, were gathering together, and giving evidence of great hostility to the Romans, partly by secret and partly by open acts; many others, too, from other peoples, were joining them from eagerness for profit, in fact one might almost say that the whole world was being stirred up by this business.

In this situation Simon ben Kosiba emerged as a decisive and effective military and political leader. His surviving letters make it clear that he was in a position of authority among the revolutionary forces by April 132 until early November 135.

Israel’s Messiah?

According to Eusebius of Ceasaria (c.260-c.340), Bar Kokhba claimed to have been sent to the Jews from heaven (Church History 4.6.2). However, Simon’s own letters show him to be of a pragmatic military and political mind. There is indeed evidence, however, that the Talmudic sage Rabbi Akiva considered him to be the deliverer. Akiva reportedly said of him, "This is the King Messiah" (Yer. Ta'anit iv. 68d).

On some of his coins and in his letters, Bar Kokhba calls himself "Prince" (Nasi), a word that some believe had strong messianic connotations. However, it should be noted that presidents of the Sanhedrin were also called Nasi, with no hint of messianic allusion. The name Bar Kochba itself has messianic connotations, however. It could be that Bar Kokhba accepted the messianic role, conceived as essentially political, even if he did not think of it in apocalyptic terms. The common Jewish expectation, it should be remembered, was that the Messiah was a deliverer from foreign rule, indeed sent by God, but not a supernatural being.

Akiva was joined by at least two other prominent rabbis—Gershom and Aha—in recognizing Bar Kokhba as the Messiah. However, others disagreed, having already soured on opposition to Rome or wanting more certain confirmation from God before supporting any messianic candidate.

The new Jewish state minted its own coins and was called "Israel." Although Bar Kokhba’s forces apparently never succeeded in taking Jerusalem, their control of Judea was extensive, as evidenced by the fact that coins minted by the new Jewish state have been found throughout the rest of the area. Legal documents show that former Roman imperial lands were confiscated by the state of Israel and leased to Jews for farming.

Roman reaction

As a result of Bar Kokhba’s success, Hadrian was forced to send several of his most able commanders to deal with the rebellion, among them Julius Severus, had previously been governor of Britain, Publicius Marcellus end Haterius Nepos, the governors of Syria and Arabia, respectively. Hadrian himself eventually arrived on the scene as well.

The Romans committed no less than 12 legions, amounting to one third to one half of the entire Roman army, to re-conquer this now independent state. Outnumbered and taking heavy casualties, but confident nevertheless of their long-term military superiority, the Romans refused to engage in an open battle and instead adopted a scorched earth policy which decimated the Judean populace, slowly grinding away at the will of the Judeans to sustain the war.

Jewish sources report terrible atrocities by the Romans, including children being wrapped in Torah scrolls and burned alive (Bab. Talmud, Gittin 57a-58b). The absolute devotion of the rebels to their leader and his cause resulted in very few of them surrendering, and in the end very few survived.

Some Jews began to regret the rebellion. The fourth century Christian writer Hieronymus reported that the “citizens of Judea came to such distress that they, together with their wives, children, gold and silver remained in underground tunnels and in the deepest caves.” (Commentary on Isaiah 2.15). His claim has been confirmed by archaeologists who found human remains, cooking utensils, and letters it digs at caves at Wadi Murabba at and Nahal Hever.

A fallen star

Eventually the Romans succeeded in taking one after another of the Jewish strongholds. Bar Kokhba took his final stand at Bethar, possibly located a short march southwest of Jerusalem.[4] The siege continued until the winter of 135-136. When the fortress was finally taken, Bar Kokhba’s body was among the corpses. Most of the dead succumbed to disease and starvation, not battle wounds. Hadrian reportedly stated, upon being presented with the would-be Messiah’s head: “If his God had not slain him, who could have overcome him?”

According to Jewish tradition, Bethar fell on July 25, 136. However, the fact that Hadrian assumed the title of Conqueror late in 135 leads historians to assume an earlier date of November or December of that year.[5]

Cassius Dio stated 580,000 Jews were killed in the war against Bar Kokhba, with 50 fortified towns and 985 villages being razed. Jerusalem also was destroyed, and the new Roman city, Aelia Capitolina, was built in its place, this time with no accommodation to Jewish sensibilities whatsoever.

Yet so costly was the Roman victory over Bar Kokhba’s state that Hadrian, when reporting to the Roman Senate, did not see fit to begin with the customary greeting "I and my army are well," and is the only Roman general known to have refused to celebrate his victory with a triumphal entrance into his capital.

In the aftermath of the war, Hadrian consolidated the older political units of Judea, Galilee, and Samaria into the new province of Syria Palaestina (Palestine), a name that has since passed into most European languages as well as into Arabic. The new provincial designation, derived from the ancient sea-faring Philistine people who occupied the coastal plain around the first millennium B.C.E.

Legacy

Bar Kokhba’s defeat was followed by a persecution of Jews by Hadrian, who now saw the religion itself as incompatible with Roman order. Prisoners from the war were sold as slaves and Jews were forbidden to teach the Mosaic law or to own Torah scrolls. The Palestinian center of Jewish learning at Jamnia came to an end, resulting in the ascendancy of the Babylonian Talmud, rather than the Palestinian version, in later Jewish tradition.

In Jerusalem, a temple to Jupiter was built on the site of the Temple of Yahweh, and a sanctuary devoted to goddess Aphrodite was built where the Christians—-viewed by Hadrian as a Jewish sect—venerated the tomb of Jesus. Jews were banned both from living in and even visiting Jerusalem. Rabbi Akiva violated this law, becoming a martyr for his act, along with nine of his colleagues.

In the aftermath, rabbinical tradition turned strongly against messianic claims in general, an attitude that persists to this day. Talmudic sources began to call the Messiah of Rabbi Akiva “bar Kozeva',” meaning “son of lies.”[6]

Judaism as a political force suffered a defeat from which it would not recover until the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948. Bar Kokhba became a hero among some of the Zionists, and is remembered by many during the Israeli holiday of Lag BaOmer, which had previously been associated with Akiva and his colleague Simon Ben Yochai.

Notes

- ↑ Jesus of Nazareth would be recognized as more successful than Bar Kokhba in Christian tradition, as well as in Islam, which also accepts Jesus as the Messiah. However, from the Jewish perspective, Jesus was not a successful messianic claimant, for he did not restore an independent Jewish state.

- ↑ Jews are commanded to circumcise their son on the eighth day after birth. Hadrian's edict also banned castration and did not affect voluntary circumcision by legally adult males.

- ↑ Bar Kokba Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ Some hold that Bethar must have been in Samaritan territory, basing their opinion on a Talmudic tradition (Yer. Ta'anit 68d; Lam. R. to chap. ii. 2) that blames the fall of Bethar on Samaritan treachery.

- ↑ A letter from Bar Kokhba himself dated Oct/November 135 is accepted as evidence that Bethar could not have fallen earlier than this.

- ↑ Akiva himself remains highly revered in Jewish tradition and liturgy, however.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eck, W. "The Bar Kokhba Revolt: the Roman point of view." Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999): 76ff.

- Goodblatt, David, Avital Pinnick and Daniel Schwartz. Historical Perspectives: From the Hasmoneans to the Bar Kohkba Revolt In Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Boston: Brill, 2001. ISBN 9004120076

- Marks, Richard. The Image of Bar Kokhba in Traditional Jewish Literature: False Messiah and National Hero. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994. ISBN 027100939X

- Reznick, Leibel. The Mystery of Bar Kokhba: Northvale: J.Aronson, 1996. ISBN 1568215029

- Schafer, Peter. The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered. Tubingen: Mohr, 2003. ISBN 3161480767

- Ussishkin, David. "Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold," Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archeology (of Tel Aviv University), 20 (1993): 66ff.

- Yadin, Yigael. Bar Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Last Jewish Revolt Against Imperial Rome. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971. ISBN 0297003453

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

- The Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132-135 C.E.) Shira Schoenberg. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.