Samaritan

Samaritans today are both a religious and an ethnic group located in the Palestinian territory and Israel. Ethnically, they are descendents of the inhabitants of ancient Samaria, the center of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Religiously, they hold to a tradition based on the ancient Israelite religion; but they reject normative Judaism's Jerusalem-centered tradition as well as its scriptures, except for the Pentateuch. The center of Samaritan worship is Mount Gerizim, not Jerusalem. The Samaritans believe that Judaism has strayed from the original teachings of Moses by rejecting Mt. Gerizim, developing a Jerusalem-centered theology, and by adopting foreign religious influences during the Babylonian exile. Conversely, Samaritans were rejected by orthodox Jews in the Hebrew Bible because of their mixed blood, their insistence on Mt. Gerizim as the true authorized shrine, and because they were considered political enemies of Judah. Both Samaritans and Jews accept the Torah, or first five books in the Bible, although there are differences between the Samaritan and Jewish versions.

In the New Testament, Samaritans were despised by the Judean Jews; however, Jesus used the parable of the "Good Samaritan" to dramatize the importance of ethics versus religious formalism. Samaritans thrived at times during both the intertestamental period (fifth through first centuries B.C.E.) and the early Common Era, but have faced severe persecution as well, nearly becoming extinct in the early twentieth century. In 2006, there were less than 700 Samaritans in the world, most living near the city of Nablus in the West Bank, and in the city of Holon near Tel Aviv. The Samaritans consider themselves to be the remnant of the "lost" ten tribes of Israel. They speak either Modern Hebrew or Palestinian Arabic as their mother language. For liturgical purposes, Samaritan Hebrew and Samaritan Aramaic are used.

History

Origins

The exact historical origins of the Samaritans are controversial. The Samaritans claim that the split between Jews and Samaritan-Israelites originated when the "false" high priest Eli (spiritual father of the Biblical judge Samuel) usurped the priestly office from its occupant, Uzzi, and abandoned Gerizim to establish a rival shrine at Shiloh. Eli then prevented southern pilgrims from Judah and Benjamin from attending the Gerizim shrine. Eli also fashioned a duplicate of the Ark of the Covenant, and it was this replica that eventually made its way to the Judahite sanctuary in Jerusalem. According to the Biblical account, Eli's protégé, Samuel, later anointed David, a Judahite, as the first king of the supposedly united kingdom of Judah/Israel. The Biblical view that the kings of Judah, descended from David, represent the true sacred kingship is thus challenged by the Samaritan history, in which an allegedly false high priest originally anointed the kings of Judah, and their conviction that the sacred sanctuary of the God of Israel was supposed to be located at Gerizim, not Jerusalem.

The Samaritans see themselves as the descendants of Israelites of the Northern Kingdom who remained in Israel after the citizens of these nations were forced into exile as a result of the Assyrian invasion of 722 B.C.E. and the Babylonian campaigns culminating in 586 B.C.E., respectively. The Samaritans believe that they introduced none of the Babylonian religious tendencies that influenced the Jews during this time such as the fascination with angelic beings evidenced in the Book of Ezekiel and the apocryphal Book of Enoch, the introduction of pessimistic wisdom literature such as the Books of Job and Ecclesiastes, the sensualistic poetry of the Song of Solomon, and the inclusion of the Zoroastrian concept of a primordial struggle between God and his cosmic adversary (Satan). Samaritans also reject post-exilic Jewish holidays such as Purim and Hanukkah. As mentioned, the Samaritans believe that even before the exile, the Southern Kingdom of Judah fell into serious error by insisting that God be worshiped at the Temple of Jerusalem and denying the validity of the northern shrine at Mt. Gerizim (see map inset).

The Jews, on the other hand, believe that Jerusalem alone was the legitimate center of worship of the God of Israel, and the Samaritans lost their standing as "true" Israelites by engaging in intermarriage and adopting pagan attitudes into their faith after the Assyrian and Babylonian empires conquered Israel and Judah. A genetic study (Shen et al. 2004) validates both origin theories, concluding that contemporary Samaritans indeed descend from the Israelites, while mitochondrial DNA analysis shows descent from Assyrians and other foreign women.

Historically, the Assyrians and Babylonians forced many of the inhabitants of Israel and Judah into exile and imported non-Israelite settlers as colonists. How many Israelites remained in the land is debated, as is the question of their faithfulness to the Israelite religious tradition of strict monotheism. A theory gaining prominence among scholars holds that the conquerors deported only the middle and upper classes of the citizens, mostly town-dwellers, replacing these groups with settlers from other parts of the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. The lower classes and the settlers intermarried and merged into one community. Later, the descendants of the Jews exiled to Babylon were permitted to return, and many did. These upper class Jews had developed an increasingly exclusivist theology and refused to recognize the descendants of the non-exiles, due to their intermarriage with non-Israelite settlers, regardless of their religious beliefs.

Another element in the Jewish rejection of the native group was the issue of the Temple of Jerusalem. In the days of the Judges and Kings, the Israelite God was worshiped in various "high places" and shrines. However, later, after the Temple was built in Jerusalem, a movement to centralize the religious tradition emerged. In the Bible, the Northern Kingdom of Israel strongly resisted this attempt at centralization, but those Jews returning from exile adamantly upheld the centrality of the Temple of Jerusalem, and insisted that those who had intermarried must put away their foreign wives (Ezra 10:9-11).

Gerizim and Shechem in Scripture

The Samaritans understand Mt. Gerizim to be the place where God chose to establish "His Name" (Deut 12:5). Deuteronomy 11:29 states:

When the Lord your God has brought you into the land you are entering to possess, you are to proclaim on Mount Gerizim the blessings, and on Mount Ebal the curses.

However, after the split between Judah and Israel the sacred nature of Mt. Gerizim became a bone of contention. Biblical tradition during the latter part of the period of the Divided Kingdoms forbade offering sacrifice to God outside of the Temple in Jerusalem. The Israelite shrines at Bethel, Dan, and other "high places"—such as Mt. Gerizim—were condemned by the prophets and the authors of other Biblical books such as Kings and Chronicles.

Archaeological excavations at Mt. Gerizim suggest that a Samaritan temple was built there around 330 B.C.E., and when Alexander the Great (356-323) was in the region, it is said that he visited Samaria and not Jerusalem.

The New Testament (John 4:7-20) records the following illustrative exchange between a Samaritan woman and Jesus of Nazareth regarding the Samaritan Temple and relations between Samaritans and Jews:

- Jesus said to her, "Will you give me a drink?" The Samaritan woman said to him, "You are a Jew and I am a Samaritan woman. How can you ask me for a drink?"... Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, but you Jews claim that the place where we must worship is in Jerusalem.

200 B.C.E. to the Christian Era

After the coming of Alexander the Great, Samaria, like Judea, was divided between a Hellenizing faction based in its towns and a pious faction, which was led by the High Priest and based largely around Shechem and the rural areas. The Greek ruler Antiochus Epiphanes was on the throne of Syria from 175 to 164 B.C.E.. His determined policy was to Hellenize his entire kingdom, which included both Judea and Samaria.

A major obstacle to Antiochus' ambition was the fidelity of the Jews to their historic religion. The military revolt of the Maccabees against Antiochus' program exacerbated the schism between Jews and Samaritans, as the Samaritans did not join in the rebellion. The degree of Samaritan cooperation with the Greeks is a matter of controversy.

- Josephus Book 12, Chapter 5 quotes the Samaritans as saying:

- We therefore beseech thee, our benefactor and savior, to give order to Apolonius, the governor of this part of the country, and to Nicanor, the procurator of thy affairs, to give us no disturbances, nor to lay to our charge what the Jews are accused for, since we are aliens from their nation and from their customs, but let our temple which at present hath no name at all, be named the Temple of Jupiter Hellenius.

- II Maccabees 6:1-2 says:

- Shortly afterwards, the king sent Gerontes the Athenian to force the Jews to violate their ancestral customs and live no longer by the laws of God; and to profane the Temple in Jerusalem and dedicate it to Olympian Zeus, and the one on Mount Gerizim to Zeus, Patron of Strangers, as the inhabitants of the latter place had requested.

Both of these sources are Jewish. The "request" of the Samaritans to rename their temple was likely made under duress. However, the Samaritans clearly did not resist nearly as strenuously as did the Jews. In any case, the schism between the Jews and Samaritans was now final. After the victory of the Maccabees, this incarnation of the Samaritan Temple at Mount Gerizim was destroyed by the Jewish Hasmonean ruler John Hyracanus around 128 B.C.E., having existed about 200 years. Only a few stone remnants of it exist today.

Samaritans also fared badly under the early part of Roman rule. In the time of Jesus, they were a despised and economically depressed people.

The Common Era

In the first part of the Common Era, Samaria was incorporated into the Roman province of Judea, and in the second century a period of Samaritan revival began. The Temple of Gerizim was rebuilt after the Jewish Bar Kochba revolt, around 135 C.E. The high priest Baba Rabba set much of the current Samaritan liturgy in the fourth century. There were also some Samaritans in the Persian Empire, where they served in the Sassanid army.

Later, under the Byzantine Emperor Zeno in the late fifth century, both Samaritans and Jews were massacred, and the Temple on Mt. Gerizim was again destroyed. In 529 C.E., led by a charismatic messianic figure named Julianus ben Sabar, the Samaritans launched a war to create their own independent state. With the help of the Ghassanid Arabs, Emperor Justinian I crushed the revolt and tens of thousands of Samaritans were killed and enslaved. The Samaritan faith was virtually outlawed thereafter by the Christian Byzantine Empire; from a population once likely in the hundreds of thousands, the Samaritan community dwindled to near extinction.

Many of the remaining Samaritans fled the country in 634 C.E., following the Muslim victory at the Battle of Yarmuk, and Samaritan communities were established in Egypt and Syria, but they did not survive into modern times. During the mid 800s C.E. Muslim zealots destroyed Samaritan and Jewish synagogues. During the tenth century relations between Muslims, Jews and Samaritans improved greatly. In the 1300s the Mamluks came to power and they plundered Samaritan religious sites, and turned their shrines into mosques. Many Samaritans converted to Islam out of fear. After the Ottoman conquest, Muslim persecution of Samaritans increased again. Massacres were frequent. According to Samaritan tradition, in 1624 C.E., the last Samaritan high priest of the line of Eleazar son of Aaron died without issue, but descendants of Aaron's other son, Ithamar, remained and took over the office.

By the 1830s only a small group of Samaritans in Shechem remained extant. The local Arab population believed that Samaritans were "atheists" and "against Islam," and they threatened to murder the entire Samaritan community. The Samaritans turned to the Jewish community for help and Jewish entreaties to treat the Samaritans with respect were eventually heeded.

Persecution and assimilation reduced their numbers drastically. In 1919, an illustrated National Geographic report on the community stated that their numbers were less than 150.

Modern Times

According to the Samaritan community's Educational Guide the Samaritans now number around 650, divided about equally between their modern homes in the settlement of Kiryat Luza on their sacred Mt. Gerizim, and the Israeli town of Holon, just outside of Tel Aviv.

Until the 1980s, most of the Samaritans resided in the Palestinian town of Nablus below Mt. Gerizim. They relocated to the mountain itself as a result of the first Intifada, and all that is left of their community in Nablus itself is an abandoned synagogue. But the conflict followed them. In 2001, the Israeli army set up an artillery battery on Gerizim.

Relations with the surrounding Jews and Palestinians have been mixed. In 1954, Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi created the Samaritan enclave in Holon but Israeli Samaritans today complain of being treated as "pagans and strangers" by orthodox Jews. Those living in Israel have Israeli citizenship. Samaritans in the Palestinian territories are a recognized minority and they send one representative to the Palestinian parliament. Palestinian Samaritans have been granted passports by both Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

As a small community divided between two frequently hostile neighbors, the Samaritans are generally unwilling to take sides in the conflict, fearing that whatever side they take could lead to repercussions from the other.

One of the biggest problems facing the community today is the issue of continuity. With such a small population, divided into only four families (Cohen, Tsedakah, Danfi, and Marhib) and a refusal to accept converts, there has been a history of genetic disease within the group. To counter this, Samaritans have recently agreed that men from the community may marry non-Samaritan (i.e. Jewish) women, provided that they agree to follow Samaritan religious practices.

In 2004 the Samaritan high priest, Shalom b. Amram, passed away and was replaced by Elazar b. Tsedaka. The Samaritan high priest is selected by age from the priestly family, and resides on Mount Gerizim.

Samaritan Religious Beliefs

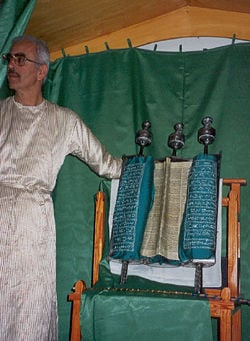

The Samaritan view of God is similar to the Jewish belief in One God, who made a covenant with the people of Israel centering on the Law of Moses. Samaritan scriptures include the Samaritan version of the Torah, the Memar Markah, the Samaritan liturgy, and Samaritan law codes and Biblical commentaries. Samaritans claim to have a very ancient version of the Torah, the Abisha Scroll, dating back to a grandson of Aaron, the brother of Moses. Scholars question the age of this scroll, which has not been scientifically dated. It is agreed that some Samaritan Torah scrolls are as old as the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint; scholars have various theories concerning the actual relationships between these three texts.

Samaritans do not accept the Old Testament books of historical writings, wisdom literature, or the prophets as sacred scripture. The Samaritan Torah differs in some respects from the Jewish Torah. The Samaritans consider several of the "judges" of ancient Israel as "kings", and their list of authentic northern kings of Israel differs considerably from the Biblical accounts in the books of Kings and Chronicles. Royal Judean figures such as David and Solomon do not play a major role in the Samaritan histories.

Samaritans believe in a Restorer, called the "Taheb", who is roughly equivalent to the Jewish Messiah. His ministry will center on Mt. Gerizim, bringing about the unification of Judah and Israel and the restoration of the true religion of Moses.

Like the Jews, Samaritans keep the Sabbath, circumcise male children, and follow strict rules regarding ritual purity. They celebrate Passover, Pentecost, Yom Kippur, and other important holidays, but not Purim or Hannukkah. The priesthood remains a central office in their faith. Samaritan lineage is patrilineal, while Jewish lineage is matrilineal. An English translation of the Samaritan Torah is pending.

Samaritans in the Gospels

The story of "The Good Samaritan" is a famous New Testament parable appearing in the Gospel of Luke (10:25-37). The parable is told by Jesus to illustrate that compassion should be for all people, and that fulfilling the spirit of the Law is more important than fulfilling the letter of the Law.

In Luke, a scholar of the Law tests Jesus by asking him what is necessary to inherit eternal life. To begin his answer, Jesus asks the lawyer what the Mosaic Law says about it. When the lawyer quotes the basic law of loving God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength and all your mind, and the parallel law of the Golden Rule, Jesus says that he has answered correctly— "Do this and you will live," he tells him.

When the lawyer then asks Jesus to tell him who his neighbor is, Jesus responds with a parable of the Good Samaritan. It tells about a traveler who was attacked, robbed, stripped, and left for dead by the side of a road. Later, a priest saw the stricken figure and avoided him, presumably in order to maintain ritual purity. Similarly, a Levite saw the man and ignored him as well. Then a Samaritan passed by, and, despite the mutual antipathy between his and the Jewish populations, immediately rendered assistance by giving him first aid and taking him to an inn to recover while promising to cover the expenses.

At the conclusion of the story, Jesus asks the lawyer, which one of these three passers-by was the stricken man's neighbor? When the lawyer responds that it was the man who helped him, Jesus responds with "Go and do the same."

This parable is one of the most famous from the New Testament and its influence is such that to be called a "Good Samaritan" in Western culture today is to be described as a generous person who is ready to provide aid to people in distress without hesitation. However, the parable, as told originally, had a significant theme of non-discrimination and interracial harmony, which is often overlooked today but greatly needed. As the Samaritan population dwindled to near-extinction, this aspect of the parable became less and less discernible: fewer and fewer people ever met or interacted with Samaritans, or even heard of them in any context other than this one.

In addition to the parable of the Good Samaritan found in the Gospel of Luke (Chapter 10), there are a few other references to Samaritans in the New Testament. In the Gospel of John, the Samaritan Woman of Sychar provides water for Jesus to drink and later testifies to him. Correspondingly, the Samaritans of Sychar offer Jesus hospitality, and many come to believe in him (John 4:39-40).

However, the Gospels are not uniformly positive towards the Samaritans, which is shown in the Gospel of Matthew (10:5-6), where Jesus tells his disciples: "Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel." Moreover, the Gospel of Matthew does not report the parable of the Good Samaritan or any story of Jesus entering a Samaritan town and speaking to Samaritans. Therefore, even in the Gospels one can detect a degree of ambivalence towards the Samaritans that has characterized their relationship with the Jews to this day.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Robert T., and Terry Giles. The Keepers: An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritans. Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 978-1565635197

- Montgomery, James Alan. The Samaritans, the Earliest Jewish Sect; their History, Theology, and Literature. BiblioBazaar, 2009. ISBN 978-1113465689

- Pummer, Reinhard. The Samaritans: A Profile. Eerdmans, 2016. ISBN 978-0802867681

- Tsedaka, Benyamim, and Sharon Sullivan (eds.). The Israelite Samaritan Version of the Torah: First English Translation Compared with the Masoretic Version. Eerdmans, 2013. ISBN 978-0802865199

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Introduction to James A Montgomery’s Samaritans the earliest Jewish sect their history, theology, and literature

- Samaritan alphabet

- 1911 Jewish Encyclopedia, "Samaritans"

- Samaritan high priests

- Guards of Mount Grizim

- Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations from Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation, by Peidong Shen, et al., in Human Mutation vol. 24 (2004), pp. 248-260

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.