| Bees | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Osmia ribifloris

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Andrenidae |

Bee is any member of a group of about 20,000 known species of winged insects of the superfamily Apoidea of the order Hymenoptera, an order that includes the closely related ants and wasps. Although bees are often defined as all the insects comprising Apoidea, they now are generally seen as a monophyletic lineage within this superfamily comprising the unranked taxon name Anthophila, with the "sphecoid" wasps being the other traditionally recognized lineage in Apoidea.

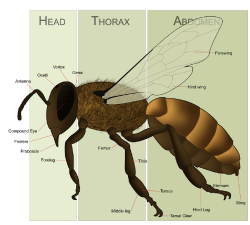

Bees are characterized by sucking and chewing mouth parts, large hind feet, and hair-like extensions on the head and thorax. Almost all extant species of bees subsist on nectar and pollen, with nectar serving as a carbohydrate and energy source, and pollen as a source of protein and other nutrients. Bees convert nectar to honey in their digestive tract. Most pollen is used as food for larvae.

Bees are found on every continent except Antarctica, in every habitat on the planet that contains flowering dicotyledons. Most are solitary, but there are also many that are social insects.

Bees reveal the harmony in nature. For one, almost all bees are obligately dependent on flowers, in order to receive pollen and nectar, and the flowering plants are dependent on the bees for pollination. In advancing their own survival and reproduction, each benefits the other. This also fits with the view of Margulis and Sagan (1986) that "Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking"âthat is, by cooperation.

Some bees, notably the eusocial bees, also exhibit altruism. Altruistic behavior increases the survival or fitness of others, but decreases that of the actor. A honeybee, for example, will sting a potential predator. In the process, the honeybee will die, but the colony is protected. Likewise, the worker bees do not reproduce, but sacrifice themselves for the sake of the queen and offspring and the colony.

Despite the honeybee's painful sting and the typical attitude towards insects as pests, people generally hold bees in high regard. This is most likely due to their usefulness as pollinators and as producers of honey, their social nature, and their diligence. Although a honeybee sting can be deadly to those with allergies, virtually all other bee species are non-aggressive if undisturbed, and many cannot sting at all. Bees are used to advertise many products, particularly honey and foods made with honey, thus being one of the few insects used on advertisements.

Introduction

Bees have antennae almost universally made up of thirteen segments in males and twelve in females, as is typical for the superfamily. Bees all have two pairs of wings, the hind pair being the smaller of the two; in a very few species, one sex or caste has relatively short wings that make flight difficult or impossible, but none are wingless.

Unlike wasps, which can be carnivorous, almost all bees are dependent on flowers for food, and are adapted for feeding on nectar and pollen. Bees typically have a long proboscis (a complex "tongue") that enables them to obtain the nectar from flowers. There are a few species that can feed on secretions from other insects, such as aphids.

The smallest bee is the dwarf bee (Trigona minima) and it is about 2.1 mm (5/64") long. The largest bee in the world is Megachile pluto, which can grow to a size of 39 mm (1.5"). The most common type of bee in the Northern Hemisphere are the many species of Halictidae, or sweat bees, though they are small and often mistaken for wasps or flies.

The most well-known bee species is the Western honeybee, which, as its name suggests, produces honey, as do a few other types of bee. Human management of this species is known as beekeeping or apiculture.

Yellowjackets and hornets, especially when encountered as flying pests, are often mis-characterized as "bees."

Pollination

Bees play an important role in pollinating flowering plants, and are the major type of pollinators in ecosystems that contain flowering plants. Bees may focus on gathering nectar or on gathering pollen, depending on their greater need at the time, especially in social species. Bees gathering nectar may accomplish pollination, but bees that are deliberately gathering pollen are more efficient pollinators.

Bees are extremely important as pollinators in agriculture, especially the domesticated Western honeybee. It is estimated that one third of the human food supply depends on insect pollination, most of this accomplished by bees. Contract pollination has overtaken the role of honey production for beekeepers in many countries, with the honeybees being rented to farmers for pollination purposes.

Monoculture and pollinator decline (of many bee species) have increasingly caused honeybee keepers to become migratory so that bees can be concentrated in areas of pollination needed at the appropriate season. Recently, many such migratory beekeepers have experienced substantial losses, prompting the announcement of investigation into the phenomenon, dubbed "Colony Collapse Disorder," amid great concern over the nature and extent of the losses. Many other species of bees such as mason bees are increasingly cultured and used to meet the agricultural pollination need. Many bees used in pollination survive in refuge in wild areas away from agricultural spraying, only to be poisoned in massive spray programs for mosquitoes, gypsy moths, or other insect pests.

Bees also play a major, though not always understood, role in providing food for birds and wildlife.

Most bees are fuzzy and carry an electrostatic charge, thus aiding in the adherence of pollen. Female bees periodically stop foraging and groom themselves to pack the pollen into the scopa, a pollen-carrying modification of dense hairs, which is on the legs in most bees, and on the ventral abdomen on others, and modified into specialized pollen baskets on the legs of honeybees and their relatives.

Many bees are opportunistic foragers, and will gather pollen from a variety of plants, but many others are oligolectic, gathering pollen from only one or a few types of plants. No known bees are nectar specialists; many oligolectic bees will visit multiple plants for nectar. There are no bees that are known to visit only one plant for nectar while also gathering pollen from many different sources. A small number of plants produce nutritious floral oils rather than pollen, which are gathered and used by oligolectic bees. Specialist pollinators also include these bee species that gather floral oils instead of pollen, and male orchid bees, which gather aromatic compounds from orchids (one of the only cases where male bees are effective pollinators).

In a very few cases only one species of bee can effectively pollinate a plant species, and some plants are endangered at least in part because their pollinator is dying off. There is, however, a pronounced tendency for oligolectic bees to be associated with common, widespread plants, which are visited by multiple pollinators (e.g., there are some 40 oligoleges associated with creosotebush in the U.S. desert southwest (Hurd and Linsley 1975), and a similar pattern is seen in sunflowers, asters, and mesquite).

One small subgroup of stingless bees (called "vulture bees") is specialized to feed on carrion, and these are the only bees that do not use plant products as food.

Pollen and nectar are usually combined together to form a "provision mass," which is often soupy, but can be firm. It is formed into various shapes (typically spheroid), and stored in a small chamber (a "cell"), with the egg deposited on the mass. The cell is typically sealed after the egg is laid, and the adult and larva never interact directly (a system called "mass provisioning").

Visiting flowers is a dangerous occupation with high mortality rates. Many assassin bugs and crab spiders hide in flowers to capture unwary bees. Others are lost to birds in flight. Insecticides used on blooming plants can kill large numbers of bees, both by direct poisoning and by contamination of their food supply. A honeybee queen may lay 2000 eggs per day during spring buildup, but she also must lay 1000 to 1500 eggs per day during the foraging season, simply to replace daily casualties.

The population value of bees depends partly on the individual efficiency of the bees, but also on the population itself. Thus, while bumblebees have been found to be about ten times more efficient pollinators on cucurbits, the total efficiency of a colony of honeybees is much greater, due to greater numbers. Likewise, during early spring orchard blossoms, bumblebee populations are limited to only a few queens, and thus are not significant pollinators of early fruit.

Eusocial and semisocial bees

Bees may be solitary or may live in various types of communities. Sociality, of several different types, is believed to have evolved separately many times within the bees.

In some species, groups of cohabiting females may be sisters, and if there is a division of labor within the group, then they are considered semisocial.

The most advanced of the social communities are eusocial colonies, found among the honeybees, bumblebees, and stingless bees. In these, in addition to a division of labor, the group consists of a mother and her daughters. The mother is considered the "queen" and the daughters are "workers."

Eusocial colonies can be primitively social or highly social. If the castes are purely behavioral alternatives, the system is considered "primitively eusocial" (similar to many paper wasps), and if the castes are morphologically discrete, then the system is "highly eusocial."

There are many more species of primitively eusocial bees than highly eusocial bees, but they have been rarely studied. The biology of most such species is almost completely unknown. Some of the species of sweat bees (family Halictidae) and bumblebees (family Bombidae) are primitively social, with the vast majority in the family Halictidae. Colonies are typically small, with a dozen or fewer workers, on average. The only physical difference between queens and workers is average size, if they differ at all. Most species have a single season colony cycle, even in the tropics, and only mated females (future queens, or "gynes") hibernate (called diapause). The colony may begin with the overwintering queen producing sterile female workers and later producing sexuals (drones and new queens). A few species have long active seasons and attain colony sizes in the hundreds. The orchid bees include a number of primitively eusocial species with similar biology. Certain species of allodapine bees (relatives of carpenter bees) also have primitively eusocial colonies, with unusual levels of interaction between the adult bees and the developing brood. This is "progressive provisioning;" a larva's food is supplied gradually as it develops. This system is also seen in honeybees and some bumblebees.

Highly eusocial bees live in colonies. Each colony has a single queen, together with workers and, at certain stages in the colony cycle, drones. When humans provide a home for a colony, the structure is called a hive. A honeybee hive can contain up to 40,000 bees at their annual peak, which occurs in the spring, but usually have fewer.

Bumblebees

Bumblebees are bees of the genus Bombus in the family Apidae (Bombus terrestris, B. pratorum, et al.). They are eusocial in a manner quite similar to the eusocial Vespidae, such as hornets. The queen initiates a nest on her own (unlike queens of honeybees and stingless bees, which start nests via swarms in the company of a large worker force). Bumblebee colonies typically have from 50 to 200 bees at peak population, which occurs in mid to late summer. Nest architecture is simple, limited by the size of the nest cavity (pre-existing), and colonies are rarely perennial. Bumblebee queens sometimes seek winter safety in honeybee hives, where they are sometimes found dead in the spring by beekeepers, presumably stung to death by the honeybees. It is unknown whether any survive the winter in such an environment.

Stingless bees

Stingless bees are very diverse in behavior, but all are highly eusocial. They practice mass provisioning, complex nest architecture, and perennial colonies.

Honeybees

The true honeybees, genus Apis, have arguably the most complex social behavior among the bees. The Western (or European) honeybee, Apis mellifera, is the best known bee species and one of the best known of all insects.

Africanized honeybee

Africanized bees, also called killer bees, are a hybrid strain of Apis mellifera derived from experiments to cross European and African honeybees by Warwick Estevam Kerr. Several queen bees escaped his laboratory in South America and have spread throughout the Americas. Africanized honeybees are more defensive than European honeybees.

Solitary and communal bees

Most bee species are solitary in the sense that every female is fertile, and typically inhabits a nest she constructs herself. There are no "worker" bees for these species. Solitary bees include such familiar species as the Eastern carpenter bee (Xylocopa virginica), alfalfa leafcutter bee (Megachile rotundata), orchard mason bee (Osmia lignaria), and the hornfaced bee (Osmia cornifrons).

Solitary bees typically produce neither honey nor beeswax. They are immune from acarine and Varroa mites, but have their own unique parasites, pests, and diseases.

Solitary bees are important pollinators, and pollen is gathered for provisioning the nest with food for their brood. Often it is mixed with nectar to form a paste-like consistency. Some solitary bees have very advanced types of pollen carrying structures on their bodies. A very few species of solitary bees are being increasingly cultured for commercial pollination.

Solitary bees are often oligoleges, in that they only gather pollen from one or a few species/genera of plants (unlike honeybees and bumblebees, which are generalists).

Solitary bees create nests in hollow reeds or twigs, holes in wood, or, most commonly, in tunnels in the ground. The female typically creates a compartment (a "cell") with an egg and some provisions for the resulting larva, then seals it off. A nest may consist of numerous cells. When the nest is in wood, usually the last (those closer to the entrance) contain eggs that will become males. The adult does not provide care for the brood once the egg is laid, and usually dies after making one or more nests. The males typically emerge first and are ready for mating when the females emerge. Providing nest boxes for solitary bees is increasingly popular for gardeners. Solitary bees are either stingless or very unlikely to sting (only in self defense, if ever).

While solitary females each make individual nests, some species are gregarious, preferring to make nests near others of the same species, giving the appearance to the casual observer that they are social. Large groups of solitary bee nests are called "aggregations," to distinguish them from colonies.

In some species, multiple females share a common nest, but each makes and provisions her own cells independently. This type of group is called "communal" and is not uncommon. The primary advantage appears to be that a nest entrance is easier to defend from predators and parasites when there are multiple females using that same entrance on a regular basis.

Cleptoparasitic bees

Cleptoparasitic bees, commonly called "cuckoo bees" because their behavior is similar to cuckoo birds, occur in several bee families, though the name is technically best applied to the apid subfamily Nomadinae. Females of these bees lack pollen collecting structures (the scopa) and do not construct their own nests. They typically enter the nests of pollen collecting species, and lay their eggs in cells provisioned by the host bee. When the cuckoo bee larva hatches it consumes the host larva's pollen ball, and if the female cleptoparasite has not already done so, kills and eats the host larva. In a few cases where the hosts are social species, the cleptoparasite remains in the host nest and lays many eggs, sometimes even killing the host queen and replacing her.

Many cleptoparasitic bees are closely related to, and resemble, their hosts in looks and size, (i.e., the Bombus subgenus Psithyrus, which are parasitic bumblebees that infiltrate nests of species in other subgenera of Bombus). This common pattern gave rise to the ecological principle known as "Emery's Rule," that social parasites among insects tend to be parasites of species or genera to which they are closely related. Others parasitize bees in different families, like Townsendiella, a nomadine apid, one species of which is a cleptoparasite of the melittid genus Hesperapis, while the other species in the same genus attack halictid bees.

"Nocturnal" bees

Four bee families (Andrenidae, Colletidae, Halictidae, and Apidae) contain some species that are crepuscular; that is, active during twilight (these may be either the "vespertine" or "matinal" type, denoting animals active in the evening or morning respectively). These bees have greatly enlarged ocelli, which are extremely sensitive to light and dark, though incapable of forming images. Many are pollinators of flowers that themselves are crepuscular, such as evening primroses, and some live in desert habitats where daytime temperatures are extremely high.

Evolution

Bees, like ants, are considered essentially to be a highly specialized form of wasp. The ancestors of bees are held to have been wasps in the family Crabronidae, and therefore predators of other insects. The switch from insect prey to pollen may have resulted from the consumption of prey insects that were flower visitors and were partially covered with pollen when they were fed to the wasp larvae. A similar evolutionary scenario from predatory ancestors to pollen collectors is considered to have occurred within the vespoid wasps, involving the group known as "pollen wasps."

The oldest definitive bee fossil is Cretotrigona prisca in New Jersey amber and of Cretaceous age. The recently reported "bee" fossil, of the genus Melittosphex, is in fact a wasp stem-group to Anthophila but cannot be considered an actual bee, as it lacks definitive bee traits and no information is available on whether or not it fed its larvae pollen.

The earliest animal-pollinated flowers were believed to have been pollinated by insects such as beetles, so the syndrome of insect pollination was well established before bees first appeared. The novelty is that bees are specialized as pollination agents, with behavioral and physical modifications that specifically enhance pollination, and are much more efficient at the task than beetles, flies, butterflies, pollen wasps, or any other pollinating insect. The appearance of such floral specialists is believed to have driven the adaptive radiation of the angiosperms, and, in turn, the bees themselves.

Gallery

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grimaldi, D., and M. S. Engel. 2005. Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521821495

- Hurd, P. D., and E. G. Linsley. 1975. The principal Larrea bees of the southwestern United States. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 193: 1-74.

- Margulis L., and D. Sagan. 1986. Microcosmos. New York: Summit Books. ISBN 0671441698

- Michener, C. D. 2000. The Bees of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801861330.

- Wilson, B. 2004. The Hive: The Story Of The Honeybee. London: John Murray. ISBN 0719565987

External links

All links retrieved September 26, 2023.

- Apoidea Images, identification guides, and maps of bees.

- Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society (UK).

- Carl Hayden Bee Research Center.

- Scientists identify the oldest known bee, a 100 million-year-old specimen preserved in amber.

- Bees, Hornets, and Wasps of the World

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.