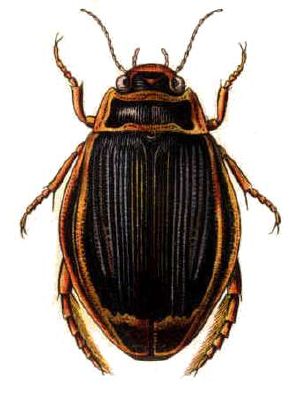

Beetle

| Beetle | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Suborders | ||||||||||||||

|

Adephaga |

Beetles are the most diverse group of insects. Their order, Coleoptera (meaning "sheathed wing"), has more species in it than any other order in the entire animal kingdom. Nearly half of all described insect species are classified as beetles, and overall there are about 400,000 known species of beetles—or about one-quarter of all named species in the plant and animal kingdoms. In addition, new species are regularly discovered. Estimates put the total number of beetle species—described and undescribed—at between 5 and 8 million.

The vast numbers of beetles led to the famous quip, perhaps apocryphal, from British geneticist J. B. S. Haldane, who, when asked what one could conclude as to the nature of God from a study of his creation, replied: "An inordinate fondness for beetles" (Gould 1996). Haldane himself was a noted atheist and this quote reflects not only the vast numbers of beetles but also Haldane's skeptical perspective on natural theology.

Beetles can be found in almost all habitats, but are not known to occur in the sea or in the polar regions. They have a major impact on the ecosystem in three ways: feeding on plants and fungi, breaking down animal and plant debris, and eating other invertebrates. Certain species can be agricultural pests, for example the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata), while other species are important controls of agricultural pests, for example the ladybirds (family Coccinellidae) consume aphids, fruit flies, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects that damage crops.

The study of beetles is called coleopterology; its practitioners are coleopterists. There is a thriving industry in the collection of wild caught species by amateur and professional collectors.

Anatomy

The anatomy of beetles is quite uniform. Beetles are generally characterized by a particularly hard exoskeleton, and the hard wing-cases (elytra) that tend to cover the hind part of the body and protect the second wings, the alae. The elytra are not used in flying, but generally must be raised in order to move the hind wings. In some cases, the ability to fly has been lost, characteristically in families such as Carabidae (ground beetles) and Curculionidae (snout beetles and true weevils). After landing, the hind wings are folded below the elytra.

In a few families, both the ability to fly and the wing-cases are absent, with the best known example being the "glowworms" of the family Phengodidae, in which the females are larviform throughout their lives.

The bodies of beetles are divided into three sections, the head, the thorax, and the abdomen, and these in themselves may be composed of several further segments.

The eyes are compound, and may display some remarkable adaptability, as in the case of the Whirligig beetles (family Gyrinidae), in which the eyes are split to allow a view both above and below the waterline. The dorsal appendage aids the beetle in stalking prey.

Like all insects, antennae and legs are both jointed.

Oxygen is taken in via a tracheal system: this takes air in through a series of tubes along the body, which is then taken into increasingly finer fibers. Pumping movements of the body force the air through the system. Beetles have hemolymph instead of blood, and the open circulatory system of the beetle is powered by a tube-like heart attached to the top inside of the thorax.

Development

Beetles are endopterygotes—a superorder of insects of the subclass Pterygota that go through distinctive larval, pupal, and adult stages, or complete metamorphosis. The larva of a beetle is often called a grub and represents the principal feeding stage of the life cycle.

The eggs of beetles are minute, but may be brightly colored. They are laid in clumps and there may be from several dozen to several thousand eggs laid by a single female.

Once the egg hatches, the larvae tend to feed voraciously, whether out in the open such as with ladybird larvae, or within plants such as with leaf beetle larvae.

As with lepidoptera, beetle larvae pupate for a period, and from the pupa emerges a fully formed beetle or imago.

In some cases, there are several transitory larvae stages; this is known as hypermetamorphosis. Examples include the blister beetles (family Meloidae).

The larval period of beetles varies between species, but can be as long as several years. Adults have an extremely variable lifespan of weeks to years.

Reproduction and parental care

Beetles may display some intricate behavior when mating. Smell is thought to be important in the location of a mate.

Conflict can play a part in the mating rituals, for example, in species such as burying beetles (genus Nicrophorus) where localized conflicts between males and females rage until only one of each is left, thus ensuring reproduction by the strongest and fittest. Many beetles are territorial and will fiercely defend their small patch of territory from intruding males.

Pairing is generally short, but in some cases will last for several hours. During pairing, sperm cells are transferred to the female to fertilize the egg.

Parental care between species varies widely, ranging from the simple laying of eggs under a leaf to scarab beetles, which construct impressive underground structures complete with a supply of dung to house and feed their young.

There are other notable ways of caring for the eggs and young, such as those employed by leaf rollers, who bite sections of leaf causing it to curl inwards and then lay the eggs, thus protected, inside.

Diet and behavior

There are few things that a beetle somewhere will not eat. Even inorganic matter may be consumed.

Some beetles are highly specialized in their diet; for example, the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) almost entirely colonizes plants of the potato family (Solanaceae). Others are generalists, eating both plants and animals. Ground beetles (family Carabidae) and rove beetles (family Staphylinidae) are entirely carnivorous and will catch and consume small prey such as earthworms and snails.

Decaying organic matter is a primary diet for many species. This can range from dung, which is consumed by coprophagous species, such as the scarab beetles (family Scarabaeidae), to dead animals, which are eaten by necrophagous species, such as the carrion beetles (family Silphidae).

Various techniques are employed by many species for retaining both air and water supplies. For example, predaceous diving beetles (family Dytiscidae) employ a technique of retaining air, when diving, between the abdomen and the elytra.

Beetles and larvae have a variety of strategies for avoiding being eaten. Many employ simple camouflage to avoid being spotted by predators. These include the leaf beetles (family Chysomelidae) that have a green coloring very similar to their habitat on tree leaves. A number of longhorn beetles (family Cerambycidae) bear a striking resemblance to wasps, thus benefitting from a measure of protection. Large ground beetles by contrast will tend to go on the attack, using their strong mandibles to forcibly persuade a predator to seek out easier prey. Many species, including lady beetles and blister beetles, can secrete poisonous substances to make them unpalatable.

Evolutionary history and classification

Beetles entered the fossil record during the Lower Permian, about 265 million years ago.

The four extant (living) suborders of beetle are:

- Polyphaga, the largest suborder, contains more than 300,000 described species in more than 170 families, including rove beetles (Staphylinidae), scarab beetles (Scarabaeidae), blister beetles (Meloidae), stag beetles (Lucanidae), and true weevils (Curculionidae). These beetles can be identified by the cervical sclerites (hardened parts of the head used as points of attachment for muscles) absent in the other suborders.

- Adephaga contains about 10 families of predatory beetles, includes ground beetles (Carabidae), predacious diving beetles (Dytiscidae), and whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae). In these beetles, the testes are tubular and the first abdominal sternum (a plate of the exoskeleton) is divided by the hind coxae (the basal joints of the beetle's legs).

- Archostemata contains four families of mainly wood-eating beetles, including reticulated beetles (Cupedidae) and telephone-pole beetles (Micromalthidae).

- Myxophaga contains about 100 described species in four families, mostly very small, including skiff beetles (Hydroscaphidae) and minute bog beetles (Sphaeriusidae).

These suborders diverged in the Permian and Triassic. Their phylogenetic relationship is uncertain, with the most popular hypothesis being that Polyphaga and Myxophaga are most closely related, with Adephaga an outgroup to those two, and Archostemata an outgroup to the other three.

The extraordinary number of beetle species poses special problems for classification, with some families consisting of thousands of species and needing further division into subfamilies and tribes.

Impact on humans

Pests

There are several agricultural and household pests represented by the order. These include:

- The Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) is a notorious pest of potato plants. Adults mate before over-wintering deep in the soil, so that when they emerge the following spring females can lay eggs immediately once a suitable host plant has been found. As well as potatoes, hosts can be a number of plants from the potato family (Solanaceae), such as nightshade, tomato, aubergine, and capsicum. Crops are destroyed and the beetle can only be treated by employing expensive pesticides, many of which it has begun to develop immunity to.

- The elm bark beetles, Hylurgopinus rufipes, elm leaf beetle Pyrrhalta luteola. and Scolytus multistriatus (in the family Scolytidae) attack elm trees. They are important elm pests because they carry Dutch elm disease (the fungus Ophiostoma ulmi) as they move from infected breeding sites to feed on healthy elm trees. The spread of the fungus by the beetle has led to the devastastation of elm trees in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere, notably North America and Europe.

- The death watch beetle (Xestobium rufovillosum) is of some considerable importance as a pest of wooden structures in older buildings in Great Britain. It attacks hardwoods, such as oak and chestnut, and always where some fungal decay has taken or is taking place. It is thought that the actual introduction of the pest into buildings takes place at the time of construction.

- Asian long-horned beetle

- Citrus long-horned beetle

Beneficial beetles

- The larvae of lady beetles (family Coccinellidae) are often found in aphid colonies, consuming these agricultural pests. While both adult and larval lady beetles found on crops prefer aphids, they will, if aphids are scarce, use food from other sources, such as small caterpillars, young plant bugs, aphid honeydew, and plant nectar.

- Large ground beetles (family Carabidae) are predators of caterpillars and, on occasion, adult weevils, which are also significant agricultural pests. Smaller species of ground beetles attack eggs, small caterpillars, and other pest insects.

To foster and provide cover for beneficial beetles, some farmers introduce beetle banks (a strip of grass or perennials that provide habitat for insects hostile to pests).

Scarab beetles in Egyptian culture

Several species of the dung beetles, most notably the Scarabaeus sacer (often referred to as "scarab"), enjoyed a sacred status among the Egyptians, as the creature was likened to the god Khepri. Some scholars suggested that the people's practice of making mummies was inspired by the brooding process of the beetle.

Many thousands of amulets and stamp seals have been excavated that depict the scarab. In many artifacts, the scarab is depicted pushing the sun along its course in the sky. Scarab amulets were often placed over the heart of the mummified deceased. The amulets were often inscribed with a spell from the Book of the Dead which entreated the heart to, "do not stand as a witness against me."

Taxonomy

This section classifies the subgroups of the order Coleoptera (beetles) down to the level of families, following the system in Arnett and Thomas' (2001, 2002) two volume set American Beetles. A few subfamilies, tribes and synonyms are shown here where a family has been reclassified.

Order Coleoptera (beetles)

- Suborder Adephaga Schellenberg 1806

- Amphizoidae (trout-stream beetles)

- Carabidae (ground beetles)

- Cicindelinae, formerly Cicindelidae (tiger beetles)

- Paussinae, formerly Paussidae

- Dytiscidae (predacious diving beetles)

- Gyrinidae (whirligig beetles)

- Haliplidae (crawling water beetles)

- Hygrobiidae

- Noteridae (burrowing water beetles)

- Rhysodidae (wrinkled bark beetles)

- Trachypachidae (false ground beetles)

- Suborder Archostemata Kolbe 1908

- Crowsonellidae

- Cupedidae (reticulated beetles)

- Micromalthidae (telephone-pole beetles)

- Ommatidae

- Suborder Myxophaga Crowson 1955

- Hydroscaphidae (skiff beetles)

- Lepiceridae

- Sphaeriusidae (minute bog beetles) (= Microsporidae: Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 57(3): 182-184.)

- Torridincolidae

- Suborder Polyphaga

- Infraorder Bostrichiformia

- Superfamily Bostrichoidea

- Anobiidae (death watch beetles)

- Ptininae, formerly Ptinidae (spider beetles)

- Bostrichidae (horned powder-post beetles)

- Lyctinae, formerly Lyctidae (powder post beetles)

- Endecatominae, formerly Endecatomidae

- Dermestidae (skin beetles)

- Thorictinae, formerly Thorictidae

- Jacobsoniidae (Jacobson's beetles)

- Nosodendridae (wounded-tree beetles)

- Anobiidae (death watch beetles)

- Superfamily Derodontoidea

- Derodontidae (tooth-necked fungus beetles)

- Superfamily Bostrichoidea

- Infraorder Cucujiformia

- Superfamily Chrysomeloidea

- Bruchidae Latreille 1802 (pea and bean weevils)

- Cerambycidae (long-horned beetles)

- Chrysomelidae (leaf beetles)

- Cassidinae (tortoise beetles subfamily)

- Megalopodidae

- Orsodacnidae

- Superfamily Cleroidea

- Acanthocnemidae

- Chaerosomatidae

- Cleridae (checkered beetles)

- Melyridae (soft-winged flower beetles)

- Phloiophilidae

- Phycosecidae

- Prionoceridae

- Trogossitidae (bark-gnawing beetles)

- Superfamily Cucujoidea

- Alexiidae

- Biphyllidae (false skin beetles)

- Boganiidae

- Bothrideridae (dry bark beetles)

- Byturidae (fruitworm beetles)

- Cavognathidae

- Cerylonidae (minute bark beetles)

- Coccinellidae (ladybirds or lady beetles)

- Corylophidae (minute fungus beetles)

- Cryptophagidae (silken fungus beetles)

- Cucujidae (flat bark beetles)

- Discolomatidae

- Endomychidae (handsome fungus beetles)

- Merophysiinae, formerly Merophysiidae

- Erotylidae (pleasing fungus beetles)

- Helotidae

- Hobartiidae

- Kateretidae (short-winged flower beetles) (= Brachypteridae. ICZN Op. 1916, 1999).

- Laemophloeidae (lined flat bark beetles)

- Lamingtoniidae

- Languriidae (lizard beetles)

- Latridiidae (minute brown scavenger beetles)

- Monotomidae (root-eating beetles)

- Rhizophaginae, formerly Rhizophagidae

- Nitidulidae (sap-feeding beetles)

- Passandridae (parasitic flat bark beetles)

- Phalacridae (shining flower beetles)

- Phloeostichidae

- Propalticidae

- Protocucujidae

- Silvanidae (silvanid flat bark beetles)

- Smicripidae (palmetto beetles)

- Sphindidae (dry-fungus beetles)

- Superfamily Curculionoidea

- Anthribidae (fungus weevils)

- Attelabidae (tooth-nosed snout beetles)

- Belidae (primitive weevils)

- Aglycyderinae, formerly Aglycyderidae

- Oxycoryninae, formerly Oxycorynidae

- Brentidae (straight-snouted weevils)

- Apioninae, formerly Apionidae

- Caridae

- Curculionidae (snout beetles and true weevils)

- Scolytinae, formerly Scolytidae (typical bark beetles)

- Ithyceridae (New York weevils)

- Nemonychidae (pine-flower snout beetles)

- Superfamily Lymexyloidea

- Lymexylidae (ship-timber beetles)

- Superfamily Tenebrionoidea

- Aderidae (antlike leaf beetles)

- Anthicidae (antlike flower beetles)

- Archeocrypticidae

- Boridae (conifer bark beetles)

- Chalcodryidae

- Ciidae (minute tree-fungus beetles) (= Cisidae)

- Colydiidae (cylindrical bark beetles)

- Melandryidae (false darkling beetles)

- Meloidae (blister beetles)

- Monommatidae (opossum beetles)

- Mordellidae (tumbling flower beetles)

- Mycetophagidae (hairy fungus beetles)

- Mycteridae (palm and flower beetles)

- Hemipeplinae, formerly Hemipeplidae

- Oedemeridae (pollen-feeding beetles)

- Perimylopidae

- Prostomidae (jugular-horned beetles)

- Pterogeniidae

- Pyrochroidae (fire-colored beetles)

- Cononotini or Cononotidae

- Pedilinae, formerly Pedilidae

- Pythidae (dead log bark beetles)

- Rhiphiphoridae (wedge-shaped beetles)

- Salpingidae (narrow-waisted bark beetles)

- Elacatini or Elacatidae

- Inopeplinae, formerly Inopeplidae

- Scraptiidae (false flower beetles)

- Stenotrachelidae (false long-horned beetles)

- Cephaloinae, formerly Cephaloidae

- Synchroidae

- Tenebrionidae (darkling beetles)

- Alleculinae, formerly Alleculidae

- Lagriinae, formerly Lagriidae

- Nilionini or Nilionidae

- Petriini or Petriidae

- Tetratomidae (polypore fungus beetles)

- Trachelostenidae

- Trictenotomidae

- Ulodidae

- Zopheridae (ironclad beetles)

- Superfamily Chrysomeloidea

- Infraorder Elateriformia

- Superfamily Buprestoidea

- Buprestidae (metallic wood-boring beetles)

- Schizopodidae

- Superfamily Byrrhoidea

- Byrrhidae (pill beetles)

- Callirhipidae (cedar beetles)

- Chelonariidae (turtle beetles)

- Cneoglossidae

- Dryopidae (long-toed water beetles)

- Elmidae (riffle beetles)

- Eulichadidae

- Heteroceridae (variegated marsh-loving beetles)

- Limnichidae (minute marsh-loving beetles)

- Lutrochidae (robust marsh-loving beetles)

- Psephenidae (water penny beetles)

- Ptilodactylidae (toe-winged beetles)

- Superfamily Dascilloidea

- Dascillidae (soft-bodied plant beetles)

- Rhipiceridae (cicada parasite beetles)

- Superfamily Elateroidea

- Artematopodidae (soft-bodied plant beetles) = (Eurypogonidae)

- Brachypsectridae (Texas beetles)

- Cantharidae (soldier beetles)

- Cerophytidae (rare click beetles)

- Drilidae

- Elateridae (click beetles)

- Cebrioninae, formerly Cebrionidae

- Eucnemidae (false click beetles)

- Lampyridae (firefly beetles)

- Lycidae (net-winged beetles)

- Omalisidae

- Omethidae (false firefly beetles)

- Phengodidae (glowworm beetles)

- Plastoceridae

- Podabrocephalidae

- Rhinorhipidae

- Telegeusidae (long-lipped beetles)

- Throscidae (false metallic wood-boring beetles) = (Trixagidae)

- Superfamily Scirtoidea

- Clambidae (minute beetles)

- Decliniidae

- Eucinetidae (plate-thigh beetles)

- Scirtidae (marsh beetles) (= Helodidae)

- Superfamily Buprestoidea

- Infraorder Scarabaeiformia

- Superfamily Scarabaeoidea

- Belohinidae

- Bolboceratidae

- Ceratocanthidae (= Acanthoceridae)

- Diphyllostomatidae (false stag beetles)

- Geotrupidae (earth-boring dung beetles)

- Glaphyridae (bumble bee scarab beetles)

- Glaresidae (enigmatic scarab beetles)

- Hybosoridae (scavenging scarab beetles)

- Lucanidae (stag beetles)

- Ochodaeidae (sand-loving scarab beetles)

- Passalidae (bess beetles)

- Pleocomidae (rain beetles)

- Scarabaeidae (scarab beetles)

- Dynastinae, formerly Dynastidae (rhinoceros beetles)

- Trogidae (hide beetles)

- Superfamily Scarabaeoidea

- Infraorder Staphyliniformia

- Superfamily Histeroidea

- Histeridae (clown beetles)

- Sphaeritidae (false clown beetles)

- Synteliidae

- Superfamily Hydrophiloidea

- Hydrophilidae (water scavenger beetles)

- Georyssinae, formerly Georyssidae

- Epimetopidae

- Helophoridae

- Hydrophilidae (water scavenger beetles)

- Superfamily Staphylinoidea

- Agyrtidae

- Hydraenidae

- Leiodidae (round fungus beetles) = (Anisotomidae)

- Platypsyllinae or Leptinidae

- Ptiliidae (feather-winged beetles)

- Cephaloplectinae, formerly Limulodidae (horse-shoe crab beetles)

- Scydmaenidae (antlike stone beetles)

- Silphidae (carrion beetles)

- Staphylinidae (rove beetles)

- Scaphidiinae, formerly Scaphidiidae

- Pselaphinae, formerly Pselaphidae

- Superfamily Histeroidea

- Infraorder Bostrichiformia

Gallery

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnett, R. H., and M. c. Thomas. 2001. American Beetles, Volume 1: Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia. CRC Press.

- Arnett, R. H., and M. c. Thomas. 2002. American Beetles, Volume 2: Polyphaga. CRC Press.

- Beckmann, P. 2001. Living Jewels: The Natural Design of Beetles Prestel Publishing. ISBN 3791325280

- Evans, A. V., C. Bellamy, and L. C. Watson. 2000. An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0520223233

- Gould, S. J. 1993. A special fondness for beetles. Natural History 1:4-12.

- Grimaldi, D., and M. S. Engel. 2005. Evolution of the Insects Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521821495

- Harde, K. W. 1984. A Field Guide in Colour to Beetles Octopus. ISBN 0706419375.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.