Punishment is the practice of imposing something unpleasant on a person as a response to some unwanted or immoral behavior or disobedience that they have displayed. Punishment has evolved with society; starting out as a simple system of revenge by the individual, family, or tribe, it soon grew as an institution protected by governments, into a large penal and justice system. The methods of punishment have also evolved. The harshest—the death penalty—which used to involve deliberate pain and prolonged, public suffering, involving stoning, burning at the stake, hanging, drawing and quartering, and so forth evolved into attempts to be more humane, establishing the use of the electric chair and lethal injection. In many cases, physical punishment has given way to socieconomic methods, such as fines or imprisonment.

The trend in criminal punishment has been away from revenge and retribution, to a more practical, utilitarian concern for deterrence and rehabilitation. As a deterrent, punishment serves to show people norms of what is right and wrong in society. It effectively upholds the morals, values, and ethics that are important to a particular society and attempts to dissuade people from violating those important standards of society. In this sense, the goal of punishment is to deter people from engaging in activities deemed as wrong by law and the population, and to act to reform those who do violate the law.

The rise of the protection of the punished created new social movements, and evoked prison and penitentiary reform. This has also led to more rights for the punished, as the idea of punishment as retribution or revenge has large been superseded by the functions of protecting society and reforming the perpetrator.

Definitions

Punishment may be defined as "an authorized imposition of deprivations — of freedom or privacy or other goods to which the person otherwise has a right, or the imposition of special burdens — because the person has been found guilty of some criminal violation, typically (though not invariably) involving harm to the innocent."[1] Thus, punishment may involve removal of something valued or the infliction of something unpleasant or painful on the person being punished. This definition purposely separates the act of punishment from its justification and purpose.

The word "punishment" is the abstract substantiation of the verb to punish, which is recorded in English since 1340, deriving from Old French puniss-, an extended form of the stem of punir "to punish," from Latin punire "inflict a penalty on, cause pain for some offense," earlier poenire, from poena "penalty, punishment."[2]

The most common applications are in legal and similarly regulated contexts, being the infliction of some kind of pain or loss upon a person for a misdeed, namely for transgressing a law or command (including prohibitions) given by some authority (such as an educator, employer, or supervisor, public or private official). Punishment of children by parents in the home as a disciplinary measure is also a common application.

In terms of socialization, punishment is seen in the context of broken laws and taboos. Sociologists such as Emile Durkheim have suggested that without punishment, society would devolve into a state of lawlessness, anomie. The very function of the penal system is to inspire law-abiding citizens, not lawlessness. In this way, punishment reinforces the standards of acceptable behavior for socialized people.[3]

History

The progress of civilization has resulted in a vast change in both the theory and in the method of punishment. In primitive society punishment was left to the individuals wronged, or their families, and was vindictive or retributive: in quantity and quality it would bear no special relation to the character or gravity of the offense. Gradually there arose the idea of proportionate punishment, of which the characteristic type is the lex talionis—"an eye for an eye."

The second stage was punishment by individuals under the control of the state, or community. In the third stage, with the growth of law, the state took over the punitive function and provided itself with the machinery of justice for the maintenance of public order.[4] Henceforward crimes were against the state, and the exaction of punishment by the wronged individual (such as lynching) became illegal. Even at this stage the vindictive or retributive character of punishment remained, but gradually, and especially after the humanist thinkers Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, new theories begin to emerge.

Two chief trains of thought have combined in the condemnation of primitive theory and practice. On the one hand the retributive principle itself has been very largely superseded by the protective and the reformative approach. On the other, punishments involving bodily pain have become objectionable to the general sensibility of society. Consequently, corporal and capital punishment occupy a far less prominent position in societies. It began to be recognized also that stereotyped punishments, such as ones that belong to penal codes, fail to take due account of the particular condition of an offense and the character and circumstances of the offender. A fixed fine, for example, operates very unequally on rich and poor.

Modern theories date from the eighteenth century, when the humanitarian movement began to teach the dignity of the individual and to emphasize rationality and responsibility. The result was the reduction of punishment both in quantity and in severity, the improvement of the prison system, and the first attempts to study the psychology of crime and to distinguish between classes of criminals with a view to their improvement.[5]

These latter problems are the province of criminal anthropology and criminal sociology, sciences so called because they view crime as the outcome of anthropological or social conditions. The law breaker is himself a product of social evolution and cannot be regarded as solely responsible for his disposition to transgress. Habitual crime is thus to be treated as a disease. Punishment, therefore, cab be justified only in so far as it either protects society by removing temporarily or permanently one who has injured it or acting as a deterrent, or when it aims at the moral regeneration of the criminal. Thus the retributive theory of punishment with its criterion of justice as an end in itself gave place to a theory which regards punishment solely as a means to an end, utilitarian or moral, depending on whether the common advantage or the good of the criminal is sought.[6]

Types of punishments

There are different types of punishments for different crimes. Age also plays a determinant on the type of punishment that will be used. For many instances, punishment is dependent upon context.

Criminal punishment

Convicted criminals are punished according to the judgment of the court. Penalties may be physical or socieconomic in nature.

Physical punishment is usually an action that hurts a person's physical body; it can include whipping or caning, marking or branding, mutilation, capital punishment, imprisonment, deprivation of physical drives, and public humiliation.

Socioeconomic punishment affects a person economically, occupationally, or financially, but not physically. It includes fines, confiscation, demotion, suspension, or expulsion, loss of civic rights, and required hours of community service. Socioeconomic punishment relies on the assumption that the person's integration into society is valued; as someone who is well-socialized will be severely penalized and socially embarrassed by this particular action.

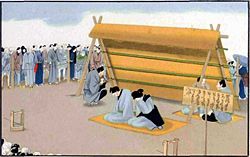

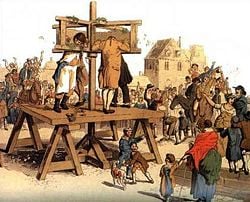

Especially if a precise punishment is imposed by regulations or specified in a formal sentence, often one or more official witnesses are prescribed, or somehow specified (such as from the faculty in a school or military officers) to see to the correct execution. A party grieved by the punished may be allowed the satisfaction of witnessing the humbled state of exposure and agony. The presence of peers, such as classmates, or an even more public venue such as a pillory on a square—in modern times even press coverage—may serve two purposes: increasing the humiliation of the punished and serving as an example to the audience.

Punishment for children

Children's punishments usually differ from punishments for adults. This is mainly because children are young and immature; therefore have not had the experiences that adults have had, and are thought to be less-knowledgeable about legal issues and law. Children who commit crimes are, therefore, sent to juvenile detention centers rather than adult prisons.

Punishments can be imposed by educators, which include expulsion from school, suspension from the school, detention after school for additional study, or loss of certain school privileges or freedoms. Corporal punishment, while common in most cultures in the past, has become unacceptable in many modern societies. Parents may punish a child through different ways, including spankings, custodial sentences (such as chores), a "time-out" which restricts a child from doing what he or she wants to do, grounding, and removal of privileges or choices. In parenting, additional factors that increase the effectiveness of punishment include a verbal explanation of the reason for the punishment and a good relationship between the parent and the child.[7]

Reasons

There are many possible reasons that might be given to justify or explain why someone ought to be punished; here follows a broad outline of typical, possibly contradictory justifications.

Deterrence

Deterrence means dissuading someone from future wrongdoing, by making the punishment severe enough that the benefit gained from the offense is outweighed by the cost (and probability) of the punishment.

Deterrence is a common reason given for why someone should be punished. It is believed that punishment, especially when made known to—or witnessed by—the punished person's peers, can deter them from committing similar offenses, and thus serves a greater preventative good. However, it may be argued that using punishment as a deterrent has the fundamental flaw that human nature tends to ignore the possibility of punishment until they are caught, and actually can be attracted even more to the 'forbidden fruit', or even for various reasons glorify the punished, such as admiring a fellow for 'taking it like a man'. Furthermore, especially with children, feelings of bitterness and resentment can be aroused towards the punisher (parent) who threaten a child with punishment.

Punishment may also be used as part of the treatment for individuals with certain mental or developmental disorders, such as autism, to deter or at least reduce the occurrence of behaviors that can be injurious (such as head banging or self-mutilation), dangerous (such as biting others), or socially stigmatizing (such as stereotypical repetition of phrases or noises). In this case, each time the undesired behavior occurs, punishment is applied to reduce future instances. Generally the use of punishment in these situations is considered ethically acceptable if the corrected behavior is a significant threat to the individual and/or to others.

Education

Punishment demonstrates to the population which social norms are acceptable and which is not. People learn, through watching, reading about, and listening to different situations where people have broken the law and received a punishment, what they are able to do in society. Punishment teaches people what rights they have in their society and what behaviors are acceptable, and which actions will bring them punishment. This kind of education is important for socialization, as it helps people become functional members of the society in which they reside.

Honoring values

Punishment can be seen to honor the values codified in law. In this view, the value of human life is seen to be honored by the punishment of a murderer. Proponents of capital punishment have been known to base their position on this concept. Retributive justice is, in this view, a moral mandate that societies must guarantee and act upon. If wrongdoing goes unpunished, individual citizens may become demoralized, ultimately undermining the moral fabric of the society.

Incapacitation

Imprisonment has the effect of confining prisoners, physically preventing them from committing crimes against those outside, thus protecting the community. The most dangerous criminals may be sentenced to life imprisonment, or even to irreparable alternatives — the death penalty, or castration of sexual offenders — for this reason of the common good.

Rehabilitation

Punishment may be designed to reform and rehabilitate the wrongdoer so that they will not commit the offense again. This is distinguished from deterrence, in that the goal here is to change the offender's attitude to what they have done, and make them come to accept that their behavior was wrong.

Restoration

For minor offenses, punishment may take the form of the offender "righting the wrong." For example, a vandal might be made to clean up the mess he made. In more serious cases, punishment in the form of fines and compensation payments may also be considered a sort of "restoration." Some libertarians argue that full restoration or restitution on an individualistic basis is all that is ever just, and that this is compatible with both retributive justice and a utilitarian degree of deterrence.[8]

Revenge and retribution

Retribution is the practice of "getting even" with a wrongdoer — the suffering of the wrongdoer is seen as good in itself, even if it has no other benefits. One reason for societies to include this judicial element is to diminish the perceived need for street justice, blood revenge and vigilantism. However, some argue that this does not remove such acts of street justice and blood revenge from society, but that the responsibility for carrying them out is merely transferred to the state.

Retribution sets an important standard on punishment — the transgressor must get what he deserves, but no more. Therefore, a thief put to death is not retribution; a murderer put to death is. An important reason for punishment is not only deterrence, but also satisfying the unresolved resentment of victims and their families. One great difficulty of this approach is that of judging exactly what it is that the transgressor "deserves." For instance, it may be retribution to put a thief to death if he steals a family's only means of livelihood; conversely, mitigating circumstances may lead to the conclusion that the execution of a murderer is not retribution.

A specific way to elaborate this concept in the very punishment is the mirror punishment (the more literal applications of "an eye for an eye"), a penal form of 'poetic justice' which reflects the nature or means of the crime in the means of (mainly corporal) punishment.[9]

Religious views on punishment

Punishment may be applied on moral, especially religious, grounds as in penance (which is voluntary) or imposed in a theocracy with a religious police (as in a strict Islamic state like Iran or under the Taliban). In a theistic tradition, a government issuing punishments is working with God to uphold religious law. Punishment is also meant to allow the criminal to forgive himself/herself. When people are able to forgive themselves for a crime, God can forgive them as well. In religions that include karma in justice, such as those in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, punishment is seen as a balance to the evil committed, and to define good and evil for the people to follow. When evil is punished, it inspires people to be good, and reduces the amount of evil karma for future generations.[10]

Many religions have teachings and philosophies dealing with punishment. In Confucianism it is stated that "Heaven, in its wish to regulate the people, allows us for a day to make use of punishments" (Book of History 5.27.4, Marquis of Lu on Punishments). Hinduism regards punishment as an essential part of government of the people: "Punishment alone governs all created beings, punishment alone protects them, punishment watches over them while they sleep; the wise declare punishment to be the law. If punishment is properly inflicted after due consideration, it makes all people happy; but inflicted without consideration, it destroys everything" (Laws of Manu 7.18-20) and "A thief shall, running, approach the king, with flying hair, confessing that theft, saying, 'Thus I have done, punish me.' Whether he is punished or pardoned [after confessing], the thief is freed from the guilt of theft; but the king, if he punishes not, takes upon himself the guilt of the thief" (Laws of Manu 8.314, 316).

The guidelines for the Abrahamic religions come mainly from the Ten Commandments and the detailed descriptions in the Old Testament of penalties to be exacted for those violating rules. It is also noted that "He who renders true judgments is a co-worker with God" (Exodus 18.13).

However, Judaism handles punishment and misdeeds differently from other religions. If a wrongdoer commits a misdeed and apologizes to the person he or she offended, that person is required to forgive him or her. Similarly, God may forgive following apology for wrongdoing. Thus, Yom Kippur is the Jewish Day of Atonement, on which those of the Jewish faith abstain from eating or drinking to ask for God's forgiveness for their transgressions of the previous year.

Christianity warns that people face punishment in the afterlife if they do not live in the way that Jesus, who sacrificed his life in payment for our sins, taught is the proper way of life. Earthly punishment, however, is still considered necessary to maintain order within society and to rehabilitate those who stray. The repentant criminal, by willingly accepting his punishment, is forgiven by God and inherits future blessings.

Islam takes a similar view, in that performing misdeeds will result in punishment in the afterlife. It is noted, however, that "Every person who is tempted to go astray does not deserve punishment" (Nahjul Balagha, Saying 14).

Future of Punishment

In the past, punishment was an action solely between the offender and the victim, but now a host of laws protecting both the victim and offender are involved. The justice system, including a judge, jury, lawyers, medical staff, professional experts called to testify, and witnesses all play a role in the imposition of punishments.

With increasing prison reform, concern for the rights of prisoners, and the shift from physical force against offenders, punishment has changed and continues to change. Punishments once deemed humane are no longer acceptable, and advances in psychiatry have led to many criminal offenders being termed as mentally ill, and therefore not in control of their actions. This raise the issue of responsible some criminals are for their own actions and whether they are fit to be punished.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Adam Bedau, 2005. "Punishment" Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ "punish" Online Etymology Dictionary Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ Emile Durkheim (1895) On the Normality of Crime.

- ↑ Otto Kircheimer, and George Rusche. 2003. Punishment and Social Structure. (Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0765809216)

- ↑ Markus Dubber, The Right to be Punished: Autonomy and Its Demise in Modern Penal Thought. Law and History Review. (University of Illinois, 1998).

- ↑ David Garland. Punishment and Modern Society. (University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0226283821)

- ↑ W. Huitt, and J. Hummel. 1997. An Introduction to Operant (Instrumental) Conditioning. Valdosta State University Press. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ C. J. Lester, 2005. A Plague on Both Your Statist Houses: Why Libertarian Restitution Beats State Retribution and State Leniency Libertarian Alliance 2005. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ H. J. McCloskey. 1962. The Complexity of the Concepts of Punishment Philosophy. University of Melbourne.

- ↑ World Scriptures. www.euro-tongil.org.

- ↑ Issac Ehrlich, 1996. Crime, Punishment, and the Market for Offenses Journal of Economic Perspectives.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Garland, David. 1993. Punishment and Modern Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226283821.

- Gottschalk, Marie. 2006. The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521682916.

- Kircheimer, Otto, and George Rusche. 2003. Punishment and Social Structure. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0765809216.

- Lyons, Lewis. 2003. The History of Punishment. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1592280285.

- Western, Bruce. 2006. Punishment and Inequality in America. Russel Sage Foundation Publications. ISBN 978-0871548948.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved December 2, 2022.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.