Dormouse

| Dormice

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

African dormouse, Graphiurus sp.

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Graphiurinae

Leithiinae

Glirinae

|

Dormouse is the common name for any rodent of the family Gliridae (also known as Myoxidae or Muscardinidae), characterized by a generally squirrel- or chipmunk-like appearance, large eyes, short and curved claws, and in most species a bushy and long tail. Some species have thin and naked tails, such as the mouse-tailed dormice (genus Myomimus). Most dormice are adapted to a predominantly arboreal existence, although the mouse-tailed dormice dwell on the ground. Dormice particularly are known for their long periods of hibernation, with the etymology of the common name itself tracing from the word to sleep.

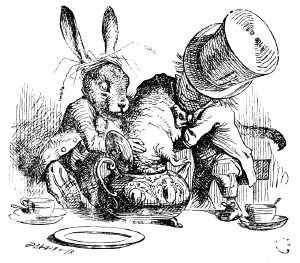

The almost 30 extant species are commonly placed into nine (or eight) genera. Because only one species of dormouse is native to the British Isles, the hazel dormouse or common dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius), in everyday English usage the term dormouse usually refers to this specific species. (The edible dormouse, Glis glis, has been accidentally introduced to the British Isles). The hazel dormouse gained fame as a character in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, where the Dormouse is often found falling asleep during the scene.

Dormice historically and currently have been used by humans as food, with records of such usage dating back thousands of years. In Ancient Rome, the edible dormouse was considered a delicacy, often used as either as a savory appetizer or as a dessert (dipped in honey and poppy seeds), with the Romans using a special kind of enclosure, a glirarium to rear the dormice for the table. Ranging in length from about 5 to 7.5 inches without the tail, the edible dormouse has stores of fat reserves that make them desirable as food and dormouse fat also was used by the Elizabethans to induce sleep.

Ecologically, this species also plays a valued role in food chains, with species having a diet that ranges from largely vegetarian to predominantly carnivorous, and being consumed by such predators as owls, snakes, weasels, and hawks. However, various pressures, including habitat destruction, have result in half of the species being at conservation risk.

Physical description

Many dormice have a squirrel-like or chipmunk-like appearance, including a bushy and long tail. (Both dormice and squirrles are rodents in the Sciurognathi suborder, but are members of different families.) However, a number of dormice have more of a resemblance to a mouse or rat, including thinner, more naked tails. Among those with more mouse-like tails are members of the genera Myomimus (known as mouse-tailed dormice, such as Roach's mouse-tailed dormouse, M. roachi) and such species as the desert dormouse, Selevinia betpakdalaensis, the sole member of its genera. While long, the tail is not prehensile. The fur of dormice is typically thick and soft (Niemann 2004).

Dormice range in size from about 2.5-3.1 inches (6.5-8 centimeters) in the Japanese dormouse (Glirulus japonicus) to 5.1-7.5 inches 913-19 centimeters) in the edible dormouse, Myoxus glis (or Glis glis) (Niemann 2004).

The feet of dormice have four toes on the front feet and five toes on the hind feet. The feet are adapted for an arboreal life style, with strong, curved claws on each toe and cushioned pads on the soles that assist in gripping. Furthermore, the hind feet are like the feet of squirrels in that they can be turned backwards, allowing the mammal to descent trees easily and hang head-first on a branch to feed (Niemann 2004).

Their dental formula is similar to that of squirrels, although they often lack premolars:

| 1.0.0-1.3 |

| 1.0.0-1.3 |

Dormice are unique among rodent families in that they lack a cecum.

Distribution and habitat

Dormice are found in Europe, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, western and central Asia, and Japan.

Dormice species most commonly dwell in forest, woodland, and scrub habitats, and are trypically arboreal, with some in dense forests only periodically leaving the canopy of tall trees. The garden or orchard dormouse (Eliomys querimus) and the edible dormice (Glis glis) sometimes are found in orchards, with the later even able to live on the ground. Only the mouse-tailed dormice (genus Myomimus) is known to exclusively live on the ground. The desert dormice (genus Selevinia) live in desert scrub. The African dormice (genus Graphiurus), which are all found in sub-Saharan Africa, typically are found in forested habiats. The Roach's mouse-tailed dormouse (Myomimus roachi) is found in various open habiats in southeastern Europe, not in forests (Niemann 2004).

Behavior, reproduction, life cycle, feeding

Most species of dormice are nocturnal. Other than during the mating season, they exhibit little territoriality and most species coexist in small family groups, with home ranges that vary widely between species and depend on the availability of food (Baudoin 1984).

Dormice have an excellent sense of hearing, and signal each other with a variety of vocalisations (Baudoin 1984). They are able to shed their tail to help evade a predator.

Dormice breed once or maybe twice a year, producing litters with an average of four young after a gestation period of 21-32 days. They can live for as long as five years in the wild. The young are born hairless and helpless, and their eyes do not open until about 18 days after birth. They typically become sexually mature after the end of their first hibernation.

Dormice tend to be omnivorous, typically feeding on fruits, berries, flowers, nuts and insects. The lack of a cecum, a part of the gut used in other species to ferment vegetable matter, means that low grade vegetable matter is only a minimal part of their diet (Niemann 2004). Some species are predeominately carnivorous (African, eidble, and hazel dormice), whilse some have a largely vegetarian diet (edible and hazel dormice); the desert dormouse may be unique that it is thought to be purely carnivorous (Niemann 2004).

Hibernation

One of the most notable characteristics of those dormice that live in temperate zones is hibernation. They can hibernate six months out of the year, or even longer if the weather remains sufficiently cool, sometimes waking for brief periods to eat food they had previously stored nearby. During the summer, they accumulate fat in their bodies, to nourish them through the hibernation period (Baudoin 1984). Even largely carnivorous dormice increase fat intake by seeking ntus and seeds before hiberation (Niemann 2004).

The name dormouse is based on this trait of hibernation; it comes from Anglo-Norman dormeus, which means "sleepy (one)"; the word was later altered by folk etymology to resemble the word "mouse." The sleepy behaviour of the dormouse character in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland also attests to this trait.

Evolution

Gliridae are one of the oldest extant rodent families, with a fossil record dating back to the early Eocene. As currently understood, they descended in Europe from early Paleogene ischyromyids such as Microparamys (Sparnacomys) chandoni. The early and middle Eocene genus Eogliravus represents the earliest and most primitive glirid taxon; the oldest species, Eogliravus wildi, is known from isolated teeth from the early Eocene of France and a complete specimen of the early middle Eocene of the Messel pit in Germany (Storch and Seiffert 2007). They appear in Africa in the upper Miocene and only relatively recently in Asia. Many types of extinct dormouse species have been identified. During the Pleistocene, giant dormice the size of large rats, such as Leithia melitensis, lived on the islands of Malta and Sicily (Savage and Long 1986).

Classification

The family consists of 29 living species, in three subfamilies and (arguably) 9 genera, although some (notably Selevinia betpakdalaensis) have been subject of taxonomic debate:

FAMILY GLIRIDAE - Dormice

- Subfamily Graphiurinae

- Genus Graphiurus, African dormice

- Angolan African dormouse, Graphiurus angolensis

- Christy's dormouse, Graphiurus christyi

- Jentink's dormouse, Graphiurus crassicaudatus

- Jouhnston's African dormouse, Graphiurus johnstoni

- Kellen's dormouse, Graphiurus kelleni

- Lorrain dormouse, Graphiurus lorraineus

- Small-eared dormouse, Graphiurus microtis

- Monard's dormouse, Graphiurus monardi

- Woodland dormouse, Graphiurus murinus

- Nagtglas's African dormouse, Graphiurus nagtglasii

- Spectacled dormouse, Graphiurus ocularis

- Rock dormouse, Graphiurus platyops

- Stone dormouse, Graphiurus rupicola

- Silent dormouse, Graphiurus surdus

- Graphiurus walterverheyeni (Holden and Levine 2009)

- Genus Graphiurus, African dormice

- Subfamily Leithiinae

- Genus Chaetocauda

- Chinese dormouse, Chaetocauda sichuanensis

- Genus Dryomys

- Woolly dormouse, Dryomys laniger

- Balochistan Forest dormouse, Dryomys niethammeri

- Forest dormouse, Dryomys nitedula

- Genus Eliomys, garden dormice

- Asian garden dormouse, Eliomys melanurus

- Maghreb garden dormouse, Eliomys munbyanus

- Garden dormouse, Eliomys quercinus

- Genus Hypnomys† (Balearic dormouse)

- Majorcan giant dormouse, Hypnomys morphaeus†

- Minorcan giant dormouse, Hypnomys mahonensis†

- Genus Muscardinus

- Hazel dormouse, Muscardinus avellanarius

- Genus Myomimus, mouse-tailed dormice

- Masked mouse-tailed dormouse, Myomimus personatus

- Roach's mouse-tailed dormouse, Myomimus roachi

- Setzer's mouse-tailed dormouse, Myomimus setzeri

- Genus Selevinia

- Desert dormouse, Selevinia betpakdalaensis

- Genus Chaetocauda

- Subfamily Glirinae

- Genus Glirulus

- Japanese dormouse, Glirulus japonicus

- Genus Glis

- Edible dormouse, Glis glis

- Genus Glirulus

Fossil species

- Subfamily Bransatoglirinae

- Genus Oligodyromys

- Genus Bransatoglis

- Bransatoglis adroveri Majorca, Early Oligocene

- Bransatoglis planus Eurasia, Early Oligocene

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baudoin, C. 1984. Dormouse. Pages 210-212 in D. Macdonald (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0871968711.

- Holden, M. E. 2005. Family Gliridae. Pages 819-841 in D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal Species of the World a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. ISBN 0801882214.

- Holden, M. E., and R. S. Levine. 2009. [http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1206/582-9.1 Systematic revision of Sub-Saharan African dormice (Rodentia: Gliridae: Graphiurus) Part II: Description of a new species of Graphiurus from the Central Congo Basin, including morphological and ecological niche comparisons with G. crassicaudatus and G. lorraineus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 331: 314-355.

- Niemann, D. W. 2004. Dormice (Myoxidae). Pages 317 to 318 in B. Grzimek et al., Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., vol. 16. Detroit, MI: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787657921.

- Savage, R. J. G., and M. R. Long. 1986. Mammal Evolution: An Illustrated Guide. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 081601194X.

- Storch, G., and C. Seiffert. 2007. Extraordinarily preserved specimen of the oldest known glirid from the middle Eocene of Messel (Rodentia). Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 27(1): 189–194.

|

Sciuromorpha: †Allomyidae | Aplodontiidae | †Mylagaulidae | †Reithroparamyidae | Sciuridae | Gliridae |

|

Castorimorpha: †Eutypomyidae | Castoridae | †Rhizospalacidae | †Eomyidae | †Heliscomyidae | †Mojavemyidae | Heteromyidae | Geomyidae |

|

Myomorpha: †Armintomidae | Dipodidae | Zapodidae | †Anomalomyidae | †Simimyidae | Platacanthomyidae | Spalacidae | Calomyscidae | Nesomyidae | Cricetidae | Muridae |

|

Anomaluromorpha: Anomaluridae | †Parapedetidae | Pedetidae |

|

Hystricomorpha: †Tamquammyidae | Ctenodactylidae | Diatomyidae | †Yuomyidae | †Chapattimyidae | †Tsaganomyidae | †"Baluchimyinae" | †Bathyergoididae | Bathyergidae | Hystricidae | †Myophiomyidae | †Diamantomyidae | †Phiomyidae | †Kenyamyidae | Petromuridae | Thryonomyidae | Erethizontidae | Chinchillidae | Dinomyidae | Caviidae | Dasyproctidae | †Eocardiidae | Cuniculidae | Ctenomyidae | Octodontidae | †Neoepiblemidae | Abrocomidae | Echimyidae | Myocastoridae | Capromyidae | †Heptaxodontidae |

|

Prehistoric rodents (incertae sedis): †Eurymylidae | †Cocomyidae | †Alagomyidae | †Ivanantoniidae | †Laredomyidae | †Ischyromyidae | †Theridomyidae | †Protoptychidae | †Zegdoumyidae | †Sciuravidae | †Cylindrodontidae |

|

† indicates extinct taxa |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.