| Ted Kennedy | |

| |

United States Senator

| |

| In office November 7, 1962 – August 25, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin A. Smith II |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Paul G. Kirk |

Chair of the Senate Health Committee

| |

| In office January 3, 2007 – August 25, 2009 On leave: June 9 – August 25, 2009* | |

| Preceded by | Mike Enzi |

| Succeeded by | Chris Dodd (acting) |

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Jeffords |

| Succeeded by | Judd Gregg |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 20, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Jeffords |

| Succeeded by | Jim Jeffords |

| In office January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Orrin Hatch |

| Succeeded by | Nancy Kassebaum |

Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee

| |

| In office January 3, 1979 – January 3, 1981 | |

| Preceded by | James Eastland |

| Succeeded by | Strom Thurmond |

Senate Majority Whip

| |

| In office January 3, 1969 – January 3, 1971 | |

| Preceded by | Russell B. Long |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| Born | February 22 1932 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | August 25 2009 (aged 77) Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Joan Bennett (m. 1958; div. 1983) Vicki Reggie (m. 1992) |

| Relations | Kennedy family |

| Children | Kara ·Edward Jr. ·Patrick |

| Signature |

|

| Website | Official website |

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party and the Kennedy political family, he was the second most senior member of the Senate when he died and the third-longest-continuously-serving senator in United States history. Kennedy was a brother of President John F. Kennedy and U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy—both victims of assassination—and was the father of Congressman Patrick J. Kennedy.

Kennedy was 30 years old when he first entered the Senate following a November 1962 special election in Massachusetts to fill the vacant seat previously held by his brother John, who had taken office as the president. He was elected to a full six-year term in 1964 and was later re-elected seven more times. The Chappaquiddick incident in 1969 resulted in the death of his automobile passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, a former campaign worker for his brother Robert's Presidential campaign. He pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident and later received a two-month suspended sentence. The incident and its aftermath hindered his chances of ever becoming president. His only attempt, in the 1980 election, resulted in a Democratic primary campaign loss to the incumbent president, Jimmy Carter.

Kennedy was known for his oratorical skills. His 1968 eulogy for his brother Robert and his 1980 rallying cry for modern American liberalism were among his best-known speeches. He became recognized as "The Lion of the Senate" through his long tenure and influence. Kennedy and his staff wrote more than 300 bills that were enacted into law. Unabashedly liberal, Kennedy championed an interventionist government that emphasized economic and social justice, but he was also known for working with Republicans to find compromises. Kennedy played a major role in passing many laws, including the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the National Cancer Act of 1971, the COBRA health insurance provision, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Ryan White AIDS Care Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Mental Health Parity Act, the S-CHIP children's health program, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act. During the 2000s, he led several unsuccessful immigration reform efforts. Over the course of his Senate career, Kennedy made efforts to enact universal health care, which he called the "cause of my life." Despite his role as a major figure and spokesman for American progressivism, Kennedy was a champion of the Senate and Senate collegiality who worked across the aisle with conservative Senators like Orrin Hatch on issues of mutual interest.

Kennedy died on August 25, 2009 of a malignant brain tumor at his home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, and was buried near his brothers John and Robert at Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life

Edward Moore Kennedy was born on February 22, 1932, at St. Margaret's Hospital in the Dorchester section of Boston, Massachusetts. He was the last of the nine children of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, members of prominent Irish American families in Boston,[1] who constituted one of the wealthiest families in the nation once they were joined.[2] His eight siblings were Joseph Jr., John, Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia, Robert, and Jean. John asked to be the newborn's godfather, a request his parents honored, though they did not agree to his request to name the baby George Washington Kennedy (Ted was born on President George Washington's 200th birthday) and instead named him after their father's assistant.[3]

As a child, Ted was frequently uprooted by his family's moves among Bronxville, New York; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts; Palm Beach, Florida; and the Court of St. James's, in London, England.[4] His formal education started at Gibbs School in Kensington, London.[5] He had attended ten schools by the age of eleven; this was a series of disruptions that interfered with his academic success.[6] He was an altar boy at the St. Joseph's Church and was seven when he received his First Communion from Pope Pius XII in the Vatican.[7] He spent sixth and seventh grades at the Fessenden School, where he was a mediocre student, and eighth grade at Cranwell Preparatory School; both schools located in Massachusetts.[4] He was the youngest child and his parents were affectionate towards him, but they also compared him unfavorably with his older brothers. Ted's affable maternal grandfather, John F. Fitzgerald, was the Mayor of Boston, a U.S. Congressman, and an early political and personal influence.[1]

Between the ages of eight and sixteen, Ted suffered the traumas of Rosemary's failed lobotomy and the deaths of Joseph Jr. in World War II and Kathleen in an airplane crash.[1] He spent his four high-school years at Milton Academy, a preparatory school in Milton, Massachusetts, where he received B and C grades and, in 1950, finished 36th in a graduating class of 56. He did well at football there, playing on the varsity in his last two years; the school's headmaster later described his play as "absolutely fearless ... he would have tackled an express train to New York if you asked ... he loved contact sports."[8] Kennedy also played on the tennis team and was in the drama, debate, and glee clubs.

College, military service, and law school

Like his father and brothers before him, Ted graduated from Harvard College. An offense and defensive end on the football team, Kennedy was anxious about maintaining his eligibility for athletics for the next year,[1] so at the end of his second semester in May 1951 he had a classmate take his place at a Spanish exam. The deception was immediately discovered and both students were expelled for cheating. In a standard Harvard treatment for serious disciplinary cases, they were told they could apply for readmission within a year or two if they demonstrated good behavior during that time.[9][10]

In June 1951, Kennedy enlisted in the United States Army and signed up for an optional four-year term that was shortened to the minimum of two years after his father intervened. Following basic training at Fort Dix in New Jersey, he requested assignment to Fort Holabird in Maryland for Army Intelligence training, but was dropped without explanation after a few weeks. He went to Camp Gordon in Georgia for training in the Military Police Corps. In June 1952, Kennedy was assigned to the honor guard at SHAPE headquarters in Paris, France.[9] His father's political connections ensured that he was not deployed to the ongoing Korean War.[11] After 21 months, he was discharged in March 1953 as a private first class.[9]

Kennedy re-entered Harvard in the summer of 1953 and improved his study habits.[1] His brother John was a U.S. Senator and the family was attracting more public attention.[12] Academically, Kennedy received mediocre grades for his first three years, improved to a B average for his senior year, and finished barely in the top half of his class. Kennedy graduated from Harvard at age 24 in 1956 with an AB in history and government.[13]

Due to his low grades, Kennedy was not accepted by Harvard Law School.[10] He instead followed his brother Bobby and enrolled in the University of Virginia School of Law in 1956.[1] That acceptance was controversial among faculty and alumni, who judged Kennedy's past cheating episodes at Harvard to be incompatible with the University of Virginia's honor code; it took a full faculty vote to admit him.[14] Kennedy also attended the Hague Academy of International Law during one summer.[15] At Virginia, Kennedy felt that he had to study "four times as hard and four times as long" as other students to keep up with them.[16] He received mostly C grades and was in the middle of the class ranking, but was the winner of the prestigious William Minor Lile Moot Court Competition.[1] He was elected head of the Student Legal Forum and brought many prominent speakers to the campus via his family connections.[17] While there, his careless driving caught up with him and he was charged with reckless driving and driving without a license.[1] While attending law school, he was officially named as manager of his brother John's 1958 Senate re-election campaign; Ted's ability to connect with ordinary voters on the street helped bring a record-setting victory margin that gave credibility to John's presidential aspirations.[18] Ted graduated from law school in 1959.[17]

In October 1957 (early in his second year of law school), Kennedy met Joan Bennett at Manhattanville College; they were introduced after a dedication speech for a gymnasium that his family had donated at the campus. Bennett was a senior at Manhattanville and had worked as a model and won beauty contests, but she was unfamiliar with the world of politics. After the couple became engaged, she grew nervous about marrying someone she did not know that well, but Joe Kennedy insisted that the wedding should proceed.[19] The couple was married by Cardinal Francis Spellman on November 29, 1958, at St. Joseph's Church in Bronxville, New York,[1] with a reception at nearby Siwanoy Country Club.[20] Ted and Joan had three children: Kara (1960–2011), Ted Jr. (b. 1961) and Patrick (b. 1967). By the 1970s, the marriage became troubled due to Ted's infidelity and Joan's growing alcoholism. They would separate in 1977 and eventually divorce in 1983.

Early career

Kennedy was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1959. In 1960, his brother John announced his candidacy for President of the United States and Ted managed his campaign in the Western states.[1] The seven weeks he spent in Wisconsin helped his brother win the first contested primary of the season there and a similar time spent in Wyoming was rewarded when a unanimous vote from that state's delegates put his brother over the top at the 1960 Democratic National Convention.[21]

Following his victory in the presidential election, John resigned from his seat as U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, but Ted was not eligible to fill the vacancy until his thirtieth birthday on February 22, 1962.[22] Ted's brothers were not in favor of his running immediately, but Ted ultimately coveted the Senate seat as an accomplishment to match his brothers, and their father overruled them. John asked Massachusetts Governor Foster Furcolo to name Kennedy family friend Ben Smith as interim senator for John's unexpired term, which he did in December 1960.[23] This kept the seat available for Ted.

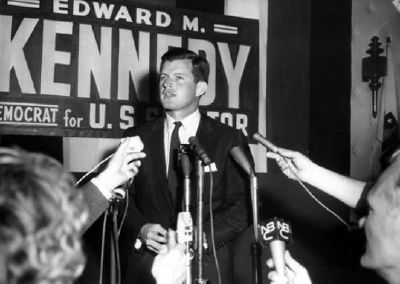

In the November special election, Kennedy defeated Republican George Cabot Lodge II, product of another noted Massachusetts political family, gaining 55 percent of the vote.

Brothers' assassinations

Kennedy was sworn into the Senate on November 7, 1962. He maintained a deferential attitude towards the older Southern members when he first entered the Senate. He recognized the seniority system in the Senate, avoiding publicity and focusing on committee work and local issues.[24] Compared to his brothers in office, he lacked John's sophistication and Robert's intense, sometimes grating drive, but was more affable than either of them.

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was presiding over the Senate—a task given to junior members—when an aide rushed in to tell him that his brother, President John F. Kennedy, had been shot. His brother Robert soon told him that the President was dead. Ted and his sister Eunice Kennedy Shriver immediately flew to the family home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, to give the news to their invalid father, who had been afflicted by a stroke suffered two years earlier.

Kennedy initially said he had "no reservations" about the expanding U.S. role in the Vietnam War and acknowledged that it would be a "long and enduring struggle." He held hearings on the plight of refugees in the conflict, which revealed that the U.S. government had no coherent policy for refugees.[25] Kennedy also tried to reform "unfair" and "inequitable" aspects of the draft. By the time of a January 1968 trip to Vietnam, Kennedy was disillusioned by the lack of U.S. progress, and suggested publicly that the U.S. should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out."[26] On March 31, 1968 President Lyndon Johnson made a surprise announcement that he would not seek the Presidency again in the 1968 election.

Ted initially advised his brother Robert against challenging for the Democratic nomination in the 1968 presidential election. Once Eugene McCarthy's strong showing in the New Hampshire primary led to Robert's presidential campaign starting in March 1968, Ted recruited political leaders for endorsements to his brother in the western states.[27] Ted was in San Francisco when his brother Robert won the crucial California primary on June 4, 1968, and then after midnight, Robert was shot in Los Angeles and died a day later. Ted Kennedy was devastated by his brother's death, as he was closest to Robert among those in the Kennedy family. Kennedy aide Frank Mankiewicz said of seeing Ted at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief." At Robert's funeral, Kennedy eulogized his older brother:

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it. Those of us who loved him and who take him to his rest today, pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will some day come to pass for all the world. As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."[28]

After the deaths of his brothers, Kennedy took on the role of a surrogate father for his 13 nephews and nieces.[29] By some reports, he also negotiated the October 1968 marital contract between Jacqueline Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis.[30]

Chappaquiddick incident

Following Republican Richard Nixon's victory in November, Kennedy was widely assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination.[31] In January 1969, Kennedy defeated Louisiana Senator Russell B. Long by a 31–26 margin to become Senate Majority Whip, the youngest person to attain that position.[32] While this further boosted his presidential image, he also appeared conflicted by the inevitability of having to run for the position;[29] "Few who knew him doubted that in one sense he very much wanted to take that path", Time magazine reported, but "he had a fatalistic, almost doomed feeling about the prospect".

On the night of July 18, 1969, Kennedy was at Chappaquiddick Island on the eastern end of Martha's Vineyard. He was hosting a party for the Boiler Room Girls, a group of young women who had worked on his brother Robert's ill-fated 1968 presidential campaign.[31] Kennedy left the party with one of the women, 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne.

Driving a 1967 Oldsmobile Delmont 88, he attempted to cross the Dike Bridge, which did not have a guardrail at that time. Kennedy later denied that he was drunk but he lost control of his vehicle and crashed in the Poucha Pond inlet, which was a tidal channel on Chappaquiddick Island. Kennedy escaped from the overturned vehicle, and, by his description, dove below the surface seven or eight times, vainly attempting to reach and rescue Kopechne. Ultimately, he swam to shore and left the scene, with Kopechne still trapped inside the vehicle. Kennedy did not report the accident to authorities until the next morning, by which time Kopechne's body had already been discovered.[31] Kennedy's cousin Joe Gargan later said that he and Kennedy's friend Paul Markham, both of whom were at the party and came to the scene, urged Kennedy to report it at the time.[33]

A week after the incident, Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and was given a suspended sentence of two months in jail. That night, he gave a national broadcast in which he said, "I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately," but he denied driving under the influence of alcohol and also denied any immoral conduct between him and Kopechne.[31] Kennedy asked the Massachusetts electorate whether he should stay in office or resign; after getting a favorable response in messages sent to him, Kennedy announced on July 30 that he would remain in the Senate and run for re-election the next year.[34]

In January 1970, an inquest into Kopechne's death was held in Edgartown, Massachusetts. At the request of Kennedy's lawyers, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ordered the inquest to be conducted in secret.[35] The presiding judge, James A. Boyle, concluded that some aspects of Kennedy's story about that night were not true, and that negligent driving "appears to have contributed" to the death of Kopechne. A grand jury on Martha's Vineyard conducted a two-day investigation in April 1970 but issued no indictment, after which Boyle made his inquest report public. Kennedy deemed its conclusions "not justified."[31] Questions about the Chappaquiddick incident generated a large number of articles and books during the following years.

1980 presidential campaign

The Chappaquiddick incident impacted any Presidential aspirations Kennedy might have had in 1972 and 1976. In 1980, he would have to face an incumbent President from his own party. As the Democratic nominee, Jimmy Carter developed little relationship with Kennedy during his primary campaign, the convention, or the general election campaign.[36] This continued during the Carter administration, which were difficult year for Kennedy. He had been the most important Democrat in Washington ever since his brother Robert's death, but now Carter was, and Kennedy at first did not have a full committee chairmanship with which to wield influence.[37] Carter in turn sometimes resented Kennedy's status as a political celebrity.[3] Despite generally similar ideologies, their priorities were different. Kennedy expressed to reporters that he was content with his congressional role and viewed presidential ambitions as almost far-fetched, but Kennedy finally decided to seek the Democratic nomination in the 1980 presidential election by launching an unusual, insurgent campaign against the incumbent Carter.[38]

A midsummer 1978 poll showed that Democrats preferred Kennedy over Carter by a 5-to-3 margin. Labor unions urged Kennedy to run, as did some Democratic party officials who feared that Carter's unpopularity could result in heavy losses in the 1980 congressional elections.[39] Kennedy decided to run in August 1979, when polls showed him with a 2-to-1 advantage over Carter;[40] Carter's approval rating slipped to 19 percent.[41] Kennedy formally announced his campaign on November 7, 1979, at Boston's Faneuil Hall.[42] The Iranian hostage crisis, which began on November 4, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which began on December 27, prompted the electorate to rally around the president and allowed Carter to pursue a Rose Garden strategy of staying at the White House, which kept Kennedy's campaign out of the headlines.[42]

Kennedy's campaign staff was disorganized and Kennedy was initially an ineffective campaigner.[43] The Chappaquiddick incident emerged as a more significant issue than the staff had expected, with several newspaper columnists and editorials criticizing Kennedy's answers on the matter.[44] In the January 1980 Iowa caucuses that initiated the primaries season, Carter demolished Kennedy by a 59–31 percent margin. Kennedy lost three New England contests.[42] Kennedy did form a more coherent message about why he was running, saying at Georgetown University: "I believe we must not permit the dream of social progress to be shattered by those whose promises have failed."[45] However, concerns over Chappaquiddick and issues related to personal character prevented Kennedy from gaining the support of many people who were disillusioned with Carter.[46] During a St. Patrick's Day Parade in Chicago, Kennedy had to wear a bullet-proof vest due to assassination threats, and hecklers yelled "Where's Mary Jo?" at him.[47] In the key March 18 primary in Illinois, Kennedy failed to gain the support of Catholic voters, and Carter crushed him, winning 155 of 169 delegates.[48]

With little mathematical hope of winning the nomination and polls showing another likely defeat in the New York primary, Kennedy prepared to withdraw from the race. However, partially due to Jewish voter unhappiness with a U.S. vote at the United Nations against Israeli settlements in the West Bank, Kennedy staged an upset and won the March 25 vote by a 59–41 percent margin. Carter responded with an advertising campaign that attacked Kennedy's character in general without explicitly mentioning Chappaquiddick, but Kennedy still managed a narrow win in the April 22 Pennsylvania primary.[42] Carter won 11 of 12 primaries held in May, while on the June 3 Super Tuesday primaries, Kennedy won California, New Jersey, and three smaller states out of eight contests.[49] Overall, Kennedy had won 10 presidential primaries against Carter, who won 24.

Although Carter now had enough delegates to clinch the nomination, Kennedy carried his campaign on to the 1980 Democratic National Convention in August in New York, hoping to pass a rule there that would free delegates from being bound by primary results and open the convention. This move failed on the first night of the convention, and Kennedy withdrew.[42] On the second night, August 12, Kennedy delivered the most famous speech of his career. Drawing on allusions to and quotes of Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Alfred Lord Tennyson to say that American liberalism was not passé,[50] he concluded with the words:

For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.[51]

The Madison Square Garden audience reacted with wild applause and demonstrations for half an hour.[42] On the final night, Kennedy arrived late after Carter's acceptance speech and while he shook Carter's hand, he failed to raise Carter's arm in the traditional show of party unity.[48] Carter's difficulty in securing the assistance of Kennedy supporters during the election campaign has long been considered as a contributing factor to his November defeat by Ronald Reagan.

Senate Career

Health Care

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder, United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther.[52] In May 1970, Reuther died and Senator Ralph Yarborough, chairman of the full Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee and its Health subcommittee, lost his primary election, propelling Kennedy into a leadership role on the issue of national health insurance.[53] Kennedy introduced a bipartisan bill in August 1970 for single-payer universal national health insurance with no cost sharing, paid for by payroll taxes and general federal revenue. Health care would remain one of the issues that Kennedy would champion throughout his career.

In February 1971, President Nixon proposed health insurance reform—an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, federalization of Medicaid for the poor with dependent minor children, and support for health maintenance organizations. Hearings on national health insurance were held in 1971, but no bill had the support of House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committee chairmen Representative Wilbur Mills and Senator Russell Long.[54] Kennedy sponsored and helped pass the limited Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973.[55]

In February 1974, President Nixon proposed more comprehensive health insurance reform—an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, replacement of Medicaid by state-run health insurance plans available to all with income-based premiums and cost sharing, and replacement of Medicare with a new federal program that eliminated the limit on hospital days, added income-based out-of-pocket limits, and added outpatient prescription drug coverage.[56] In April 1974, Kennedy and Mills introduced a bill for near-universal national health insurance with benefits identical to the expanded Nixon plan, but with mandatory participation by employers and employees through payroll taxes. Both plans were criticized by labor, consumer, and senior citizen organizations because of their substantial cost sharing.[57] In August 1974, after Nixon's resignation and President Ford's call for health insurance reform, Mills tried to advance a compromise based on Nixon's plan but with mandatory participation by employers and employees through premiums to private health insurance companies. He gave up when he was unable to get more than a 13–12 majority of his committee to support his compromise plan.

After the 1976 election of President Carter, Kennedy renewed his efforts. As a candidate, Carter had proposed health care reform that included key features of Kennedy's national health insurance bill, but in December 1977, President Carter told Kennedy his bill must be changed to preserve a large role for private insurance companies, minimize federal spending (precluding payroll tax financing), and be phased-in so as to not interfere with Carter's paramount domestic policy objective—balancing the federal budget.[58] Kennedy and labor compromised, making the requested changes, but broke with Carter in July 1978 when he would not commit to pursuing a single bill with a fixed schedule for phasing-in comprehensive coverage.[58] Frustrated by Carter's budgetary concerns and political caution,[2] Kennedy said in a December 1978 speech on national health insurance at the Democratic midterm convention that "sometimes a party must sail against the wind" and in particular should provide health care as "a basic right for all, not just an expensive privilege for the few."[59]

In May 1979, Kennedy proposed a new bipartisan universal national health insurance bill. Provision included a choice of competing federally regulated private health insurance plans with no cost sharing-financed by income-based premiums via an employer mandate and individual mandate-replacement of Medicaid by government payment of premiums to private insurers, and enhancement of Medicare by adding prescription drug coverage and eliminating premiums and cost sharing.[60] In June 1979, Carter proposed more limited health insurance reform—an employer mandate to provide catastrophic private health insurance plus coverage without cost sharing for pregnant women and infants, federalization of Medicaid with extension to all of the very poor, plus enhancement of Medicare by adding catastrophic coverage. Neither plan gained any traction in Congress and the failure to come to agreement represented the final political breach between the two. Carter wrote in 1982 that Kennedy's disagreements with Carter's proposed approach "ironically" thwarted Carter's efforts to provide a comprehensive health-care system for the country.[61] In turn, Kennedy wrote in his memoir that his relationship with Carter was "unhealthy" and that "Clearly President Carter was a difficult man to convince – of anything."[62]

Much later, following the failure of the Clinton health care plan, Kennedy went against his previous strategy and sought incremental measures instead.[63] Kennedy worked with Republican Senator Nancy Kassebaum to create and pass the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in 1996, which set new marks for portability of insurance and confidentiality of records. The same year, Kennedy's Mental Health Parity Act forced insurance companies to treat mental health payments the same as others with respect to limits reached. In 1997, Kennedy was the prime mover behind the State Children's Health Insurance Program,[64] which used increased tobacco taxes to fund the largest expansion of taxpayer-funded health insurance coverage for children in the U.S. since Medicaid began in the 1960s.

Foreign Policy

In April 1974, Kennedy traveled to the Soviet Union, where he met with leader Leonid Brezhnev and advocated a full nuclear test ban as well as relaxed emigration, gave a speech at Moscow State University, met with Soviet dissidents, and secured an exit visa for famed cellist Mstislav Rostropovich.[65] Kennedy's Subcommittee on Refugees and Escapees continued to focus on Vietnam, especially after the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

Kennedy visited China on a goodwill mission in late December 1977, meeting with leader Deng Xiaoping and eventually gained permission for a number of Mainland Chinese nationals to leave the country; in 1978, he also visited the Soviet Union, meeting with Brezhnev and also with dissidents there again.[66] During the 1970s, Kennedy also showed interest in nuclear disarmament, and as part of his efforts in this field even visited Hiroshima in January 1978 and gave a public speech to that effect at Hiroshima University.[67] He became chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1978.

After the election of Ronald Reagan, Kennedy became very visible in opposing aspects of the foreign policy of the Reagan administration, including U.S. intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War and U.S. support for the Contras in Nicaragua, and in opposing Reagan-supported weapons systems, including the B-1 bomber, the MX missile, and the Strategic Defense Initiative. Kennedy became the Senate's leading advocate for a nuclear freeze and was a critic of Reagan's confrontational policies toward the Soviet Union.[68][69]

A 1983 KGB memo indicates that Kennedy engaged in back-channel communication with the Soviet Union. According to a May 14, 1983 memorandum from KGB chairman Viktor Chebrikov to general secretary Yuri Andropov, former U.S. Senator John Tunney—a friend and former college roommate of Kennedy's—visited Moscow that month and conveyed a message from Kennedy to Andropov.[70] The memo indicates that the stated purpose of the communication was to "'root out the threat of nuclear war', 'improve Soviet-American relations' and 'define the safety of the world'". Chebrikov wrote that Kennedy was "'very troubled by the current state of Soviet-American relations'" and believed that the "'only real threats to Reagan [were] problems of war and peace and Soviet-American relations'". Chebrikov added that those issues, "'according to the senator, will without a doubt become the most important of the [1984] election campaign'".[71] Kennedy reportedly offered to visit Moscow "'to arm Soviet officials with explanations regarding problems of nuclear disarmament so they may be better prepared and more convincing during appearances in the USA'" and to set up U.S. television appearances for Andropov.[70]

Chebrikov also noted "a little-hidden secret that [Kennedy] intended to run for president in 1988 and that the Democratic Party 'may officially turn to him to lead the fight against the Republicans' in 1984 — turning the proposal from one purely about international cooperation to one tinged with personal political aspiration."[71] Andropov was unimpressed by Kennedy's overtures.[72] After the Chebrikov memo was unearthed, both Tunney and a Kennedy spokesperson denied that it was true.[71]

Kennedy staged a high-profile trip to South Africa in January 1985.[73] He defied both the apartheid government's wishes and militant leftist AZAPO demonstrators by spending a night in the Soweto home of Bishop Desmond Tutu and also visited Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela.[42] Upon returning, Kennedy became a leader in the push for economic sanctions against South Africa; collaborating with Senator Lowell Weicker, he secured Senate passage, and the overriding of Reagan's veto, of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.[73] Despite their many political differences, Kennedy and Reagan had a good personal relationship,[74] and with the administration's approval Kennedy traveled to the Soviet Union in 1986 to act as a go-between in arms control negotiations with reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.[42] The discussions were productive, and Kennedy also helped gain the release of a number of Soviet Jewish refuseniks, including Anatoly Shcharansky.[75]

Supreme Court Confirmations

Robert Bork

One of Kennedy's biggest battles in the Senate came with Reagan's July 1987 nomination of Judge Robert Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court. Kennedy saw a possible Bork appointment as leading to a dismantling of civil rights law that he had helped put into place, and feared Bork's originalist judicial philosophy.[42] Kennedy's staff had researched Bork's writings and record, and within an hour of the nomination – which was initially expected to succeed – Kennedy went on the Senate floor to announce his opposition:

Robert Bork's America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens ...[76]

The incendiary rhetoric of what became known as the "Robert Bork's America" speech enraged Bork supporters, who considered it slanderous, and worried some Democrats as well.[76] Bork responded, "There was not a line in that speech that was accurate."[77] In 1988, an analysis published in the Western Political Quarterly of amicus curiae briefs filed by U.S. Solicitors General during the Warren and Burger Courts found that during Bork's tenure in the position during the Nixon and Ford Administrations (1973–1977), Bork took liberal positions in the aggregate as often as Thurgood Marshall did during the Johnson Administration (1965–1967) and more often than Wade H. McCree did during the Carter Administration (1977–1981), in part because Bork filed briefs in favor of the litigates in civil rights cases 75 percent of the time (contradicting a previous review of his civil rights record published in 1983).[78]

However, the Reagan administration was unprepared for the assault, and the speech froze some Democrats from supporting the nomination and gave Kennedy and other Bork opponents time to prepare the case against him.[79] When the September 1987 Judiciary Committee hearings began, Kennedy challenged Bork forcefully on civil rights, privacy, women's rights, and other issues. Bork's own demeanor hurt him,[76] and the nomination was defeated both in committee and the full Senate.[42] The tone of the Bork battle changed the way Washington worked – with controversial nominees or candidates now experiencing all-out war waged against them – and the ramifications of it were still being felt decades later.[79]

Clarence Thomas

Bork and Clarence Thomas were the two most contentious Supreme Court nominations in United States history.[80] When the Thomas hearings began in September 1991, Kennedy pressed Thomas on his unwillingness to express an opinion about Roe v. Wade, but the nomination appeared headed for success.[81] When Anita Hill brought the sexual harassment charges against Thomas the following month, the nomination battle dominated public discourse. Kennedy was hamstrung by his past reputation and the ongoing developments in the William Kennedy Smith rape case.[82] He said almost nothing until the third day of the Thomas–Hill hearings, and when he did it was criticized by Hill supporters for being too little, too late.

Biographer Adam Clymer rated Kennedy's silence during the Thomas hearings as the worst moment of his Senate career. Writer Anna Quindlen said "[Kennedy] let us down because he had to; he was muzzled by the facts of his life."[82] On the day before the full Senate vote, Kennedy gave an impassioned speech against Thomas, declaring that the treatment of Hill had been "shameful" and that "[t]o give the benefit of the doubt to Judge Thomas is to say that Judge Thomas is more important than the Supreme Court."[83] He then voted against the nomination. Thomas was confirmed by a 52–48 vote, one of the narrowest margins ever for a successful nomination.[82]

Lion of the Senate

Kennedy's role as a liberal lion in the Senate came to the fore in 1995, when the Republican Revolution took control and legislation intending to fulfill the Contract with America was coming from Newt Gingrich's House of Representatives. Many Democrats in the Senate and the country overall felt depressed but Kennedy rallied forces to combat the Republicans.[84] By the beginning of 1996, most of the Contract had failed to pass the Senate and the Democrats could once again move forward with legislation, almost all of it coming out of Kennedy's staff.[85]

In 1996, Kennedy secured an increase in the minimum wage, which was one of his favorite issues;[86] there would not be another increase for ten years.

After the long, disputed post-presidential election battle in Florida in 2000, many Democrats in Congress did not want to work with incoming President George W. Bush. Kennedy, however, saw Bush as genuinely interested in a major overhaul of elementary and secondary education, Bush saw Kennedy as a potential major ally in the Senate, and the two partnered together on the legislation.[87] Kennedy accepted provisions governing mandatory student testing and teacher accountability that other Democrats and the National Education Association did not like, in return for increased funding levels for education. The No Child Left Behind Act was passed by Congress in May and June 2001 and signed into law by Bush in January 2002. Kennedy soon became disenchanted with the implementation of the act, however, saying for 2003 that it was $9 billion short of the $29 billion authorized. Kennedy said, "The tragedy is that these long overdue reforms are finally in place, but the funds are not,"[87] and accused Bush of not living up to his personal word on the matter. Other Democrats concluded that Kennedy's penchant for cross-party deals had gotten the better of him. The White House defended its spending levels given the context of two wars going on. He would continue his cross-party deals in the coming years.

Despite the strained relationship between Kennedy and Bush over No Child Left Behind spending, the two attempted to work together again on extending Medicare to cover prescription drug benefits. Kennedy's strategy was again doubted by other Democrats, but he saw the proposed $400 billion program as an opportunity that should not be missed. However, when the final formulation of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act contained provisions to steer seniors towards private plans, Kennedy switched to opposing it. It passed in late 2003, and led Kennedy to again say he had been betrayed by the Bush administration.

After Bush won a second term in the 2004 general election, Kennedy continued to oppose him on Iraq and many other issues. However, Kennedy sought to partner with Republicans again on the matter of immigration reform in the context of the ongoing United States immigration debate. Kennedy was chair of the United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security, and Refugees, and in 2005, Kennedy teamed with Republican Senator John McCain on the Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act. The "McCain-Kennedy bill" did not reach a Senate vote, but provided a template for further attempts at dealing comprehensively with legalization, guest worker programs, and border enforcement components. Kennedy returned again with the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, which was sponsored by an ideologically diverse, bipartisan group of senators[88] and had strong support from the Bush administration. The bill aroused furious grassroots opposition among talk radio listeners and others as an "amnesty" program,[89] and despite Kennedy's last-minute attempts to salvage it, failed a cloture vote in the Senate.[90] Kennedy was philosophical about the defeat, saying that it often took several attempts across multiple Congresses for this type of legislation to build enough momentum for passage.

Support for Obama

Kennedy remained neutral as the 2008 Democratic nomination battle between Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama intensified, because his friend Chris Dodd was also running for the nomination.[91] The initial caucuses and primaries were split between Clinton and Obama. When Dodd withdrew from the race, Kennedy became dissatisfied with the tone of the Clinton campaign and what he saw as racially tinged remarks by Bill Clinton [92] Kennedy gave an endorsement to Obama on January 28, 2008, despite appeals by both Clintons not to do so.[93] In a move that was seen as a symbolic passing of the torch, Kennedy said that it was "time again for a new generation of leadership," and compared Obama's ability to inspire with that of his fallen brothers.[92] In return, Kennedy gained a commitment from Obama to make universal health care a top priority of his administration if he were elected.[91] Kennedy's endorsement was considered among the most influential that any Democrat could get, and raised the possibility of improving Obama's vote-getting among unions, Hispanics, and traditional base Democrats.[93] It dominated the political news, and gave national exposure to a candidate who was still not well known in much of the country, as the Super Tuesday primaries across the nation approached.[94]

Illness and death

On May 17, 2008, Kennedy suffered a seizure, which was followed by a second seizure as he was being rushed from the Kennedy Compound to Cape Cod Hospital and then by helicopter to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Within days, doctors announced that Kennedy had a malignant glioma, a type of cancerous brain tumor. The grim diagnosis brought reactions of shock and prayer from many senators of both parties and from President Bush.[95]

Kennedy made his first post-illness public appearance on July 9, when he surprised the Senate by showing up to supply the added vote to break a Republican filibuster against a bill to preserve Medicare fees for doctors.[96] In addition, Kennedy was ill from an attack of kidney stones. Against the advice of some associates,[97] he insisted on appearing during the first night of the 2008 Democratic National Convention on August 25, 2008, where a video tribute to him was played. Introduced by his niece Caroline Kennedy, the senator said, "It is so wonderful to be here. Nothing – nothing – is going to keep me away from this special gathering tonight." He then delivered a speech to the delegates (which he had to memorize, as his impaired vision left him unable to read a teleprompter) in which, reminiscent of his speech at the 1980 Democratic National Convention, he said, "this November, the torch will be passed again to a new generation of Americans. So, with Barack Obama and for you and for me, our country will be committed to his cause. The work begins anew. The hope rises again. And the dream lives on."[98] The dramatic appearance and speech electrified the convention audience,[97] as Kennedy vowed that he would be present to see Obama inaugurated.[98]

On January 20, 2009, Kennedy attended Barack Obama's presidential inauguration, but then suffered a seizure at the luncheon immediately afterwards. He was taken by wheelchair from the Capitol building and then by ambulance to Washington Hospital Center. Doctors attributed the episode to "simple fatigue." He was released from the hospital the following morning, and he returned to his home in Washington, D.C.[99]

When the 111th Congress began, Kennedy dropped his spot on the Senate Judiciary Committee to focus all his attentions on national health care issues, which he regarded as "the cause of my life."[100] He saw the characteristics of the Obama administration and the Democratic majorities in Congress as representing the third and best great chance for universal health care, following the lost 1971 Nixon and 1993 Clinton opportunities, and as his last big legislative battle. He would not live to see the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Fifteen months after he was initially diagnosed with brain cancer, Kennedy succumbed to the disease on August 25, 2009, at age 77 at his home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. In a statement, Kennedy's family said:

We've lost the irreplaceable center of our family and joyous light in our lives, but the inspiration of his faith, optimism, and perseverance will live on in our hearts forever. He loved this country and devoted his life to serving it.[101]

When Kennedy died in August 2009, he was the second-most senior member of the Senate (after President pro tempore Robert Byrd of West Virginia) and the third longest-serving senator of all time, behind Byrd and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

When the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who was instrumental in doing so, credited Kennedy's life work in her closing remarks on the House floor before the final vote. Kennedy's widow Vicki attended the signing of the Act, at which both she and President Obama wore blue "Tedstrong" bracelets.[102] Congressman Patrick Kennedy brought a copy of a national health insurance bill his father had introduced in 1970 as a gift for the president.[102] Patrick Kennedy then laid a note on his father's grave that said, "Dad, the unfinished business is done."[103]

Legacy

During his tenure, Kennedy became one of the most recognizable and influential members of his party and was sometimes called a "Democratic icon"[104] as well as "The Lion of the Senate".[105] Kennedy and his Senate staff authored around 2,500 bills, of which more than 300 were enacted into law. Kennedy co-sponsored another 550 bills that became law after 1973. Kennedy was known for his effectiveness in dealing with Republican senators and administrations, sometimes to the irritation of other Democrats. During the 101st Congress under President George H. W. Bush, at least half of the successful proposals put forward by the Senate Democratic policy makers came out of Kennedy's Labor and Human Resources Committee.[106] During the 2000s, almost every bipartisan bill signed during the George W. Bush administration had significant involvement from Kennedy. A late 2000s survey of Republican senators ranked Kennedy first among Democrats in bipartisanship.[105] Kennedy strongly believed in the principle "never let the perfect be the enemy of the good," and would agree to pass legislation he viewed as incomplete or imperfect with the goal of improving it down the road. In May 2008, soon-to-be Republican presidential nominee John McCain said, "[Kennedy] is a legendary lawmaker and I have the highest respect for him. When we have worked together, he has been a skillful, fair and generous partner." Republican Governor of California and Kennedy relative by marriage Arnold Schwarzenegger described "Uncle Teddy" as "a liberal icon, a warrior for the less fortunate, a fierce advocate for health-care reform, a champion of social justice here and abroad" and "the rock of his family".[105]

After Robert Kennedy's assassination in 1968, Ted was the most prominent living member of the Kennedy family and the last surviving son of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. John F. Kennedy had said in 1957, "Just as I went into politics because Joe died, if anything happened to me tomorrow, my brother Bobby would run for my seat in the Senate. And if Bobby died, Teddy would take over for him."[107] However, Ted was never able to carry on the "Camelot" mystique in the same way that both of his fallen brothers had, with much of it disappearing during his failed 1980 presidential bid. His negligence in the death of Mary Jo Kopechne at Chappaquiddick and his well-documented later personal problems further tarnished his image in relation to the Kennedy name,[1] and significantly damaged his chances of ever becoming president.[2][48] The Associated Press wrote that, "Unlike his brothers, Edward M. Kennedy has grown old in public, his victories, defeats and human contradictions played out across the decades in the public glare."[108] But Kennedy's legislative accomplishments remained, and as The Boston Globe wrote, "By the early 21st century, the achievements of the younger brother would be enough to rival those of many presidents."[1]

Kennedy's New York Times obituary described him via a character sketch: "He was a Rabelaisian figure in the Senate and in life, instantly recognizable by his shock of white hair, his florid, oversize face, his booming Boston brogue, his powerful but pained stride. He was a celebrity, sometimes a self-parody, a hearty friend, an implacable foe, a man of large faith and large flaws, a melancholy character who persevered, drank deeply and sang loudly. He was a Kennedy."[2]

Awards and honors

Senator Kennedy received many awards and honors over the years. These include an honorary knighthood bestowed by Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, the Order of the Aztec Eagle from Mexico, the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Order of the Merit of Chile, and honorary degrees from a number of institutions including Harvard University.

Writings

- Kennedy, Edward M. (ed.). The Fruitful Bough (Collected essays on Joseph P. Kennedy). 1965.

- Kennedy, Edward M. Decisions for a Decade: Policies and Programs for the 1970s. Doubleday, 1968.

- Kennedy, Edward M. In Critical Condition: The Crisis in America's Health Care. Simon & Schuster, 1972. ISBN 978-0671213145

- Kennedy, Edward M. Our Day and Our Generation: The Words of Edward M. Kennedy. Simon & Schuster, 1979. ISBN 978-0671241339

- Kennedy, Edward M., and Mark Hatfield. Freeze!: How You Can Prevent Nuclear War. Bantam Books, 1982. ISBN 978-0553140774

- Kennedy, Edward M. America Back on Track. Viking Adult, 2006. ISBN 978-0670037643

- Kennedy, Edward M. My Senator and Me: A Dog's-Eye View of Washington, D.C. Scholastic Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0439650779

- Kennedy, Edward M. True Compass: A Memoir. Twelve, 2009. ISBN 978-0446539258

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Bella English, A childhood of privilege, promise, and pain The Boston Globe, February 15, 2009. Retrieved December 9 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 John M. Broder, Edward Kennedy, Senate Stalwart, Dies The New York Times, August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Martin F. Nolan, Kennedy dead at 77 The Boston Globe, August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Adam Clymer, Edward Kennedy: A Biography (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1999, ISBN 0688142850), 13, 16–17.

- ↑ Edward M. Kennedy, True Compass: A Memoir (New York, NY: Hachette Books 2009, ISBN 978-0446539258).

- ↑ James MacGregor Burns, Edward Kennedy and the Camelot Legacy (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 9780393331844), 36, 38–39, 352.

- ↑ Clymer, 11.

- ↑ Burns, 40–42, 57.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Clymer, 18–19.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 William J. Eaton, Charm And Image Overcame Errors As 'Prince' Rose Rapidly to Senate The Pittsburgh Press, June 18, 1968. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Joe McGinnis, The Last Brother, (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster 1993, ISBN 0671679457), 198.

- ↑ Burns, 46.

- ↑ Burns, 48–49.

- ↑ Burns, 50.

- ↑ Burns, 52.

- ↑ Burns, 50–51.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Burns, 53–54.

- ↑ Clymer, 25–27.

- ↑ Clymer, 23–24.

- ↑ Nellie Bly, The Kennedy Men:Three Generations of Sex, Scandal and Secrets, (New York, New York: Kensington Books, 1996 ISBN 1575661063.), 195.

- ↑ Clymer, 27–30.

- ↑ Per Article One of the United States Constitution.

- ↑ This was done so under the authority of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Massachusetts state law.

- ↑ Clymer, 43, 45–47.

- ↑ Clymer, 80–82.

- ↑ Clymer, 99–103.

- ↑ Neil Swidey, Turbulence and tragedies eclipse early triumphs Boston Globe, February 16, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Edward M. Kennedy Address at the Public Memorial Service for Robert F. Kennedy American Rhetoric: Top 100 Speeches. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Clymer, 141–142.

- ↑ Peter Evans, Ari: The Life and Times of Aristotle Onassis (New York, NY: Summit Books, 1986, ISBN 0671465082), 255. Kennedy has denied this; see Clymer, 130.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Jenna Russell, Conflicted ambitions, then, Chappaquiddick The Boston Globe, February 17, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Clymer, 131–132.

- ↑ Ronald Kessler, The Sins of the Father: Joseph P. Kennedy and the Dynasty He Founded (New York, NY: Warner Books, 1996, ISBN 0446518840), 419.

- ↑ Kennedy Stays in Senate; Will Seek New Term Toledo Blade, July 31, 1969. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Liz Trotta, Fighting for Air: In the Trenches With Television News (Columbia, MO: 1994, ISBN 0826209521), 184.

- ↑ Clymer, 245–250.

- ↑ Clymer, 252–256.

- ↑ Bernard Weinraub, Kennedy, Out of the Limelight, Is Content in Senate The New York Times, March 5, 1977. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Burton Hersh, The Shadow President: Ted Kennedy in Opposition (Lebanon, NH: Steerforth Press, 1997, ISBN 1883642302), 38.

- ↑ Clymer, 284–285.

- ↑ Hersh, 38–39.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 42.8 42.9 Sam Allis, Sailing into the Wind: Losing a quest for the top, finding a new freedom The Boston Globe, February 18, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Hersh, 45–47.

- ↑ Clymer, 294.

- ↑ Hersh, 50.

- ↑ Hedrick Smith, Carter's On-Job Rating Falls in Poll Because of Foreign Policy Concerns The New York Times, March 18, 1980. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Clymer, 303–304.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Michael Barone and Richard E. Cohen, The Almanac of American Politics, 2008 (National Journal Group, 2007, ISBN 978-0892341177), 792.

- ↑ Clymer, 309, 312.

- ↑ Clymer, 316–319.

- ↑ Ted Kennedy: 1980 Democratic National Convention Address American Rhetoric Top 100 Speeches. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ David C. Lewin (ed.), Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations: A research annual (Greenwich, CT: JAI, 1987, ISBN 0892329092).

- ↑ Clymer, 159–160, 173.

- ↑ Clymer, 187

- ↑ Clymer, 198–199.

- ↑ Clymer, 199–200.

- ↑ Clymer, 217–219.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Jonas Morris, Searching for a Cure: National health policy considered (New York, NY: Pica Press, 1984, ISBN 0876637411).

- ↑ Clymer, 276–278.

- ↑ Paul Starr, Remedy and Reaction: The peculiar American struggle over health care reform (Yale University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0300189155).

- ↑ Jimmy Carter, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President (Bantam Books, 1982, ISBN 0553050230), 86–87.

- ↑ Ted Kennedy, True Compass: A Memoir (Twelve, 2009, ISBN 978-0446539258).

- ↑ Clymer, 570.

- ↑ Robert Pear, Hatch Joins Kennedy to Back a Health Program The New York Times, March 14, 1997. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ↑ Clymer, 212–215.

- ↑ Clymer, 270, 273–274.

- ↑ U.S. diplomatic cable on Kennedy's visit to Hiroshima. U.S. Department of State, January 30, 1978; and U.S. diplomatic cable containing the speech transcript. U.S. Department of State, January 10, 1978. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Kennedy Denounces Reagan for 'Voodoo Arms Control' The New York Times, June 22, 1982. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Hedrick Smith, Reagan Finds a Lesser Evil in Indefinite Recess of Talks The New York Times, December 9, 1983. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Peter Robinson, Ted Kennedy's Soviet Gambit Forbes, August 27, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Allen McDuffee, Teddy Kennedy used a secret message to get the Russians to intervene in Reagan's 1984 re-election Timeline, July 27, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Tim Sebastian, Teddy, the KGB and the top secret file The Sunday Times, February 2, 1992. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Hersh, 77–78.

- ↑ Clymer, 326.

- ↑ Clymer, 391–393.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Hersh, 73–75.

- ↑ David Ingram, Conservative U.S. jurist Robert Bork dies at 85 Reuters, December 19, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Segal, Amicus Curiae Briefs by the Solicitor General during the Warren and Burger Courts: A Research Note The Western Political Quarterly 41(1) (1988): 135-144.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Gail Russell Chaddock, Court nominees will trigger rapid response Christian Science Monitor, July 7, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Barone and Cohen, 364.

- ↑ Clymer, 495.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Clymer, 493–499.

- ↑ William Welch, 'Benefit of the Doubt' – Key Senators Give Thomas Support for Confirmation The Seattle Times, October 15, 1991. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Hersh, 155–158.

- ↑ Hersh, 163–164.

- ↑ Clymer, 578–581.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 W. James Antle III, Leaving No Child Left Behind The American Conservative, August 1, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 'Gang of 12' mulls over immigration bill NBC News, May 24, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Julia Preston, Grass Roots Roared and Immigration Plan Collapsed The New York Times, July 10, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Carl Hulse, Kennedy Plea Was Last Gasp for Immigration Bill The New York Times, June 9, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Dan Balz and Haynes Johnson, How Obama Snared the Lion of the Senate The Washington Post, August 3, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Jeff Zeleny, Kennedy Calls Obama 'New Generation of Leadership' The New York Times, January 28, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Jeff Zeleny and Carl Hulse, Kennedy Chooses Obama, Spurning Plea by Clintons The New York Times, January 28, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Richard Wolffe, Renegade: The Making of a President (New York, NY: Crown Publishers, 2009, ISBN 978-0307463128), 200–201.

- ↑ Kennedy diagnosed with malignant brain tumor NBC News, May 20, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Carl Hulse and Robert Pear, Kennedy's Surprise Return Helps Democrats Win the Day The New York Times, July 10, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Kennedy electrifies Democratic convention with appearance CNN, August 25, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Marcus Baram, Kennedy Rallies Dems With Fiery Speech ABC News, August 25, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Senator Kennedy leaves hospital BBC News, January 20, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Ann Gerhart and Dan Balz, Kennedy Did His Life's Work Until the End The Washington Post, August 27, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Ted Kennedy Dies of Brain Cancer at Age 77 ABC News, August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Robert Pear, Obama Signs Health Care Overhaul Bill, With a Flourish The New York Times, March 23, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Philip Rucker and Eli Saslow, 'Dad, the unfinished business is done' NBC News, March 23, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Gail Russell Chaddock, Democratic primary: Quiet battle for the other delegates The Christian Science Monitor, January 30, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 Arnold Schwarzenegger, The 2009 TIME 100: Edward Kennedy TIME, April 30, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Hersh, 82.

- ↑ The Campaign: Pride of the Clan TIME, July 11, 1960. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ Kennedy's life plays out in public Associated Press, May 25, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, Bill. The Wit and Wisdom of Ted Kennedy. Pegasus Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1605981123

- Allen, Gary. Ted Kennedy: In Over His Head. Conservative Press, 1980. ISBN 0892450207

- Barone, Michael and Richard E. Cohen. The Almanac of American Politics, 2008. National Journal Group, 2007. ISBN 978-0892341177

- Bly, Nellie. The Kennedy Men: Three Generations of Sex, Scandal and Secrets. Kensington Books, 1996. ISBN 1575661063

- Burke, Richard E. The Senator: My Ten Years With Ted Kennedy. St. Martin's Press, 1993. ISBN 0312951337

- Burns, James MacGregor. Edward Kennedy and the Camelot Legacy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 9780393331844

- Canellos, Peter S. (ed.) The Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy. Simon & Schuster, 2009. ISBN 978-1439138175

- Carter, Jimmy. Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President. Bantam Books, 1982. ISBN 0553050230

- Clymer, Adam. Edward M. Kennedy: A Biography. Wm. Morrow & Company, 1999. ISBN 0688142850

- Damore, Leo. Senatorial Privilege: The Chappaquiddick Cover-Up. Regnery Gateway, 1988. ISBN 0895265648

- David, Lester. Ted Kennedy: Triumphs and Tragedies. New York, NY: Grosset & Dunlap, 1972. ISBN 978-0448017679

- David, Lester. Good Ted, Bad Ted: The Two Faces of Edward M. Kennedy. Carol Publishing Corporation, 1993. ISBN 1559721677

- Evans, Peter. Ari: The Life and Times of Aristotle Onassis (New York, NY: Summit Books, 1986, ISBN 0671465082. Ari: The Life and Times of Aristotle Onassis. New York, NY: Summit Books, 1986. ISBN 0671465082

- Hersh, Burton. The Education of Edward Kennedy: A Family Biography. New York, NY: Wm. Morrow & Company, 1972. ISBN 978-0688000752

- Hersh, Burton. The Shadow President: Ted Kennedy in Opposition. Steerforth Press, 1997. ISBN 1883642302

- Hersh, Burton. Edward Kennedy: An Intimate Biography. Counterpoint, 2010 ISBN 978-1582436289

- Honan, William H. Ted Kennedy: Profile of a Survivor. New York, NY: Quadrangle Books, 1972. ISBN 978-0532121305

- Kessler, Ronald. The Sins of the Father: Joseph P. Kennedy and the Dynasty He Founded. New York, NNY: Warner Books, 1996. ISBN 0446518840

- Klein, Edward. Ted Kennedy: The Dream That Never Died. Crown Publishing Group, 2009. ISBN 978-0307451033

- Leamer, Laurence. The Kennedy Men: 1901–1963. Wm. Morrow & Company, 2001. ISBN 0688163157

- Leamer, Laurence. Sons of Camelot: The Fate of an American Dynasty. Wm. Morrow & Company, 2004. ISBN 006620965X

- Lewin, David C. (ed.). Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations: A research annual. Greenwich, CT: JAI, 1987. ISBN 0892329092

- Lerner, Max. Ted and the Kennedy Legend: A Study in Character and Destiny. St Martins Press, 1980. ISBN 0312790430

- Levin, Murray. Edward Kennedy: The Myth of Leadership. Houghton Mifflin, 1980. ISBN 0395292492

- Lippman, Theo Jr. Senator Ted Kennedy: The Career Behind the Image. W. W. Norton & Company, 1976. ISBN 0393335267

- McGinnis, Joe. The Last Brother. Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 0671679457

- Morris, Jonas. Searching for a Cure: National health policy considered. New York, NY: Pica Press, 1984. ISBN 0876637411

- Rust, Zad. Teddy Bare: The Last of the Kennedy Clan. Belmont, MA: Western Islands, 1971. ISBN 978-0882791098

- Starr, Paul. Remedy and Reaction: The peculiar American struggle over health care reform. Yale University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0300189155

- Trotta, Liz. Fighting for Air: In the Trenches With Television News. Columbia, MO: 1994. ISBN 0826209521

- Wolffe, Richard. Renegade: The Making of a President. New York, NY: Crown Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-0307463128

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Senator Edward M. Kennedy 1932 - 2009

- Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate

- FBI Records: The Vault - Senator Edward Moore “Ted” Kennedy

- Ted Kennedy Find a Grave

| Party Political Offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: John F. Kennedy |

Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (Class 1) 1962, 1964, 1970, 1976, 1982, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006 |

Succeeded by: Martha Coakley |

| Preceded by: Russell B. Long |

Senate Democratic Whip 1969–1971 |

Succeeded by: Robert Byrd |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by: Benjamin A. Smith II |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Massachusetts 1962–2009 Served alongside: Leverett Saltonstall, Edward Brooke, Paul Tsongas, John Kerry |

Succeeded by: Paul G. Kirk |

| Preceded by: Russell B. Long |

Senate Majority Whip 1969–1971 |

Succeeded by: Robert Byrd |

| Preceded by: James Eastland |

Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee 1978–1981 |

Succeeded by: Strom Thurmond |

| Preceded by: Orrin Hatch |

Chair of the Senate Labor Committee 1987–1995 |

Succeeded by: Nancy Kassebaum |

| Preceded by: Jim Jeffords |

Chair of the Senate Health Committee 2001–2003 |

Succeeded by: Judd Gregg |

| Preceded by: Mike Enzi |

Chair of the Senate Health Committee 2007–2009 |

Succeeded by: Tom Harkin |

| Honorary Titles | ||

| Preceded by: Maurice J. Murphy Jr. |

Baby of the Senate 1962–1969 |

Succeeded by: Bob Packwood |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.