The word oratory refers to the art of eloquent speech. An orator is one who practices oratory or speaks in public. Many undergo extensive training to maximize their talent in this area as oratory is an effective tool of persuasion. Effective oratory is a useful tool in law, politics, ceremonies, and religion among other social situations. However, when the motivation of the orator is self-centered rather than righteous and in the interest of society as a whole, oratory can be a dangerous tool leading to evil consequences. As Cicero (106 - 43 B.C.E.) noted long ago, it is best if skilled orators also manifest the best human qualities, leading their audience to live for the sake of others and thus to develop the best possible human society.

Etymology

The term Orator is recorded in English since around 1374, meaning "one who pleads or argues for a cause," from Anglo-French oratour, from Old French orateur, from Latin orator "speaker," from orare "speak before a court or assembly, plead," from a Proto-IndoEuropean base "to pronounce a ritual formula." The modern meaning "public speaker" is attested from approximately 1430.

The derived word "oration," originally used for prayer since 1375, now means (recorded since 1502) any formal speech, as on a ceremonial occasion or delivered in similar pompous manner. The term "Pulpit orator" denotes Christian authors, often clergymen, who are renowned for their ability to write and/or deliver (from the pulpit in church) rhetorically skilled religious sermons.

In the Roman Catholic Church, an "oratory" also refers to a semi-public place of worship constructed for the benefit of a group of persons.

History

In ancient Greece and Rome, oratory was studied as a component of rhetoric (that is, composition and delivery of speeches), and was an important skill in public and private life. Aristotle (384 B.C.E. – 322 B.C.E.) and Quintilian (c. 35 C.E.–c. 100 C.E.) both discussed oratory. In ancient Rome, the art of speaking in public (Ars Oratoria) was a professional competence especially cultivated by politicians and lawyers. As the Greeks were still seen as the masters in this field, as in philosophy and most sciences, the leading Roman families often sent their sons to study under a famous master in Greece (as was the case with the young Julius Caesar) or engaged a Greek teacher (under pay or as a slave).

Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.E.), lawyer, statesman, philosopher, and writer who lived during the most brilliant era of Roman public life, is considered one of the greatest of the Latin orators and prose writers. Among his writings can be found his views on oratory. On the Orator contains discussions of the nature of law, philosophy, and rhetoric, and the relationships among them. Cicero gives rhetoric more importance than law and philosophy, arguing that the ideal orator would have mastered both and would add eloquence besides. He regretted that philosophy and rhetoric were no longer taught together, as they were in the old days.

Cicero suggested that the best orator should be the best human being, understanding the correct way to live, acting upon it by being active in politics, and instructing others through speeches, through example, and through making good laws. The Orator is a letter written in defense of Cicero’s own style of oratory. It describes the qualities of a good orator, who must be able to persuade his audience, entertain them, and arouse their emotions.

As the Romans adopted and modified the Greek art of public speaking, they developed a different style, which was regarded by some as a loss of content:

[O]ratory suffered severely after the Latin power ascension, for public speech can only be developed in ambients where debate is allowed. Hence, inside a Roman regime, where the very essence of man was to live as a State appendices (and not debate it), oratory fast became a mere compendium on "how to speak fluently" (focus on the beauty of the exposition), even though without any content (preferably without content, since it requires critical thinking).[1]

The distinctive features of the Latin and Greek forms of oratory can be summarized as follows:

- Latin: Strong valorization of form. Remarkable use of stylistics. Constant appeal to the listener emotions. Communication is deemed as a way to demonstrate "intellectual superiority" or eloquence.

- Greek: Strong valorization of message content. Utilization of argumentation strategies. Appeal to the common sense. Communication is deemed as skill to persuade and obtain influence.

Oratory, with definitive rules and models, was emphasized as a part of a "complete education" during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, although this was generally confined to the church. The development of parliamentary systems in Europe saw the rise of great political orators; the ability to wield words effectively became one of the chief tools of politicians, and often made the greatest difference in their positions. William Ewart Gladstone (1809 – 1898), one of the greatest British prime ministers, was a formidable orator:

Remember the rights of the savage, as we call him. Remember that the happiness of his humble home, remember that the sanctity of life in the hill villages of Afghanistan among the winter snows, are as sacred in the eye of Almighty God as are your own. Remember that He who has united you together as human beings in the same flesh and blood, has bound you by the law of mutual love, that that mutual love is not limited by the shores of this island, is not limited by the boundaries of Christian civilization, that it passes over the whole surface of the earth, and embraces the meanest along with the greatest in its wide scope.[2]

The Gettysburg Address by U. S. President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most quoted speeches in United States history. It was delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on November 19, 1863, during the American Civil War, four and a half months after the Battle of Gettysburg that turned the tide of the war irrevocably toward the Union side. Beginning with the now-iconic phrase "Four score and seven years ago," Lincoln referred to the events of the American Revolutionary War and described the ceremony at Gettysburg as an opportunity not only to dedicate the grounds of a cemetery, but also to consecrate the living in the struggle to ensure that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

World War II, a historical moment where democratic ideals began to take body in the world, saw a gradual deprecation of the old Latin style of communication which focused on formalism. By the mid twentieth century, oratory became less grandiloquent and more conversational; for instance, the "fireside chats" of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Despite following this more conversational style, as president in the late twentieth century, Ronald Reagan also used his communication skills to challenge the legitimacy of the Soviet Union, calling it "the evil empire," and to restore America's national pride. He used strong, even ideological language to condemn communism during his first term, but he could also evoke optimistic ideals of the United States as a defender of liberty. Speeches recalled America as the "shining city on a hill," "big-hearted, idealistic, daring, decent, and fair," whose citizens had the "right to dream heroic dreams."[3][4]

In response to being dubbed the Great Communicator, Reagan said in his Farewell Address:

I never thought it was my style or the words I used that made a difference: It was the content. I wasn't a great communicator, but I communicated great things.[5]

Uses

Oratory has been used to great effect in many avenues of human society. Of particular note are law, politics, and religion. Also, formal ceremonies provide an opportunity for orators to use their skills to address the public.

Law

Oratory is a vital component in the modern legal system. Cases are decided on the strength of the argument of either side's attorneys (for the prosecution or plaintiff, or for the defense). Cases are book ended by opening and closing statements in which attorneys attempt to paint the facts in their client's interest. While one side might have fact on their side, they oftentimes lose should the other side have skilled orators capable of convincing a jury of their story. Oratory in court cases comes both from speaking skills and a deep knowledge of the law, used to highlight oftentimes seemingly minute points that can be spun into case-changing arguments depending on the skill of the orator. Some famous examples of effective oratory in court cases include that of Clarence Darrow, who was able to avert the death penalty in the case of Leopold and Loeb, and Johnnie L. Cochran who employed catchy sayings such as "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit" in the murder trial of former football star and actor O. J. Simpson.[6]

Politics

Oratory can also make or break political careers. Politicians with polished oratory skills have been able to sway the public or other politicians over key issues and build popular support for their side. Thomas Hart Benton was a famously brilliant orator who helped stave off the Civil War with his speeches in the Senate. Adolf Hitler is an example of a politician whose political goals were accomplished through effective oratory to the public. His fascist reign depended on his ability to convince the German people of the viability of his plans. Widely regarded as a master orator, his speeches had an almost hypnotic power, beginning very slowly and gradually building up to an almost ecstatic and frenzied climax with the massive audiences ready to follow his leadership blindly.

Also playing an important role in World War II was Winston Churchill, whose speeches salvaged the morale of the British people and ultimately helped sustain them throughout the war.

Dubbed "The Great Communicator," Ronald Reagan was known for his ability to express ideas and emotions in an almost personal manner, even when making a formal address. Reagan honed these skills as a radio host, actor, live television host, and politician. As a young man, he was inspired by Roosevelt's attacks on Nazi Germany and spirited defense of democracy. He emulated his speaking style, even swinging around a cigarette holder as he talked.[7] In his autobiography, Reagan warmly recounted Roosevelt's fireside chats, and wrote that he borrowed from his playbook when he took his case directly to the American people.

Oratory gives otherwise inexperienced politicians the chance to shine, as was the case with Barack Obama at the 2004 National Democratic Convention. After this convention Obama was catapulted into the Democratic Party's spotlight as a potential presidential candidate. Similarly, John F. Kennedy launched his ascent to the presidency through his charismatic oratory. He overcame criticism of being too young and politically inexperienced through a series of brilliant speeches and debates.

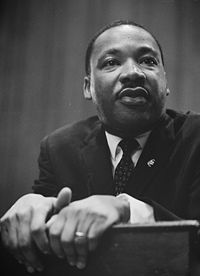

Political activists outside of government have used oratory to much good as well. Martin Luther King was a great orator whose famous speeches, such as "I have a dream," changed the nation by rallying people of every color to a common cause. An equally gifted speaker for the civil rights movement was Malcolm X.

Religion

Religion has long been associated with the most intelligent and educated figures in society; America's Ivy League schools have religious origins. Thus it is not surprising that some of the greatest speakers in history have been religious figures.

Religious oratory is often used for proselytizing non-believers, but is also used to fire up the faithful base of believers. Two of the most important figures in today's religions are Jesus and Muhammad, both of whom were known as great speakers. The power of these men to convince oftentimes hostile audiences of the validity of their messages is testament to their skills as speakers. Jesus' "Sermon on the Mount" continues to be quoted today.

Preachers often used their pulpits as opportunities to present religious views that opposed the mainstream. Leaders of the Protestant Reformation, such as Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, and John Calvin preached strongly and eloquently for change. Hugh Latimer was a famous Protestant martyr, killed for his reformist preaching at Cambridge University. During King Henry VIII's reign he was twice imprisoned in the Tower of London (1539 and 1546). During the reign of Henry's son Edward VI, he was restored to favor as the English church moved in a more Protestant direction. However, when Edward's sister Queen Mary I came to the throne, he was tried for his beliefs and preaching, imprisoned, and sentenced to death. In October 1555 he was burned at the stake outside Balliol College, Oxford.

Members of the Jesuit order used then-modern skills of persuasion to convert many of the Native Americans, Chinese, and Indians to Catholicism on missions.[8] Father António Vieira was a Portuguese Jesuit and writer, the "prince" of Catholic pulpit-orators of his time. In 1635 he received the priesthood. He soon began to distinguish himself as an orator, and the three patriotic sermons he delivered at Bahia (1638–1640) are remarkable for their imaginative power and dignity of language. The sermon for the success of the arms of Portugal against Holland was considered by the Abbé Raynal to be "perhaps the most extraordinary discourse ever heard from a Christian pulpit."

In American history were the periods known as the Great Awakening in the 1700s, during which more fundamentalist forms of Protestantism took hold in America thanks to the efforts of powerful public speakers from Baptist, Methodist, and other churches. The Great Awakening led to a wave of religious fervor. Continuing in that fundamentalist Christian vein two hundred years later, speakers such as Billy Graham and Pat Robertson helped to make evangelical Christianity one of the most popular forms of religion in the country.[9]

Ceremony

Important ceremonies are often marked by great uses of oratory. A funeral oration or epitaphios logos (Greek: ἐπιτάφιος λόγος) is a formal speech delivered on the ceremonial occasion of a funeral. In ancient Greece and, in particular, in ancient Athens, the funeral oration was deemed an indispensable component of the funeral ritual.

In Homer's writings very few formal elements of the epitaphios logos are found. At the funeral of Hector the women deliver the final public statements over the dead body.[10] Andromache laments the loss of her husband with these emotional words:

Woe is me, O Hector; woe, indeed, that to share a common lot we were born, you at Troy in the house of Priam, and I at Thebes under the wooded mountain of Plakos in the house of Eetion who brought me up when I was a child - ill-starred sire of an ill-starred daughter - would that he had never begotten me. You are now going into the house of Hades under the secret places of the earth, and you leave me a sorrowing widow in your house. The child, of whom you and I are the unhappy parents, is as yet a mere infant. Now that you are gone, O Hector, you can do nothing for him nor he for you.[11]

It was established Athenian practice by the late fifth century to hold a public funeral in honor of all those who had died in war to benefit Athens. The main part of the ceremony was a speech delivered by a prominent Athenian citizen. Pericles' "Funeral Oration" is a famous speech from Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War,[12] reputedly delivered by Pericles, an eminent Athenian politician of the 400s B.C.E. and the guiding force in Athens during the early Peloponnesian War. Historically, the speech is significant because the speech goes well beyond the typical formula of praising the glorious dead. David Cartwright describes it as "a eulogy of Athens itself."[13] The speech is a glorification of Athens' achievements, designed to stir the spirits of a state still at war.

Parallels between Pericles' funeral oration and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address have been noted.[14] Pericles' speech, as did Lincoln's, began with an acknowledgment of revered predecessors: "I shall begin with our ancestors: it is both just and proper that they should have the honor of the first mention on an occasion like the present," then praises the uniqueness of the State's commitment to democracy: "If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences," honors the sacrifice of the slain, "Thus choosing to die resisting, rather than to live submitting, they fled only from dishonor, but met danger face to face," and exhorts the living to continue the struggle: "You, their survivors, must determine to have as unfaltering a resolution in the field, though you may pray that it may have a happier issue."[12]

Training

While many notable orators appear to have a natural ability to speak persuasively to a large audience, such skills require significant effort and training. Many people list speaking in public as their greatest fear; it ranks higher than the fear of death for many individuals. Clinically, such fear is known as "Glossophobia."

Demosthenes (384 – 322 B.C.E.) was a prominent statesman and orator of Ancient Greece. As a boy, however, Demosthenes suffered from a speech impediment, an inarticulate and stammering pronunciation. According to Plutarch, he also had a weakness in his voice, "a perplexed and indistinct utterance and a shortness of breath, which, by breaking and disjointing his sentences much obscured the sense and meaning of what he spoke." Undeterred, Demosthenes undertook a disciplined program to overcome these shortcomings and improve his locution. He worked on his diction, his voice, and his gestures.[15] His zeal and perseverance have passed into proverb.

Students of oratory are assigned exercises to improve their speaking skills. They learn by observation of skilled orators, live or recorded. Practice is also essential, as well as receiving feedback. Self-observation is a valuable tool, accomplished by speaking to a mirror, or by viewing a recording of one's speech. Honing one's skills is best accomplished by listening to constructive suggestions followed by new public speaking exercises. These include:

- The use of gestures

- Control of the voice

- Choice of vocabulary

- Speaking notes

- Using humor

- Developing a relationship with the audience, through eye-contact

The teaching and learning of the two forms of oratory (Latin and Greek) differ, due to the differences in their style. Thus the demands upon both teachers and students are different:

Teachers:

- Latin Oratory, because it is merely formal, is easy to teach.

- Greek Oratory, for it demands much more in terms of content, requires (from the masters) an extraordinarily superior formation (philosophy, logic, ethics, stylistics, grammar, and so forth), since it is not acceptable that a Master could be defeated by his/her disciples. Therefore, while teachers of Latin Oratory are just any person who delivers speeches with fluency, to train a teacher of Greek oratory could take years of study and deep meditation.

Students:

- Latin Oratory can be taught through relatively fast courses.

- Greek Oratory demands much more time and effort.

In the twenty-first century there has been a vigorous tendency to return to the "Greek School of Oratory" (Aristotelian), since the modern world does not accept, as it did in the past, "fluent speeches" without any content.

Notes

- ↑ Iran Necho, Oratory Course Instituto Moreira Necho. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ↑ William Ewart Gladstone, Mr. Gladstone's visit to Mid-Lothian: Meeting at the Foresters' Hall. 1879.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan's second Inaugural address (1985) Reagan Foundation. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan's first Inaugural address (1981) Reagan Foundation.org. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Farewell Address (1989). Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Simpson tries on bloody gloves CNN interactive, 1995.

- ↑ Douglas Brinkley, The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day, and the U.S. Army 2nd Ranger Battalion. (William Morrow & Co, 2005, ISBN 0060759348).

- ↑ Francois Roustang, The Jesuit Missionaries to North America. (Ignatius Press, 2006, ISBN 158617083X).

- ↑ George W. Dollar, A History of Fundamentalism in America. (Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 1973).

- ↑ H. P. Foley, Female Acts in Greek Tragedy (Princeton University Press, 2002, ISBN 0691094926).

- ↑ Homer, The Iliad. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pericles' Funeral Oration from Thucydides Peloponnesian War.

- ↑ David Cartwright, A Historical Commentary On Thucydides (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997, ISBN 0472084194).

- ↑ James McPherson, "The Art of Abraham Lincoln." The New York Review of Books. 1992. Retrieved January 18, 2005

- ↑ Plutarch, Demosthenes.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barringer, Judith M., and Jeffrey Hurwit. Periklean Athens And Its Legacy. University of Texas Press, 2005. ISBN 0292706227.

- Brinkley, Douglas. The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day, and the U.S. Army 2nd Ranger Battalion. William Morrow & Co, 2005. ISBN 0060759348.

- Cartwright, David. A Historical Commentary On Thucydides. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ISBN 0472084194

- Cicero. De Legibus.thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Colaiaco, James A. Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial. Routledge UK, 2001. ISBN 0415926548.

- Demosthenes. Against Leptines. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Derderian, Katharine. Leaving Words to Remember. Brill Academic Publishers, 2000. ISBN 9004117504.

- Diogenes Laertius. Solon.

- Dollar, George W. A History of Fundamentalism in America. Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 1973.

- Foley, Helene P. Female Acts in Greek Tragedy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002. ISBN 0691094926.

- Homer. Iliad Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Loraux, Nicole. The Children of Athena. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994. ISBN 0691037620.

- Loraux, Nicole. The Invention of Athens: The Funeral Oration in the Classical City. Zone Books, 2006. ISBN 1890951595

- McPherson, James. "The Art of Abraham Lincoln," The New York Review of Books. Volume 39, Number 13, July 16, 1992. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- Monoson, Sara. Plato's Democratic Entanglements. Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0691043663.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Pindar. Sixth Olympian For Hagesias of Syracuse Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Plato. Menexenus Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Plutarch. Demosthenes Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Roustang, Francois. The Jesuit Missionaries to North America. Ignatius Press, 2006. ISBN 158617083X

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War (II). Retrieved November 9, 2015.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- CSA - Celebrity Speakers: Top speakers' Bureau for Central & Eastern Europe

- CSA - Celebrity Speakers: Leading European Speakers' Bureau

- How to Conquer America's Greatest Fear: The Fear of Public Speaking

- Greater Talent Network, America's Leading Celebrity Speakers Bureau

- National Speakers Association (NSA)

- ICMI Speakers Bureau

- Saxton Speakers Bureau: Australia's leading public speaking bureau

- Speakers Corner

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Oratory history

- Orator history

- Public_speaking history

- Public_speaker history

- Funeral_oration_(ancient_Greece) history

- Pericles'_Funeral_Oration history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.