Eugene Delacroix

| Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix |

|---|

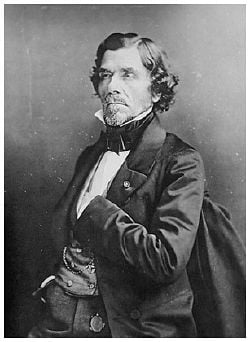

Eugène Delacroix (portrait by Nadar)

|

| Born |

| April 26, 1798 Charenton-Saint-Maurice, Île-de-France, France |

| Died |

| August 13, 1863 Paris, France |

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix (April 26, 1798 – August 13, 1863) is often considered the most important of the French Romantic painters. Delacroix's use of expressive brushstrokes and his study of the optical effects of color profoundly shaped the work of the Impressionists, while his passion for the exotic inspired the artists of the Symbolist movement.

Although steeped in classical training, his brilliant and innovative use of color, exotic locales, and provocative subject matter served as inspiration to younger artists who were breaking with more formal traditions in art. Among French painters he is considered the greatest colorist and was said to influence even modern artists such as Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh. Paul Cezanne speaking of Delacroix's far reaching legacy, once remarked, "We are all in Delacroix."[1]

A skillful writer, his journals have also been recognized as an important record of the artists' life and work during this era.

Early life and art education

Delacroix was born at Charenton-Saint-Maurice, in the Île de France région near Paris, France.

It has often been theorized that his father, Charles Delacroix, was infertile at the time of Eugène's conception and that his real father was the French diplomat Talleyrand, whom he resembled in appearance as an adult.[2] His early schooling was completed at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, France's rigorous public high school. He received an orthodox education, studying Homer, Virgil and the French classics including Voltaire. His love of literature, particularly of Shakespeare's dramas and Lord Byron's poetry would serve as inspiration for many of his artistic works.

In 1815 he began his training at the studio of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin imitating the neoclassical style of Jacques-Louis David. Later that year he attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he learned to paint history, allegory and myth in the manner of the Old Masters. Howevever, he was to be strongly influenced by the more colorful style of the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and fellow French artist Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) whose works marked an introduction to romanticism in art.

In 1822, his first major painting, Bark of Dante, was accepted by the Paris Salon, praised by the critics, and bought by the state. In this dramatic picture the Latin poet, Virgil is guiding Dante through the underworld, while doomed souls struggle to climb aboard their boat. Its study of figures owes a debt to notable Renaissance artist, Michelangelo but its genius is entirely Delacroix's.[2]

Chios and Missolonghi

Two years later, at the age of 24, he earned celebrity with his painting Massacre at Chios. Although a controversial picture due to its brutality, it was also well regarded by many French people who were in sympathy with the Greeks, engaged at that time in a war of independence from the Turks. The painting of the Massacre at Chios (also called Massacre at Scio, French: Scènes des massacres de Scio), shows sick, dying Greek civilians about to be slaughtered.

After the completion of Chios, Delacroix gained recognition as a leading painter in the new Romantic style. His depiction of suffering was controversial, however, as there was no glorious event taking place, no patriots raising their swords in valor as in David's Oath of the Horatii. There was only a disaster, without a conquering hero in the vein of the classics. Many critics deplored the painting's despairing tone; one called it "a massacre of art."[2]The pathos in the depiction of an infant clutching its dead mother's breast had an especially powerful effect, although it was condemned as unfit for art by Delacroix's critics.

In 1827, Delacroix painted a second painting in support of the Greeks in their war of independence. Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi shows a woman in Greek attire with her arms raised in a powerless gesture towards a horrible scene: the mass suicide of Greeks, who chose to kill themselves and destroy their city rather than surrender to the Turks. A hand is seen at the bottom, the body having being crushed by the rubble of the city. The painting serves as a monument to the people of Missolonghi and to the idea of freedom from tyranny. This event held particular interest for Delacroix because of his sympathy for the Greek cause; their homeland was revered by many French at that time as the birthplace of classical tradition. Missolonghi is also where Lord Byron died after going there to support the Greeks in their War of Independence.

Death of Sardanapalus

Delacroix's painting of the death of the Assyrian king Sardanapalus shows an emotionally stirring scene alive with beautiful colors, exotic costumes and tragic occurrences. The Death of Sardanapalus depicts the besieged king watching impassively as guards carry out his orders to kill his servants, concubines, and animals in order to escape the world's madness.[2]

The picture was greeted once again by controversy due to its alarming subject matter and even Delacroix referred to it as "Massacre number two."[2] However, despite the scandal that it ignited the work shows the many risks that Delacroix took as an artist: there is a sense of unity with his brush strokes and colors—no one object stands out—and, despite its profusion of detail, its composition is organized and its color is radiant.

Sardanapalus' attitude of calm detachment is a familiar one in Romantic imagery in this period in Europe. The painting, which was not exhibited again for many years afterward, has been regarded by some critics as a gruesome display of death and lust. Especially shocking is the struggle of a nude woman whose throat is about to be cut, a scene placed prominently in the foreground for maximum effect. However, the sensuous beauty and exotic colors of the composition make the picture appear simultaneously tranquil and scintillating.

Liberty leading the people

Delacroix's most influential work, completed in 1830 and displayed at the 1831 Salon was the painting Liberty Leading the People. In terms of both subject matter and technique it highlights the marked differences that were evolving between the romantic approach of Delacroix and the neoclassical style of one of his most important forerunners, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

Probably Delacroix's best known painting, it is a striking image of Parisians, having taken up arms, marching forward under the banner of the Flag of France representing liberty and freedom. Delacroix, although notably apolitical, was inspired to invoke the romantic image of the spirit of liberty by the political turmoil happening in France at that time. "Liberty" is portrayed as part woman, part goddess showing more strength than femininity. The soldiers lying dead in the foreground offer a poignant juxtaposition to the symbolic female figure illuminated triumphantly in a shimmering cloud.

Rather than glorifying the actual revolution which overthrew King Charles X, Delacroix seems to have been trying to represent the spirit and the character of the people who, even after democratic reforms and long years of struggle, found themselves with another king when Louis-Philippe came to power.

The French government bought the painting but officials deemed its glorification of liberty too inflammatory and removed it from the public's view. Still, Delacroix continued to receive many government commissions for murals and ceiling paintings. Following the Revolution of 1848 and the end of the reign of King Louis Philippe, the painting, Liberty Leading the People, was finally put on display by the newly elected President, Napoleon III. Today, it can be viewed at the Louvre.

The boy holding a gun up on the right is sometimes thought to have been the inspiration for the Gavroche character in Victor Hugo's 1862 novel, Les Misérables.

Travel to North Africa

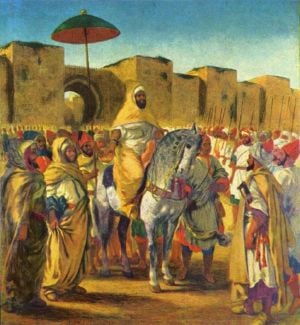

In 1832, Delacroix traveled to Spain and North Africa. While accompanying a diplomatic entourage, he visited Morocco where he was influenced by the people's exotic dress and customs, and even by the landscapes and architectural details. This trip would influence the subject matter and style of his future projects; he would continually incorporate motifs from his travels into his paintings, such as, fighting horses, whirling dervishes, and exotic costumes. Even the profusion of sunlight that he experienced in Morroco would affect the ambience and color of future paintings.

He felt that the North Africans, in their attire and their attitudes, provided a modern equivalent to how the people of Classical Rome and Greece would have looked. He managed to sketch some of the local women, as shown in the painting Women of Algiers (1834), but generally he experienced difficulty getting Moslem women to pose for him due to strict Moslem rules requiring women to be covered. Islamic art, which traditionally incorporates abstract designs and arabesques, has often disapproved of artistic renderings of the human form; therefore, Delacroix was sometimes forced to work in secret.

After an invitation to a Jewish wedding by a friend he was able to gain a rare and personal glimpse into the lives of Jews in North Africa whose posing was somewhat less problematic (Jewish Wedding in Morocco 1839).

While in Tangiers he made many sketches of the people and the city around him, and reserved these drawings for paintings which he would complete later after returning to France. In fact, he did over 100 paintings and drawings of scenes based on the life of the people of North Africa including Arab Horses Fighting in a Stable, The Lion Hunt and Moroccan Saddling his Horse.

Other Works

Delacroix was also a skilled draftsman and employed other techniques besides painting, such as: pencil, pen, wash, watercolor and lithography—a relatively new graphic process at that time.

He also illustrated various works of William Shakespeare, the Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott, and the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

His diary which he kept from 1823-1854 became an important commentary on the social, intellectual, and artistic world of Paris in the 1800s.

Throughout his life Delacroix painted religious subjects, and events from both history and literature. However, Romantics increasingly valued scenes of melancholy and solitude. Delacroix, in particular, seemed to be fascinated with the struggle between humanity and the forces of darkness and its accompanying bloodshed and violence.[3] He painted few still lifes or landscapes as the human drama was more captivating to him, however, he did paint portraits of friends such as the double portrait of composer Frédéric Chopin and writer George Sand. Although, the painting was subsequently cut the individual portraits survive.

From 1954-1955 Picasso painted 15 different versions of Women of Algiers some as monochromatic abstractions.

Delacroix on art

- ”What moves men of genius, or rather what inspires their work, is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough.”

- ”We need to be very bold. Without daring, without extreme daring even, there is no beauty... We must therefore be almost beyond ourselves if we are to achieve all that we are capable of.”

- ”To be understood a writer has to explain almost everything. In a painting, a mysterious bridge seems to exist between its painted subjects and the spectator's spirit.”

- ”Artists who seek perfection in everything are those who cannot attain it in anything.”

- ”Painting does not always need a subject.”

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts

In 1862 Delacroix helped to form a league of artists, the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. His friend, the writer Théophile Gautier, served as its first chairman. In addition to Delacroix, the committee was composed of the painters Carrier-Belleuse and Puvis de Chavannes. Among the exhibitors were Léon Bonnat, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Gustave Doré, and Edouard Manet. Just after his death in 1864, the society organized a retrospective exhibition of 248 paintings and lithographs by Delacroix, and then discontinued mounting any further exhibitions until 1890, when a revival of the group resulted in the sponsoring of annual exhibitions.

Eugène Delacroix died in Paris, France and was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

His house, formerly situated along the canal of the Marne, is now near the exit of the motorway leading from Paris to central Germany.

Gallery

"Frédéric Chopin" (1838, Louvre)

"George Sand" (1838, Ordrupgaardsamlingen, Ordrupgaard)

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Murray, Peter and Linda. Dictionary of Art and Artists. New York: Praeger, 1965.

- Osbourne, Harold (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Art. Great Britain: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Pool, Phoebe. Delacroix: 49 plates in Full Color. London: Hamlyn, 1969. ISBN 0600501515

- Prideaux, Tom. The World of Delacroix: 1798-1863. New York: Time Life Books, 1966.

External links

All links retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Home Page" Le Musée National Eugène Delacroix

- "Delacroix, Eugène" Web Gallery of Art

- "Delacroix, Eugène" WebMuseum

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

| Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - Słowacki - Wordsworth | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - Géricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.