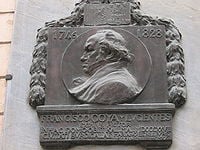

| Francisco Goya | |

Goya's self-portrait. | |

| Birth name | Francisco José De La Goya y Lucientes |

| Born | March 30, 1746 Fuendetodos |

| Died | April 16, 1828 Bordeaux |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Field | Painting, Printmaking |

| Famous works | La maja desnuda, 1797â1800 La maja vestida, 1800-05 The Second of May 1808, 1814 |

Francisco JosĂ© de Goya y Lucientes (March 30, 1746 â April 16, 1828) was a Spanish painter and printmaker.

Goya was a court painter to the Spanish Crown and a chronicler of history. He has been regarded both as the last of the Old Masters, (referring to those painters prior to 1800 who not only displayed great skill, but were also the head of a local artists' guild) and as the first of the moderns (from Romanticism on). His work was truly revolutionary in its implications. The subversive and subjective element in his art, as well as his bold handling of paint, provided a technical model for the work of later generations of artists, notably Manet and Picasso. As a larger cultural phenomenon, the rise of subjectivism is a hallmark of the modern age in every area. It came to be reflected in the art world through movements like the French Impressionists and later through Picasso, Salvador Dali and many others. The emphasis of self-development and self-expression reflects not only a greater importance attached to self-awareness, as well as a redefining of the boundaries and balance between notions of the private versus the public good.

Many of Goya's works are on display in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Biography

Early years

Francisco Goya was born in Fuendetodos, Spain, in the province of AragĂłn in 1746 to Joseph Goya and Gracia Lucientes. He spent his childhood in Fuendetodos, where his family lived in a house bearing the family crest of his mother. His father earned his living as a gilder. About 1749, the family bought a house in the city of Zaragoza and some years later moved into it.

Goya attended school at Escuelas Pias, where he formed a close friendship with Martin Zapater, and their correspondence over the years became valuable material for biographies of Goya. At age 14, he entered apprenticeship with the painter José Lujån.

He later moved to Madrid where he studied with Anton Raphael Mengs, a painter who was popular with Spanish royalty. He clashed with his master, and his examinations were unsatisfactory. Goya submitted entries for the Royal Academy of Fine Art in 1763 and 1766, but was denied entrance.

He then journeyed to Rome, where in 1771 he won second prize in a painting competition organized by the City of Parma. Later that year, he returned to Zaragoza and painted a part of the cupola of the Basilica of the Pillar, frescoes of the oratory of the cloisters of Aula Dei, and the frescoes of the Sobradiel Palace. He studied with Francisco Bayeu y SubĂas and his painting began to show signs of the delicate tonalities for which he became known.

Marriage and success

Goya married Bayeu's sister Josefa in 1773. His marriage to Josefa (he nicknamed her "Pepa"), and Francisco Bayeu's membership of the Royal Academy of Fine Artâhe had been a member since 1765âhelped him to procure work with the Royal Tapestry Workshop. There, over the course of five years, he designed some 42 patterns, many of which were used to decorate (and insulate) the bare stone walls of El Escorial and the Palacio Real de El Pardo, the newly built residences of the Spanish monarchs. This brought his artistic talents to the attention of the Spanish monarchs who later would give him access to the royal court. He also painted a canvas for the altar of the Church of San Francisco El Grande, which led to his appointment as a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Art.

In 1783, the Count of Floridablanca, a favorite of King Carlos III, commissioned him to paint his portrait. He also became friends with Crown Prince Don Luis, and lived in his house. His circle of patrons grew to include the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, whom he painted, the King and other notable people of the kingdom.

After the death of Charles III in 1788 and revolution in France in 1789, during the reign of Charles IV, Goya reached his peak of popularity with royalty.[1]

After contracting a high fever in 1792 Goya was left deaf, and he became withdrawn and introspective. During the five years he spent recuperating, he read a great deal about the French Revolution and its philosophy. The bitter series of aquatinted etchings that resulted were published in 1799 under the title Caprichos.

Painter of royalty

In 1799 he was appointed the Spanish royal painter with a salary of 50,000 reales and 500 ducats for a coach. He worked on the cupola of the Hermitage of San Antonio de la Florida; he painted the King and the Queen, royal family pictures, portraits of the Prince of the Peace and many other nobles. His portraits are notable for their disinclination to flatter, and in the case of The Family of Charles IV, the lack of visual diplomacy is remarkable:

Even if one takes into consideration the fact that Spanish portraiture is often realistic to the point of eccentricity, Goya's portrait still remains unique in its drastic description of human bankruptcy.[2]

Goya received orders from many friends within the Spanish nobility. Among those from whom he procured portrait commissions were Pedro de Ălcantara TĂ©llez-GirĂłn, 9th Duke of Osuna and his wife MarĂa Josefa de la Soledad, 9th Duchess of Osuna, MarĂa del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva y Ălvarez de Toledo, thirteenth Duchess of Alba (universally known simply as the "Duchess of Alba"), and her husband JosĂ© Ălvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga, thirteenth Duke of Alba, and MarĂa Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, Marchioness of Pontejos.

Later years and death

As French forces invaded Spain during the Peninsular War (1808â1814), the new Spanish court received him as had its predecessors.

When Pepa died in 1812, Goya was painting The Charge of the Mamelukes and The Third of May 1808, and preparing the series of prints known as The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra).

King Ferdinand VII came back to Spain but relations with Goya were not cordial. In 1814 Goya was living with his housekeeper Doña Leocadia and her illegitimate daughter, Rosario Weiss; the young woman studied painting with Goya, who may have been her father.[3] He continued to work incessantly on portraits, pictures of Santa Justa and Santa Rufina, lithographs, pictures of tauromachy, and more.

With the idea of isolating himself, he bought a house near Manzanares, which was known as the Quinta del Sordo (roughly, "House of the Deaf Man"). There he made the Black Paintings.

Unsettled and discontented, he left Spain in May 1824 for Bordeaux and Paris. He settled in Bordeaux. He returned to Spain in 1826 after another period of ill health. Despite a warm welcome, he returned to Bordeaux where he died in 1828 aged 82.

Works

Goya painted the Spanish royal family, including Charles IV of Spain and Ferdinand VII. His themes range from merry festivals for tapestry, draft cartoons, to scenes of war and corpses. This evolution reflects the darkening of his temper. Modern physicians suspect that the lead in his pigments poisoned him and caused his deafness after 1792. Near the end of his life, he became reclusive and produced frightening and obscure paintings of insanity, madness, and fantasy. The style of these Black Paintings prefigure the expressionist movement. He often painted himself into the foreground.

The Maja

Two of Goya's best known paintings are The Nude Maja (La maja desnuda) and The Clothed Maja (La maja vestida). They depict the same woman in the same pose, naked and clothed, respectively. He painted La maja vestida after outrage in Spanish society over the previous Desnuda. Without a pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning, the painting was "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art".[4] He refused to paint clothes on her, and instead created a new painting.

Darker realms

In a period of convalescence during 1793â1794, Goya completed a set of eleven small pictures painted on tin; the pictures known as Fantasy and Invention mark a change in his art. These paintings no longer represent the world of popular carnival, but rather a dark, dramatic realm of fantasy and nightmare.

Courtyard with Lunatics is a horrifying and imaginary vision of loneliness, fear and social alienation, a departure from the rather more superficial treatment of mental illness in the works of earlier artists such as Hogarth. In this painting, the ground, sealed by masonry blocks and iron gate, is occupied by patients and a single warden. The patients are variously staring, sitting, posturing, wrestling, grimacing or disciplining themselves. The top of the picture vanishes with sunlight, emphasizing the nightmarish scene below.

This picture can be read as an indictment of the widespread punitive treatment of the insane, who were confined with criminals, put in iron manacles, and subjected to physical punishment. And this intention is to be taken into consideration since one of the essential goals of the enlightenment was to reform the prisons and asylums, a subject common in the writings of Voltaire and others. The condemnation of brutality towards prisoners (whether they were criminals or insane) was the subject of many of Goyaâs later paintings.

As he completed this painting, Goya was himself undergoing a physical and mental breakdown. It was a few weeks after the French declaration of war on Spain, and Goyaâs illness was developing. A contemporary reported, âthe noises in his head and deafness arenât improving, yet his vision is much better and he is back in control of his balance.â His symptoms may indicate prolonged viral encephalitis or possibly a series of mini-strokes resulting from high blood pressure and affecting hearing and balance centers in the brain.

Caprichos

In 1799 Goya published a series of 80 prints entitled Caprichos, depicting what he described as "the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual."[5]

The dark visions depicted in these prints are partly explained by his caption, "The sleep of reason produces monsters" (alternate translation: "The dreams of reason produce monsters"). Yet these are not solely bleak in nature and demonstrate the artist's sharp satirical wit, particularly evident in etchings such as Hunting for Teeth. Additionally, one can discern a thread of the macabre running through Goya's work, even in his earlier tapestry cartoons.

Black paintings and The disasters

In later life Goya bought a house, called Quinta del Sordo ("Deaf Man's House"), and painted many unusual paintings on canvas and on the walls, including references to witchcraft and war. One of these is the famous work Saturn Devouring His Sons (known informally in some circles as Devoration or Saturn Eats His Child), which displays a Greco-Roman mythological scene of the god Saturn consuming a child, a reference to Spain's ongoing civil conflicts. Moreover, the painting has been seen as "the most essential to our understanding of the human condition in modern times, just as Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling is essential to understanding the tenor of the sixteenth century."[6] This painting is one of 14 in a series called the Black Paintings. After his death the wall paintings were transferred to canvas and remain some of the best examples of the later period of Goya's life when, deafened and driven half-mad by what was probably an encephalitis of some kind, he decided to free himself from painterly strictures of the time and paint whatever nightmarish visions came to him. Many of these works are in the Prado museum in Madrid.

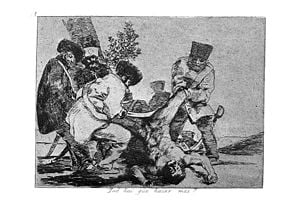

In the 1810s, Goya created a set of aquatint prints titled The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra) which depict scenes from the Peninsular War of 1808â1814. The scenes are singularly disturbing, sometimes macabre in their depiction of battlefield horror, and represent an outraged conscience in the face of death and destruction. The prints were not published until 1863, 35 years after Goya's death.

In The Third of May, 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid, Goya attempted to "perpetuate by the means of his brush the most notable and heroic actions of our glorious insurrection against the Tyrant of Europe."[7] The painting does not show an incident that Goya witnessed; rather it was meant as more abstract commentary.

Legacy

Goya is a pivotal figure in Western art, often described as the last of the old school painters and simultaneously the first of the modern artists, who would influence most of modern art, including Romanticism, French Impressionism and even Pablo Picasso. Given his importance, his life and work has been portrayed in multiple films and even opera.

Film portrayals

- Goya (1948) at the Internet Movie Database

- Goya, historia de una soledad (1971) at the Internet Movie Database

- Goya in Bordeaux (1999) at the Internet Movie Database

- Volavérunt (1999) at the Internet Movie Database

- Goya's Ghosts (2006) at the Internet Movie Database

Operas

Enrique Granados composed a piano suite and later an opera called Goyescas inspired by the artist's paintings in 1916. Gian Carlo Menotti wrote a biographical opera about him titled Goya (1986), commissioned by PlĂĄcido Domingo, who originated the role; this production has been presented on television. He also inspired Michael Nyman's opera Facing Goya (2000), in which he appears in the present to protest the use of his skull in racist science, for which reason the historical Goya had his skull hidden and not buried with the rest of his body. Goya is the central character in Clive Barker's play Colossus.

In 1988 American musical theatre composer Maury Yeston released a studio cast album of his own musical, Goya: A Life In Song. PlĂĄcido Domingo again starred as Goya, with Jennifer Rush, Gloria Estefan, Joseph Cerisano, Dionne Warwick, Richie Havens, and Seiko Matsuda singing supporting roles. Music and lyrics were by Yeston, and the recording was released by CBS/Sony. The score featured one break-out song, âTill I Loved You,â sung by Placido Domingo and Gloria Estefan. It was subsequently a Top 40 hit by Barbra Streisand. In spite of that commercial success, the piece has not received a major staging.

Notes

- â Galeria de Arte transparencias Ancora A Todo Color, (Ediciones Minos, 1961). Goya biography from the Museo del Prado. As quoted on eeweems.com. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- â Fred Licht, Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art (Palgrave Macmillan, 1979), 68.

- â Rosario Weiss. Jose de la Mano Madrid Art Gallery. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- â Licht, 83

- â Linda Simon, The Sleep of Reason The World & I. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

- â Licht, 167.

- â Francisco Goya, quoted by Kenneth Clark, Looking at Pictures. Artchive.com.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Feuchtwanger, Lion. Goya (a biographical novel) Edaf, 2002. ISBN 8441410658 (Spanish version, ISBN 8476408838)

- Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York, NY: Knopf, 2006. ISBN 0375711287

- Licht, Fred. Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 1979. ISBN 0876632940

External links

All links retrieved April 9, 2024.

- Goya's ghouls on the Goya's exhibition in Berlin "Don't forget the happiness of Goya!" by Claudia Schwartz at signandsight.com

- Francisco de Goya's Black paintings

- Desastres de la guerra (PDF in the Arno Schmidt Reference Library)

- Goya Y Lucientes, Francisco de Web Gallery of Art

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

|   Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - SĆowacki - Wordsworth   | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - GĂ©ricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.