The Buddha most commonly refers to SiddhÄrtha Gautama (Sanskrit; Pali: SiddhÄttha Gotama), also called Shakyamuni (âsage of the Shakyas,â in Pali "Åakamuá¹i"), who was a spiritual teacher from ancient India and the historical founder of Buddhism. A majority of twentieth-century historians date his lifetime from 563 B.C.E. to 483 B.C.E.

Etymologically, the term Buddha is the past participle of the Sanskrit root budh, i.e. "to awaken," "to know," or "to become aware"; it literally means "The Awakened One." SiddhÄrtha used the term to describe himself: he was not a king; he was not a god; he was simply "awake" and not asleep. He described himself as a being who has become fully awakened or Bodhi (enlightened), who has permanently overcome anger, greed, and ignorance, and has achieved complete liberation from suffering, better known as Nirvana.

SiddhÄrtha Gautama established the Dharma,[1] or teaching, that leads to Enlightenment, and those who follow the teaching are considered as disciples of SiddhÄrtha. Accounts of his life, his discourses, and the monastic rules he set up, were memorized by the community of his followers (the Sangha) and codified after his death. Passed down by oral tradition at first, within four hundred years they were committed to writing as the Tripitaka, the collection of discourses attributed to the Buddha. The "three refuges" that Buddhists rely on are these: the Buddha (SiddhÄrtha Gautama), the Dharma and the Sangha.

The Buddha taught an arduous path to salvation that requires coming to complete awareness of the self and its myriad self-centered desires, or "cravings," that bind us to suffering and keep us in ignorance. More than any other religious founder, he taught the way to discipline and deny the body, the egoistic self, and any sort of self-seeking, in order to achieve a state of complete selflessness (anatta) or "emptiness." In attaining the state that is absolutely empty, the seeker becomes unified, free of desires, able to live a fully awakened existence. People of many religions have found the meditative disciplines of Buddhism of great help in their walks of faith.

The Buddha taught non-violence, respect for all life, the merit of giving generously and of a simple lifestyle, serving for many people as a model of the highest standards of humane behavior. The historical Buddha's contribution to humanity in terms of ethical conduct, peace, and reverence for life is considered by many to rank among the most positive legacies of any individual. Buddhism spread far and wide, and although sometimes Buddhists have departed from SiddhÄrtha's teaching and waged war, Buddhist-majority states have been characteristically peaceful and less interested in territorial acquisition and imperial expansion than other nations.

While SiddhÄrtha Gautama is universally recognized by Buddhists as the supreme Buddha of our age, Buddhism teaches that anyone can become enlightened (Bodhi) on their own, without a teacher to point out the dharma in a time when the teachings do not exist in the world: such a one is a Buddha (the Pali scriptures recognize 28 such Buddhas). Since in this age the Buddha has revealed the teaching, a person who achieves enlightenment by following that teaching becomes an Arhat or Arahant, not a Buddha.

A new Buddha will arise for the next age, whom many Buddhists believe will be called Maitreya Buddha. His coming will be necessary because as this age nears its end, there will be a decline in fidelity to the dharma and the knowledge leading to enlightenment will gradually disappear.

The Historical Buddha

Sources for his life

The collection of texts of the Buddha's teachings, the Tripitaka (Basket of Three Scriptures), known in English as the Pali Canon, containâalthough not in a chronological or systematic wayâa lot of information about his life. In the second century C.E., several birth to death narratives were written, such as the Buddhacarita (âActs of the Buddhaâ) by Ashvaghosa. In the fourth or fifth centuries C.E., the Mulasarvastivada was compiled.

Accounts of the historical Buddhas' life follow a stylized format and also contain stories of miraculous events, which secular historians think were added by his followers in order to emphasize his status. Miraculous stories surrounding his birth are similar to those associated with other significant religious teachers.

Buddhists believe that before he "awoke," or achieved Enlightenment, Siddhartha had lived 549 previous existences, each time moving a step closer to awakening by performing a virtuous deed. These stories are told in the Jataka, one of the texts of the Pali Canon.

A few scholars have challenged the historicity of SiddhÄrtha, pointing out that only insider (Buddhist) sources are there authenticate his existence. Interestingly, the same is true for Jesus and to a very large extent for Muhammad as well. Others argue that his existence cannot seriously be doubted. Carrithers (1983) concluded that "at least the basic outline of his life must be true."[2] Some argue that even if he is not an historical person, the teachings attributed to him represent an ethic of the highest standard. In addition to the texts available there are also rock inscriptions in India that depict various details of his post-enlightenment story, such as those commissioned by King Ashoka.

Chronology

The time of his birth and death are uncertain. Buddhist accounts record that he was 80 years old when he died. Many scholars date SiddhÄrtha's lifetime from 563 B.C.E. to 483 B.C.E., though some have suggested dates about a century later than this. This chronology is debated and there are some scholars who date his birth about a century later.[3]

Biography

SiddhÄrtha was born in the Himalayan city of Lumbini in modern Nepal. His father, Shuddodana, was the local king, although his clan, the Sakya, prided themselves on a sense of equality. SiddhÄrtha would also become known by the title "Sakyamuni," or "Sage of the Sakyas." Technically Kshatriyas (the second highest class of warriors), they did not regard Brahmins (or Brahmans), the highest (priestly) class, as in any way superior. Perhaps they leaned towards a more democratic type of religion, in which religious obligations could be fulfilled by anyone regardless of their class.

Stories surrounding SiddhÄrtha's birth include his mother, Maya, conceiving him after being touched by a white elephant. At his birth, a tree bent to lend her support and she experienced no birth pains. SiddhÄrtha could walk and talk at birth. When SiddhÄrtha's father presented him to the people, an old sage, Asita, appeared and predicted that he would either conquer the world, or become a great spiritual teacher.

Comparative scholars note that in some of the non-canonical gospels have Jesus talking at birth, as he also does in the Qur'an (3:46). Again, the story of "recognition" by an elderly sage features in that of Jesus (see Luke 1:30) and of Muhammad.

Determined that his son would fulfill the first, not the second prediction, Shuddodana protected him from anything ugly or unhealthy by building for him a series of beautiful palaces which he peopled with young, healthy, handsome women and men. Anyone who ceased to fit this description was removed. The idea was that SiddhÄrtha would be so content that he would not ask such questions as "why do people suffer?" "why do people die?" or "what is the purpose of life?" When the boy reached the age of 16, his father arranged his marriage to YaÅodharÄ (PÄli: YasodharÄ), a cousin of the same age. In time, she gave birth to a son, Rahula.

Yet curiosity about the kingdom he was one day to rule outside the walls of the palace-complex led him to ask Shuddodana if he could visit the city. He was 29. Shuddodana agreed but first tried to sanitize the city by removing the old, the infirm, and the ugly. The palace gates were thrown open, and SiddhÄrtha, driven by a charioteer, emerged to the sight of beautiful people shouting greetings to their prince. However, SiddhÄrtha ended up going off track, and saw what became known as "the four signs."

The Four Signs

The four signs were an old man, a sick man, a dead man, and a Sadhu, or mendicant religious ascetic. Asking his charioteer the meaning of each sign, he was informed that sickness, age, and death are universal and that even he might sicken, but that certainly he would grow old and die. The mendicant, SiddhÄrtha learned, was dedicating his life to find answers to such questions as "what is the point of life if it ends in death?"

The Great Renunciation

There and then, SiddhÄrtha knew that he must renounce his life of ease and privilege to discover what causes such suffering as he had witnessed, and how suffering could be overcome. Some accounts have him seeking his father's permission to leave the palace, most depict him leaving in the dead of night, when a miraculous sleep overcame all the residents and the palace doors opened up to allow his departure.

SiddhÄrtha initially went to Rajagaha and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. Having been recognized by the men of King Bimbisara, Bimbisara offered him the throne after hearing of SiddhÄrtha's quest, but he rejected the offer. Siddhartha left Rajagaha and practiced under two hermit teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta. After mastering the teachings of each one and achieving high levels of meditative consciousness, SiddhÄrtha was still not satisfied, and moved on.

Siddhartha and a group of five companions then set out to take their austerities even further. They tried to find enlightenment through near total deprivation of worldly goods, including food, practicing self-mortification. After nearly starving himself to death by restricting his food intake to around a leaf or nut per day, he collapsed in a river while bathing and almost drowned. SiddhÄrtha began to reconsider his path. Then, he remembered a moment in childhood in which he had been watching his father start the season's plowing, and he had fallen into a naturally concentrated and focused state that was blissful and refreshing. He accepted a little milk and rice pudding from a village girl. Then, sitting under a pipal tree, now known as the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth. His five companions left, believing that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined.

Concentrating on meditation or Anapana-sati (awareness of breathing in and out), SiddhÄrtha embarked on the Middle Wayâa path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. As he continued his meditation, he was accosted by Mara, the devil, who tempted him in various ways prevent his enlightenment, but SiddhÄrtha saw through him. After 49 days meditating, he attained Enlightenment. He had ceased to be trapped in the endless cycle of existences known as samsara; he was liberated. SiddhÄrtha, from then on, was known as âthe Buddhaâ or "Awakened One."

At the age of 35, Siddhartha now had insight into the nature and cause of human suffering, along with steps necessary to eliminate it. Having great compassion for all beings in the universe, he began to teach.

According to one of the stories in the ÄyÄcana Sutta,[4] immediately after his Enlightenment, the Buddha was wondering whether or not he should teach the dharma to human beings. He was concerned that, as human beings were overpowered by greed, hatred and delusion, they would not be able to see the true dharma, which was subtle, deep and hard to understand. However, a divine spirit, thought to have been Brahma the Creator, interceded and asked that he teach the dharma to the world, as "There will be those who will understand the Dharma." He therefore agreed to become a teacher.

Formation of the sangha

After becoming enlightened, the Buddha journeyed to Deer Park near Varanasi (Benares) in northern India. There he delivered his first sermon to the group of five companions with whom he had previously sought enlightenment; thus he "set in motion the Wheel of Dharma." They, together with the Buddha, formed the first sangha (the company of Buddhist monks), and hence, the first formation of Triple Gem (Buddha, dharma and sangha) was completed, with Kaundinya becoming the first arahant (âworthy oneâ).

The Buddha saw himself as a doctor, diagnosing the problem, the dharma as the medicine or prescription and the sangha as the nurse. These are the "three refuges" (ashrama) that denote self-identification as a Buddhist. For those who do not become monks and join the sangha, dana (giving) was, he said, an act of merit as this affirms the value of others and avoids self-centeredness. Dana is especially appropriate for those who do not become full-time mendicants (bhikkus), but remain lay-Buddhists and stay married. Bhikkhus do not perform physical work or cook food, but depend on the generosity of the lay-Buddhists. In return, they teach.

All five soon become arahants, and within a few months the number of arahants swelled to 60. The conversion of the three Kassapa brothers and their two hundred, three hundred and five hundred disciples swelled the sangha over one thousand. These monks were then dispatched to explain the dharma to the populace.

Ministry

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and southern Nepal, teaching his doctrine and discipline to an extremely diverse range of peopleâfrom nobles to outcast street sweepers, even mass murderers and cannibals.

He debated with adherents of rival philosophies and religions. He adapted what he taught to his audience, teaching that people at different stages on the path have different needs. This is called the doctrine of "skillful means." Sometimes what he taught appears contradictory, but the intent was to avoid dogmatism. He encouraged his listeners to ask questions and to test what he taught to see if it worked for them. If not, they should adapt his teaching. "It would be stupid to carry a raft on dry-land once it had transported us across water," he said. Even over-attachment to his teaching can trap one in samsara. He taught guidelines or precepts, not laws or rules. He used many metaphors and lists to summarize the dharma.

The communities of Buddhist monks and nuns (the sangha) he founded were open to all races and classes and had no caste structure. The sangha traveled from place to place in India, expounding the dharma. Wherever it went, his community met with a mixture of acceptance and rejection, the latter including even attempts on the Buddha's life. They traveled throughout the year, except during the four months of the rainy season. During this period, the sangha would retreat to a monastery, public park or a forest and people would come to them.

The first rainy season was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was first formed. Afterwards he travelled to Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha to visit King Bimbisara, in accordance with a promise he made after enlightenment. It was during this visit that Sariputta and Mahamoggallana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples; they were to become the Buddha's two foremost disciples. The Buddha then spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha. The monastery, which was of a moderate distance from the city center, was donated by King Bimbisara.

Upon hearing of the enlightenment, his father King Suddhodana dispatched royal delegations to ask the Buddha to return to Kapilavastu. Nine delegations were sent in all, but each time the delegates joined the sangha and became arahants, and none conveyed the king's message. Finally with the tenth delegation, lead by Kaludayi, a childhood friend, the Buddha agreed and embarked on a two-month journey to Kapilavastu by foot, preaching the dharma along the way. Upon his return, the royal palace had prepared the midday meal, but since no specific invitation had come, the sangha went for an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana hastened to approach the Buddha, stating "Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms," to which the Buddha replied:

That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms.

Suddhodana invited the sangha back to the royal palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk, after which he became a supporter. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. His cousins Ananda and Anuruddha were to become two of his five chief disciples. His son Rahula also joined the sangha at the age of seven, and would become one of the ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined the sangha and became an arahant. Another cousin Devadatta also became a monk, although he later became an enemy and tried to kill the Buddha on multiple occasions.

Of his disciples, Sariputta, Mahamoggallana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha comprised the five chief disciples. His ten foremost disciples were completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana, and Punna.

In the fifth year after his enlightenment, the Buddha was informed of the impending death of Suddhodana. He went to his father and preached the dharma, and Suddhodana became an arahant prior to death. The death and cremation led to the creation of the order of nuns. Buddhist texts record that he was reluctant to ordain women as nuns. His foster mother Maha Pajapati approached him asking to join the sangha, but the Buddha refused, and began the journey from Kapilavastu back to Rajagaha. Maha Pajapati was so intent on renouncing the world that she lead a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, following the sangha to Rajagaha. The Buddha eventually accepted them on the grounds that their capacity for enlightenment was equal to that of men, but he gave them certain additional rules (Vinaya) to follow. His wife Yasodhara also became a nun, with both Maha Pajapati and Yasodhara becoming arahants.

Devadatta

During his ministry, Devadatta (who was not an arahant) frequently tried to undermine the Buddha. At one point Devadatta asked the Buddha to stand aside to let him lead the sangha. The Buddha declined, and stated that Devadatta's actions did not reflect on the Triple Gem, but on him alone. Devadatta conspired with Prince Ajatasattu, son of Bimbisara, so that they would kill and usurp the Buddha and Bimbisara respectively.

Devadatta attempted three times to kill the Buddha. The first attempt involved the hiring of a group of archers, whom upon meeting the Buddha became disciples. A second attempt followed when Devadatta attempted to roll a large boulder down a hill. It hit another rock and splintered, only grazing the Buddha in the foot. A final attempt, by plying an elephant with alcohol and setting it loose, again failed.

After failing to kill him, Devadatta attempted to cause a schism in the sangha, by proposing extra restrictions on the vinaya. When the Buddha declined, Devadatta started a breakaway order, criticizing the Buddha's laxity. At first, he managed to convert some of the bhikkhus, but Sariputta and Mahamoggallana expounded the dharma to them and succeeded in winning them back.

When the Buddha reached the age of 55, he made Ananda his chief attendant.

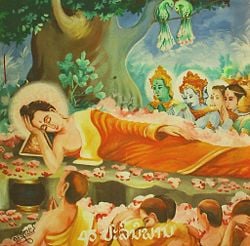

The Great Passing

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon enter Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, abandoning the earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which, according to different translations, was either a mushroom delicacy or soft pork, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ananda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the much-needed energy for the Buddha.

Ananda protested Buddha's decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of KuÅinÄra (PÄli: KusinÄra) of the Mallas. Buddha, however, reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous king. Buddha then asked all the attendant bhikkhus to clarify any doubts or questions they had. They had none. He then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha's final words were, "All composite things pass away. Strive for your own salvation with diligence."

According to the PÄli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dipavamsa and Mahavansa, the coronation of AÅoka (PÄli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of Buddha. According to one Mahayana record in Chinese (åå «é¨è« and é¨å·ç°è«), the coronation of AÅoka is 116 years after the death of Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha's passing is either 486 B.C.E. according to TheravÄda record or 383 B.C.E. according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha's death in TheravÄda countries is 544 or 543 B.C.E., because the reign of AÅoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates.

The Buddha's body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. At his death, the Buddha told his disciples to follow no leader, but to follow his teachings (dharma). However, at the First Buddhist Council, Mahakasyapa was held by the sangha as their leaderâthe two chief disciples Mahamoggallana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

The Buddha's Teachings

In brief, Siddhartha taught that everything in samsara is impermanent, and that as long as people remain attached to a sense of selfâto possessions, to power, to food, to pleasureâthey will also remain trapped in the birth-death-rebirth cycle. Since nothing is permanent (anicca), what lives on from one existence to the next is not a "soul," but a set of experiences. A basic teaching of the Buddha is that there is no soul (anatta).

Buddhism has no need of priests with exclusive privileges; it is democratic. Existence is thus a temporary condition, a mixture of matter, feelings, imagination, will, and consciousness. What one thinks of as "real" is not really real. Reality lies outside samsara, and is experienced when one "wakes up." Nirvana (the state of having woken up), thus, cannot be described. Western scholars have depicted Buddhism as a negative religion that aims at the extinction of the self. For the Buddha, however, to be in nirvana was to know bliss. One can no more describe nirvana than describe what happens when a candle is extinguished, but nirvana is the absence of all desire.

The Buddha's teaching is often summarized as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eight Fold Path:

The Four Noble Truths

- all of life is suffering (dukkha)

- suffering (dukkha) is caused by desire

- suffering can be overcome

- by following the Eight Fold Path

The Noble Eight Fold Path: Right understanding, right resolve (classed as wisdom), right speech, right action, right livelihood (for example, this excludes any life-taking occupation) (classed as ethics), right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation (classed as meditation or contemplation).

Full-time mendicants keep a set of precepts, some of which also apply to laity. In addition, the Buddha gave a detailed "rule" for the sangha, contained in the Vinaya (part of the Pali canon). Reverence for all sentient beings is central to Buddhist ethics.

Some critics point out that the Buddha neglected family and domestic life. This is true to the degree that for him the ideal was to become a Bhikkhu, but he did leave many precepts for lay Buddhists as well, including guidance for ruler followed as a successful socio-political polity by the great Indian king, Ashoka, whose children took Buddhism to Sri Lanka. Ashoka repudiated violence for "conquest by righteousness." Buddhism does not encourage the accumulation of excessive wealth but nor does it demand complete self-denial.

Characteristics of the Buddha

Physical characteristics

Buddha is perhaps one of the few sages for whom we have mention of his rather impressive physical characteristics. He was at least six feet tall. A kshatriya by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a warrior in order to marry. He had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also believed by Buddhists to have "The 32 Signs of the Great Man."

Although the Buddha was not represented in human form until around the first century C.E. (see Buddhist art), his physical characteristics are described by Yasodhara to his son Rahula in one of the central texts of the traditional Pali canon, the Digha Nikaya. They help define the global aspect of the historical Buddha.

Having been born a kshatriya, he was probably of Indo-Aryan ethnic heritage and had the physical characteristics most common to the Aryan warrior castes of south-central Asia, typically found among the Vedic Aryans, Scythians and Persians. This stands in contrast to the depictions of him as East Asian looking, which are generally created by Buddhists in those areas, similar to the way Northern Europeans often portray the Semitic Jesus as blonde and blue-eyed.

Spiritual realizations

All traditions hold that a Buddha has completely purified his mind of greed, aversion, and ignorance, and that he has put an end to samsara. A Buddha is fully awakened and has realized the ultimate truth of life (dharma), and thus ended (for himself) the suffering which unawakened people experience in life. Also, a Buddha is complete in all spiritual powers that a human being can develop, and possesses them in the highest degree possible.

Nine characteristics

Buddhists meditate on (or contemplate) the Buddha as having nine excellent qualities:

The Blessed One is:

- a worthy one

- perfectly self enlightened

- stays in perfect knowledge

- well gone

- unsurpassed knower of the world

- unsurpassed leader of persons to be tamed

- teacher of the Divine Gods and humans

- the Enlightened One

- the Blessed One or fortunate one

These nine characteristics are frequently mentioned in the Pali canon, and are chanted daily in many Buddhist monasteries.

The Nature of Buddha

The various Buddhist schools hold some varying interpretations on the nature of Buddha.

Pali canon: Buddha was human

From the Pali canon emerges the view that Buddha was human, endowed with the greatest psychic powers (Kevatta Sutta). The body and mind (the five khandhas) of a Buddha are impermanent and changing, just like the body and mind of ordinary people. However, a Buddha recognizes the unchanging nature of the Dharma, which is an eternal principle and an unconditioned and timeless phenomenon. This view is common in the Theravada school, and the other early Buddhist schools. However, the Buddha did not deny the existence of Gods, who feature in his biography, only that they can help one escape samsara. They can grant worldly favors, though. Buddhism has thus been characterized as a "self-help" systemâpeople have to "wake up" themselves; no savior-type figure will do this for them.

Eternal Buddha in Mahayana Buddhism

Some schools of Mahayana Buddhism believe that the Buddha is no longer essentially a human being but has become a being of a different order altogether, and that the Buddha, in his ultimate transcendental "body/mind" mode as Dharmakaya, has an eternal and infinite life. In the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha declares: "Nirvana is stated to be eternally abiding. The Tathagata [Buddha] is also thus, eternally abiding, without change." This is a particularly important metaphysical and soteriological doctrine in the Lotus Sutra and the Tathagatagarbha sutras. According to the Tathagatagarbha sutras, failure to recognize the Buddha's eternity andâeven worseâoutright denial of that eternity, is deemed a major obstacle to the attainment of complete awakening (bodhi).

Types of Buddhas

Since Buddhahood is open to all, the Buddhist scriptures distinguish various types or grades of Buddhas.

In the Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, there are considered to be two types of Buddhas: Samyaksambuddha (Pali: Sammasambuddha) and Pratyeka Buddha (Pali: Paccekabuddha).

Samyaksambuddhas attain Buddhahood and decide to teach others the truth that he or she has discovered. They lead others to awakening by teaching the dharma in a time or world where it has been forgotten or has not been taught before. The Historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, is considered a Samyaksambuddha.

Pratyekabuddhas, sometimes called âSilent Buddhas,â are similar to Samyaksambuddhas in that they attain Nirvana and acquire the same powers as a Sammasambuddha does, but they choose not to teach what they have discovered. They are second to the Buddhas in their spiritual development. They do ordain others; their admonition is only in reference to good and proper conduct (abhisamÄcÄrikasikkhÄ).

Some scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism (and one twelfth-century Theravadin commentary) distinguish three types of Buddhas. The third type, called a Shravakabuddha, describes the enlightened disciple.

Shravakabuddhas (Pali: Savakbuddha or Anubuddha) are disciples of a Sammasambuddha, meaning shravakas (hearers or followers) or arahants (noble ones). These terms have slightly varied meanings but can all be used to describe the enlightened disciple. Anubuddha is a rarely used term, but was used by the Buddha in the Khuddakapatha as to those who become Buddhas after being given instruction. Enlightened disciples attain Nirvana just as the two types of Buddhas do. However, the most generally used term for them is âarahant.â

In this case, however, the common definition of the meaning of the word Buddha (as one who discovers the Dhamma without a teacher) does not apply anymore.

Depictions of the Buddha in art

Buddhas are frequently represented in the form of statues and paintings. Commonly seen designs include:

- Seated Buddha

- Reclining Buddha

- Standing Buddha

- Hotei, the obese, laughing Buddha, is usually seen in China. This figure is believed to be a representation of a medieval Chinese monk who is associated with Maitreya, the future Buddha, and it is therefore not technically a Buddha image.

- Emaciated Buddha, which shows SiddhÄrtha Gautama during his extreme ascetic practice of starvation.

Buddha rupas (images) may depict him with the facial features of the country in which the image is made, which represents the Buddha nature (or the inner potential for enlightenment) within all people.

Markings

Most depictions of Buddha contain a certain number of "markings," which are considered the signs of his enlightenment. These signs vary regionally, but two are common:

- A protuberance on the top of the head (denoting superb mental acuity)

- Long earlobes (denoting superb perception, and the fact that he may have worn heavy earrings)

In the Pali canon there is frequent mention of a list of 32 physical marks of Buddha.

Hand-gestures

The poses and hand-gestures of these statues, known respectively as asanas and mudras, are significant to their overall meaning. The popularity of any particular mudra or asana tends to be region-specific, such as the Vajra (or Chi Ken-in) mudra, which is popular in Japan and Korea but rarely seen in India. Others are more universally common, for example, the Varada (wish granting) mudra is common among standing statues of the Buddha, particularly when coupled with the Abhaya (fearlessness and protection) mudra.

Relics

After his death, relics of the Buddha (such as his staff, his teach, hair, bones, and even a footprint) were distributed throughout India and elsewhere among the Buddhist community, and stupas were built to house them. Stupas represent the Buddha's awakened mind and the path to enlightenment that he trod. While the Buddha is no longer within samsara, Stupas remind people that enlightenment is within everyone's grasp.

The Buddha and other religions

The Buddha thought that different religions may suit different people at differing times on their journey. However, since for the Buddha the path to salvation lies within oneself, those religions that teach that an external savior can ultimately save people may hinder progress. For this reason, the Buddha preferred not to speak of belief in a Supreme Being. For this reason, some people criticize his teaching as atheistic.

However, the Buddha's "atheism" should be seen in the context of the Hinduism of his day, with its many deities and elaborate mythology. The Hindu gods were commonly portrayed anthropomorphically, possessed of desires, loves and hates; hence despite their glory they were inferior to a person who attains a set of complete "quenching" which is Nirvana. The Buddha did not have occasion to encounter any monotheistic religion during his lifetime. God in the Western monotheistic faiths is often conceived of as beyond any anthropomorphic description.

Many Christians admire the Buddha, and regard him second only to Jesus. Despite SiddhÄrtha's practical atheism, some Christians nevertheless see the hand of God guiding his life from behind, for example in the voice of Brahma who persuaded him to spread his teachings to others (see above).

Doctrinally, Christians may be critical of SiddhÄrtha's self-help system, believing that humanity is too sinful to redeem themselves, but as to practice, they often admire SiddhÄrtha's teaching, his ethic, and his non-violence. Some scholars have investigated parallels between the sayings of Jesus and of the Buddha, while several have argued that Jesus visited India and studied Buddhism, or that Buddhist influences impacted on the gospels. Buddhists have also written sympathetically about Jesus, commenting on the similarity of SiddhÄrtha's and Jesus' teaching.

In Hinduism, the Buddha is often listed as one of the manifestations (avataras) of Vishnu, such as Ram and Krishna. From a Buddhist perspective, this inclusion of SiddhÄrtha as a Hindu deity is problematic for several reasons; first, SiddhÄrtha says that he was not a god. Second, he rejected the basic Hindu concept of the atman as that within all beings that is a spark of Brahman (ultimate reality), since his system does not posit any such reality. Also, while in Vaishnavism, it is devotion to Vishnu (or to one of his manifestations) that will result in release from samsara, thus, one is "saved." SiddhÄrtha taught that no external agent can assist enlightenment. SiddhÄrtha may have been reacting both to Brahmanism, which left everything to the priests, and to the bhakti (devotional) tradition, that leaves liberation to the gods (albeit in return for devotion and a righteous life).

Legacy

The Buddha remains one of the most respected religious teachers, whose philosophy of non-violence and practice of cultivating selflessness are increasingly seen to have been precociously insightful in a world self-seeking people and groups often fall into violent disputes. Buddhism is the third largest religion. The Buddha's teaching has been and continues to be the main source of guidance for millions of people, whose goal is to be less self-centered, more compassionate, considerate, and kinder towards others.

Gautama Buddha taught respect for all sentient life. The early twenty-first century is waking up to the fact that earth is the planetary home of other species than the human. In this, as in his non-violent ethic, the Buddha anticipated concerns for the welfare of the whole planet.

Notes

- â English spelling follows either a transliteration of the original Pali language spoken by Siddhartha and in which the scriptures were written, or of the Sanksrit used by many Buddhists from a later period. For example, the Pali is nibbhana, the Sanskrit nirvana, the Pali is Siddhattha, the Sanskrit Sidhhartha, the Pali is dhamma, the Sanskrit is dharma.

- â Michael Carrithers, The Buddha (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983, ISBN 0192875906), 3.

- â Lance S. Cousins, "The Dating of the Historical Buddha: A Review Article" Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Series 3, 6.1 (1996): 57-63. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- â Samyutta Nikaya VI.1 of the PÄli Canon.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carrithers, Michael. The Buddha: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0192854534

- Conze, Edward. Buddhist Scriptures. New York: Penguin, 1959. ISBN 0140440887

- RÄhula, Walpola. What the Buddha Taught. New York: Grove Press, 1974. ISBN 0802100562

- Swe, Khin Myint Myint. Buddha - The Compassionate Teacher. Seattle, WA: May-Su-Thin-Mu and Brothers Maw, 2002.

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2023.

- BuddhaNetâs Buddhist Studies â Buddha Dharma Education Association

- About Buddha

- The Life of the Buddha â Vipassana Research Institute

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.