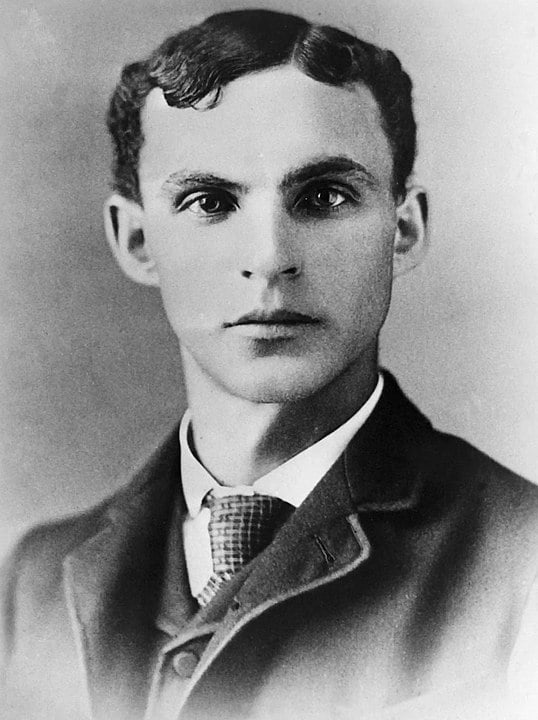

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1864 – April 7, 1947) was the founder of the Ford Motor Company and the father of the modern assembly lines used in mass production. His “Model T” eventually revolutionized transportation and American industry, contributing to the urbanization that changed American society in the early twentieth century. He became famous for introducing higher wages for his workers—notably $5.00 a day—which brought thousands of workers to his factories and made the automobile industry one of the largest in the nation. His intense commitment to lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that put a dealership in every city in North America, and in major cities on six continents.

Ford's impact on the American life was immense. By paying his workers above subsistence wages, and producing cars that were priced for this new market of workers as consumers, Ford brought the means of personal transportation to ordinary people and changed the structure of society. His plan of producing a large number of inexpensive cars contributed to the transformation of major sectors of the United States from a rural, agricultural society to an urbanized, industrial one at a time when America's role in the world appeared to many to have providential significance. A complex personality, often referred to as a genius, Ford exhibited various prejudices and, despite his own numerous inventions and innovations, a stubborn resistance to change. His legacy, however, includes the Ford Foundation, one of the richest charitable foundations in the world, dedicated to support for activities worldwide that promise significant contributions to world peace through strengthening democratic values, reducing poverty and injustice, promoting international cooperation, and advancing human achievement.

Early life

Henry Ford was born on July 30, 1863, on a farm in a rural township west of Detroit, the area which is now part of Dearborn, Michigan. His parents were William Ford (1826–1905) and Mary Litogot (1839–1876). They were of distant English descent but had lived in County Cork, Ireland. His siblings include Margaret Ford (1867–1868), Jane Ford (1868–1945), William Ford (1871–1917), and Robert Ford (1873–1934).

During the summer of 1873, Henry saw his first self-propelled road machine, a steam engine generally used in the stationary mode to power a threshing machine or a sawmill, but also modified by its operator, Fred Reden, to be mounted on wheels connected with a drive chain connected to the steam engine. Henry was fascinated with the machine, and over the next year Reden taught him how to fire and operate it. Ford later said it was this experience "that showed me that I was by instinct an engineer."[1]

Henry took this passion for mechanics into his home. His father had given him a pocket watch in his early teens. At fifteen, he had developed a reputation as a watch repairman, having dismantled and reassembled timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of times.[2]

The death of his mother in 1876 was a blow that devastated little Henry. His father expected Henry to eventually take over the family farm, but Henry despised farm work. With his mother dead, Ford had little reason to remain on the farm. He later said, "I never had any particular love for the farm. It was the mother on the farm I loved."[3]

In 1879, he left home for the nearby city of Detroit, Michigan to work as an apprentice machinist, first with James F. Flower & Brothers, and later with the Detroit Dry Dock Company. In 1882, he returned to Dearborn to work on the family farm and became adept at operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine. This led to his being hired by Westinghouse Electric Company to service their steam engines.

Upon his marriage to Clara Bryant in 1888, Ford supported himself by farming and running a sawmill. They had a single child: Edsel Bryant Ford (1893–1943). In 1894, Ford became a Freemason, joining the Palestine Lodge #357 in Detroit. [4]

In 1891, Ford became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company, and after his promotion to chief engineer in 1893, he had enough time and money to devote attention to his personal experiments on gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of his own self-propelled vehicle named the “Quadricycle,” which he test-drove on June 4 of that year.

Detroit Automobile Company and the Henry Ford Company

After this initial success, Ford approached Edison Illuminating in 1899 with other investors, and they formed the Detroit Automobile Company, later called the Henry Ford Company. The company soon went bankrupt because Ford continued to improve the design, instead of selling cars. He raced his car against those of other manufacturers to show the superiority of his designs.

During this period, he personally drove one of his cars to victory in a race against the famous automobile manufacturer Alexander Winton (1860–1932) on October 10, 1901. In 1902, Ford continued to work on his race car to the dismay of the investors. They wanted a high-end production model and brought in Henry M. Leland (1843–1932) to create a passenger car that could be put on the market. Ford resigned over this usurpation of his authority. He said later that "I resigned, determined never again to put myself under orders."[5] The company was later reorganized as the Cadillac Motor Car Company.

Ford Motor Company

Ford, with eleven other investors and $28,000 in capital, incorporated the Ford Motor Company in 1903. In a newly-designed car, Ford drove an exhibition in which the car covered the distance of a mile on the ice of Lake St. Clair in 39.4 seconds, which was a new land speed record. Convinced by this success, the famous race driver Barney Oldfield (1878–1946), who named this new Ford model "999" in honor of a racing locomotive of the day, took the car around the country and thereby made the Ford brand known throughout the United States. Ford was also one of the early backers of the Indianapolis 500 race.

Self-sufficiency

Ford's philosophy was one of self-sufficiency using vertical integration. Ford's River Rouge Plant, which opened in 1927, became the world's largest industrial complex able to produce even its own steel. Ford's goal was to produce a vehicle from scratch without reliance on outside suppliers. He built a huge factory that shipped in raw materials from mines owned by Ford, transported by freighters and a railroad owned by Ford, and shipped out finished automobiles. In this way, production was able to proceed without delays from suppliers or the expense of stockpiling.

Ford's labor philosophy

Henry Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism" designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the heavy turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men a year to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers. On January 5, 1914, Ford astonished the world by announced his $5 a day program. The revolutionary program called for a reduction in the length of the workday from 9 to 8 hours, a five-day work week, and a raise in minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for qualified workers.[6] The wage was offered to men over age 22, who had worked at the company for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted their lives in a manner of which Ford's "Sociological Department" approved. They frowned on heavy drinking and gambling. The Sociological Department used 150 investigators and support staff to maintain employee standards; a large percentage of workers were able to qualify for the program.

Ford was criticized by Wall Street for starting this program. The move however proved hugely profitable. Instead of constant turnover of employees, the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing in their human capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training costs. Ford called it "wage motive." Also, paying people more enabled the workers to be able to afford the cars they were producing, and was therefore good for the economy.

Ford was adamantly against labor unions in his plants. To forestall union activity, he promoted Harry Bennett, a former Navy boxer, to be the head of the service department. Bennett employed various intimidation tactics to squash union organizing. The most famous incident, in 1937, was a bloody brawl between company security men and organizers that became known as "The Battle of the Overpass."

Ford was the last Detroit automaker to recognize the United Auto Workers union (UAW). A sit-down strike by the UAW union in April 1941 closed the River Rouge Plant. Under pressure from Edsel and his wife, Clara, Henry Ford finally agreed to collective bargaining at Ford plants and the first contract with the UAW was signed in June 1941.

The Model T

The Model T was introduced on October 1, 1908. It had many important innovations—such as the steering wheel on the left, which every other company soon copied. The entire engine and transmission were enclosed; the four cylinders were cast in a solid block; the suspension used two semi-elliptic springs. The car was very simple to drive, and more important, easy and cheap to repair. It was so cheap at $825 in 1908 (the price fell every year) that by the 1920s a majority of American drivers learned to drive on the Model T, leaving fond memories for millions. Ford created a massive publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and advertisements about the new product.

Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in virtually every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford, but the very concept of “automobiling.” Local motor clubs sprang up to help new drivers and to explore the countryside. Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked on the vehicle as a commercial device to help their business. Sales skyrocketed—several years posted 100+ percent gains on the previous year. Always on the hunt for more efficiency and lower costs, in 1913 Ford introduced moving assembly belts to his assembly line, which enabled an enormous increase in production. Sales passed 250,000 units in 1914. By 1916, as the price dropped to $360 for the basic touring car, sales reached 472,000.[7]

By 1918, half of all cars in America were Model T's. Until the development of the assembly line which mandated black because of its quicker drying time, Model Ts were available in several colors. As Ford wrote in his autobiography, "Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black."[8] The design was fervently promoted and defended by Henry Ford, and production continued as late as 1927; the final total production was 15,007,034. This was a record which stood for the next 45 years.

In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson personally asked Ford to run for the Senate from Michigan as a Democrat. Although the nation was at war, Ford ran as a peace candidate and a strong supporter of the proposed League of Nations.[9] In December 1918, Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over to his son Edsel Ford. Henry, however, retained final decision authority and sometimes reversed his son. Henry and Edsel purchased all remaining stock from other investors, thus giving the family sole ownership of the company.

By the mid-1920s, sales of the Model T began to decline due to rising competition. Other automakers offered payment plans through which consumers could buy their cars, which usually included more modern mechanical features and styling not available with the Model T. Despite urgings from Edsel, Henry steadfastly refused to incorporate new features into the Model T, or to form a customer credit plan.

Racing

Ford began his career as a race car driver and maintained his interest in the sport from 1901 to 1913. Ford entered stripped-down Model Ts in races, finishing first (although later disqualified) in an "ocean-to-ocean" (across the United States) race in 1909, and setting a one-mile oval speed record at Detroit Fairgrounds in 1911 with driver Frank Kulick. In 1913, Ford attempted to enter a reworked Model T in the Indianapolis 500, but was told rules required the addition of another 1,000 pounds (450 kg) to the car before it could qualify. Ford dropped out of the race, and soon thereafter dropped out of racing permanently, citing dissatisfaction with the sport's rules and the demands on his time by the now-booming production of the Model Ts.

The Model A

By 1926, flagging sales of the Model T finally convinced Henry to make a new model car. Henry pursued the project with a great deal of technical expertise in design of the engine, chassis, and other mechanical necessities, while leaving the body design to his son. Edsel also managed to prevail over his father's initial objections in the inclusion of a sliding-shift transmission. The result was the successful Ford Model A, introduced in December 1927 and produced through 1931, with a total output of over four million automobiles. Subsequently, the company adopted an annual model change system similar to that in use by automakers today. Not until the 1930s did Ford overcome his objection to finance companies, and the Ford-owned Universal Credit Company became a major car financing operation.

Death of Edsel Ford

In May 1943, Edsel Ford died, leaving a vacancy in the company presidency. Henry Ford advocated long-time associate Harry Bennett (1892–1979) to take the spot. Edsel's widow Eleanor, who had inherited Edsel's voting stock, wanted her son Henry Ford II to take over the position. The issue was settled for a period when Henry himself, at age 79, took over the presidency personally. Henry Ford II was released from the Navy and became an executive vice president, while Harry Bennett had a seat on the board and was responsible for personnel, labor relations, and public relations.

Ford Airplane Company

Ford, like other automobile manufacturers, entered the aviation business during World War I, building Liberty engines. After the war, Ford Motor Company returned to auto manufacturing until 1925, when Henry Ford acquired the Stout Metal Airplane Company.

Ford's most successful aircraft was the Ford 4AT Trimotor—called the “Tin Goose” because of its corrugated metal construction. It used a new alloy called Alclad that combined the corrosion resistance of aluminum with the strength of duralumin. The plane was similar to Fokker's V.VII-3m, and some say that Ford's engineers surreptitiously measured the Fokker plane and then copied it. The Trimotor first flew on June 11, 1926, and was the first successful U.S. passenger airliner, accommodating about 12 passengers in a rather uncomfortable fashion. Several variants were also used by the U.S. Army. About 200 Trimotors were built before it was discontinued in 1933, when the Ford Airplane Division shut down because of poor sales due to the Great Depression.

Peace ship

In 1915, Ford funded a trip to Europe, where World War I was raging, for himself and about 170 other prominent peace leaders. He talked to President Wilson about the trip but had no government support. His group went to neutral Sweden and the Netherlands to meet with peace activists there. Ford said that he believed that the sinking of the RMS Lusitania was planned by the financiers of war to get America to enter the war.

Ford’s effort however came under criticism and ridicule, and he left the ship as soon as it reached Sweden. The whole project resulted in failure.

Anti-Semitism and The Dearborn Independent

In 1918, Ford's closest aide and private secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, purchased an obscure weekly newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, so that Ford could spread his views. By 1920, the newspaper grew virulently anti-Semitic [10] It published "Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion," which was eventually discredited as a forgery. In February 1921, the New York World published an interview with Ford, in which he said "The only statement I care to make about the Protocols is that they fit in with what is going on."[11]

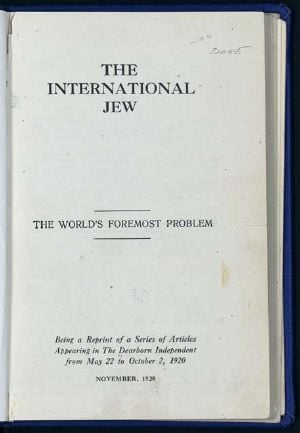

In the early 1920s, The Dearborn Independent published The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem. The book became widely distributed and had great influence, including on Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler, fascinated with automobiles, hung Ford's picture on the wall and planned to model the Volkswagen on the Model T.[12]

A lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer Aaron Sapiro in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to close the Independent in December 1927. Before leaving his presidency early in 1921, Woodrow Wilson joined other leading Americans in a statement that rebuked Ford and others for their anti-Semitic campaign. A boycott against Ford products by Jews and liberal Christians also had an impact on Ford’s decision to shut down the paper. News reports at the time quoted Ford as being shocked by the content of the paper and having been unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval.[13]

Ford’s international business

Ford believed in the global expansion of his company. He imagined that international trade and cooperation would lead to international peace, and used the assembly line process and production of the Model T to demonstrate it.[14]

He opened assembly plants in Britain and Canada in 1911, and Ford soon became the largest automotive producer in those countries. In 1912, Ford cooperated with Fiat to launch the first Italian automotive assembly plants. The first plants in Germany were built in the 1920s with the encouragement of Herbert Hoover, who agreed with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to world peace.[15] In the 1920s Ford also opened plants in Australia, India, and France, and by 1929 he had successful dealerships on six continents.

Ford experimented with a commercial rubber plantation in the Amazon jungle called Fordlândia; it became one of his few failures. In 1929, Ford accepted Stalin's invitation to build a model plant (NNAZ, today GAZ) at Gorky, a city later renamed to Nizhny Novgorod. In any nation having diplomatic relations with the United States, Ford Motor Company worked to conduct business. By 1932, Ford was manufacturing one-third of all the world’s automobiles.

Ford also invested in the business of manufacturing plastic developed from agricultural products, especially soybeans. Soybean-based plastic was used in Ford automobiles throughout the 1930s.

Death

Ford suffered an initial stroke in 1938, after which he turned over the running of his company to Edsel. Edsel's 1943 death brought Henry Ford out of retirement. He eventually turned the business to his grandson, and died in 1947 of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 83 in Fair Lane, his Dearborn estate. He is buried in the Ford Cemetery in Detroit.

Legacy

Henry Ford left a significant legacy after his death. He was a prolific inventor and was awarded 161 U.S. patents. As sole owner of the Ford Company he became one of the richest and best-known people in the world. His introduction of the “Model T” automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry. The Model T forever changed American life—allowing ordinary people access to transportation previously available only to the rich. Within a remarkably short time, the automobile replaced the horse-drawn carriage, causing changes in agriculture, urbanization patterns, and transportation system priorities (displacing mass transit rail networks with privately owned cars operating on an extensive roadway system).

He is credited with "Fordism," that is, the mass production of large numbers of inexpensive automobiles using the assembly line, coupled with high wages for his workers—notably the $5.00 a day pay scale adopted in 1914. Ford, though poorly educated, had a global vision, with consumerism as the key to peace. His intense commitment to lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that put a dealership in every city in North America, and in major cities on six continents. Ford left most of his vast wealth to the Ford Foundation, a charitable foundation based in New York City, created to fund programs that promote democracy, reduce poverty, promote international understanding, and advance human achievement.

Ford's image transfixed Europeans, especially the Germans, arousing the "fear of some, the infatuation of others, and the fascination among all." [16] Those who discussed "Fordism" often believed that it represented something quintessentially American. They saw the size, tempo, standardization, and philosophy of production demonstrated at the Ford Works as a national service—an "American thing" that represented the culture of the United States. Both supporters and critics insisted that Fordism epitomized American capitalist development, and that the auto industry was the key to understanding economic and social relations in the United States. As one German explained, "Automobiles have so completely changed the Americans' mode of life that today one can hardly imagine being without a car. It is difficult to remember what life was like before Mr. Ford began preaching his doctrine of salvation."[17] For many Henry Ford himself embodied the essence of successful Americanism.

Ford later realized the value of the older ways of life and sought to preserve them through the establishment of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. Located in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn, Michigan, it is "the nation's largest indoor-outdoor history museum" complex.[18] More than a museum, it is an entertainment complex where patrons can take a ride in a Model T, ride a train, visit an IMAX Theater, or see a live show. Named for its founder, and based on his desire to preserve items of historical significance and portray the Industrial Revolution, the property houses a vast array of famous homes, machinery, exhibits, and Americana. Henry Ford said of his museum:

I am collecting the history of our people as written into things their hands made and used…. When we are through, we shall have reproduced American life as lived, and that, I think, is the best way of preserving at least a part of our history and tradition.

Notes

- ↑ Ford, My Life and Work, 22; Nevins and Hill, Ford: The Times, the Man, the Company (TMC), 54–55.

- ↑ Ford, My Life and Work, 22–24; Nevins and Hill, Ford TMC, 58.

- ↑ Ford, My Life and Work, 24; Guest, “Henry Ford Talks About His Mother,” 11–15.

- ↑ Ford the Freemason. Grand Master’s Lodge. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ford, My Life and Work, 36.

- ↑ Crowther, “Henry Ford: Why I Favor Five Days' Work With Six Days' Pay,” 614.

- ↑ Lewis, The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company, 41–59.

- ↑ Ford, My Life and Work.

- ↑ Watts, The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, 243–48.

- ↑ Slater and Slater, Great Moments in Jewish History, 190.

- ↑ Glock and Quinley, Anti-Semitism in America, 168.

- ↑ Watts, The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, xi.

- ↑ Lewis, The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company, 140–56; Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate, 220–21.

- ↑ Watts, The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, 236–40.

- ↑ Wilkins, American Business Abroad: Ford on Six Continents.

- ↑ Nolan, Visions of Modernity: American Business and the Modernization of Germany,

- ↑ Nolan, Visions of Modernity: American Business and the Modernization of Germany,

- ↑ Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village: A Local Legacy. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

Selected works

- Ford, Henry. [1921] 2004. The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem. Liberty Bell Publications. ISBN 1593640188

- Ford, Henry, and Samuel Crowther. [1922] 2006. My Life and Work. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 1426422563

- Ford, Henry. [1926] 1988. Today and Tomorrow. Productivity Press. ISBN 0915299364

- Ford, Henry. [1926] 2006. The Great To-Day and Greater Future. Cosimo Classics. ISBN 159605638X

- Ford, Henry. [1930] 2003. My Friend Mr. Edison. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 076614447X

- Ford, Henry, and Samuel Crowther. [1930] 2003. Moving Forward. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0766143392

- Ford, Henry, and Samuel Crowther. 2005. The Fear of Overproduction. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1425454542

- Ford, Henry, and Samuel Crowther. 2005. Flexible Mass Production. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1425454658

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bak, Richard. 2003. Henry and Edsel: The Creation of the Ford Empire. Wiley. ISBN 0471234877

- Baldwin, Neil. 2000. Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate. Public Affairs. ISBN 1586481630

- Bennett, Harry. 1987. Ford: We Never Called Him Henry. Tor Books. ISBN 0812594029

- Brinkley, Douglas G. 2003. Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress. Viking Adult. ISBN 067003181X

- Crowther, Samuel. 1926. Henry Ford: Why I Favor Five Days' Work With Six Days' Pay. World's Work, October, 613–16. Retrieved on March 22, 2007.

- Glock, Charles Y., and Harold E. Quinley. 1983. Anti-Semitism in America. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 087855940X.

- Guest, Edward A. 1923. “Henry Ford Talks about His Mother.” American Magazine, July, 11–15, 116–20.

- Halberstam, David. 1986. “Citizen Ford.” American Heritage 37(6): 49–64.

- Jardim, Anne. 1974. The First Henry Ford: A Study in Personality and Business Leadership. MIT Press. ISBN 0262600056

- Lacey, Robert. 1988. Ford: The Men and the Machine. Random House. ISBN 0517635046

- Lewis, David I. 1976. The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Wayne State U Press. ISBN 0814315534

- Nevins, Allan, and Frank E. Hill. 1954. Ford: The Times, The Man, The Company. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons.

- Nevins, Allan, and Frank E. Hill. 1957. Ford: Expansion and Challenge, 1915–1933. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons.

- Nevins, Allan, and Frank E. Hill. 1962. Ford: Decline and Rebirth, 1933–1962. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons.

- Nolan, Mary. 2001. Visions of Modernity: American Business and the Modernization of Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195070216

- Nye, David E. 1979. Henry Ford: Ignorant Idealist. Associated Faculty Press. ISBN 0804692424

- Preston, James M. 2004. Jehovah's Witnesses and the Third Reich. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802086780.

- Slater, Elinor, and Robert Slater. 1999. Great Moments in Jewish History. Jonathan David Company. ISBN 0824604083.

- Sorensen, Charles E., and Samuel T. Williamson. 2006. My Forty Years with Ford. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 081433279X

- Watts, Steven. 2006. The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century. Vintage. ISBN 0375707255

- Wilkins, Mira, and Frank E. Hill. 1964. American Business Abroad: Ford on Six Continents. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814312276

Further reading

- Batchelor, Ray. 1995. Henry Ford: Mass Production, Modernism and Design. Manchester U. Press. ISBN 0719041740

- Brinkley, Douglas. 2003. “Prime Mover.” American Heritage 54(3): 44–53.

- Bryan, Ford R. 1993. Henry's Lieutenants. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814324282

- Bryan, Ford R. 1997. Beyond the Model T: The Other Ventures of Henry Ford. Wayne State Press. ISBN 081432682X

- Dempsey, Mary A. 1994. “Fordlandia.” Michigan History 78(4): 24–33.

- Kraft, Barbara S. 1978. The Peace Ship: Henry Ford's Pacifist Adventure in the First World War. Macmillan. ISBN 0025665707

- Lee, Albert. 1980. Henry Ford and the Jews. Stein and Day. ISBN 0812827015

- Levinson, William A. 2002. Henry Ford's Lean Vision: Enduring Principles from the First Ford Motor Plant. Productivity Press. ISBN 1563272601

- Lewis, David L. 1984. “Henry Ford's Anti-Semitism and its Repercussions.” Michigan Jewish History 24(1): 3–10.

- Lewis, David L. 1995. “Henry Ford and His Magic Beanstalk.” Michigan Jewish History 79(3): 10–17.

- Lewis, David L. 1993. “Working Side by Side.” Michigan Jewish History 77(1): 24–30.

- McIntyre, Stephen L. 2000. “The Failure of Fordism: Reform of the Automobile Repair Industry, 1913–1940.” Technology and Culture 41(2): 269–299.

- Meyer, Stephen. 1981. The Five Dollar Day: Labor Management and Social Control in the Ford Motor Company, 1908–1921. SUNY Press. ISBN 0873955099

- Raff, Daniel M. G., and Lawrence H. Summers. 1987. “Did Henry Ford Pay Efficiency Wages?” Journal of Labor Economics 5(4): S57–S86.

- Reich, Simon. 1999. The Ford Motor Company and the Third Reich. Dimensions 13(2): 15–17. Retrieved on March 22, 2007.

- Silverstein, K. 2000. “Ford and the Fuhrer.” The Nation 270(3): 11–16

- Thomas, Robert P. 1969. “The Automobile Industry and its Tycoon.” Explorations in Entrepreneurial History 6(2): 139–57.

- Valdés, Dennis N. 1981. “Perspiring Capitalists: Latinos and the Henry Ford Service School, 1918-1928.” Aztlán 12(2): 227–39.

- Wallace, Max. 2004. The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312335318

- Williams, K., C. Haslam, and J. Williams. 1992. “Ford versus 'Fordism': The Beginning of Mass Production?” Work, Employment & Society 6(4): 517–55.

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Ford Foundation – Ford Foundation website.

- The Henry Ford – The Henry Ford Museum website.

- Ford and GM Scrutinized for Alleged Nazi Collaboration – Washington Post article on Ford and General Motors possible collaboration with Nazis.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.