| Schools |

|---|

| Education |

| History of education |

| Pedagogy |

| Teaching |

| Homeschooling |

| Preschool education |

| Child care center |

| Kindergarten |

| Primary education |

| Elementary school |

| Secondary education |

| Middle school |

| Comprehensive school |

| Grammar school |

| Gymnasium |

| High school |

| Preparatory school |

| Public school |

| Tertiary education |

| College |

| Community college |

| Liberal arts college |

| University |

Home education, also called homeschooling or home school, is the process by which children are educated at home rather than at an institution such as a public or private school. Prior to the introduction of compulsory school attendance in the nineteenth century, most education worldwide occurred within the family and community, with only a small proportion of the population attending schools or employing tutors. Homeschooling in the modern sense, however, is an alternative to government operated or private schools, an option that is legal in many countries.

Especially in the English-speaking nations, homeschooling provides an option for parents who wish to provide their children with a quality of education they believe is unattainable in their local schools. Although homeschooling parents worldwide have different educational backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs, for the most part, they possess the parental concern and desire for their children to develop to their full potential and hope to create a nurturing, educational environment at home.

History of homeschooling

The earliest compulsory schooling in the West began in the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century in the German states of Gotha, Heidelheim, Calemberg and, particularly, Prussia. In the United States, the first state to issue a compulsory education law was Massachusetts, in 1789, but not until 1852 did the state establish a true comprehensive statewide, modern system of compulsory schooling."[1] During this time period it was usual for parents in most of the U.S. to utilize books dedicated to home education such as Goodrich's Fireside Education (1838), or Burton's Helps to Education In The Homes Of Our Countries (1863), or to utilize the services of itinerant teachers, as means and opportunity allowed.

After the establishment of the Massachusetts system, other states and localities began to make school attendance mandatory, and the public school system was developed in the U.S. As early as 1912, however, A.A. Berle of Tufts University asserted that the previous 20 years of mass education had been a failure and that he had been asked by hundreds of parents about how they could teach their children at home.[2] In the early 1970s, the premises and efficacy of compulsory schooling came into question with the publication of books like Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich (1970) and No More Public School by Harold Bennet (1972). These ideas developed in the mind of education reformer John Holt to produce, in 1976, Instead of Education: Ways To Help People Do Things Better. After the book's publication, Holt was contacted by families from various parts of the country to tell him that they had taken the almost unheard of step of educating their own children at home, and from this point Holt began producing a magazine dedicated to homeschooling, Growing Without Schooling.

Almost simultaneously, in the mid to late 1970s, educators Ray and Dorothy Moore began to document and publish the results of their research into optimizing educational results in children. The principle finding was that children should not be introduced to formal education until at least 10 years of age for the best social and educational results. The Moores also embraced homeschooling, and became important homeschool advocates with the publication of books like Better Late Than Early (1975) and Home Grown Kids (1984).

The 1990s were a time of both internal and external growth of the homeschooling movement. As the number of homeschoolers multiplied so did its strength and support. Educational materials created for the homeschooling market were produced, online networking developed, organizations started, and homeschooling curriculum sales sprung up offering packaged programs in a variety of learning styles. Hamilton College sociologist, Mitchell Stevens, remarked in his book, Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement:

Home-schooling has become an elaborate social movement, with its own celebrities, rituals and networks, which now encompasses more than a million American children.[3]

Along with the growth in numbers of homeschoolers came successful homeschool graduates, high scoring homeschooler test takers, homeschool winners of awards, and colleges not only accepting homeschoolers but appreciating the study standards of homeschoolers. Gallup polls of American voters have shown a significant change in attitude from 73 percent opposed to home education in 1985 to 54 percent opposed in 2001.[4]

Studies by the Home School Legal Defense Association, a home education advocacy group in the United States, disputed the claim that the academic quality of home education programs is substandard.[5]

While the phenomenon of homeschooling became accepted and promoted, so did the confrontations of opposing views inside the homeschool networks. One debate was whether the American homeschoolers should gain the support of the government and if the movement should lobby for or against bills. Many homeschoolers feared that American government intervention might structure the options for learning and dominate the freedoms homeschoolers wanted to preserve. On the other hand, other American homeschoolers appreciated government support and felt they could help bring about educational reform. The homeschooling movement also experienced the growing pains of accepting other homeschool families’ beliefs and ideas.

Motivations to homeschool

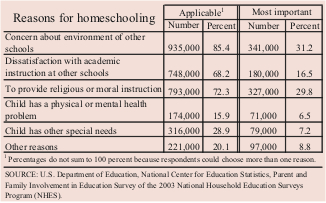

According to a 2003 report, the parents of 33 percent of homeschooled children cited religion as a factor in their choice. The same study found that 30 percent felt that regular school had a poor learning environment, 14 percent objected to what the school teaches, 11 percent felt their children were not being challenged at school, and 9 percent cited morality.[6]

According to a report by the U.S. Department of Education (DOE), 85 percent of homeschooling parents cited "the social environments of other forms of schooling" (including safety, drugs, bullying, and negative peer-pressure) as an important reason why they homeschooled their children. 72 percent cited their "desire to provide religious or moral instruction" as an important reason, and 68 percent cited "dissatisfaction with academic instruction at other schools." Seven percent of parents cited "Child has physical or mental health problem" as anine9 percent cited "Other reasons" (including "child's choice," "allows parents more control of learning" and "flexibility").[7]

Other reasons included the allowance of more flexibility in adapting educational practices for children with learning disabilities or illnesses, or for children of missionaries, military people, or otherwise traveling parents. Homeschooling also is sometimes opted for when a child has a significant career hobby, such as acting, circus performance, dance, or violin. Some prefer to homeschool in order to accelerate study toward early entrance into middle school, high school, or college.

Socialization

Some families feel that the negative social pressures of schools, such as sexualization, bullying, drugs, school violence, and other school-related problems, are detrimental to a child's development. Some such advocates believe that the family unit, not same-age peers, should be the primary vehicle for socialization.

Many homeschoolers participate in a variety of community athletics and membership organizations. Technological advances allow students to relate to other students online on parent approved forums, classes, and other networks based on their interests, cultural backgrounds, and curricula.

Parents or guardians in the homeschool environment need to create opportunities for the child to learn how to relate with others in order for social skills to develop. This can be done through community organizations or through cooperative homeschooling activities such as park days, field trips, or working with other families to create co-op classes.

Medlin[8] has encouraged three goals relating to socialization for home educators:

- Participation of homeschooled children in daily routines of their local communities

- Acquisition of rules of behavior and systems of beliefs and attitudes needed both during their education and later in life

- Ability to function effectively as contributing members of society

These goals can help guide parents in finding and planning activities that can encourage a concern for others no matter where they live.

In 2003, the National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI) conducted a survey of over 7,300 U.S. adults who had been home-educated (over 5,000 for more than seven years). Their findings indicated that home education led to high levels of community involvement when compared to those educated in schools:

- Home-educated graduates are active and involved in their communities. 71 percent participate in an ongoing community service activity, like coaching a sports team, volunteering at a school, or working with a church or neighborhood association, compared with 37 percent of U.S. adults of similar ages from a traditional education background.

- Home-educated graduates are more involved in civic affairs and vote in much higher percentages than their peers. For example, 76 percent of surveyed between the ages of 18 and 24 voted within the last five years, compared with only 29 percent of the relevant U.S. population. The numbers of home-educated graduates who vote are even greater in older age groups, with voting levels not falling below 95 percent, compared with a high of 53 percent for the corresponding U.S. populace.

- Of those adults who were home-educated, 58.9 percent report that they are "very happy" with life (compared with 27.6 percent for the general U.S. population). Moreover, 73.2 percent of homeschooled adults find life "exciting," compared with 47.3 percent of the general population.[5]

Legality of homeschooling

Home education exists legally in many parts of the world. Countries with the most prevalent home education movements include the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Some countries have highly regulated home education programs which are actually an extension of the compulsory school system, while others have outlawed it entirely. In many other countries, while not restricted by law, home education is not socially acceptable or not considered desirable and, therefore, virtually non-existent.

In many countries where home education does not exist legally, underground movements flourish where children are kept out of the compulsory school system and educated at, sometimes considerable, risk. Still, in other countries, while the practice is illegal, the governments do not have the resources to police and prosecute offenders and, as such, it takes place largely in the open.

Home education in the United States is governed by each individual state and therefore regulations vary greatly from one state to another, although it is legal in all 50 states. In some states homeschooling parents are occasionally faced with prosecution under truancy laws. The U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled on homeschooling specifically, but in Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) [9] it supported the rights of Amish parents to keep their children out of public schools for religious reasons. Many other court rulings have established or supported the right of parents to provide home education.

Curriculum requirements vary from state to state. Some states require homeschoolers to submit information about their curriculum or lesson plans. Other states (such as Texas) just require that certain subjects be covered and do not require submission of the curriculum. While many complete curricula are available from a wide variety of secular and religious sources, many families choose to use a variety of resources to cover the required subjects. In fact, it is not uncommon for a homeschooled student to earn a number of college credits from a 2- or 4-year college before completing the 12th grade.

Some states offer public-school-at-home programs. These on-line, or "virtual," public schools (usually "charter" schools) mimic major aspects of the homeschooling paradigm, for example, instruction occurs outside of a traditional classroom, usually in the home. However, students in such programs are truly public school students and are subject to all or most of the requirements of other public school students. Some public-school-at-home programs give parents leeway in curriculum choice; others require use of a specified curriculum. Full parental control over the curriculum and program, however, is a hallmark feature of homeschooling. Taxpayers pay the cost of providing books, supplies, and other needs, for public-school-at-home students, just as they do for conventional public school students. The United States Constitution's prohibition against "establishing" religion applies to public-school-at-home programs, so taxpayer money cannot lawfully be used to purchase a curriculum that is religious in nature.

Homeschooling demographics

According to the U.S. Dept of Education report, there was an increase in homeschooled students overall in the U.S. from 850,000 students in 1999 (1.7 percent of the total U.S. student population) to 1.1 million students in 2003 (2.2 percent of the total U.S. student population).[7]

During this time, homeschooling rates increased among students whose parents have high school or lower education, from 2.0 to 2.7 percent among white students; 1.6 to 2.4 percent among student in grades 6-8; and 0.7 to 1.4 percent among students with only one parent. Race and ethnicity ratios remained "fairly consistent" in this time period, with 2.7 percent of white students homeschooling, 1.3 percent of black students, and 0.7 percent of Hispanic students.

The number of homeschoolers worldwide has been increasing in spite of the fact that homeschooling is illegal in several countries. One of the catalysts for the spread of homeschooling is the internet, where families receive information on the legal status of homeschooling in their country as well as support. According to the Home School Legal Defense Association, homeschooling is legal in many countries, under various conditions.[10]

Homeschooling methodology

There is a wide variety of home education methods and materials. Home education families may adopt a particular educational philosophy such as:

- Charlotte Mason education [11]

- Classical Homeschooling [12]

- Eclectic Homeschooling [13]

- Moore Formula [14]

- Montessori method [15]

- Unit Study Approach [16]

- Unschooling [17]

- Virtual Schooling [18]

- Waldorf education[19]

For sources of curricula and books, the U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics found that 78 percent of homeschool parents utilized "a public library," 77 percent used "a homeschooling catalog, publisher, or individual specialist," 68 percent used "retail bookstore or other store," 60 percent used "an education publisher that was not affiliated with homeschooling." "Approximately half" used curriculum or books from "a homeschooling organization," 37 percent from a "church, synagogue, or other religious institution," and 23 percent from "their local public school or district."[7]

41 percent of homeschoolers in 2003 utilized some sort of distance learning. Approximately 20 percent by way of "television, video or radio," 19 percent via "Internet, e-mail, or the World Wide Web," and 15 percent taking a "correspondence course by mail designed specifically for homeschoolers."

Because home education laws vary widely according to individual government statutes, official curriculum requirements vary.

Home educators take advantage of educational programs at museums, community centers, athletic clubs, after-school programs, churches, science preserves, parks, and other community resources. Many families have memberships in health clubs such as the YMCA or take classes such as martial arts to participate in regular exercise. Secondary school level students often take classes at community colleges, which typically have open admission policies.

Criticism of homeschooling

Opposition to home education comes from varied sources, including organizations of teachers and school districts. Opponents state concerns falling into several broad categories, including: academic quality and completeness; reduced government money for the publicly run schools; socialization of children with peers of different ethnic and religious backgrounds; and fear of religious or social extremism. Opponents view home-educating parents as sheltering their children and denying them opportunities that are their children's right. Some opponents argue that parents with little training in education are less effective in teaching.

Critics have suggested that while home-educated students generally do extremely well on standardized tests,[20] such students are a self-selected group whose parents care strongly about their education and would also do well in a conventional school environment.

Opponents have argued that home education curricula often exclude critical subjects and isolate the student from the rest of society, or presents them with their parents' ideological world views, especially religious ones, rather than the publicly sanctioned worldviews taught at state schools.

Indeed, home-educated student curricula often include many subjects not included in traditional curricula. Some colleges find this an advantage in creating a more academically diverse student body, and proponents argue this creates a more well-rounded and self-sufficient adult. Thus, colleges may recruit home-educated students; many colleges accept equivalency diplomas as well as parent statements and portfolios of student work as admission criteria; others also require SATs or other standardized tests.

Homeschooling and citizenship

Four citizenship education research teams in Asia, Europe, and North America coordinated their activities to produce a joint statement about the future of citizenship education in their regions and throughout the world. [21] The participants expressed the idea of "multidimensional citizenship" encompassing the four components of personal, social, temporal, and spatial. This viewpoint seeks to help students reflect on their behavior and how they relate with other people not only locally but worldwide as well as their relationship to the past and the future. The foundation of multidimensional citizenship is the principles of toleration and cooperation with others including such abilities as conflict resolution, rational argument and debate, environmentalism, respect for human rights, and community service. The teams stated this as the goal for citizenship and their hope is that it can become the philosophical foundation for all schools of the future.

Homeschoolers are involved in combining a different mix of attributes to become good citizens consistent with the idea of mulitdimensional citizenship. The importance of the family is the center of a different definition of citizenship. The family is the basic carrier of culture. The traditions and ways of family life mold the attitudes and values of the wider world, influencing everything from tastes in movies, art, and literature to choice of political leaders. Therefore, the family’s practice and example are the starting points for circulating values to the culture.

Children with strong family relationships have the confidence to explore the world in challenging and sometimes unconventional ways. Professional educationalist, Alan Thomas, has expressed the belief that strong family bonds give children the opportunity to learn at their own pace, to sustain a greater level of curiosity, and to follow the intense learning processes:

At home…children spend most of their time at the frontiers of their learning. Their parents are fully aware of what they already know and of the next step to be learned. Learning is therefore more demanding and intensive." [22]

A strong family can give students the ability and the confidence to be more independent and to think responsibly. A primary goal for homeschoolers is to raise children who are willing and able to think for themselves.[23] Students can create the heart of purposeful and informed contribution to the larger society, especially later in life, when there is a strong bond in the family. [24]

Homeschooling can foster the form and content of citizenship education if parents create a strong family bond and share the vision of participating in public activities as the basis of their understanding of the good citizen. For instance, facts about national history and governance are crucial for informed participation in a democracy.

Homeschooling parents and children are helping to define and shape what it means to be a citizen of their country. They must be prepared to have a broad vision and to be aware that homeschooling is not just about where their children will receive their education but it can affect the very definition of what it means to be a member of a society.

Notes

- ↑ Murray N. Rothbard, Education: Free and Compulsory, Mises Daily, September 09, 2006. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Patrick Farenga, A Brief History of Homeschooling, HomeSchool Base, 2002. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Mitchell Stevens, Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001, ISBN 0691058180)

- ↑ Patricia M. Lines, Homeschooling, ERIC Digest, 2001. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Home School Legal Defense Association, Homeschooling Grows Up Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Kurt J. Bauman, Home Schooling in the United States: Trends and Characteristics United States Census Bureau, Working Paper Number POP-WP053, August 2001. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Home Schooling in the United States: Trends and Characteristics National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 2003. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ R.G. Medlin, "Home schooling and the question of socialization," Peabody Journal of Education 75(1 & 2)(2000): 107-123

- ↑ Wisconsin v. Yoder 406 U.S. 205 (1972), The Oyez Project. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Homeschooling in Your Country, Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA). Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ What is the Charlotte Mason Method? Simply Charlotte Mason. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Classical Homeschool A2Z Homeschooling. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Eclectic Homeschool Method A2Z Homeschooling. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Moore Formula Moore Academy. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Montessori Materials & Learning Environments for the home and the school The International Montessori Index. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Unit Study Homeschool Method A2Z Homeschooling. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Earl Stevens, What is Unschooling?, The Natural Child Project, 1994. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Amanda Paulson, Virtual schools, real concerns The Christian Science Monitor, May 4, 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Waldorf Homeschooling Method A2Z Homeschooling. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Christopher J. Klicka, Academic Statistics on Homeschooling, Home School Legal Defense Association, 2004. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ↑ John Cogan and Ray Derricott, Citizenship for the 21st Century: An International Perspective on Education (London: Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0749425121), 115–134, 155-168

- ↑ Alan Thomas, Educating Children at Home (Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998, ISBN 0826452051).

- ↑ J.G. Knowles, "Parents' Rationales for Operating Home Schools" Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 20(2)(1991): 203-230

- ↑ Susanna Sheffer, A Sense of Self: Listening to Homeschooled Adolescent Girls (Boynton/Cook, 1997, ISBN 0867094052).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Harold. No More Public School. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 1972. ISBN 0394707680

- Burton, Warren. Helps to Education In The Homes Of Our Countries. Nabu Press, 2010 (original 1863). ISBN 1146850921

- Cogan, John, and Ray Derricott (eds.). Citizenship for the 21st Century: An International Perspective on Education. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0749425121

- Goodrich, Samuel Griswold. Fireside Education. HardPress Publishing, 2019 (original 1838). ISBN 978-0461086263

- Holt, John. Instead of Education: Ways to Help People do Things Better. Sentient Publications, 2003 (original 1976). ISBN 1591810094

- Illich, Ivan. Deschooling Society. Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 2000, (original 1970) ISBN 0714508799

- Knowles, J.G. "Parents' Rationales for Operating Home Schools." Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 20(2)(1991): 203-230

- Medlin, R.G. "Home schooling and the question of socialization." Peabody Journal of Education 75(1 & 2)(2000): 107-123

- Moore, Raymond S., and Dorothy N. Moore. Home Grown Kids. W Pub Group, 1984. ISBN 0849930073

- Moore, Raymond S., and Dorothy N. Moore. Better Late Than Early. Reader's Digest Association, 1989. ISBN 0883490498

- Sheffer, Susanna. A Sense of Self: Listening to Homeschooled Adolescent Girls. Boynton/Cook, 1997. ISBN 0867094052

- Stevens, Mitchell. Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 0691058180

- Thomas, Alan. Educating Children at Home. Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998. ISBN 0826452051

External Links

All links retrieved July 18, 2024.

- Homeschooling: Back to the Future? by Isabel Lyman, the Cato Institute.

- National Home Education Research Institute

- Home Education Network Victoria, Australia

- Home Education Foundation New Zealand

- National Independent Study Accreditation Council

- School Legal Defense Association

- Homeschool Central

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.