Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (November 14, 1889 – May 27, 1964) was a political leader of the Indian National Congress, a leader of the Indian independence movement and first Prime Minister of the Republic of India. Popularly referred to as Panditji (Scholar), Nehru was also a writer, scholar, and amateur historian, and the patriarch of India's most influential political family.

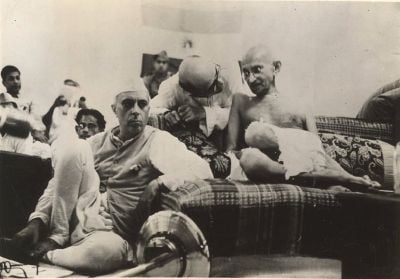

As the son of the wealthy Indian barrister and politician Motilal Nehru, Nehru had become one of the youngest leaders of the Indian National Congress. Rising under the mentorship of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru became a charismatic, radical leader, advocating complete independence from the British Empire. An icon for Indian youth, Nehru was also an exponent of socialism as a means to address long-standing national challenges. Serving as Congress President, Nehru raised the flag of independent India in Lahore on December 31, 1929. A forceful and charismatic orator, Nehru was a major influence in organizing nationalist rebellions and spreading the popularity of the nationalist cause to India's minorities. Elected to lead free India's government, Nehru would serve as India's prime minister and head of the Congress until his death.

As India's leader, Nehru oversaw major national programs of industrialization, agrarian and land reforms, infrastructure and energy development. He passionately worked for women's rights, secularism, and advancement of education and social welfare. Nehru initiated the policy of non-alignment and developed India's foreign policy under the ideals of Pancasila. However, he was criticized for failure of leadership during the Sino-Indian War in 1962. Later after his successor Lal Bahadur Shastri's demise, Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi, would go on to lead the Congress and serve as prime minister, as would his grandson Rajiv. Rajiv's widow Sonia and her children lead the Congress today, maintaining the Nehru-Gandhi family's prominence in Indian politics.

Early life

Jawaharlal Nehru was born in the city of Allahabad, situated along the banks of the Ganges River (now in the state of Uttar Pradesh). Jawahar means a "gem" in Arabic and is a name similar in meaning to moti, "pearl". He was the eldest child of Swarup Rani, the wife of wealthy barrister Motilal Nehru. The Nehru family descended from Kashmiri heritage and belonged to the Saraswat Brahmin caste of Hindus. Training as a lawyer, Motilal had moved to Allahabad and developed a successful practice and had become active in India's largest political party, the Indian National Congress. Nehru and his sisters — Vijaya Lakshmi and Krishna — lived in a large mansion called "Anand Bhavan" and were raised with English customs, manners and dress. While learning Hindi and Sanskrit, the Nehru children would be trained to converse fluently and regularly in English.

After being tutored at home and attending some of the most modern schools in India, Nehru would travel to England at the age of 15 to attend the Harrow School. He would proceed to study natural sciences at the Trinity College before choosing to train as a barrister at the Middle Temple in London. Frequenting the theatres, museums and opera houses of London, he would spend his vacations travelling across Europe. Observers would later describe him as an elegant, charming young intellectual and socialite. Nehru would also participate actively in the political activities of the Indian student community, growing increasingly attracted to socialism and liberalism, which were beginning to influence the politics and economies of Europe.

Upon his return to India, Nehru's marriage was arranged with Kamala Kaul. Married on February 8, 1916, Nehru age was 27 and his bride was 16 years old. The first few years of their marriage were hampered by the cultural gulf between the anglicized Nehru and Kamala, who observed Hindu traditions and focused on family affairs. The following year Kamala would give birth to their only child, their daughter Indira Priyadarshini. Having made few attempts to establish himself in a legal practice, Nehru was immediately attracted to Indian political life, which at the time was emerging from divisions over World War I. The moderate and extremist factions of the Congress had reunited in its 1916 session in Lucknow, and Indian politicians had demanded Home Rule and dominion status for India. Joining the Congress under the patronage of his father, Nehru grew increasingly disillusioned with the liberal and anglicized nature of Congress politicians, which included his father.

Young leader

Nehru was very strongly attracted to Gandhi's philosophy and leadership. Gandhi had led a successful rebellion on behalf of indentured Indian workers while a lawyer in South Africa. Upon his return to India, Gandhi organized the peasants and farmers of Champaran and Kheda in successful rebellions against oppressive tax policies levied by the British. Gandhi espoused what he termed as satyagraha — mass civil disobedience governed by ahimsa, or complete non-violence. A forceful exponent of Indian self-reliance, Gandhi's success electrified Indians, who had been divided in their approach to contesting British rule. Having met Gandhi and learning of his ideas, Nehru would assist him during the Champaran agitation.

Following Gandhi's example, Nehru and his family abandoned their Western-style clothes, possessions and wealthy lifestyle. Wearing clothes spun out of khadi, Nehru would emerge as one of the most energetic supporters of Gandhi. Under Gandhi's influence, Nehru began studying the Bhagavad Gita and would practice yoga throughout his life. He would increasingly look to Gandhi for advice and guidance in his personal life, and would spend a lot of time travelling and living with Gandhi. Nehru travelled across India delivering political speeches aimed at recruiting India's masses, especially its youth into the agitation launched in 1919 against the Rowlatt Acts and the Khilafat struggle. He spoke passionately and forcefully to encourage Hindu-Muslim unity, spread education and self-reliance and the need to eradicate social evils such as untouchability, poverty, ignorance, and unemployment.

Emerging as a key orator and prominent organizer, Nehru became one of the most popular political leaders in northern India, especially with the people of the United Provinces, Bihar and the Central Provinces. His youth and passion for social justice and equality attracted India's Muslims, women and other minorities. Nehru's role grew especially important following the arrest of senior leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru's father, and he would also be imprisoned along with his mother and sisters for many months. Alarmed by growing violence in the conduct of mass agitations, Gandhi suspended the struggle after the killing of 22 state policemen by a mob at Chauri Chaura on February 4, 1922. This sudden move disillusioned some, including Nehru's father, Motilal, who would join the newly formed Swaraj Party in 1923. However, Nehru remained loyal to Gandhi and publicly supported him.

A lull in nationalist activities enabled Nehru to turn his attention to social causes and local government. In 1924, he was elected president of the municipal corporation of Allahabad, serving as the city's chief executive for two years. Nehru would launch ambitious schemes to promote education, sanitation, expand water and electricity supply and reduce unemployment — his ideas and experience would prove valuable to him when he assumed charge of India's government in 1947. Achieving some success, Nehru was dissatisfied and angered by the obstruction of British officials and corruption amongst civil servants. He would resign from his position within two years.

In the early part of the decade, his marriage and family life had suffered owing to the constant activity on his part and that of his father. Although facing domestic pressures and tensions in the absence of her husband, Kamala would increasingly travel with Nehru, address public meetings and seek to sponsor and encourage nationalist activities in her hometown. In the late 1920s, the initial marital gulf between the two disappeared and the couple would grow closer to each other and their daughter. In 1926 Nehru took his wife and daughter to Europe so that Kamala could receive specialized medical care. The family travelled and lived in England, Switzerland, France and Germany. Continuing his political work, Nehru would be deeply impressed by the rising currents of radical socialism in Europe, and would deliver fervent speeches in condemnation of imperialism. On a visit to the Soviet Union, Nehru was favorably impressed by the command economy, but grew critical of Stalin's totalitarianism.

Rise to national leadership

In the 1920s, Nehru was elected president of the All India Trade Unions Congress. He and Subhash Chandra Bose had become the most prominent youth leaders, and both demanded the outright political independence of India. Nehru criticized the Nehru Report prepared by his father in 1928, which called for dominion status for India within the British Empire. The radicalism of Nehru and Bose would provoke intense debates during the 1928 Congress session in Guwahati. Arguing that India would deliver an ultimatum to the British and prepare for mass struggle, Nehru and Bose won the hearts of many young Indians. To resolve the issue, Gandhi said that the British would be given two years to grant India dominion status. If they did not, the Congress would launch a national struggle for full political independence. Nehru and Bose succeeded in reducing the statutory deadline to one year.

The failure of talks with the British caused the December 1929 session in Lahore to be held in an atmosphere charged with anti-Empire sentiment. Preparing for the declaration of independence, the AICC elected Jawaharlal Nehru as Congress President at the encouragement of Gandhi. Favored by Gandhi for his charismatic appeal to India's masses, minorities, women and youth, the move nevertheless surprised many Congressmen and political observers. Many had demanded that Gandhi or the leader of the Bardoli Satyagraha, Vallabhbhai Patel, assume the presidency, especially as the leader of the Congress would the inaugurator of India's struggle for complete freedom. Nehru was seen by many, including himself, as too inexperienced for the job of leading India's largest political organization:

"I have seldom felt quite so annoyed and humiliated…. It was not that I was not sensible of the honour…. But I did not come to it by the main entrance or even the side entrance: I appeared suddenly from a trap door and bewildered the audience into acceptance."

On December 31, 1929 President Nehru hoisted the flag of independence before a massive public gathering along the banks of the Ravi River. The Congress would promulgate the Purna Swaraj (Complete Independence) declaration on January 26, 1930. With the launching of the Salt Satyagraha in 1930, Nehru travelled across Gujarat and other parts of the country participating and encouraging in the mass rebellion against the salt tax. Despite his father's death in 1931, Nehru and his family remained at the forefront of the struggle. Arrested with his wife and sisters, Nehru would be imprisoned for all but four months between 1931 and 1935.

"Quit India"

Nehru was released by the British and he traveled with his family once again to Europe in 1935, where Kamala his ailing wife, would remain bed-ridden. Torn between the freedom struggle and tending to his wife, Nehru would travel back and forth between India and Europe. Kamala Nehru died in 1938. Deeply saddened, Nehru nevertheless continued to maintain a hectic schedule. He would always wear a fresh rose in his coat for the remainder of his life to remember Kamala, who had also become a national heroine.

Nehru had been re-elected Congress President in 1936, and had presided over its session in Lucknow. Here he participated in a fierce debate with Gandhi, Patel and other Congress leaders over the adoption of socialism as the official goal of the party. Younger socialists such as Jaya Prakash Narayan, Mridula Sarabhai, Narendra Dev and Asoka Mehta began to see Nehru as leader of Congress socialists. Under their pressure, the Congress passed the Avadi Resolution proclaiming socialism as the model for India's future government. Nehru was re-elected the following year, and oversaw the Congress national campaign for the 1937 elections. Largely leaving political organization work to others, Nehru traveled the length and breadth of the country, exhorting the masses on behalf of the Congress, which would win an outright majority in the central and most of the provincial legislatures. Although he did not contest elections himself, Nehru was seen by the national media as the leader of the Congress.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Assemblies were informed that the Viceroy had unilaterally declared war on the Axis on behalf of India, without consulting the people's representatives. Outraged at the viceroy's arbitrary decision, all elected Congressmen resigned from their offices at the instigation of Subhash Bose and Nehru. But even as Bose would call for an outright revolt and would proceed to seek the aid of Nazi Germany and Japan, Nehru remained sympathetic to the British cause. He joined Maulana Azad, Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari and Patel in offering Congress support for the war effort in return for a commitment from the British to grant independence after the war. In doing so, Nehru broke ranks with Gandhi, who had resisted supporting war and remained suspicious of the British. The failure of negotiations and Britain's refusal to concede independence outraged the nationalist movement. Gandhi and Patel called for an all-out rebellion, a demand that was opposed by Rajagopalachari and resisted by Nehru and Azad. After intensive debates and heated discussions, the Congress leaders called for the British to Quit India — to transfer power to Indian hands immediately or face a mass rebellion. Despite his skepticism, Nehru traveled the country to exhort India's masses into rebellion. He was arrested with the entire Congress Working Committee on August 9, 1942 and transported to a maximum security prison at a fort in Ahmednagar. Here he would remain incarcerated with his colleagues till June 1945. His daughter Indira and her husband Feroze Gandhi would also be imprisoned for a few months. Nehru's first grandchild, Rajiv was born in 1944.

Nehru and the British

Reflecting in his Discovery of India, Nehru observed that, like many English educated Indians, trained by the British to meet Lord Macaulays's ideal of Indians who would be English in taste, dress and in their ideas but Indian by race, it was from the English that he learned about justice, liberty and concern for the deprived. Citing from Rabindranth Tagore, whom he admired, he wrote of how "English literature nourished" his mind, and "even now conveys its deep resonance." [1] "The parting of the ways" from the British came 'with a powerful sense of disillusionment" when Nehru and a whole class of Indians realized that the British practiced justice at home but not in India. When, Nehru wrote, "it became clear that" the British "did not want us as friends and colleagues but as a slave people to do their bidding," [2] the idea of some continued relationship with Britain was exchanged for the goal of complete independence. Nehru, however, differed from his friend and colleague Gandhi and was closer to Tagore in believing that India could and must learn from the West: "India … must learn from the West, for the modern West has much to teach". However, the West, he insisted, also had much to learn from India. [3] He blamed the British for stunting technological development in India: "India's growth was checked and as a consequence social growth was also arrested."[1]

India's first prime minister

Nehru and his colleagues had been released as the British Cabinet Mission arrived to propose plans for transfer of power. The Congress held a presidential election in the knowledge that its chosen leader would become India's head of government. Eleven Congress state units nominated Vallabhbhai Patel, while only the Working Committee suggested Nehru. Sensing that Nehru would not accept second place to Patel, Gandhi supported Nehru and asked Patel to withdraw, which he immediately did. Nehru's election surprised many Congressmen and continues to be a source of controversy in modern times. Nehru headed an interim government, which was impaired by outbreaks of communal violence and political disorder, and the opposition of the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who were demanding a separate Muslim state of Pakistan. After failed bids to form coalitions, Nehru reluctantly supported the partition of India as per a plan released by the British on June 3, 1947. He would take office as the Prime Minister of India on August 15, and delivered his inaugural address titled "A Tryst With Destiny:"

"Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity."[4]

However, this period was marked with intense communal violence. This violence swept across the Punjab region, Delhi, Bengal and other parts of India. Nehru conducted joint tours with Pakistani leaders to encourage peace and calm angry and disillusioned refugees. Nehru would work with Maulana Azad and other Muslim leaders to safeguard and encourage Muslims to remain in India. The violence of the time deeply affected Nehru, who called for a ceasefire and U.N. intervention to stop the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947. Fearing communal reprisals, Nehru also hesitated in supporting the annexation of Hyderabad State, and clashed with Patel on the Kashmir dispute and relations with Pakistan. Nehru asserted his own control over Kashmir policy while Patel objected to Nehru sidelining his Home Ministry's officials.[5] Nehru felt offended by Patel's decision-making regarding the states' integration without consulting either him or the Cabinet. Patel asked Gandhi to relieve him of his obligation to serve. He knew that he lacked Nehru's youth and popularity, and believed that an open political battle would hurt India. After much personal deliberation and contrary to Patel's prediction, Gandhi on 30 January, 1948 told Patel not to leave the Government, and to stay by Nehru's side in joint leadership. A free India, according to Gandhi, desperately needed both Patel and Nehru's joint leadership.[6]

Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948. At Gandhi's wake, Nehru and Patel embraced each other and addressed the nation together. Criticism soon arose from the media and other politicians that Patel's home ministry had failed to protect Gandhi. Emotionally exhausted, Patel tendered a letter of resignation, offering to leave the Government — despite his word to Gandhi — desiring not to embarrass Nehru's administration. Nehru sent Patel a letter dismissing any question of personal differences and his desire for Patel's ouster. He reminded Patel of their 30-year partnership in the freedom struggle, and that after Gandhi's death, it was especially wrong for them to quarrel. Moved, Patel personally and publicly endorsed Nehru's leadership and refuted any suggestion of discord. Despite working together, the two leaders would clash on various issues. Nehru declined Patel's counsel on sending assistance to Tibet in 1950 with the disputed entrance of the People's Republic of China and ejecting the Portuguese from Goa by military force.[7]

When Nehru pressured Dr. Rajendra Prasad to decline a nomination to become the first President of India in 1950 in favor of Rajagopalachari, he thus angered the party, which felt Nehru was attempting to impose his will. Nehru sought Patel's help in winning the party over, but Patel declined, and Prasad was duly elected. When Nehru opposed the 1950 Congress presidential candidacy of Purushottam Das Tandon, a conservative Hindu leader, he endorsed Jivatram Kripalani and threatened to resign if Tandon was elected. Patel rejected Nehru's views and endorsed Tandon in Gujarat, in a disputed election where Kripalani received not one vote despite hailing from that state himself.[8] Patel believed Nehru had to understand that his will was not law with the Congress, but he personally discouraged Nehru from resigning after the latter felt that the party had no confidence in him.[9]

Leading India

In the years following independence, Nehru frequently turned to his daughter Indira to look after him and manage his personal affairs. Following Patel's death in 1950, Nehru became the most popular and powerful Indian politician. Under his leadership, the Congress won an overwhelming majority in the elections of 1952, in which his son-in-law Feroze Gandhi was also elected. Indira moved into Nehru's official residence to attend to him, inadvertently estranging her husband, who would become a critic of Nehru's government. Nevertheless, Indira would virtually become Nehru's chief of staff and constant companion in his travels across India and the world.

Nehru's Socialist vision

Believing that British colonialism had stunted India's economic growth and that colonialism was a product of capitalism, Nehru always preferred "non capitalist solutions."[10] He was also unwilling to trust the rich to improve the life conditions of the poor. Looking with admiration towards the USSR, he attributed the communist system with having brought "about the industrialization and modernization of a large, feudal and backward multinational state not unlike his own." [10] Along with other socialist inclined intellectuals, he too thought that centralization and state planning of the economy were the "scientific" and "rational means of creating social prosperity and ensuring its equitable distribution." This was the type of socialism that he took to his governing of India.

Economic policies

Nehru implemented his socialist vision by introducing a modified, "Indian" version of state planning and control over the economy. Creating the Planning Commission of India, Nehru drew up the first Five-Year Plan in 1951, which charted the government's investments in industries and agriculture. Increasing business and income taxes, Nehru envisaged a mixed economy in which the government would manage strategic industries such as mining, electricity and heavy industries, serving public interest and a check to private enterprise. Nehru pursued land redistribution and launched programmes to build irrigation canals, dams and spread the use of fertilizers to increase agricultural production. He also pioneered a series of community development programs aimed at spreading diverse cottage industries and increasing efficiency into rural India. While encouraging the construction of large dams, irrigation works and the generation of hydroelectricity, Nehru also launched India's programme to harness nuclear energy.

For most of Nehru's term as prime minister, India would continue to face serious food shortages despite progress and increases in agricultural production. Nehru's industrial policies encouraged the growth of diverse manufacturing and heavy industries, yet state planning, controls and regulations impaired productivity, quality and profitability. Although the Indian economy enjoyed a steady rate of growth, chronic unemployment amidst entrenched poverty continued to plague the population. Nehru's popularity remained unaffected, and his government succeeded in extending water and electricity supply, health care, roads and infrastructure to a large degree for India's vast rural population.

A few of Nehru's ministers had to resign on allegations of corruption. His Minister of Mines and Oil, K. D. Malviya, had to resign for accepting money from a private party in return for certain concessions. The sitting judge of the Supreme Court, S. K. Das, reviewed all the evidence, including the account books of the businessman in which mention had been made of a payment to Malviya, and found two of the six charges against the Minister to be valid. Malviya resigned as a result.

Education and social reform

Jawaharlal Nehru was a passionate advocate of education for India's children and youth, believing it essential for India's future progress. His government oversaw the establishment of many institutions of higher learning, including the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the Indian Institutes of Technology and the Indian Institutes of Management. Nehru also outlined a commitment in his five-year plans to guarantee free and compulsory primary education to all of India's children. For this purpose, Nehru oversaw the creation of mass village enrollment programmes and the construction of thousands of schools. Nehru also launched initiatives such as the provision of free milk and meals to children in order to fight malnutrition. Adult education centres, vocational and technical schools were also organized for adults, especially in the rural areas.

Under Nehru, the Indian Parliament enacted many changes to Hindu law to criminalize caste discrimination and increase the legal rights and social freedoms of women. A system of reservations in government services and educational institutions was created to eradicate the social inequalities and disadvantages faced by peoples of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Nehru also championed secularism and religious harmony, increasing the representation of minorities in government.

National security and foreign policy

Although having promised in 1948 to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir under the auspices of the U.N., Nehru grew increasingly wary of the U.N. and declined to hold a plebiscite in 1953. He ordered the arrest of the Kashmiri politician Sheikh Abdullah, whom he had previously supported but now suspected of harboring separatist ambitions; Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad replaced him. On the international scene, Nehru was a champion of pacifism and a strong supporter of the United Nations. He pioneered the policy of non-alignment and co-founded the Non-Aligned Movement of nations professing neutrality between the rival blocs of nations led by the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Recognizing the People's Republic of China soon after its founding (while most of the Western bloc continued relations with the Republic of China), Nehru sought to establish warm and friendly relations with it despite the invasion of Tibet in 1950, and hoped to act as an intermediary to bridge the gulf and tensions between the communist states and the Western bloc.

Nehru was hailed by many for working to defuse global tensions and the threat of nuclear weapons. In 1956 he had criticized the joint invasion of the Suez Canal by the British, French and Israelis. Suspicion and distrust cooled relations between India and the U.S., which suspected Nehru of tacitly supporting the Soviet Union. Accepting the arbitration of the United Kingdom and World Bank, Nehru signed the Indus Water Treaty in 1960 with Pakistani ruler Ayub Khan to resolve long-standing disputes about sharing the resources of the major rivers of the Punjab region.

Chinese miscalculation

Nehru assumed that as former colonies India and China shared a sense of solidarity, as expressed in the phrase "Hindi-Chini bhai bhai" (Indians and Chinese are brothers). He was dedicated to the ideals of brotherhood and solidarity among developing nations, while China was dedicated to a realist vision of itself as the hegemon of Asia. Nehru did not believe that one fellow socialist country would attack another; and in any event, he felt secure behind the impregnable wall of ice that is the Himalayas. Both proved to be tragic miscalculations of China's determination and military capabilities. Nehru decided to adopt the policy of moving his territory forward, and refused to consider any negotiations China had to offer. As Nehru declared the intention to throw every Chinese out of the disputed areas, China made a preemptive attack on the Indian front. India was vanquished by the Chinese People's Liberation Army in a bitter and cold battle in the Northeast.

Although India has repaired its relationship with the Chinese government to some extent, the wounds of the Sino-Indian War have not been forgotten. Even today, over 45 years later, few know the real story of what happened and what went wrong. The military debacle against China in 1962 was thoroughly investigated in the Henderson-Brooks Report which successive Indian governments have refused to release.

In a separate instance, it was a revelation when in an interview given to the BBC by the former Indian Defence Minister of India, George Fernandes, when he said that the Coco Islands were part of India until they were given to Burma (Myanmar) by Nehru. The Coco Islands are located 18 km from the Indian archipelago of Nicobar. At present, China reportedly has an intelligence gathering station on Great Coco Island to monitor Indian naval activity in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands archipelago as well as ISRO space launch activities from Sriharikota and DRDO missile tests from Chandipur-on-sea.

Nehru and technology

Unlike Gandhi, who wanted to draw almost exclusively on India's traditions to achieve self-reliance, Nehru wanted to combine the best of what India offered with Western technology, which was closer to Tagore's vision. He was ambitious for India; "there was no limit," says Tharoor, "to his scientific aspirations for India."[11] Tharoor says, however, that while on the one hand his economic planning created "an infrastructure for excellence in science and technology" which has become "a source of great self-confidence" for India, on the other his reluctance to allow inward investment in India has left much of the nation "moored in the bicycle age."[11]

Final years

Nehru had led the Congress to a major victory in the 1957 elections, but his government was facing rising problems and criticism. Disillusioned by intra-party corruption and bickering, Nehru contemplated resigning but continued to serve. The election of his daughter Indira as Congress President in 1959 aroused criticism for alleged nepotism. Although the Pancha Sila (Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence) was the basis of the 1954 Sino-Indian treaty over Tibet, in later years, Nehru's foreign policy suffered through increasing Chinese antagonism over border disputes and Nehru's decision to grant asylum to the Dalai Lama. After years of failed negotiations, Nehru authorized the Indian Army to annex Goa from Portugal in 1961. While increasing his popularity, Nehru received criticism for opting for military action.

In the 1962 elections, Nehru led the Congress to victory yet with a diminished majority. Opposition parties ranging from the right-wing Bharatiya Jana Sangh and Swatantra Party, socialists and the Communist Party of India performed well. In a matter of months, a Chinese invasion of northeastern India exposed the weaknesses of India's military as Chinese forces came as far as Assam. Widely criticized for neglecting India's defence needs, Nehru was forced to sack the defence minister Krishna Menon and accept U.S. military aid. Nehru's health began declining steadily, and he was forced to spend months recuperating in Kashmir through 1963. Upon his return from Kashmir in May 1964, Nehru suffered a stroke and later a heart attack. He died on May 27, 1964. Nehru was cremated as per Hindu rites at the Shantivana on the banks of the Yamuna River, witnessed by hundreds of thousands of mourners who had flocked into the streets of Delhi and the cremation grounds.

Legacy

Jawaharlal Nehru has been criticized for refusing to accept Vallabhbhai Patel as the Congress nominee to lead India's government. Some historians suggest that Nehru refused to take a second place in the national government and may have threatened to split the Congress party. While the state Congress Working Committees, though not the Central Working Committee, believed that Patel was better suited for the office, prominent observers such as the industrialist J. R. D. Tata and contemporary historians suggest that Patel would have been more successful than Nehru in tackling India's problems.

Nehru is criticized for establishing an era of socialist policies that created a burgeoning, inefficient bureaucracy (which inhibits India to this day) and curbed free enterprise and productivity while failing to significantly eliminate poverty, shortages and poor living conditions. Historians and Hindu nationalists also criticize Nehru for allegedly appeasing the Indian Muslim community at the expense of his own conviction in secularism. Nehru's declaratory neutral foreign policy is criticized as hypocritical due to his affinity for the Soviet Union and other socialist states. He is also blamed for ignoring the needs of India's military services and failing to acknowledge the threat posed by the People's Republic of China and Pakistan. Many believe India would not have had as difficult a time in facing the challenges of the twenty-first century had Patel been Prime Minister and Nehru retained as External Affairs Minister, which was his forte. However, perhaps his shortcomings are compensated by his strong democratic principles, which set down such firm roots in post-1947 India that India's democracy has proved to be robust and solid in the face of emergencies, wars and other crises.

As India's first prime minister and external affairs minister, Nehru played a major role in shaping modern India's government and political culture along with sound foreign policy. He is praised for creating a system providing universal primary education, reaching children in the farthest corners of rural India. Nehru's education policy is also credited for the development of world-class educational institutions. Nehru is credited for establishing a widespread system of affirmative action to provide equal opportunities and rights for India's ethnic groups, minorities, women, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Nehru's passion for egalitarianism helped end widespread practices of discrimination against women and depressed classes. Nehru is widely lauded for pioneering non-alignment and encouraging a global environment of peace and security amidst escalating Cold War tensions.

Commemoration

In his lifetime, Jawaharlal Nehru enjoyed an iconic status in India and was widely admired across the world for his idealism and statesmanship. His birthday, November 14, is celebrated in India as Children's Day in recognition of his lifelong passion and work for the welfare, education and development of children and young people. Children across India are taught to remember him as Chacha Nehru (Uncle Nehru). Nehru remains a popular symbol of the Congress Party, which frequently celebrates his memory. Congress leaders and activists often emulate his style of clothing, especially the Gandhi cap, and his mannerisms. Nehru's ideals and policies continue to shape the Congress Party's manifesto and core political philosophy. An emotional attachment to his legacy was instrumental in the rise of his daughter, Indira, to leadership of the Congress Party and the national government.

Many documentaries about Nehru's life have been produced. He has also been portrayed in fictionalized films. Nehru's character in Richard Attenborough's 1982 film Gandhi was played by Roshan Seth. In Ketan Mehta's film Sardar, Nehru was portrayed by Benjamin Gilani.

Numerous public institutions and memorials across India are dedicated to Nehru's memory. The Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi is among the most prestigious universities in India. The Jawaharlal Nehru Port near the city of Mumbai is a modern port and dock designed to handle a huge cargo and traffic load. Nehru's residence in Delhi is preserved as the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. The Nehru family homes at Anand Bhavan and Swaraj Bhavan are also preserved to commemorate Nehru and his family's legacy. In 1951, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC).[12]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India (Penguin Books, 2004 (original 1960), ISBN 978-0143031031), 321-322.

- ↑ Nehru, 430.

- ↑ Nehru, 507

- ↑ Jawaharlal Nehru, A Tryst with Destiny Wikisource. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life (Navajivan Pub. House, 1990, ISBN 978-8172291389), 459.

- ↑ Gandhi, 467.

- ↑ Gandhi, 508-512.

- ↑ Gandhi, 523-524.

- ↑ Gandhi, 504-506.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Shashi Tharoor, Nehru: The Invention of India (NY: Arcade Books, 2003, ISBN 155970697X), 240.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tharoor, 213.

- ↑ Nobel Peace Prize nominations 'American Friends Service Committee. retrieved November 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Judith M. Nehru: A political life. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0300114072

- Gandhi, Rajmohan. Patel: A Life. Navajivan Pub. House, 1990. ISBN 978-8172291389

- Gopal, S., and Uma Iyengar (eds.). The Essential Writings of Jawaharlal Nehru NY: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195653246

- Nehru, Jawaharlal. Toward freedom: The Autobiography of Jawaharlal Nehru. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1941. ASIN B000KUJ74A

- Nehru, Jawaharlal. The Discovery of India. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2004 (original 1960). ISBN 978-0143031031

- Tharoor, Shashi. Nehru: The Invention of India. NY: Arcade Books, 2003. ISBN 155970697X

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964)

- Quotations by Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 - 1964)

- Jawaharlal Nehru University

| |||||

| Indian Independence Movement | |

|---|---|

| History: | Colonisation - British East India Company - Plassey - Buxar - British India - French India - Portuguese India - More... |

| Philosophies: | Indian nationalism - Swaraj - Gandhism - Satyagraha - Hindu nationalism - Indian Muslim nationalism - Swadeshi - Socialism |

| Events and movements: | Rebellion of 1857 - Partition of Bengal - Revolutionaries - Ghadar Conspiracy - Champaran and Kheda - Jallianwala Bagh Massacre - Non-Cooperation - Flag Satyagraha - Bardoli - 1928 Protests - Nehru Report - Purna Swaraj - Salt Satyagraha - Act of 1935 - Legion Freies Indien - Cripps' mission - Quit India - Indian National Army - Bombay Mutiny |

| Organisations: | Indian National Congress - Ghadar - Home Rule - Khudai Khidmatgar - Swaraj Party - Anushilan Samiti - Azad Hind - More... |

| Indian leaders: | Mangal Pandey - Rani of Jhansi - Bal Gangadhar Tilak - Gopal Krishna Gokhale - Lala Lajpat Rai - Bipin Chandra Pal - Mahatma Gandhi - M. Ali Jinnah - Sardar Patel - Subhash Chandra Bose - Badshah Khan - Jawaharlal Nehru - Maulana Azad - Chandrasekhar Azad - Rajaji - Bhagat Singh - Sarojini Naidu - Purushottam Das Tandon - Tanguturi Prakasam - Alluri Sitaramaraju - More... |

| British Raj: | Robert Clive - James Outram - Dalhousie - Irwin - Linlithgow - Wavell - Stafford Cripps - Mountbatten - More... |

| Independence: | Cabinet Mission - Indian Independence Act - Partition of India - Political integration - Constitution - Republic of India |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.