Bhagat Singh

| Bhagat Singh ਭਗਤ ਸਿੰਘ بھگت سنگھہ | |

|---|---|

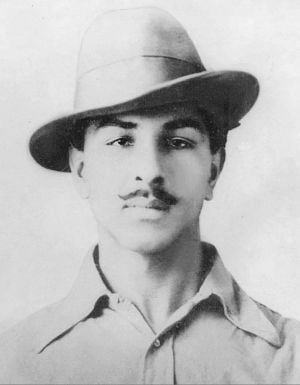

Bhagat Singh at the age of 21 | |

| Place of birth: | Lyallpur, Punjab, British India |

| Place of death: | Lahore, Punjab, British India |

| Movement: | Indian Independence movement |

| Major organizations: | Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Kirti Kissan Party and Hindustan Socialist Republican Association |

Bhagat Singh (Punjabi: ਭਗਤ ਸਿੰਘ بھگت سنگھہ, IPA: [pə˨gət̪ sɪ˦ŋg]) (September 28,[1] 1907–March 23, 1931) fought an Indian freedom fighter, considered one of the most famous revolutionaries of the Indian independence movement. For that reason, Indians often refer to him as Shaheed Bhagat Singh (the word shaheed means "martyr"). Many believe him one of the earliest Marxists in India.[2] He had been one of the leaders and founders of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA).

Born to a family which had earlier been involved in revolutionary activities against the British Raj in India, Bhagat Singh, as a teenager, having studied European revolutionary movements, had been attracted to anarchism and communism.[3] He became involved in numerous revolutionary organizations. He quickly rose in the ranks of the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) and became one of its leaders, converting it to the HSRA. Singh gained support when he underwent a 63-day fast in jail, demanding equal rights for Indian and British political prisoners. Hanged for shooting a police officer in response to the killing of veteran social activist Lala Lajpat Rai, his legacy prompted youth in India to begin fighting for Indian independence and also increased the rise of socialism in India.[4]

Bhagat Singh, given the title "Shaheed" or martyr, grew up at an exciting time for the Independence movement. During his life time, Mahatma Gandhi developed his non-violence philosophy to deal with Indian independence. His philosophy, based in Hindu thought and practice, had compatibility with Buddhism, Jainism, Islam, and Christianity. Bhagat Singh joined Gandhi as a boy, putting into practice Gandhi's non violent resistance teaching. Whereas Gandhi went the way of the spiritual teachings of Hinduism, Buddha, and Christ, Singh went the way of Marx, Engels, and violence. Singh, an atheist and a Marxists, rejected Gandhi's commitment to God and peaceful resistance.

That Bhagat Singh felt angry about British colonial rule is not surprising. Most Indians hated British rule. If Singh could have over thrown the British colonial government and installed his own brand of communism and atheism, India would have been cast into the dark ages. Instead, India by and large rejected Singh's approach and embraced Gandhi's. Due to that wise national decision, India is a vibrant, rapidly developing, spiritually directed nation of one billion people.

Early life

Bhagat Singh had been born into a Sandhu family to Sardar Kishan Singh Sandhu and Vidyavati in the Khatkar Kalan village near Banga in the Lyallpur district of Punjab on September 28, 1907. Singh's given name of Bhagat meant "devotee." His had been a patriotic Sikh family, participating in numerous movements supporting independence of India.[5] The Hindu reformist Arya Samaj influenced his father. His uncles, Ajit Singh and Swaran Singh both took part in the Ghadr Party led by Kartar Singh Sarabha. Ajit Singh fled to Iran to avoid pending legal cases against him while Swaran Singh died from hanging.[6]

As a child, the Jalianwala Bagh Massacre that took place in Punjab in 1919 deeply affected him.[7] When Mahatma Gandhi started the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920, he became an active participant at the age of 13. He had great hopes that Gandhi would bring freedom in India. But he felt disappointed when Gandhi called off that movement following the Chauri Chaura riot in 1922. At that point he had openly defied the British and had followed Gandhi's wishes by burning his government-school books and any British-imported clothing. In 1923, Bhagat famously won an essay competition set by the Punjab Hindi Sahitya Sammelan. That grabbed the attention of members of the Punjab Hindi Sahitya Sammelan including its General Secretary Professor Bhim Sen Vidyalankar. At that age, he quoted famous Punjabi literature and discussed the Problems of the Punjab. He read a lot of poetry and literature written by Punjabi writers, Allama Iqbal, an Indian freedom fighter from Sialkot became his favorite poet.[8]

In his teenage years, Bhagat Singh studying at the National College in Lahore, running away from home to escape early marriage, and became a member of the organization Naujawan Bharat Sabha (Translated to 'Youth Society of India'). In the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Singh and his fellow revolutionaries grew popular amongst the youth. He also joined the Hindustan Republican Association at the request of Professor Vidyalankar, then headed by Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaqulla Khan. He may have had knowledge of the Kakori train robbery. He wrote for and edited Urdu and Punjabi newspapers published from Amritsar.[9] In September 1928, a meeting of various revolutionaries from across India had been called at Delhi under the banner of the Kirti Kissan Party. Bhagat Singh served as the secretary of the meeting. He carried out later revolutionary activities as a leader of that association. The capture and hanging of the main HRA Leaders necessitated his and Sukhdev quick promotion to higher ranks in the party.[10]

Later Revolutionary activities

Lala Lajpat Rai's death and the Saunders murder

The British government created a commission under Sir John Simon to report on the current political situation in India in 1928. The Indian political parties boycotted the commission because Indians had been excluded from representation, protests erupting throughout the country. When the commission visited Lahore on October 30, 1928, Lala Lajpat Rai led the protest against the commission in a silent non-violent march, but the police responded with violence. The police chief beat Lala Lajpat Rai severely and he later succumbed to his injuries. Bhagat Singh, an eyewitness to that event, vowed to take revenge. He joined with other revolutionaries, Shivaram Rajguru, Jai Gopal and Sukhdev Thapar, in a conspiracy to kill the police chief. Jai Gopal had been assigned to identify the chief and signal for Singh to shoot. In a case of mistaken identity, Gopal signaled Singh on the appearance of J. P. Saunders, a Deputy Superintendent of Police. Thus, Singh shot Saunders, instead of Scott.[11] He quickly left Lahore to escape the police. To avoid recognition, he shaved his beard and cut his hair, a violation of one of the sacred tenets of Sikhism.

Bomb in the assembly

In the face of actions by the revolutionaries, the British government enacted the Defence of India Act to give more power to the police. The Act, defeated in the council by one vote, purposed to combat revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh. The Act later passed under the ordinance that claimed the Act served the best interest of the public. In response to that act, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association planned to explode a bomb in the assembly where the ordinance would be passed. Originally, Azad attempted to stop Bhagat Singh from carrying out the bombing; the remainder of the party forced him to succumb to Singh's wishes, deciding that Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt, another revolutionary, would throw the bombs in the assembly.

On April 8, 1929, Singh and Dutt threw bombs onto the corridors of the assembly and shouted "Inquilab Zindabad!" ("Long Live the Revolution!"). A shower of leaflets stating that it takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear followed. The bomb neither killed nor injured anyone; Singh and Dutt claimed they deliberately avoided death and injury, a claim substantiated both by British forensics investigators who found that the bomb too weak to cause injury, and the bomb had been thrown away from people. Singh and Dutt gave themselves up for arrest after the bomb.[12] He and Dutt received life sentences to 'Transportation for Life' for the bombing on June 12, 1929.

Trial and execution

Shortly after his arrest and trial for the Assembly bombing, the British came to know of his involvement in the murder of J. P. Saunders. The courts charged Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev with the murder. Bhagat Singh decided to use the court as a tool to publicize his cause for the independence of India. He admitted to the murder and made statements against the British rule during the trial.[13] The judge ordered the case carried out without members of the HSRA present at the hearing. That created an uproar amongst Singh's supporters as he could no longer publicize his views.

While in jail, Bhagat Singh and other prisoners launched a hunger strike advocating for the rights of prisoners and under trial. They struck to protest better treatment of British murderers and thieves than Indian political prisoners, who, by law, would receive better conditions. They aimed through their strike to ensure a decent standard of food for political prisoners, the availability of books and a daily newspaper, as well as better clothing and the supply of toilet necessities and other hygienic necessities. He also demanded political prisoners' exemption from forced labor or undignified work.[14] During that hunger strike that lasted 63 days and ended with the British succumbing to his wishes, he gained much popularity among the common Indians. Before the strike his popularity had been limited mainly to the Punjab region.[15]

Bhagat Singh also maintained a diary, eventually filling 404 pages, with notes relating to the quotations and popular sayings of various people whose views he supported; Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels held a prominent place.[16] The comments in his diary led to an understanding of the philosophical thinking of Bhagat Singh.[17] Before dying he also wrote a pamphlet entitled "Why I am an atheist," to counter the charge of vanity for rejecting God in the face of death.

On March 23, 1931, the British hanged Bhagat Singh in Lahore with his comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev. His supporters, who had been protesting against the hanging, immediately declared him as a shaheed or martyr.[18] According to the Superintendent of Police at the time, V.N. Smith, the time of the hanging had been advanced:

Normally execution took place at 8 A.M., but it was decided to act at once before the public could become aware of what had happened…. At about 7 P.M. shouts of Inquilab Zindabad were heard from inside the jail. This was correctly interpreted as a signal that the final curtain was about to drop.[19]

Singh had been cremated at Hussainiwala on banks of Sutlej river. Today, the Bhagat Singh Memorial commemorates freedom fighters of India.[20]

Political Thoughts and Opinions

Marxism/Leninism

Bhagat Singh's political thought evolved gradually from Gandhian nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. By the end of 1928, he and his comrades renamed their organization the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. He had read the teachings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin and believed that, with such a large and diverse population, India could only survive properly under a socialist regime. Those ideals had been introduced to him during his time at the National College at Lahore and he believed that India should re-enact the Russian revolution. In the case that India rejected socialism, he believed that the rich would only get richer and the poor would only get poorer. That, and his militant methods, put him at odds with Gandhi and members of the Congress. He became the first socialist leader in India to make any gain. Even today, socialist leaders sometimes refer back to him as the founder of Indian socialism.

Atheism

While in a condemned cell in 1931, he wrote a pamphlet entitled Why I am an Atheist in which he discussed and advocated the philosophy of atheism. That pamphlet arose as a counter to criticism by fellow revolutionaries for his failure to acknowledge religion and God while in a condemned cell, the accusation of vanity. He supported his own beliefs and claimed that he used to be a firm believer in The Almighty, but rejected the myths and beliefs that others held close to their hearts. In that pamphlet, he acknowledged that religion made death easier, but declared unproved philosophy a sign of human weakness.[21]

Death

Bhagat Singh had been known to have an appreciation of martyrdom. Kartar Singh Sarabha had been his mentor as a young boy.[22] Many Indians consider Singh a martyr for acting to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai, also considered a martyr. In the leaflet he threw in the Central Assembly on April 8, 1929, he stated that It is easy to kill individuals but you cannot kill the ideas. Great empires crumbled while the ideas survived.[23] After engaging in studies on the Russian Revolution, he wanted to die so that his death would inspire the youth of India to unite and fight the British Empire.[24]

While in prison, Bhagat Singh and two others had written a letter to the Viceroy asking him to treat them as prisoners of war and hence to execute them by firing squad rather than by hanging. Prannath Mehta visited him in the jail on March 20, four days before his execution, with a draft letter for clemency, but he declined to sign it.[25]

Conspiracy theories

Many conspiracy theories arose regarding Singh, especially the events surrounding his death.

Mahatma Gandhi

One theory contends that Mahatma Gandhi had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but refused. That particular theory has spread among the public in modern times after the creation of modern films such as The Legend of Bhagat Singh, which portray Gandhi as someone strongly at odds with Bhagat Singh and supporting his hanging.[26] In a variation on that theory, Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed. Both highly controversial theories have been hotly contested. Gandhi's supporters say that Gandhi too little influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it. Furthermore, Gandhi's supporters assert that Singh's role in the independence movement posed no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, and so Gandhi would have no reason to want him dead.

Gandhi, during his lifetime, always maintained a great admiration of Singh's patriotism, but that he simply disapproved of his violent methods. He also said that he opposed Singh's execution (and, for that matter, capital punishment in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. On Singh's execution, Gandhi said, "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only."[27] Gandhi also once said, on capital punishment, "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life because He alone gives it."

Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners—members of movements other than his Satyagraha movement—released under the pretext of "relieving political tension," in the Gandhi-Irwin Pact. According to a report in the Indian magazine Frontline, he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentence of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, including a personal visit on March 19, 1931, and in a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, pleading fervently for commutation, without knowing that the letter would be too late.[28]

Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, later said:

As I listened to Mr. Gandhi putting the case for commutation before me, I reflected first on what significance it surely was that the apostle of non-violence should so earnestly be pleading the cause of the devotees of a creed so fundamentally opposed to his own, but I should regard it as wholly wrong to allow my judgment to be influenced by purely political considerations. I could not imagine a case in which under the law, penalty had been more directly deserved.[29]

Spurious book

On October 28, 2005, K.S. Kooner's and G.S. Sindhra's book entitled, Some Hidden Facts: Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh—Secrets unfurled by an Intelligence Bureau Agent of British-India [sic] released. The book asserted that Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev had been deliberately hanged in such a manner as to leave all three in a semi-conscious state, so that all three could later be taken outside the prison and shot dead by the Saunders family, a prison operation codenamed "Operation Trojan Horse." Scholars have expressed skepticism of the book's claims.[30]

Legacy

Indian independence movement

Bhagat Singh's death had the effect that he desired and he inspired thousands of youths to assist the remainder of the Indian independence movement. After his hanging, youths in regions around Northern India rioted in protest against the British Raj.

Modern day legacy

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) itself acknowledges Bhagat Singh's contribution to Indian society[31] and, in particular, the future of socialism in India. To celebrate the centenary of his birth, a group of intellectuals have set up an institution to commemorate Singh and his ideals.[32]

Several popular Bollywood films have been made capturing the life and times of Bhagat Singh. Shaheed, released in 1965, starred Manoj Kumar as Singh. Two major films about Singh released in 2002, The Legend of Bhagat Singh and 23rd March 1931: Shaheed. The Legend of Bhagat Singh represents Rajkumar Santoshi's adaptation, in which Ajay Devgan played Singh and Amrita Rao featured in a brief role. Guddu Dhanoa directed 23 March 1931: Shaheed, starring Bobby Deol as Singh, with Sunny Deol and Aishwarya Rai in supporting roles.

The 2006 film Rang De Basanti (starring Aamir Khan) drew parallels between revolutionaries of Bhagat Singh's era and modern Indian youth. It covers Bhagat Singh's role in the Indian freedom struggle, revolving around a group of college students and how they each play the roles of Bhagat's friends and family.

The patriotic Urdu and Hindi songs, Sarfaroshi ki Tamanna ("the desire to sacrifice") and Mera Rang De Basanti Chola ("my light-yellow-colored cloak") with Basanti referring to the light-yellow color of the Mustard flower grown in the Punjab which is one color of the rehat meryada (code of conduct of the Sikh Saint-Soldier). These songs are largely associated with Bhagat Singh and have been used in a number of films related to him.

In September 2007 the governor of Pakistan's Punjab province announced that a memorial to Bhagat Singh will be displayed at Lahore museum. According to the governor “Singh was the first martyr of the subcontinent and his example was followed by many youth of the time."[33]

Criticism

Both his contemporaries and people after his death criticized Bhagat Singh because of his violent and revolutionary stance towards the British, his opposition to the pacifist stance taken by the Indian National Congress and particularly Mahatma Gandhi.[34] The methods he used to make his point—shooting Saunders and throwing non-lethal bombs—stood in opposition to the non-violent non-cooperation used by Gandhi. The British accused him of having knowledge of the Kakori train robbery.

Bhagat Singh has also been accused of being too eager to die, as opposed to staying alive and continuing his movement. It has been alleged that he could have escaped from prison if he so wished, but he preferred that he die and become a legacy for other youths in India. Some lament that he may have done much more for India had he stayed alive.[35]

Quotations

- "The aim of life is no more to control the mind, but to develop it harmoniously; not to achieve salvation here after, but to make the best use of it here below; and not to realise truth, beauty and good only in contemplation, but also in the actual experience of daily life; social progress depends not upon the ennoblement of the few but on the enrichment of democracy; universal brotherhood can be achieved only when there is an equality of opportunity - of opportunity in the social, political and individual life." — from Bhagat Singh's prison diary, 124

See also

- Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

- Communist Party of India (Marxist)

- Sukhdev Thapar

- Chandrashekar Azad

- Udham Singh

- Rajguru

- Shaheed

Notes

- ↑ Tribune Chandigarh: In memory of Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Communist Party of India (Marxist)

- ↑ Revolutionary Democracy: Bhagat Singh and the Revolutionary Movement

- ↑ Reeta Sharma, Tribune India: What if Bhagat Singh had lived Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Bharat Desam Biographies: Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh by Jyotsna Kamat. Cited by University of California Berkeley Library on South Asian History

- ↑ Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh by Jyotsna Kamat. Cited by University of California Berkeley Library on South Asian History

- ↑ Bhagat Singh Documents Problems of the Punjab

- ↑ Jyotsna Kamat, Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Bharat Desam Biographies: Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Jyotsna Kamat, Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Jyotsna Kamat, Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Jyotsna Kamat, Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Bhagat Singh Documents: Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt's Demands from the British Government

- ↑ Communist Party of India (Marxist): Bhagat Singh Remains Our Symbol of Revolution Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Shahid Bhagat Singh: Jail Note Book of Shahid Bhagat Singh Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Shahid Bhagat Singh: Bhagat Singh quotes from his jail note book

- ↑ CPIM: Bhagat Singh Memorial Day Observed Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ The Tribune India: Excerpts out of Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ CPIM: Bhagat Singh Memorial Day Observed Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Why I am an Atheist: Bhagat Singh 1931.marxists.org. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Tribune India What if Bhagat Singh had lived

- ↑ Bhagat Singh Documents Leaflet thrown in the Central Assembly Hall, New Delhi. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Bharat Desam Biographies: Bhagat Singh bharatadesam.com. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Frontline 18 (8) (Apr. 14 - 27, 2001), Frontline: Paresh R. Vaidya, Of Means and Ends. hinduonnet.com.

- ↑ The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002 film)

- ↑ M. K. Gandhi. The Collected works of Mahatma Gandhi. I - XC, 1884 - 1948. (Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 1979), vol. 45, 359-361.

- ↑ Frontline: Paresh R. Vaidya, Of Means and Ends. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ .Frontline: Paresh R. Vaidya, Of Means and Ends. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ The Sunday Tribune Was Bhagat Singh shot dead? Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Communist Party of India 25th January 2006, letter to Manmohan Singh cpindia.org. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ The Tribune Chandigarh In memory of Bhagat Singh

- ↑ Daily times Pakistan: "Memorial will be built to Bhagat Singh, says governor" Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Punjabi Lok Sukhdev's letter to Gandhi punjabilok.com. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Tribune India: What if Bhagat Singh had lived. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gandhi, M.K. The Collected works of Mahatma Gandhi. I - XC, 1884 - 1948. Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 1979. OCLC 85966948

- Pinney, Christop. Bhagat Singh. Routledge India, 2008. ISBN 978-0415446082

- Sanyal, Jatinder Nath, Bhagat Singh, Kripal Chandra Yadav, and Babar Singh. Bhagat Singh A Biography. (Shahid-i-azam series, vol. 3.) Gurgaon: Hope India, 2006. ISBN 978-8178710594

- Singh, Bhagat, and M. M. Juneja. Selected Collections on Bhagat Singh. Hissar: Modern Publishers, 2007. OCLC 156902585

External links

All links retrieved October 1, 2023.

| Indian Independence Movement | |

|---|---|

| History: | Colonisation - British East India Company - Plassey - Buxar - British India - French India - Portuguese India - More... |

| Philosophies: | Indian nationalism - Swaraj - Gandhism - Satyagraha - Hindu nationalism - Indian Muslim nationalism - Swadeshi - Socialism |

| Events and movements: | Rebellion of 1857 - Partition of Bengal - Revolutionaries - Ghadar Conspiracy - Champaran and Kheda - Jallianwala Bagh Massacre - Non-Cooperation - Flag Satyagraha - Bardoli - 1928 Protests - Nehru Report - Purna Swaraj - Salt Satyagraha - Act of 1935 - Legion Freies Indien - Cripps' mission - Quit India - Indian National Army - Bombay Mutiny |

| Organisations: | Indian National Congress - Ghadar - Home Rule - Khudai Khidmatgar - Swaraj Party - Anushilan Samiti - Azad Hind - More... |

| Indian leaders: | Mangal Pandey - Rani of Jhansi - Bal Gangadhar Tilak - Gopal Krishna Gokhale - Lala Lajpat Rai - Bipin Chandra Pal - Mahatma Gandhi - M. Ali Jinnah - Sardar Patel - Subhash Chandra Bose - Badshah Khan - Jawaharlal Nehru - Maulana Azad - Chandrasekhar Azad - Rajaji - Bhagat Singh - Sarojini Naidu - Purushottam Das Tandon - Tanguturi Prakasam - Alluri Sitaramaraju - More... |

| British Raj: | Robert Clive - James Outram - Dalhousie - Irwin - Linlithgow - Wavell - Stafford Cripps - Mountbatten - More... |

| Independence: | Cabinet Mission - Indian Independence Act - Partition of India - Political integration - Constitution - Republic of India |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.