Lascaux

Discovered in 1940, Lascaux is a series of caves in southwestern France (near Montignac) that is famous for the numerous Paleolithic cave paintings contained on its walls. In 1979, the caves at Lascaux were designated a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) World Heritage site, along with 147 prehistoric sites and 24 painted caves located in the Vézère Valley.

Due to concerns over deterioration of the paintings, the caves were closed to the public, and only qualified researchers were given permission to enter. A replica was constructed to allow visitors to experience and appreciate these magnificent Stone Age artworks, which link us to our ancestors of long ago, without endangering the original paintings.

History

The Lascaux caves were discovered by chance on September 12, 1940 by seventeen year-old Marcel Ravidat, accompanied by three of his friends: Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas. Word traveled quickly, and it was not long before leading archaeologists were contacted. Abbé Henri Breuil, a prominent archaeologist, was one of the first to study the site, where he found bone fragments, oil lamps, and other artifacts, as well as the hundreds of paintings and engraved images.

There was a great deal of public interest in the paintings at Lascaux, and the caves drew a great number of visitors. Included among those fascinated by the art of "primitive" human beings was Pablo Picasso. To his amazement, however, the paintings produced thousands of years ago were not primitive in comparison to contemporary art. On leaving the cave he is said to have exclaimed "We have learned nothing in twelve thousand years."[1]

After World War II, the site entrance was enlarged and the floors lowered to accommodate the nearly 1,200 tourists per day who came to see the art of Paleolithic man. By 1955, the paintings had begun to show signs of deterioration due to the amount of carbon dioxide exhaled by visitors as well as moisture and other environmental changes that occurred when the caves were opened, and so the site was closed to the public in 1963. The paintings were restored, and are now monitored with state of the art technology. Unfortunately, though, fungi, molds, and bacteria have entered the caves and threaten to destroy the paintings and engravings.[2]

Soon after the caves were closed to the public, construction was begun on a painstakingly exact replica of a portion of the caves, located only 200 meters from the original caves. Called "Lascaux II," the replica opened in 1983. Copied down to the texture of the rock, this nearly identical replica allows a large number of people to experience the cave paintings without posing a threat to their longevity. Exact replicas of individual paintings are also displayed in the nearby Center of Prehistoric Art at Thot.

Inside the Caves of Lascaux

The Lascaux caves contain nearly 2,000 painted and engraved figures. There are animals, human figures, and abstract signs. Notably, though, there are no images of landscapes or vegetation.

The Great Hall of the Bulls

Upon entering the caves, there is an initial steep slope, after which one comes into the Hall of the Bulls. The walls of this larger rotunda are covered with paintings of stags, bulls, and horses. Except for a small group of ochre stags, three red bovines, and four red horses, the figures are all painted in black.

The first image in the Hall of the Bulls is that of "the Unicorn," named because of the way the two horns in profile view appear almost to be one large horn, like the mythical unicorn. In front of the "unicorn" is a herd of horses and an incompletely drawn bull. Three large aurochs, an extinct type of wild ox, can be found on the opposite side of the chamber. Most drawings in the Hall of the Bulls consist of pictorial representations of animals; there is no representation of foliage or landscape, and the only symbols present are groupings of black dots and variously colored dashes.

The Painted Gallery

Considered by some to be the pinnacle of Paleolithic cave art, the Painted Gallery is a continuation of the Great Hall of the Bulls.[3] The walls of the Painted Gallery depict numerous horses, aurochs, ibexes, as well as a stag at the entrance to the gallery and a bison at the back.

The Lateral Passage

Branching off to the right of the Great Hall of the Bulls is the Lateral Passage, which connects the Great Hall of the Bulls to the rest of the chambers. The ceiling in this passage is fairly low, even after excavation of the floor after World War II. The walls in this area have deteriorated due to corrosion predating the site's discovery, leaving few paintings or engravings readily visible. It is thought that paintings and engravings once covered the entire surface of this gallery as well as the other galleries.[4]

The Chamber of Engravings

Off the right of the Lateral Passage is the Chamber of Engravings, a smaller rotunda filled with over 600 engravings and paintings. The engravings predominate, and are separated into three sections. On the lower third of the walls are aurochs, above them are deer, and covering the entire dome are horses. There is more overlapping of figures here than in any other chamber, making it difficult to accurately make out the various figures.

The Shaft of the Dead Man

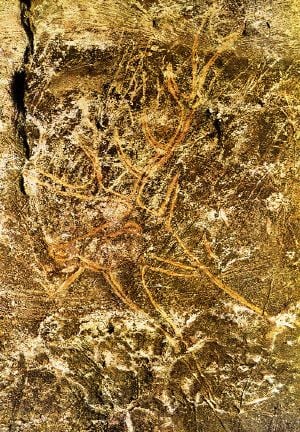

Several meters lower than the back of the Chamber of Engravings is the Shaft of the Dead Man. Here is found the only figure of a human being on the walls of Lascaux. This painting, entitled "Scene of the Dead Man," is a triptych of a bison, a man, and what appears to be a rhinoceros. The man appears to have had a confrontation with the bison, and is pictured lying prone on the ground with a broken spear next to him. To the left of the spear lies what looks like a stick with a bird on the top, a fact made more significant by the observation that the man also appears to have a bird-shaped head. Also present is the hook sign, which may represent a spear thrower.

The Main Gallery

Off to the left of the Chamber of Engravings is the Main Gallery, a series of chambers that descend in size. Within these chambers are several panels, mostly found on the left wall, and each having distinct characteristics. "The Panel of the Imprint," for example, contains horses, bison, and square symbols, while the "Black Cow Panel" has a single black cow with seven ibexes. Some of the square symbols are polychromatic, using shades of yellow, red, and violets to divide the larger square into smaller squares. In the rear of the Main Gallery, the Panel of the Back-to-Back Bison is the most typical example of three dimensional perspective. One bison overlaps the other, and reserves (small areas left blank) surround the rear bison as well as the back limbs of each animal. The three dimensional effect is heightened by the fact that the painting is situated in an area where the rock wall curves out on either side. On the right wall there is only one group of stags, named the "Swimming Stags." Only the heads and shoulders of the stags are visible.

The Chamber of Felines

Past the Main Gallery, deep in the cave, is the Chamber of Felines. Here, as in the other chambers, are horses and bison, but unlike other areas, there are felines, as well as an absence of aurochs. This chamber is similar to the Chamber of Engravings in that it contains more engravings than paintings. The figures in this chamber have been poorly preserved, and are sometimes difficult to make out. At the end of the chamber is a group of three sets of two red dots, which may suggest a means of marking the end of the sanctuary.

Technique and Purpose

The cave painters at Lascaux, like those of other sites, used naturally occurring pigments to create their paintings. They may have used brushes, though none were found at the site, but it is equally as likely that they used mats of moss or hair, or simply chunks of raw color. Some parts of the paintings were painted with an airbrushing technique; hollow bones stained with color have been found in the caves. Since the caves have no natural light, torches and stone lamps filled with animal fat were used to illuminate the caves.

Research places most of the paintings around 15,000 B.C.E., although the subject matter and style of certain figures suggests that they may be somewhat more recent, perhaps only 10,000 B.C.E.[4] Thus, although containing some of the most famous Paleolithic artworks in the world, Lascaux does not contain the oldest; the Chauvet Cave discovered in 1994 in the Ardèche region of southern France contains paintings dating back as far as 32,000 B.C.E.

The true purpose of the images found in all these caves is a matter of debate. Due to the inaccessibility of many of the chambers and the size and grandeur of the paintings at Lascaux, many believe that the caves served as sacred spaces or ceremonial meeting places.[5] Animals may have been drawn in order to ensure a successful hunt, or they may have been drawn afterwards to provide a resting place for the spirits of the slain animals—a practice that would point to an animistic religion. Others argue that the cave paintings were nothing more than a type of graffiti drawn by adolescent boys, a theory partially supported by the measurements of hand prints and footprints found in Paleolithic caves.[6]

The "Shaft of the Dead Man" has also sparked numerous theories as to its purpose. Some believe that the bird-like head of the man is evidence of shamanism, and that the caves may have served to facilitate trance-like states (particularly if the caves contained high levels of carbon dioxide). Others argue that the painting is narrative, and describes an event that took place in life or in a dream.

As for the true meaning of the paintings, the number, style, and location of paintings (both in Lascaux and other nearby sites) have led most experts to believe that the images served some sort of spiritual or ceremonial purpose. It is also possible that more than one theory has validity; for example, adolescent boys may have added their marks to the painted walls made by adults in preparation for the hunt. Whatever their original purpose may have been, cave paintings now serve as a priceless link between modern and Paleolithic man.

Notes

- ↑ Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists (Anchor, 2007, ISBN 1400078873).

- ↑ International Committee for the Preservation of Lascaux, Famous World Heritage Site in Peril. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ↑ The Lascaux Caves Sacred Destinations. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Cave of Lascaux. French Ministry of Culture and Communication. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ 2000. Lascaux ca. 15,000 B.C.E. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ William H. McNeill, Secrets of the Cave Paintings. The New York Review of Books, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aujoulat, Norbert. Lascaux: Movement, Space and Time. Harry N. Abrams Pub., 2005. ISBN 0810959003

- Aujoulat, Norbert. The Splendour of Lascaux. Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2005. ISBN 0500051356

- Curtis, Gregory. The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. Anchor, 2007. ISBN 1400078873

- Ruspoli, Mario. The Cave of Lascaux. Harry N. Abrams Pub., 1987. ISBN 0810912678

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- The Dawn of Prehistoric Rock Art An article summarizing the earliest known rock art, with a focus on recently discovered painted caves in Europe, Grotto Cosquer and Grotto Chauvet.

- Lascaux Cave — Saving Beauty Notes on damage inflicted on the cave

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.