Unicorn

The unicorn, a legendary creature usually depicted with the body of a horse, but with a single—usually spiral—horn growing out of its forehead, is one of the most revered mythical beasts of all time. Appearing in numerous cultures, the unicorn has come to be a symbol of purity and beauty, and is one of the few mythical creatures not associated with violence, danger, and fear. As humans advance, establishing a world of peace and harmony, these characteristics of the unicorn will come to be manifested through human beings.

Overview

The unicorn usually has the body of a horse, with a single (usually spiral) horn growing out of its forehead (hence its name—cornus being Latin for “horn”). In the West, the image of the unicorn has a billy-goat beard, a lion's tail, and cloven hooves, which distinguish it from a horse. In the East, the unicorn is depicted somewhat differently. Though the qilin (麒麟, Chinese), a creature in Chinese mythology, is sometimes called "the Chinese unicorn," it is a hybrid animal that looks less unicorn than chimera, with the body of a deer, the head of a lion, green scales, and a long forwardly-curved horn. The Japanese Kirin, though based on the Chinese animal, is usually portrayed as more closely resembling the Western unicorn than the Chinese qilin.[1] The name Kirin is also used in Japanese for giraffe.

In both the East and West, the unicorn is a symbol of purity. In medieval lore, the alicorn, the spiraled horn of the unicorn (the word "Alicorn" can also be the name for a winged unicorn/horned Pegasus), is said to be able to heal and neutralize poisons. This virtue is derived from Ctesias' reports on the unicorn in India, that it was used by the rulers of that place to make drinking cups that would detoxify poisons.

Origins

Unlike most other legendary creatures, the unicorn was and, still is by some, believed to have been a real animal in the past. This may be due to the fact that physiologically, the unicorn is similar to animals that live in large groups in the wild and have regularly been hunted and revered by humans, such as deer, horses, oryx, and elands.

Based on carvings found on seals of an animal that resembles a bull (and which may in fact be a simplistic way of depicting a bull in profile), it has been claimed that the unicorn was a common symbol during the Indus Valley Civilization, appearing on many seals. It may have symbolized a powerful social group. Other extinct creatures, such as the Elasmotheium, an extinct relative of the rhinoceros that lived in the European steppe area shares many similar physical characteristics with the unicorn, as does the narwhal, which, while a sea animal, has the only type of horn in nature that compares to that of the unicorn. Some scientists have even speculated that perhaps a mutant form of a goat was mistaken for a unicorn in the past.

The narwhal

The unicorn horns often found in cabinets of curiosities and other contexts in medieval and Renaissance Europe were very often examples of the distinctive straight spiral single tusk of the narwhal, an Arctic cetacean (Monodon monoceros), as Danish zoologist Ole Worm established in 1638.[2] They were brought south as a very valuable trade, passing the various tests intended to spot fake unicorn horns. The usual depiction of the unicorn horn in art derives from these.

Compounding the question of the unicorn's origin are the various allegations of authentic remains. A unicorn skeleton was supposedly found at Einhornhöhle ("Unicorn Cave") in Germany's Harz Mountains in 1663. Claims that the so-called unicorn had only two legs (and was constructed from fossil bones of mammoths and other animals) are contradicted or explained by accounts that souvenir-seekers plundered the skeleton; these accounts further claim that, perhaps remarkably, the souvenir-hunters left the skull, with horn. The skeleton was examined by Leibniz, who had previously doubted the existence of the unicorn, but was convinced thereby.

Stories of the unicorn stretch back to ancient Greece from such sources as Herodotus, Aristotle, and Ctesias, although there seems to be little consistency between the three as to geographical location and whether the animal possessed magical powers.[3] The unicorn appears in ancient Sumerian culture, as well as throughout the Old Testament of the Bible. It is likely that these renditions all come from regional folklore and natural history.

The origins of the unicorn in the East are a little different. The qilin of China is not similar in physicality to any naturally existing animal, and its significance in legends of justice and prophecy suggest that it is a completely fictitious creature. This does not mean however, that the ancient Chinese did not believe in its existence. Nor did ancient Indians who held onto the myth that a unicorn had saved India from invasion by Genghis Khan.[4]

Cultural Depictions

In Mesopotamian and Sumerian artwork and the Bible, the unicorn is depicted as a symbol of strength and virtue. In 200 C.E., Tertullian had called the unicorn a small fierce kidlike animal, and a symbol of Christ. Ambrose, Jerome, and Basil agreed. However, it was not until the medieval era that the unicorn myth grew into a literary staple and cultural icon.

The predecessor of the medieval bestiary, compiled in Late Antiquity and known as Physiologus, popularized an elaborate allegory in which a unicorn, trapped by a maiden (representing the Virgin Mary) stood for the Incarnation. As soon as the unicorn sees her, it lays its head on her lap and falls asleep. This became a basic emblematic tag that underlies medieval notions of the unicorn, justifying its appearance in every form of religious art.

The unicorn also figured in courtly terms: for some thirteenth-century French authors such as Thibaut of Champagne and Richard of Fournival, the lover is attracted to his lady as the unicorn is to the virgin. This courtly version of salvation provided an alternative to God's love and was assailed as heretical. With the rise of humanism, the unicorn also acquired more orthodox secular meanings, emblematic of chaste love and faithful marriage. It plays this role in Petrarch's Triumph of Chastity.[5]

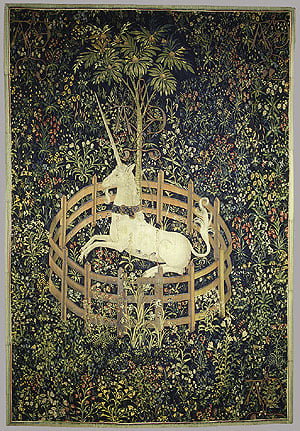

The Hunt of the Unicorn

One traditional artifact of the unicorn is the hunting of the animal involving entrapment by a virgin. The famous late Gothic series of seven tapestry hangings, The Hunt of the Unicorn, is a high point in European tapestry manufacture, combining both secular and religious themes. The tapestries now hang in the Cloisters division of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In the series, richly dressed noblemen, accompanied by huntsmen and hounds, pursue a unicorn against millefleurs backgrounds or settings of buildings and gardens. They bring the animal to bay with the help of a maiden who traps it with her charms, appear to kill it, and bring it back to a castle; in the last and most famous panel, “The Unicorn in Captivity,” the unicorn is shown alive again and happy, chained to a pomegranate tree surrounded by a fence, in a field of flowers. Scholars conjecture that the red stains on its flanks are not blood but rather the juice from pomegranates, which were a symbol of fertility. However, the true meaning of the mysterious resurrected unicorn in the last panel is unclear. The series was woven about 1500 in the Low Countries, probably Brussels or Liège, for an unknown patron.

A set of six tapestries called the Dame à la licorne (Lady with the unicorn) at the Musée de Cluny, Paris, woven in the Southern Netherlands about the same time, pictures the five senses, the gateways to temptation, and finally Love ("A mon seul desir" the legend reads), with unicorns featured in each hanging. Facsimiles of the unicorn tapestries are being woven for permanent display in Stirling Castle, Scotland, to take the place of a set recorded in the castle in the sixteenth century.

Heraldry

In heraldry, a unicorn is depicted as a horse with a goat's cloven hooves and beard, a lion's tail, and a slender, spiral horn on its forehead. Whether because it was an emblem of the Incarnation or of the fearsome animal passions of raw nature, the unicorn was not widely used in early heraldry, but became popular from the fifteenth century. Though sometimes shown collared, which may perhaps be taken in some cases as an indication that it has been tamed or tempered, it is more usually shown collared with a broken chain attached, showing that it has broken free from its bondage and cannot be taken again.

It is probably best known from the royal arms of Scotland and the United Kingdom: two unicorns support the Scottish arms; a lion and a unicorn support the UK arms. The arms of the Society of Apothecaries in London has two golden unicorn supporters.

Notes

- ↑ Kevin Owens, Unicorn Legends All About Unicorns. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ Unicorn Ocultopedia. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ Hillary Smith,The Unicorn Myth World History Encyclopedia (October 23, 2020). Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ Geoffrey Humble, Chinggis Khan versus the Unicorn History Today 66(4) (April 2016). Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ Triumph of Chastity The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beer, Rüdiger Robert. Unicorn: Myth and Reality. Mason/Charter, 1977. ISBN 0884055833

- Gotfredsen, Lise. The Unicorn. Abbeville Press, 1999. ISBN 0789205955

- Johnsgard, Paul, and Karin Johnsgard. Dragons and Unicorns: A Natural History. St. Martin's Griffin, 1992. ISBN 0312084994

- Nigg, Joe. Wonder Beasts: Tales and Lore of the Phoenix, the Griffin, the Unicorn, and the Dragon. Libraries Unlimited, 1995. ISBN 156308242X

- Shepard, Odell. The Lore of the Unicorn. Dover Publications, 2012. ISBN 0486278034

External links

All links retrieved November 8, 2023.

- Facts about Scotland’s national animal the Unicorn By Lindsey Johnstone, The Scotsman, May 6, 2014.

- Unicorns, West and East American Museum of Natural History.

- The unicorn – Scotland’s national animal by James Walsh National Trust for Scotland.

- Where did the unicorn myth come from? By Patrick Pester, Live Science, April 9, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.