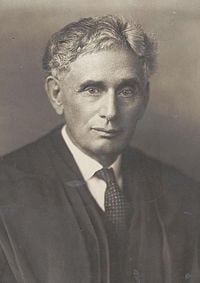

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American litigator, United States Supreme Court Justice, advocate of privacy, and known as the "People's Attorney" for his populist ideas. He developed the Brandeis Brief, which forever changed the operation of the Supreme Court, bringing data and arguments from the social sciences into consideration in determining the law. His work on the Supreme Court, often aligned with colleague Oliver Wendell Holmes involved dissent from the majority, his views foreshadowing decisions made in later courts. He was a staunch supporter of Roosevelt's New Deal programs when the majority opposed them. Brandeis was also active in and a leader of the American Zionist movement, arguing that the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine was compatible with American patriotism. His legacy is found in the institutions and awards named after him, but more importantly in the efforts he made to safeguard civil rights, such as freedom of speech, and privacy, including the right to hold beliefs, thoughts, emotions, and other non-material, and therefore most essential and valued, aspects of our lives without interference and control by government or other authority.

Life

Louis Dembitz Brandeis was born on November 13, 1856 in Louisville, Kentucky. His family, Bohemian Jews, had immigrated to the United States from Prague following the failed revolution of 1848. Louis graduated from high school at age 14 with the highest honors.

In 1872, he went to Europe, first to travel with his family, and then for two years of school at Dresden. Returning in 1875, Brandeis entered Harvard University, graduating from its law school in 1877, not only at the head of his class but with the highest scores of any student to have attended Harvard Law School.

After practicing law for a short time in St. Louis, Missouri, Brandeis became an attorney in Boston, founding, with his Harvard Law School classmate Samuel D. Warren, the prominent Boston law firm now known as Nutter, McClennen and Fish. The firm was successful, garnering Brandeis financial security and allowing him to take an active role in progressive causes.

He married and bought a house on Village Avenue in Dedham, Massachusetts. The house was near Dedham Square and the courthouse where Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were tried. During the trial Brandeis welcomed Sacco's wife and children into his home.

Brandeis was a member of the Dedham Country and Polo Club and the Dedham Historical Society, as well as a member of the Society in Dedham for Apprehending Horse Thieves.[1][2] He wrote to his brother of the town, "Dedham is a spring of eternal youth for me. I feel newly made and ready to deny the existence of these grey hairs."[3]

Louis Brandeis died in 1941. His cremated remains are interred under the portico of the Louis Brandeis Law school at the University of Louisville. A large collection of Brandeis' personal and official files is also archived at that institution.

Work

After graduating from Harvard Law School, Brandeis moved to St. Louis to practice law, returning to Boston after a year to work in a private practice. He also worked as an unpaid counsel for the New England Policy-Holders' Protective Committee to try to remedy abuses by life insurance companies.

Brandeis argued cases in favor of having a maximum number of work hours in a week, in favor of minimum wage, and against monopolies. His work in the last field was integral to the development of the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act. He became known as the "People's Attorney" for his populist ideas and representation of the interests of the workers.

Brandeis was appointed by Woodrow Wilson to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1916 (sworn-in on June 5), and served until 1939. Many were surprised that Wilson—son of a Christian minister—would appoint to the highest court in the land the very first Jewish Supreme Court Justice. However, Brandeis had for some years been a contributor to the progressive wing of the United States Democratic Party, and had published a noted book in support of competition rather than monopoly in business. President Wilson, who believed deeply that government must be a moral force for good, responded to similar sentiments in the thought and writings of Brandeis.

The Brandeis Brief

Brandeis worked alongside women's rights activists Florence Kelley and Josephine Clara Goldmark to improve working conditions for women. In what became known as the "Brandeis Brief," he submitted a legal brief in the 1908 Supreme Court case Muller v. Oregon, containing sociological information on the issue of the impact of long working hours on women. The Brandeis Brief was a 113 page document with statistical data, laws, journal articles, and other material. This was the first instance in the United States that social science had been used in law, and it changed the direction of the Supreme Court and of U.S. law. The Brandeis Brief became the model for future Supreme Court presentations as they would continue to consider economics, sociology, history, and expert opinions.

Supreme Court Justice

Overcoming significant opposition to his appointment, notably from ex-President and future Chief Justice William Howard Taft and Harvard University president A. Lawrence Lowell who submitted a petition signed by Lowell and "fifty-four citizens of Boston, most of whom are understood to be lawyers," which read in part

An appointment to this court should only be conferred upon a member of the legal profession whose general reputation is as good as his legal attainments are great. We do not believe that Mr. Brandeis has the judicial temperament and capacity which should be required in a Judge of the Supreme Court. His reputation as a lawyer is such that he has not the confidence of the people.[4]

Brandeis was confirmed to the Supreme Court on June 1, 1916, on a largely party-line 47-22 vote, with one Democrat opposed and three Republicans in favor.[5] Brandeis learned of his confirmation when he rode the train home from his office in Boston to his house in Dedham that night and his wife greeted him as "Mr. Justice."[6] He would become one of the most influential and respected Supreme Court Justices in United States history. His votes and opinions envisioned the greater protections for individual rights and greater flexibility for government in economic regulation that would prevail in later courts.

In his widely-cited dissenting opinion in Olmstead v. United States (1928), Brandeis argued, as he had in an influential law review article prior to being nominated to the Court, that the Constitution protected a "right of privacy," calling it "the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men." Brandeis' position in Olmstead eventually became law in 1967 with Katz v. United States, which overturned the Olmstead decision.

Brandeis also joined with fellow justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in calling for greater Constitutional protection for speech, disagreeing with the Court's analysis in upholding a conviction for aiding the Communist Party in Whitney v. California (1927) (though concurring with the disposition of the case on technical grounds). Brandeis' opinion foreshadowed the greater speech protections enforced by the Earl Warren Court.

Brandeis also opposed the Supreme Court's doctrine of "liberty of contract," which often acted to shield business from government regulation on the right of employers and employees to freely contract with each other, and argued that the Court should adopt a broader view of what constituted "commerce" which could be regulated by Congress, foreshadowing decisions such as the 1941 United States v. Darby.

During the 1932-1937 Supreme Court terms, Brandeis, along with Justices Cardozo and Stone, was a member of the "Three Musketeers," considered to be the liberal faction of the Supreme Court. The three were highly supportive of President Roosevelt's New Deal programs, which most of the other Supreme Court Justices opposed. In New State Ice Co. v. Leibmann (1932), Brandeis in dissent famously urged that the states should be able to be "laboratories" for innovative government action, in the face of the Supreme Court's frequent invalidation of state measures regulating business. Brandeis' views on "liberty of contract" would prevail in the long run, culminating in the seminal Supreme Court case of West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). He urged deference to legislative judgments when fundamental individual liberties are not seriously threatened, showing a healthy respect for the vertical (federal vs. state vs. individual) and horizontal (judicial vs. legislative) separations of power.

As an octogenarian, Brandeis was deeply offended by his friend Roosevelt's court-packing scheme of 1937, with its implication that elderly justices needed special help to carry out their duties. Brandeis retired from the Court in 1939, to be replaced by William O. Douglas.

Zionist leader

Brandeis was also a prominent American Zionist. Not raised religious, Brandeis became involved in Zionism (the movement to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine) through a 1912 conversation with Jacob de Haas, editor of a Boston Jewish weekly and a follower of Theodore Herzl. As a result, Brandeis became active in the Federation of American Zionists. With the outbreak of World War I, the Zionist movement's headquarters in Berlin became ineffectual, and American Jewry had to assume larger responsibility for the Zionist movement. When the Provisional Executive Committee for Zionist Affairs was established in New York City, Brandeis accepted unanimous election to be its head, and from 1914 to 1918 he was the leader of American Zionism. He embarked on a speaking tour in the fall and winter of 1914-1915 to support the Zionist cause. Brandeis emphasized the goal of self-determination and freedom for Jews through the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and the compatibility of Zionism and American patriotism.

Brandeis brought his influence in the Woodrow Wilson administration to bear in the negotiations leading up to the Balfour Declaration. Brandeis split with the European branch of Zionism, led by Chaim Weizmann, and resigned his leadership role in 1921. He retained membership, however, and remained active in Zionism until the end of his life.

Legacy

Louis D. Brandeis remains influential both for who he was and what he did. His appointment as the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice was a landmark move in a country that had long suffered from anti-Semitism. Not content to rest on this achievement, Brandeis went on to contribute landmark opinions while sitting on the Supreme Court. The foundations laid by Brandeis and those in the Zionist movement were instrumental in the creation of the state of Israel following World War II.

A number of institutions have honored Brandeis' legacy by taking his name. Brandeis University, a liberal arts university located in Waltham, Massachusetts is named after him. Several Brandeis Awards are named in his honor. A collection of his personal papers is available at the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis University. The University of Louisville's Louis D. Brandeis School of Law is also named after him. The remains of both Justice Brandeis and his wife are interred beneath the school; with his remains appropriately located approximately 50 yards from Rodin's The Thinker. His professional papers are archived at the library there. The school's principal law review publication, the Brandeis Law Journal, is likewise named in his honor. The law school's Louis D. Brandeis Society awards the Brandeis Medal. One of the buildings of Hillman Housing Corporation, a housing cooperative founded by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, in the Lower East Side of Manhattan is named after him. A New York City Public High school, "Louis D. Brandeis High School," is named after the justice. Finally, Kibbutz Ein Hashofet (hebrew: עין השופט) in Israel (founded 1937) is named after him—"Ein Hashofet" meaning literally "Spring of the Judge," the name chosen due to Brandeis' Zionism.

Selected quotations

- "Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears."[7]

- "Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman." [8]

- "Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty."[9]

- "Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the state was to make men free to develop their faculties, and that in its government the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government."[10]

- "Full and free exercise of this right by the citizen is ordinarily also his duty; for its exercise is more important to the nation than it is to himself. Like the course of the heavenly bodies, harmony in national life is a resultant of the struggle between contending forces. In frank expression of conflicting opinion lies the greatest promise of wisdom in governmental action; and in suppression lies ordinarily the greatest peril."[11]

- "The makers of our Constitution undertook to secure conditions favorable to the pursuit of happiness. They recognized the significance of man's spiritual nature, of his feelings and of his intellect. They knew that only a part of the pain, pleasure and satisfactions of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone-the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men."[12]

- "Decency, security, and liberty alike demand that government officials shall be subjected to the same rules of conduct that are commands to the citizen. In a government of laws, existence of the government will be imperiled if it fails to observe the law scrupulously. Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. Crime is contagious. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law; it invites every man to become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy."[13]

- "There are many men now living who were in the habit of using the age-old expression: 'It is as impossible as flying'. The discoveries in physical science, the triumphs in invention, attest the value of the process of trial and error. In large measure, these advances have been due to experimentation."[14]

Major Works

Selected works

- The Brandeis Guide to the Modern World, Alfred Lief, editor (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1941)

- Brandeis on Zionism, Solomon Goldman, editor (Washington, D.C.: Zionist Organization of America, 1942)

- Business, a Profession, Ernest Poole, editor (Boston, MA: Small, Maynard, 1914)

- The Curse of Bigness, Osmond K. Fraenkel, editor (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1934)

- The Words of Justice Brandeis, Solomon Goldman, editor (New York, N.Y.: Henry Schuman, 1953)

- Others People's Money—and How the Bankers Use It (New York, NY: Stokes, 1914)

- Melvin I. Urofsky & David W. Levy, editors, Half Brother, Half Son: The Letters of Louis D. Brandeis to Felix Frankfurter (University of Oklahoma Press, 1991)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, editor, Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (State University of New York Press, 1980)

- Melvin I. Urofsky & David W. Levy, editors, Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (State University of New York Press, 1971-1978, 5 vols.)

- Louis Brandeis & Samuel Warren "The Right to Privacy," 4 Harvard Law Review 193-220 (1890-91)

- "The Living Law," 10 Illinois Law Review 461 (1916)

Selected opinions

- Sugarman v. United States (1919) (majority) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920) (dissenting) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Whitney v. California (1927) (concurring) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Ruthenberg v. Michigan (1927) (unpublished dissent) Retrieved May 7,

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann (1932) (dissenting) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority (1936) (concurring) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938) (majority) Retrieved May 7, 2007.

Notes

- ↑ Dedham Historical Society Newsletter Dedham Historical Society. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Bob Hanson. Historical Sketch (html). The Society in Dedham for Apprehending Horse Thieves. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ↑ Dedham Historical Society Newsletter Dedham Historical Society. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Contends Brandeis Is Unfit; Dr Lowell and 54 Bostonians Submit Petition to Senate." The New York Times, February 13, 1916, 50.

- ↑ "Confirm Brandeis by Vote of 47 to 22," The New York Times, June 2, 1916.

- ↑ Dedham Historical Society Newsletter Dedham Historical Society. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Whitney v. California (1927) (concurring) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Louis D. Brandeis, 1914, Other People’s Money, and How the Bankers Use It, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 9780312122577

- ↑ Whitney v. California (1927) (concurring) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Whitney v. California (1927) (concurring) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920) (dissenting) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ Olmstead v. U.S. (1928) (dissenting) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ Olmstead v. U.S. (1928) (dissenting) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann (1932) (dissenting) American Library Association. Retrieved May 6, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Leonard. 1984. Brandeis & Frankfurter: A Dual Biography. New York, NY: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060152451

- Burt, Robert A. 1988. Two Jewish Justices: Outcasts in the Promised Land. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520067495

- Levy, David W. (ed.). 2002. The Family Letters of Louis D. Brandeis. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806134046

- Mersky, Ray M. 1958. Louis Dembitz Brandeis 1856-1941: Bibliography. Fred B Rothman & Co; reprint ed. ISBN 0837724376

- Paper, Lewis J. 1983. An Intimate Biography of one of America's Truly Great Supreme Court Justices. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Pretice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 080650966X

- Peare, Catherine Owens. 1970. The Louis D. Brandeis Story. Ty Crowell Co. ISBN 0690511175

- Strum, Philippa. 1988. Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0805208844

- Urofsky, Melvin I. 1981. Louis D. Brandeis & the Progressive Tradition. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co. ISBN 0316887889

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.