Malwa (Madhya Pradesh)

- "Malwa" redirects here.

| Malwa | |

| Largest city | Indore |

| Main languages | Malvi, Hindi |

| Area | 81,767 km² |

| Population (2001) | 18,889,000 |

| Density | 231/km² |

| Birth rate (2001) | 31.6 |

| Death rate (2001) | 10.3 |

| Infant mortality rate (2001) | 93.8 |

Malwa (Malvi:माळवा, IAST: Māļavā), a region in west-central northern India, occupies a plateau of volcanic origin in the western part of Madhya Pradesh state. That region had been a separate political unit from the time of the Aryan tribe of Malavas until 1947, when the British Malwa Agency merged into Madhya Bharat. Although political borders have fluctuated throughout history, the region has developed its own distinct culture and language.

Malwa has experienced wave after wave of empires and dynasties ruling the region. With roots in the Neolithic period, Malwa established one of the first powerful empires in the region, Avanti. Rooted in the founding of Hindu philosophy and religion, Avanti became a key region for the establishment of Hinduism. Jainism and Buddhism appeared as well. In the 1200s, Islam appeared, establishing a mighty kingdom in the region. Development of arts and science, as well as mathematics and astronomy, have been a hallmark of the region. Malwa has earned fame for its standing as a world leader in the legal production and distribution of opium.

Overview

The plateau that forms a large part of the region carries the name Malwa Plateau, after the region. The average elevation of the Malwa plateau sits at 500 metres, and the landscape generally slopes towards the north. The Chambal River and its tributaries drains most of the region; the upper reaches of the Mahi River drains the western part. Ujjain served as the political, economic, and cultural capital of the region in ancient times, Indore, presently the largest city and commercial center. The majority of people in Malwa work in agriculture. The region has been one of the important producers of opium in the world. Cotton and soybeans constitute other important cash crops, while textiles represent a major industry.

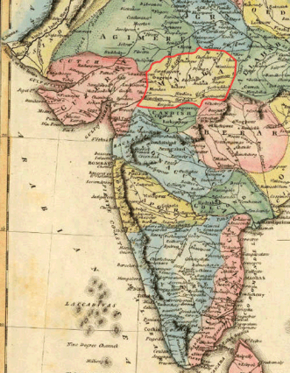

The region includes the Madhya Pradesh districts of Dewas, Dhar, Indore, Jhabua, Mandsaur, Neemuch, Rajgarh, Ratlam, Shajapur, Ujjain, and parts of Guna and Sehore, and the Rajasthan districts of Jhalawar and parts of Banswara and Chittorgarh. Politically and administratively, the definition of Malwa sometimes extends to include the Nimar region south of the Vindhyas. Geologically, the Malwa Plateau generally refers to the volcanic upland south of the Vindhyas, which includes the Malwa region and extends east to include the upper basin of the Betwa and the headwaters of the Dhasan and Ken rivers. The region has a tropical climate with dry deciduous forests that a number of tribes call home, most importantly the Bhils. The culture of the region has had influences from Gujarati, Rajasthani and Marathi cultures. Malvi has been the most commonly used language especially in rural areas, while people in cities commonly understand Hindi. Major places of tourist interest include Ujjain, Mandu, Maheshwar, and Indore.

Avanti represents the first significant kingdom in the region, developing into an important power in western India by around 500 B.C.E., when the Maurya Empire annexed it. The fifth century Gupta period emerged as a golden age in the history of Malwa. The dynasties of the Parmaras, the Malwa sultans, and the Marathas have ruled Malwa at various times. The region has given the world prominent leaders in the arts and sciences, including the poet and dramatist Kalidasa, the author Bhartrihari, the mathematicians and astronomers Varahamihira and Brahmagupta, and the polymath king Bhoj.

History

Several early stone age or lower paleolithic habitations have been excavated in eastern Malwa.[1] The name Malwa derives from the ancient Aryan tribe of Malavas, about whom historians and archeologists know nothing except that they founded the Vikrama Samvat; a calendar dating from 57 B.C.E. widely used in India and popularly associated with the king Chandragupta Vikramaditya. The name Malava derives from the Sanskrit term Malav, and means “part of the abode of Lakshmi”.[2] The location of the Malwa or Moholo, mentioned by the seventh century Chinese traveler Xuanzang, may be identified with present-day Gujarat.[3] Arabic records, such as Kamilu-t Tawarikh by Ibn Asir mention the region as Malibah. [4]

Ujjain, also known historically as Ujjaiyini and Avanti, emerged as the first major center in the Malwa region during India's second wave of urbanisation in the seventh century B.C.E. (the Indus Valley Civilization being the first wave). Around 600 B.C.E. an earthen rampart rose around Ujjain, enclosing a city of considerable size. Avanti emerged as one of the prominent mahajanapadas of the Indo-Aryans. In the post-Mahabharata period (around 500 B.C.E.) Avanti became an important kingdom in western India; ruled by the Haihayas, a people possibly of mixed Indo-Aryan and aboriginal descent responsible for the destruction of Naga power in western India.[5] The Maurya empire conquered the region in the mid-fourth century B.C.E. Ashoka, later a Mauryan emperor, governed Ujjain in his youth. After the death of Ashoka in 232 B.C.E., the Maurya Empire began to collapse. Although little evidence exists, the Kushanas and the Shakas probably ruled the Malwa during the 2nd century B.C.E. and first century B.C.E. The Western Kshatrapas and the Satavahanas disputed ownership of the region during the first three centuries C.E. Ujjain emerged a major trading center during the first century C.E.

Malwa became part of the Gupta Empire during the reign of Chandragupta II (375–413), also known as Vikramaditya, who conquered the region, driving out the Western Kshatrapas. The Gupta period has been widely regarded by historians as a golden age in the history of Malwa, when Ujjain served as the empire's western capital. Kalidasa, Aryabhata and Varahamihira all based in Ujjain, which emerged as a major centre of learning, especially in astronomy and mathematics. Around 500, Malwa re-emerged from the dissolving Gupta empire as a separate kingdom; in 528, Yasodharman of Malwa defeated the Hunas, who had invaded India from the north-west. During the seventh century, the region became part of Harsha's empire, and he disputed the region with the Chalukya king Pulakesin II of Badami in the Deccan. In 786, the Rashtrakuta kings of the Deccan captured the region, the Rashtrakutas and the Pratihara kings of Kannauj disputing rule until the early part of the tenth century. From the mid-tenth century, the Paramara clan of Rajputs ruled Malwa, establishing a capital at Dhar. King Bhoj, known as the great polymath philosopher-king of medieval India, ruled from about 1010 to 1060; his extensive writings cover philosophy, poetry, medicine, veterinary science, phonetics, yoga, and archery. Under his rule Malwa became an intellectual centre of India. Bhoj also founded the city of Bhopal to secure the eastern part of his kingdom. His successors ruled until about 1200, when the Delhi Sultanate conquered Malwa.

Dilawar Khan, previously Malwa's governor under the rule of the Delhi sultanate, declared himself sultan of Malwa in 1401 after the Mongol conqueror Timur attacked Delhi, causing the break-up of the sultanate into smaller states. Khan started the Malwa Sultanate and established a capital at Mandu, high in the Vindhya Range overlooking the Narmada River valley. His son and successor, Hoshang Shah (1405–35), beautified Mandu with great works of art and buildings. Hoshang Shah's son, Ghazni Khan, ruled for only a year, succeeded by Sultan Mahmud Khalji (1436–69), the first of the Khalji sultans of Malwa, who expanded the state to include parts of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and the Deccan. The Muslim sultans invited the Rajputs to settle in the country. In the early sixteenth century, the sultan sought the aid of the sultans of Gujarat to counter the growing power of the Rajputs, while the Rajputs sought the support of the Sesodia Rajput kings of Mewar. Gujarat stormed Mandu in 1518 and 1531, and shortly after that, the Malwa sultanate collapsed. The Mughal emperor Akbar captured Malwa in 1562 and made it a province of his empire. By the seventeenth century, Mandu had been abandoned .

As the Mughal state weakened after 1700, the Marathas held sway over Malwa. Malhar Rao Holkar (1694–1766) became leader of Maratha armies in Malwa in 1724, and in 1733 the Maratha Peshwa granted him control of most of the region, formally ceded by the Mughals in 1738. Ranoji Scindia noted Maratha Commander established his head quarters at Ujjain in 1721. Daulatrao Scindia later moved that capital to Gwalior. Another Maratha general, Anand Rao Pawar, established himself as the Raja of Dhar in 1742, and the two Pawar brothers became Rajas of Dewas. At the end of the eighteenth century, Malwa became the venue of fighting between the rival Maratha powers and the headquarters of the Pindaris, who plundered irregularly. The British general Lord Hastings rooted out the Pindaris in a campaign, Sir John Malcolm further establishing order.[3] The Holkar dynasty ruled Malwa from Indore and Maheshwar on the Narmada until 1818, when the British defeated the Marathas in the Third Anglo-Maratha War, and the Holkars of Indore became a princely state of the British Raj. After 1818 the British organized the numerous princely states of central India into the Central India Agency; the Malwa Agency became a division of Central India, with an area of 23,100 km² (8,919 square miles) and a population of 1,054,753 in 1901. It comprised the states of Dewas (senior and junior branch), Jaora, Ratlam, Sitamau and Sailana, together with a large part of Gwalior, parts of Indore and Tonk, and about thirty five small estates and holdings. Political power proceeded from Neemuch.[3] Upon Indian independence in 1947, the Holkars and other princely rulers acceded to India, and most of Malwa became part of the new state of Madhya Bharat, which merged into Madhya Pradesh in 1956.

See also: Rulers of Malwa, History of India

Geography

The Malwa region occupies a plateau in western Madhya Pradesh and south-eastern Rajasthan (between 21°10′N 73°45′E and 25°10′N 79°14′E),[5] with Gujarat in the west. To the south and east stands the Vindhya Range and to the north the Bundelkhand upland. The plateau constitutes an extension of the Deccan Traps, formed between sixty and sixty eight million years ago[6][7] at the end of the Cretaceous period. In that region black, brown and bhatori (stony) soil make up the main classes of soil. The volcanic, clay-like soil of the region owes its black color to the high iron content of the basalt from which it formed. The soil requires less irrigation because of its high capacity for moisture retention. The other two soil types, lighter, have a higher proportion of sand.

The average elevation of the plateau measures 500 m. Some of the peaks over 800 m high include Sigar (881 m), Janapav (854 m) and Ghajari (810 m). The plateau generally slopes towards the north. The Mahi River drains the western part of the region, while the Chambal River drains the central part, and the Betwa River and the headwaters of the Dhasan and Ken rivers drain the east. The Shipra River has historical importance because of the Simhasth mela, held every twelve years. Other notable rivers include Parbati, Gambhir and Choti Kali Sindh. Malwa's elevation gives it a mild, pleasant climate; a cool morning wind, the karaman, and an evening breeze, the Shab-e-Malwa, make the summers less harsh.

The year popularly divides into three seasons: summer, the rains, and winter. Summers extends over the months of Chaitra to Jyestha (mid-March to mid-May). The average daily temperature during the summer months measures 35 °C, which typically rises to around 40 °C on a few days. The rainy season starts with the first showers of Aashaadha (mid-June) and extends to the middle of Ashvin (September). Most of the rain falls during the southwest monsoon spell, and ranges from about 100 cm in the west to about 165 cm in the east. Indore and the immediately surrounding areas receive an average of 140 cm of rainfall a year. The growing period lasts from 90 to 150 days, during which the average daily temperature stays below 30 °C, but seldom falls below 20 °C. Winter constitutes the longest of the three seasons, extending for about five months (mid-Ashvin to Phalgun, that is, October to mid-March). The average daily temperature ranges from 15 °C to 20 °C, though on some nights it can fall as low as 7 °C. Some cultivators believe that an occasional winter shower during the months of Pausha and Maagha (known as Mawta) helps the early summer wheat and germ crops.[5]

The region resides in the Kathiawar-Gir dry deciduous forests ecoregion.

Vegetation: Tropical dry forest, with scattered teak (Tectona grandis) forests makes up the natural vegetation . The main trees include Butea, Bombax, Anogeissus, Acacia, Buchanania, and Boswellia. The shrubs or small trees include species of Grewia, Ziziphus mauritiana, Casearia, Prosopis, Capparis, Woodfordia, Phyllanthus, and Carissa.

Wildlife: Sambhar (Cervus unicolor), Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), and Chinkara (Gazella bennettii) are some common ungulates.[8] During the last century, deforestation has happened at a fast rate, leading to environmental problems such as acute water scarcity and the danger that the region will become desertified.

Demographics

The population of the Malwa region stood at 18.9 million in 2001, with a population density of a moderate 231/km². The annual birth rate in the region registered 31.6 per 1000, and the death rate 10.3. The infant mortality rate reported at 93.8, slightly higher than the overall rate for the Madhya Pradesh state. Numerous tribes live in the region, including the Bhils (and their allied groups, the Bhilalas, Barelas and Patelias) and the Meenas, who all differ to a remarkable degree from the regional population in their dialects and social life. They encompass a variety of languages and cultures. The government notified some tribes of the region, notably the Kanjars, in the nineteenth century for their criminal activities, but they have since then been denotified. A nomadic tribe from the Marwar region of Rajasthan, the Gadia Lohars (who work as lohars or blacksmiths) visit the region at the start of the agricultural season to repair and sell agricultural tools and implements, stopping temporarily on the outskirts of villages and towns and residing in their ornate metal carts. The Kalbelias constitute another nomadic tribe from Rajasthan that regularly visits the region.[9]

Malwa has a significant number of Dawoodi Bohras, a subsect of Shia Muslims from Gujarat, mostly professional businessmen. Besides speaking the local languages, the Bohras have their own language, Lisan al-Dawat. The Patidars, who probably originated from the Kurmis of Punjab, work mostly as rural farmers, settling in Gujarat around 1400. Periods of sultanate and Maratha rule led to the growth of sizeable Muslim and Marathi communities. A significant number of Jats and Rajputs also live in the region. The Sindhis, who settled in the region after the partition of India, play an important role in the business community. Like neighboring Gujarat and Rajasthan, the region has a significant number of Jains, working mostly as traders and business people. Smaller numbers of Parsis or Zoroastrians, Goan Catholics, Anglo-Indians, and Punjabis call the region home. The Parsis have intimately connected with the growth and evolution of Mhow, a Parsi fire temple and a Tower of Silence.

Economy

The region stands as one of the world's major opium producers. That crop resulted in close connections between the economies of Malwa, the western Indian ports and China, bringing international capital to the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. Malwa opium challenged the East India Company monopoly, supplying Bengal opium to China. That led the British company to impose many restrictions on the production and trade of the drug; eventually, opium trading fled underground. When smuggling became rife, the British eased the restrictions. Today, the region represents one of the largest producers of legal opium in the world. A central, government-owned opium and alkaloid factory operates in the city of Neemuch. Significant illicit opium production operates alongside the government operation, channeling opium into the black market. The headquarters of India's Central Bureau of Narcotics resides in Gwalior.

The region, predominantly agricultural, enjoys the black, volcanic soil ideal for the cultivation of cotton; textile manufacture represents an important industry. Large centers of textile production include Indore, Ujjain and Nagda. Maheshwar has gained renown for its fine Maheshwari saris, and Mandsaur for its coarse woollen blankets. Handicrafts represent an important source of income for the tribal population. Coloured lacquerware from Ratlam, rag dolls from Indore, and papier-mâché articles from Indore, Ujjain and several other centers have become well known. The brown soil in parts of the region enhances the cultivation of such unalu (early summer) crops as wheat, gram (Cicer arietinum) and til (Sesamum indicum). Early winter crops (Syalu) such as millet (Andropogon sorghum), maize (Zea mays), mung bean (Vigna radiata), urad (Vigna mungo), batla (Pisum sativum) and peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) grow well in relatively poor soil. Overall, jowar, rice, wheat, coarse millet, peanuts and pulses, soya bean, cotton, linseed, sesame and sugarcane represent the main crops. Sugar mills operate in numerous small towns. Mandsaur district constitutes the sole producer in India of white and red colored slate, used in the district's 110 slate pencil factories. Apart from that, and a cement factory, the region lacks mineral resources. The region's industries mainly produce consumer goods, although only a few centers of large and medium-scale industries exist, including Indore, Nagda, and Ujjain. Indore has a large-scale factory that produces diesel engines. Pithampur, an industrial town 25 km from Indore, has the nick name the Detroit of India for its heavy concentration of automotive industry. Indore, recognized as the commercial capital of Madhya Pradesh, serves as the main center for trade in textiles and agro-based products. One of the six Indian Institutes of Management, for training managers or regulating professional standards, operates there.

Culture

The culture of Malwa has been significantly influenced by Gujarati and Rajasthani culture, because of their geographic proximity. Marathi influence, as a result of the recent rule by the Marathas, appears as well. The main language used in Malwa, Malvi combines with Hindi as the most popular languages spoken in the cities. That Indo-European language subclassifies as Indo-Aryan, sometimes referred to as Malavi or Ujjaini. Malvi belongs to the Rajasthani branch of languages; Nimadi, spoken in the Nimar region of Madhya Pradesh and in Rajasthan. The dialects of Malvi, in alphabetical order, follow: Bachadi, Bhoyari, Dholewari, Hoshangabadi, Jamral, Katiyai, Malvi Proper, Patvi, Rangari, Rangri, and Sondwari. A survey in 2001 found only four dialects: Ujjaini (in the districts of Ujjain, Indore, Dewas and Sehore), Rajawari (Ratlam, Mandsaur and Neemuch), Umadwari (Rajgarh) and Sondhwari (Jhalawar, in Rajasthan). About 55 percent of the population of Malwa converse in Hindi, while about 40 percent of the population has been classified as literate in Hindi, the official language of the Madhya Pradesh state.[10]

Traditional Malwa food has elements of both Gujarati and Rajasthani cuisine. Traditionally, people served jowar as the staple cereal, but after the green revolution in India, wheat replaced jowar as the most important food crop. Many people in Malwa practice vegetarianism. Since the climate remains mostly dry throughout the year, stored foods such as pulses prevail, with green vegetables seldom eaten. The bhutta ri kees (made with grated corn roasted in ghee and later cooked in milk with spices) constitutes a typical snack of Malwa. People make chakki ri shaak from a wheat dough by washing it under running water, steaming it and then used it in a gravy of curd. The traditional bread of Malwa, called baati/bafla, essentially a small, round ball of wheat flour, roasts over dung cakes in the traditional way. Baati, typically eaten with dal (pulses), while people drip baflas with ghee and soak it with dal. The amli ri kadhi constitutes kadhi made with tamarind instead of yogurt. People enjoy sweet cakes, made of a variety of wheat called tapu, served during religious festivities. People typically eat thulli, a sweet cereal, with milk or yogurt. Traditional desserts include mawa-bati (milk-based sweet similar to Gulab jamun), khoprapak (coconut-based sweet), shreekhand (yogurt based) and malpua.

Lavani, a widely practised form of folk music in southern Malwa, came through the Marathas. The Nirguni Lavani (philosophical) and the Shringari Lavani (erotic) constitute the two of the main genres. The Bhils have their own folk songs, always accompanied by dance. The folk musical modes of Malwa include four or five notes, and in rare cases six. The devotional music of the Nirguni cult prevails throughout Malwa. Legends of Raja Bhoj and Bijori, the Kanjar girl, and the tale of Balabau represent popular themes for folk songs. Insertions known as stobha, commonly used in Malwa music, can occur in four ways: the matra stobha (syllable insertion), varna stobha (letter insertion), shabda stobha (word insertion) and vakya stobha (sentence insertion).[11]

Malwa constituted the center of Sanskrit literature during and after the Gupta period. The region's most famous playwright, Kalidasa, has been considered the greatest Indian writer ever. Three of his plays survive. First, Malavikagnimitra (Malavika and Agnimitra). The second play, Abhijñānaśākuntalam, stands as his Kalidasa's masterpiece, in which he tells the story of king Dushyanta, who falls in love with a girl of lowly birth, the lovely Shakuntala. Third, Vikramuurvashiiya ("Urvashi conquered by valor"). Kalidasa also wrote the epic poems Raghuvamsha ("Dynasty of Raghu"), Ritusamhāra and Kumarasambhava ("Birth of the war god"), as well as the lyric Meghaduuta ("The cloud messenger").

Swang, a popular dance form in Malwa, has roots that go back to the origins of the Indian theatre tradition in the first millennium B.C.E. Men enacted women's roles, as custom prohibited women from performing in the dance-drama form. Swang incorporates suitable theatrics and mimicry, accompanied alternatately by song and dialogue. The genre has a dialogue-oriented character rather than movement-oriented.[12]

Mandana (literally painting) wall and floor paintings constitute the best-known painting traditions of Malwa. White drawings stand out in contrast to the base material consisting of a mixture of red clay and cow dung. Peacocks, cats, lions, goojari, bawari, the Buddhist swastika and chowk represent some motifs of that style. Young girls make a ritual wall paintings, sanjhya, during the annual period when Hindus remember and offer ritual oblation to their ancestors. Malwa miniature paintings have earned renown for their intricate brushwork.[13] In the seventeenth century, an offshoot of the Rajasthani school of miniature painting, known as Malwa painting, centered largely in Malwa and Bundelkhand. The school has preserved the style of the earliest examples, such as the Rasikapriya series dated 1636 (after a poem analyzing the love sentiment) and the Amaru Sataka (a seventeenth century Sanskrit poem). The paintings from that school have flat compositions on black and chocolate-brown backgrounds, with figures shown against a solid color patch, and architecture painted in vibrant colours.[14]

The Simhastha mela, held every twelve years, constitutes the biggest festival of Malwa. More than a million pilgrims take a holy dip in river Shipra during the event. The festival of Gana-gour honors Shiva and Parvati. The history of that festival goes back to Rano Bai, whose had his parental home in Malwa, but married in Rajasthan. Rano Bai felt strongly attached to Malwa, although she had to stay in Rajasthan. After marriage, her husband's family allowed her to visit Malwa only once a year; Gana-gour symbolises those annual return visits. Women in the region observe the festival once in the month of Chaitra (mid-March) and Bhadra (mid-August). The girls of the region celebrate Ghadlya (earthen pot) festival, gathering to visit every house in their village in the evenings, carrying earthen pots with holes for the light from oil lamps inside to escape. In front of every house, the girls recite songs connected with the Ghadlya and receive food or money in return. They celebrate Gordhan festival on the 16th day in the month of Kartika. The Bhils of the region sing Heeda anecdotal songs to the cattle, while the women sing the Chandrawali song, associated with Krishna's romance.[15]

Malwa hold the most popular fairs in the months of Phalguna, Chaitra, Bhadra, Ashvin, and Kartik. Remarkable among them, the Chaitra fair, held at Biaora, and the Gal yatras, held at more than two dozen villages in Malwa. The villages hold many fairs in the tenth day of the month of Bhadra to mark the birth of Tejaji. Ratlam hosts the Triveni mela, while other fairs take place in Kartika at Ujjain, Mandhata (Nimad), Nayagaon, among others.[16]

Religious and historical sites

Places of historical or religious significance represent the main tourist destinations in Malwa. The river Shipra and the city of Ujjain have been regarded as sacred for thousands of years. The Mahakal Temple of Ujjain numbers among the twelve jyotirlingas. Ujjain has over 100 other ancient temples, including Harsidhhi, Chintaman Ganesh, Gadh Kalika, Kaal Bhairava, and Mangalnath. The Kalideh Palace, on the outskirts of the city, provides a fine example of ancient Indian architecture. The Bhartrihari caves associate with interesting legends. Since the fourth century B.C.E., Ujjain has enjoyed the reputation of being India's Greenwich,[17] as the first meridian of longitude of the Hindu geographers. Jai Singh II built the observatory, one of the four such observatories in India and features ancient astronomical devices. The Simhastha mela, celebrated every twelve years, starts on the full moon day in Chaitra (April) and continues into Vaishakha (May) until the next full moon day.

Mandu had been, originally, the fort capital of the Parmar rulers. Towards the end of the thirteenth century, the Sultans of Malwa ruled, the first naming it Shadiabad (city of joy). Remaining as the capital, the sultans built exquisite palaces like the Jahaz Mahal and Hindola Mahal, ornamental canals, baths and pavilions. The massive Jami Masjid and Hoshang Shah's tomb provided inspiration to the designers of the Taj Mahal centuries later. Baz Bahadur built a huge palace in Mandu in the sixteenth century. Other notable historical monuments include Rewa Kund, Rupmati's Pavillion, Nilkanth Mahal, Hathi Mahal, Darya Khan's Tomb, Dai ka Mahal, Malik Mughit's Mosque, and Jali Mahal.

Maheshwar, a town on the northern bank of Narmada River that served as the capital of the Indore state under Rajmata Ahilya Devi Holkar, sits close to Mandu. The Maratha rajwada (fort) constitutes the main attraction. A life-size statue of Rani Ahilya sits on a throne within the fort complex. Dhar served as the capital of Malwa before Mandu became the capital in 1405. The fort has fallen into ruins but offers a panoramic view. Worshippers still use the Bhojashala Mosque (built in 1400) as a place of worship on Fridays. The abandoned Lat Masjid (1405) and the tomb of Kamal Maula (early fifteenth century), a Muslim saint, number among other places of interest.

Rajmata Ahilya Devi Holkar planned and built Modern Indore, the grand Lal Baag Palace one of its grandest monuments. The Bada Ganpati temple houses possibly the largest Ganesh idol in the world, measuring 7.6 m from crown to foot. The Kanch Mandir, a Jain temple, stands entirely inlaid with glass. The Town Hall, built in 1904, in indo-gothic style, had been renamed Mahatma Gandhi Hall in 1948 from King Edward Hall. The chhatris, tombs or cenotaphs, had been erected in memory of dead Holkar rulers and their family members.

The shrine of Hussain Tekri, built by the Nawab of Jaora, Mohammad Iftikhar Ali Khan Bahadur, in the nineteenth century, sits on the outskirts of Jaora in the Ratlam district. Mohammad Iftikhar Ali Khan Bahadur had been buried in the same graveyard where Hussain Tekri lay buried. During the month of Moharram, thousands of people from all over the world visit the shrine of Hazrat Imam Hussain, a replica of the Iraqi original. The place, famous for the rituals called Hajri, has a reputation of curing mental illness.

Notes

- ↑ J. Jacobson, Early Stone Age Habitation Sites in Eastern Malwa, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 119 (4).

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, Malwa plateau.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Encyclopedia Britannica, Malwa. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ M.H.Panhwar, Sindh: The Archaeological Museum of the world. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 S.H. Ahmad, Anthropometric Measurements and Ethnic Affinities of the Bhil and Their Allied Groups of Malwa Area (Anthropological Survey of India, 1991, ISBN 81-85579-07-5).

- ↑ KSGEO, Geochronological Study of the Deccan Volcanism by the 40Ar-39Ar Method. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Mantle Plumes, The Deccan. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ NIC, Dewas district. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Native Planet, Kalbeliya nomads. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Ethnologue, Malwa. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Web India, Folk music of Madhya Pradesh. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Boloji, "Swang"—The Folk Dance of Malwa. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ NIC, Paintings of Mewar and Malwa.

- ↑ EB, Malwa painting. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Web India, Festivals of Madhya Pradesh. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Web India Fairs of Madhya Pradesh. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ NIC, Ujjain district official portal. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahmad, S. H., Anthropometric Measurements and Ethnic Affinities of the Bhil and Their Allied Groups of Malwa Area. Anthropological Survey of India, 1991. ISBN 8185579075.

- Chakrabarti, Manika. Malwa in Post-Maurya Period: A Critical Study with Special Emphasis on Numismatic Evidences. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, 1981. OCLC 10467373

- Day, Upendra Nath. Medieval Malwa: A Political and Cultural History 1401–1562. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1965. OCLC 934073

- Farooqui, Amar. Smuggling as Subversion: Colonialism, Indian Merchants, and the Politics of Opium, 1790–1843. Lexington Books, 2005. ISBN 0739108867.

- Jain, Kailash Chand, Malwa Through the Ages From the Earliest Times to 1305 C.E. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1972. OCLC 723805

- Khare, M.D. Splendour of Malwa Paintings. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1983. OCLC: 15415800.

- Joshi, Ramchandra Vinayak. Stone Age Cultures of Central India. Poona: Deccan College, 1978. OCLC 5834725

- Malcolm, Sir John. A Memoir of Central India Including Malwa and Adjoining Provinces. Calcutta: Spink, 1880. ISBN 8173051992.

- Seth, K.N. The Growth of the Paramara Power in Malwa. Bhopal: Progress Publishers, 1978. OCLC 8931757

- Sharma, R.K. (ed.). Art of the Paramaras of Malwa. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1979. OCLC 7066405

- Sircar, D.C. Ancient Malwa and the Vikramaditya Tradition. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1969. ISBN 8121503485.

- Singh, Raghubir. Malwa in Transition. Laurier Books, 1993. ISBN 8120607503.

- Srivastava, Khushhalilal. The Revolt of 1857 in Central India-Malwa. Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1966. OCLC 936365

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.