Manasseh Ben Israel

Manoel Dias Soeiro (1604 - November 20, 1657), better known by his Hebrew name Manasseh ben Israel (also spelled "Menasseh"), was a Portuguese-Jewish rabbi, kabbalist, writer, diplomat, printer, and publisher. Best known for his work in winning the Jews the right to live in England, he was also the founder of the first Hebrew printing press in The Netherlands in 1626.

Born to a family of Portuguese Marranos who settled in Amsterdam, Manasseh rose to prominence as a rabbi in the city's growing Jewish community. He won fame for his work El Conciliador, which sought to reconcile apparent contradictions in the Hebrew Bible and was one of the first Jewish works to gain a Christian readership. His writings on the messianic prophecies of the restoration of Israel gained a wide readership in England. He journeyed in London near the end of his life and was instrumental in the decision of Oliver Cromwell's government to allow Jews to live in the country, from which they had been expelled in 1290.

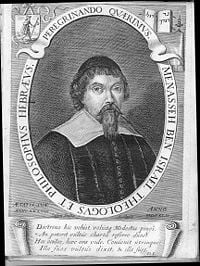

He was acquainted with many leading Christian thinkers and was also the friend of Rembrandt, who illustrated one of his books and drew his portrait. One of Manasseh's students was the philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

Life

Background and early years

Manasseh's father had been a Marranoâa Jew who professed Christianity in public but practiced Judaism in private. After his father was forced by the Inquisition to appear in public as a penitent for his secret Judaism in the auto da fé of August 3, 1603, his parents fled Lisbon, eventually settling, like many other Portuguese Jews, in Amsterdam. The actual place of Menasseh's birth is uncertain, with sources ranging from Lisbon to Madeira Island, and New Rochelle in western France. At birth he was given the Portuguese name, Manoel Dias Soeiro.

The family moved to Amsterdam in 1610, when the Netherlands was in the process of religious revolt during the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648), arriving during the truce mediated by France and England at The Hague. Manasseh was educated under Rabbi Isaac Uzziel of Fez, the rabbi of Amsterdam's new congregation Neveh Shalom.

Rabbi, scholar, and printer

In 1622, Manasseh married Rachel, a member of the Abravanel familyâone of the oldest and most distinguished Jewish families of the Iberian peninsula. He soon became distinguished as one of the best scholars and orators of Amsterdam's Jewish community and was elected to the city's rabbinical council. Manasseh also started the first Hebrew printing press in Holland, since neither preaching nor private tuition was sufficient to provide him with an adequate livelihood. He quickly produced a Hebrew prayer book (January 12, 1627), an index to the Midrash Rabbah (1628), a Hebrew grammar written by his teacher Isaac Uzziel (1628), and an elegant edition of the Mishnah.

Manasseh also rose to eminence as an author. One of his earliest works, El Conciliador, an attempt to reconcile apparent discrepancies in various parts of the Hebrew Bible, won immediate fame. Written in fluent Spanish, the book was one of the first Jewish works in a modern language to gain an interest among Christian readers. Some of the best scholars of his time corresponded with him as a result, among them Gerhard Johann Vossius, Hugo Grotius, and Pierre Daniel Huet. Queen Christina of Sweden was also acquainted with him, and he was on the point of convincing her to open Scandinavia to the Jews when she abdicated the throne.

Notwithstanding this wide fame, Manasseh still found it difficult to obtain a living for himself, his wife, and three children. Around this time, the three synagogues of Amsterdam were reorganized, and Manasseh may have lost his position as rabbi of the Neveh Shalom. In 1638, he intended to join his brother-in-law in Brazil, where the latter had previously moved on a joint business venture with Manasseh. At this point, however, the wealthy Pereira brothers established a Jewish academy in Amsterdam, offering Manasseh a position as its head (1640). He was thus enabled to devote himself entirely to scholarship, writing, and his ever-widening correspondence with Jewish and Christian literati.

Kabbalistic and messianic ideas

Manasseh was profoundly interested in messianic issues, which had begun to gain popularity among European Jews. For example, he became convinced of the Davidic origin of the Abravanel family, from which his wife and children were descended. He also believed that the restoration to the Holy Land could not take place until the Jews had spread into and inhabited every part of the world.

He also expressed many opinions about the Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical traditional. However, he did not write of these views in modern languages intended to be read by Gentiles. His major work on kabbalistic matters was his Nishmat Hayim, a Hebrew treatise dealing with the the Jewish concept of reincarnation, which had gained prominence through the work of Isaac Luria.

In 1644, Manasseh met Antonio de Montesinos, who convinced him that the South America Andes' Indians were the descendants of the lost ten tribes of Israel. This supposed discovery gave a new impulse to Menasseh's messianic hopes.

Opening England to the Jews

Filled with this idea, Manasseh turned his attention to England, where the Jews had been expelled since 1290. He found interest for his views among English Christians, especially the Puritans. Oliver Cromwell, for example, had been moved to sympathy with the Jewish cause, chiefly because he foresaw the importance for English commerce of the presence of the Jewish merchant princes, some of whom had already found their way to London. Jews had already received full rights in the colony of Surinam, which had been English since 1650. In the same year, there appeared an English version of Manasseh's Hope of Israel, a tract which deeply impressed public opinion. One of the replies, "An Epistle to the Learned Manasseh ben Israel" (London, 1650), was written by Sir Edward Spencer, member of Parliament for Middlesex. Another appeared anonymously under the title "The Great Deliverance of the Whole House of Israel." Both of these replies, however, insisted upon the need of Jewish conversion to Christianity before the messianic prophecies about Israel could be fulfilled, and it was probably for this reason that the matter was dropped by Manasseh.

Meanwhile, Cromwell's attention had been drawn to the subject of Jewish immigration, and his representative at Amsterdam was directed to communicate with Manasseh. As a result, Manasseh was scheduled to address the English council of state on the subject of the Jewish readmission to England, and a pass was issued to enable him to travel there. After the cessation of the war between Holland and England, Manasseh sent his son Samuel and his nephew David Dormido to consult with Cromwell. They were unsuccessful, however, and Samuel returned to Amsterdam in 1655 to persuade his father to attempt the task himself.

Manasseh arrived in London in the same year, and one of his first acts there was to issue his Humble Addresses to the Lord Protector. Cromwell summoned a conference at Whitehall to discuss the issue of Jewish readmission in December 1655. Some of the most notable statesmen, lawyers, and theologians of the day were summoned to this meeting. The chief practical result was the declaration of judges Glynne and Steele that "there was no law which forbade the Jews' return to England." Though nothing was done to legalize the position of the Jews officially, the door was opened to their gradual return. The diarist John Evelyn wrote on date December 14, 1655: "Now were the Jews admitted." In the meantime Manasseh replied to the anti-Jewish tract of Puritan polemicist William Prynne in Vindiciae judaeorum (1656), considered one of Manasseh's finest works.

Soon after Manasseh left London, Cromwell granted him a pension, but he died before he could enjoy it. Death overtook him at Middleburg in the Netherlands in the winter of 1657, as he was conveying the body of his son Samuel home for burial. His tomb is in the Beit Hayim of Ouderkerk a/d Amstel.

Legacy

Manasseh ben Israel's greatest legacy was his attempt to gain the readmission of the Jews to England. Although Jewish immigration was not yet formally allowed, the Jews living in London without permission were allowed to remain, and the Jewish community there had grown to about 300 by the end of the seventeenth century. Manasseh was also the teacher of Baruch Spinoza, the greatest Jewish philosopher of his age, although Spinoza was excommunicated for his views by the rabbis of Amsterdam while Manasseh was away in England.

Manasseh was also a friend of Rembrandt, who painted his portrait and engraved four etchings to illustrate Manasseh's Piedra gloriosa. The portrait is disputed, as some claim it does not resemble other contemporary pictures of Manasseh, while many others insist that only the style of dress is dissimilar.

Manasseh reportedly read and understood ten languages, and he printed works in fiveâHebrew, Latin, Portuguese, English, and Spanish. His major work is his Nishmat Hayim a kabbalistic treatise in Hebrew dealing with kabbalistic topics, especially the Jewish concept of reincarnation. It was published by his son Samuel six years before they both died. His El Conciliador was more influential, stimulating readership among Christians as well as Jews. His pamphlets connected with the return of the Jews to England were republished through the Jewish Historical Society of England (London, 1901). Manasseh also wrote a series of works in Latin on various theological problems, all printed at AmsterdamâDe Creatione (1635), De Resurrectione Mortuorum (1635), De Termino Vitæ (1639). He wrote an essay in Spanish, De la Fraglidad Humana (1642); and a list of the 613 Jewish commandments in Portuguese, entitled Thesoro dos Dinim (1645). His Vindiciæ Judæorum was translated into German, with a preface by Moses Mendelssohn. Several of his works are now available in English.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fuks, Lajb, Rena Fuks, and Manasseh ben Israel. Menasseh Ben Israel As a Bookseller in the Light of New Data / L. and R. Fuks. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1981. OCLC 8147756

- Kaplan, Yosef, Richard H. Popkin, and Henry Méchoulan. Menasseh Ben Israel and His World. Brill's studies in intellectual history, v. 15. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989. ISBN 9789004091146.

- Manasseh ben Israel. The Conciliator of R. Manasseh Ben Israel; A Reconcilement of the Apparent Contradictions in Holy Scripture, to Which Are Added Explanatory Notes, and Biographical Notices of the Quoted Authorities. New York: Hermon Press, 1972. ISBN 9780872030367.

- â, with Moses Wall, Henry Méchoulan, and Gérard Nahon. The Hope of Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 9780197100547.

- Roth, Cecil. A Life of Menasseh Ben Israel, Rabbi, Printer, and Diplomat. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1945. OCLC 9982555

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.