Maximus the Confessor

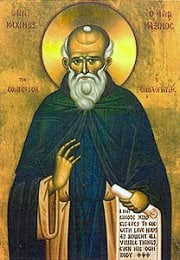

| Saint Maximus | |

|---|---|

Icon of St. Maximus | |

| Confessor, Theologian, Homogoletes | |

| Born | c. 580 in Constantinople or Palestine |

| Died | August 13, 662 in exile in Georgia (Eurasia) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast | August 13 in the West, January 21 in the East |

Saint Maximus the Confessor (also known as Maximus the Theologian and Maximus of Constantinople) (c. 580 - August 13, 662 C.E.) was a Christian monk, theologian, and scholar. In his early life, he was a civil servant and an aide to the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610-641 C.E.). However, he gave up his life in the political sphere in order to devote himself to religious observance as a cenobite.[1]

After moving to Carthage, Maximus apprenticed himself to Saint Sophronius, who instructed him in the theological teachings of Gregory of Nazianzus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, as well as the philosophical speculations of the Neo-Platonists. Under these influences, the young novice began his new vocation as an author and theologian.

When one of his friends began espousing the Christological position later known as Monothelitism, Maximus was drawn into the controversy, supporting the Chalcedonian position that Jesus had both a human and a divine will. After various theological debates and political maneuverings, he was eventually exiled for his beliefs and died soon after. However, his theology was vindicated by the Third Council of Constantinople and he was publicly sanctified soon after his death. Maximus is venerated in both Western Christianity and Eastern Christianity, and his feast day is August 13 in the former, and January 21 in the latter.

Life

Early life

Very little is known about the details of Maximus' life prior to his involvement in the theological and political conflicts of the Monothelite controversy. Maximus was most likely born in Constantinople, albeit a biography, written by his Maronite opponents, has him born in Palestine.[2] Maximus was born into Byzantine nobility, as indicated by his appointment to the position of personal secretary to Emperor Heraclius (610-641 C.E.).[3][4] For reasons unknown,[5] Maximus left public life in 630, and took monastic vows at a monastery in Chrysopolis (also known as Scutari, the modern Turkish city of Üsküdar), a city across the Bosphorus from Constantinople. In his years in Chrysopolis, Maximus was elevated to the position of Abbot of the monastery.[6]

When the Persian Empire conquered Anatolia, Maximus was forced to flee to a monastery near Carthage. It was there that he came under the tutelage of Saint Sophronius, and began studying the Christological writings of Gregory of Nazianzus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.[7] It was also during his stay in Carthage that Maximus began his career as a theological and spiritual writer.[2] At this time, Maximus also became esteemed as a holy man by both the exarch (provincial governor) and the population, ostensibly becoming an influential (though unofficial) political adviser and spiritual head in North Africa.

Involvement in Monothelite controversy

While Maximus was in Carthage, a controversy arose regarding how to understand the interaction between the human and divine natures within the person of Jesus. This Christological debate was the latest development in the disagreements following the Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E., which intensified after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 C.E. The Monothelite position was a compromise to appease those Christologies declared to be heretical at Chalcedon, as it adhered to the Chalcedonian definition of the hypostatic union: that Christ possessed two natures, one divine and one human, which were united in His incarnate flesh.[8] However, it went on to say that Christ had only a single, indivisible will (which was frequently conflated with the divine will alone).[9] Indeed, the name for the heresy itself is derived from the Greek for "one will." This theological perspective came to have tremendous authority, as it was endorsed as the official Christology of the Holy Roman Empire in the Ecthesis of Heraclius (an imperial edict dated 638 C.E.).[9]

The Monothelite position was promulgated by Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople and by Maximus's friend (and the successor to the Abbacy at Chrysopolis), Pyrrhus,[10] who became, for a brief period, the Patriarch of Constantinople (638-641). After his friend's exile, Maximus and the deposed Patriarch held a public debate on the issue of Monothelitism. In the debate, which was held in the presence of many North African bishops, Maximus vehemently defended the orthodox (though politically unpopular) position that Jesus possessed both a human and a divine will. Convinced by his compatriot's adept theologizing, Pyrrhus admitted the error of the Monothelite position, and agreed to travel to Rome, where he could recant his previous views and submit to the authority of Pope Theodore I (who supported the Chalcedonian Christology) in 645 .[11] However, on the death on Emperor Heraclius and the ascension of Emperor Constans II, Pyrrhus returned to Constantinople and recanted of his acceptance of the Dyothelite ("two wills") position—most likely due to political considerations, as he had "abandoned hope of being restored to the patriarchal throne by Gregory [the imperial exarch in Carthage] and the anti-Monothelites."[12]

At this time, Maximus may have remained in Rome, because he was present when the newly elected Pope Martin I convened a gathering of bishops at the Lateran Basilica in 649.[13] The 105 bishops in attendance officially condemned Monothelitism, as recorded in the official acts of the synod, which some believe may have been written by Maximus.[14] It was in Rome that Pope Martin and Maximus were arrested in 653 C.E. under orders from Constans II, who, in keeping with the Ecthesis of Heraclius, supported the Monothelite doctrine. Pope Martin was condemned without a trial, and died before he could be sent to the Imperial Capital.[15]

Trial and exile

Maximus' refusal to accept Monothelitism caused him to be brought to the imperial capital to be tried as a heretic in 655 C.E., as the Monothelite position had gained the favor of both the Emperor and the Patriarch of Constantinople. In spite of tremendous secular and religious pressure, Maximus stood behind his Dyothelite theology, for which he was "sentenced to banishment at Bizya, in Thrace, were he suffered greatly from cold, hunger, and neglect."[16] Throughout this difficult time, the erstwhile abbot was repeatedly petitioned by the emperor, who offered a full pardon (and even a position of authority) if he would simply accede to the imperially-sanctioned theology. As Louth cogently summarizes,

- Resistance to Monothelitism was now virtually reduced to one man, the monk Maximus.... At his first trial in 655, [he] was first of all accused, like Martin, of treason.... Accusations then turned to theological matters, in which Maximus denied that any emperor had the right to encroach on the rights of the priesthood and define dogma."[17]

In 662 C.E., Maximus (and his two loyal disciples) were placed on trial once more, and were once more convicted of heresy. Following the trial, Maximus was tortured, having his tongue cut out (to silence his "treasonous" critiques of the state) and his right hand cut off (so that he could no longer write epistles contrary to the official theology).[2] Maximus was then exiled to the Lazica or Colchis region of Georgia (perhaps the city of Batum), where, on August 13, 662 C.E., his eighty-year old frame succumbed to the indignities visited upon it.[18] The events of the trials of Maximus were recorded by his pupil, Anastasius Bibliothecarius, which served as part of the source material for the hagiographical accounts of his life produced in the years that followed.

Legacy

Along with Pope Martin I, Maximus was vindicated by the Third Council of Constantinople (the Sixth Ecumenical Council, 680-681 C.E.), which declared that Christ possessed both a human and a divine will. With this declaration, Monothelitism became heresy (which consequently meant that Maximus was innocent of all charges that had been laid against him).[19]

Maximus is among those Christians who were venerated as saints shortly after their deaths. More specifically, the atrocities visited upon the simple monk, plus the eventual vindication of his theological position made him extremely popular within a generation of his death. This cause was significantly aided by accounts of miracles occurring at and around his tomb.[20] In the Roman Catholic Church the veneration of Maximus began prior to the foundation of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, meaning that there was never a formal canonization procedure.

Theology

As a student of Pseudo-Dionysius (Denys the Aeropagite), Maximus was one of many Christian theologians who preserved and interpreted Neo-Platonic philosophy, including the thought of such figures as Plotinus and Proclus.

- Maximus is heir to all of this: but, more than that, in his own theological reflection he works out in greater—and more practical—detail what in Denys is often not much more than splendid and inspiring rhetoric. How the cosmos has been fractured, and how it is healed—how this is achieved in the liturgy—what contributions the Christian ascetic struggle has to make: all this can be found, drawn together into an inspiring vision, in the work of the Confessor.[21] These contributions were seen to be significant enough that Maximus' work on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite was continued by John Scotus Erigena at the formal request of Charles the Bald.[22]

The Platonic influence on Maximus' thought can be seen most clearly in his theological anthropology. Here, Maximus adopted the Platonic model of exidus-reditus (exit and return), teaching that humanity was made in the image of God and that the purpose of salvation is to restore us to unity with God.[23] This emphasis on divinization or theosis helped secure Maximus' place in Eastern theology, as these concepts have always held an important place in Eastern Christianity.[24] Christologically, Maximus insisted on a strict Dyophysitism, which can be seen as a corollary of the emphasis on theosis. In terms of salvation, humanity is intended to be fully united with God. This is possible for Maximus because God was first fully united with humanity in the incarnation.[22] If Christ did not become fully human (if, for example, he only had a divine and not a human will), then salvation was no longer possible, as humanity could not become fully divine.[23] As suggested by Pelikan, the Monophysite positions, "despite their attractiveness to a Christian spirituality based on a yearning for union with God, ... [undercuts] this spirituality by severing the bond between our humanity and the humanity of Jesus Christ."[25]

Other than the work by Scotus in Ireland, Maximus was largely overlooked by Western theologians until recent years.[26] The situation is different in Eastern Christianity, where Maximus has always been influential. For example, at least two influential Eastern theologians (Simeon the New Theologian and Gregory Palamas) are seen as direct intellectual heirs to Maximus. Further, a number of Maximus's works are included in the Greek Philokalia—a collection of some of the most influential Greek Christian writers.

Maximus' Writings

- Ambigua - An exploration of difficult passages in the work of Pseudo-Dionysius and Gregory of Nazianzus, focusing on Christological issues. This was later translated by John Scotus.

- Centuries on Love and Centuries on Theology - maxims about proper Christian living, arranged into groupings of one hundred.

- Commentary on Psalm 59

- Commentary on the Lord's Prayer

- Mystagogy - A commentary and meditation on the Eucharistic liturgy.

- On the Ascetic Life - a discussion on the monastic rule of life.

- Questions to Thalassius - a lengthy exposition on various Scriptural texts.

- Scholia - commentary on the earlier writings of Pseudo-Dionysius.

- Various Hymns

Notes

- ↑ A cenobite is a monk living in a monastic community.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 George C. Berthold, "Maximus Confessor" in The Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson (New York: Garland Publishing, 1997, ISBN 0-8153-1663-1).

- ↑ "Maximos, St., Confessor" in the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. F.L. Cross (London: Oxford Press, 1958, ISBN 0-1921-1522-7).

- ↑ See also the article in the Catholic Encyclopedia, which describes the saint as a "great man [who] was of a noble family of Constantinople." Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Though some hagiographical sources speculate that this flight was due to the fact that "he was made uncomfortable by the emperor's support of what he recognized as heretical opinions," this explanation is somewhat improbable, as Maximus had yet to formally study theology (at least based on extant accounts of his life). See Butler's Lives of the Saints Volume III, edited by Herbert J. Thurston and Donald Attwater, (London: Burns and Oates, 1981, ISBN 0-86012-112-7), 320.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan, "Introduction" to Maximus the Confessor: Selected Writings (New York: Paulist Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8091-2659-1). See also the Catholic Encyclopedia Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ Andrew Louth, Maximus the Confessor (London: Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-11846-80), 5-6.

- ↑ Louth, pp. 56-57..

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 See the Catholic Encyclopedia, "Monothelitism". Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Butler's Lives of the Saints Volume III, edited by Herbert J. Thurston and Donald Attwater, (London: Burns and Oates, 1981), 321. ISBN 0-86012-112-7. See also the Catholic Encyclopedia Retrieved January 15, 2007. "The first action of St. Maximus that we know of in this affair is a letter sent by him to Pyrrhus, then an abbot at Chrysopolis ..."

- ↑ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume IV: Medieval Christianity. 590-1073 C.E. (Online Edition) §111. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ↑ Louth, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ "Maximus the Confessor," in The Westminster Dictionary of Church History, ed. Jerald Brauer (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1971, ISBN 0-6642-1285-9). This gathering is generally known as the First or Second Lateran Synod, as it is not recognized as an official Ecumenical Council.

- ↑ For example, this claim is made in Gerald Berthold's "Maximus Confessor" in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (New York: Garland, 1997, ISBN 0-8153-1663-1).

- ↑ David Hughes Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-1986-9149-1), 288. This made Martin the last Bishop of Rome to be venerated as a martyr.

- ↑ Butler's Lives of the Saints Volume III, edited by Herbert J. Thurston and Donald Attwater (London: Burns and Oates, 1981, ISBN 0-86012-112-7), 321.

- ↑ Louth, pg. 18.

- ↑ See the Catholic Forum The injuries Maximus sustained while being tortured and the conditions of his exile both contributed to his death, causing Maximus to be considered a martyr by many. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ Louth, pg. 18. Louth notes that, despite his staunch defense of the orthodox position, Maximus is not explicitly mentioned in the surviving records of the council.

- ↑ For example, from the biography provided by the Orthodox Church in America "Three candles appeared over the grave of St Maximus and burned miraculously. This was a sign that St Maximus was a beacon of Orthodoxy during his lifetime, and continues to shine forth as an example of virtue for all. Many healings occurred at his tomb." Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ Louth, pg. 31.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Catholic Encyclopedia Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Maximos, St., Confessor" in the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. F.L. Cross (London: Oxford Press, 1958, ISBN 0-1921-1522-7). One sees this especially in Maximus' Mystagogy and Ambigua.

- ↑ "Maximus the Confessor" in Michael O'Carroll, Trinitas: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Trinity (Delaware: Michael Glazier, Inc, 1987, ISBN 0-8146-5595-5).

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan, "Introduction" to Maximus the Confessor: Selected Writings (New York: Paulist Press, 1985, 7. ISBN 0-8091-2659-1).

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints (David Hugh Farmer), which does not have an entry for Maximus, is an excellent example of how the West overlooked Maximus for years. Conversely, the Systematic Theology of Robert Jenson, written in the late 1990s, is an example of how Western theologians are rediscovering Maximus. See also "Maximus the Confessor" in Michael O'Carroll, Trinitas: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Trinity (Delaware: Michael Glazier, Inc, 1987, ISBN 0-8146-5595-50. O'Carroll names Hans Urs von Balthasar as a "pioneer" in the Western rediscovery of Maximus.

Further reading

Collections of Maximus' writings in Print

- Maximus Confessor: Selected Writings (Classics of Western Spirituality). Ed. George C. Berthold. Paulist Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8091-2659-1.

- On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ: Selected Writings from St. Maximus the Confessor (St. Vladimir's Seminary Press "Popular Patristics" Series). Ed. & Trans Paul M. Blowers, Robert Louis Wilken. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8814-1249-X

- St. Maximus the Confessor: The Ascetic Life, The Four Centuries on Charity (Ancient Christian Writers). Ed. Polycarp Sherwood. Paulist Press, 1955. ISBN 0-8091-0258-7

- Maximus the Confessor and his Companions (Documents from Exile) (Oxford Early Christian Texts). Ed. and Trans. Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-1982-9991-5

On the theology of Saint Maximus

- von Balthasar, Hans Uls. Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor. Ignatius Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8987-0758-7

- Bathrellos, Demetrios. The Byzantine Christ: Person, Nature, and Will in the Christology of Saint Maximus the Confessor. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-1992-5864-3

- Nichols, Aiden. Byzantine Gospel: Maximus the Confessor in Modern Scholarship. T. & T. Clark Publishers, 1994. ISBN 0-5670-9651-3

- Toronen, Melchisedec. Union and Distinction in the Thought of St Maximus the Confessor. Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-1992-9611-1

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- St. Maximus of Constantinople Catholic Encyclopedia.

- St. Maximus the Confessor Orthodox Church in America.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.