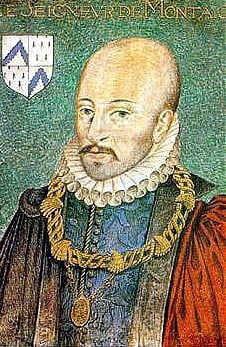

Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne ([miʃɛl ekɛm də mɔ̃tɛɲ]) (February 28, 1533 – September 13, 1592) was one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance. Montaigne is known for inventing the essay. Although there are other authors who wrote in an autobiographical style on intellectual issues—Saint Augustine was an example from the ancient world—Montaigne was the first popularize the tone and style of what would become the essay form. He is renowned for his effortless ability to merge serious intellectual speculation with casual anecdotes and autobiography. Montaigne's massive work, the Essais, contains some of the most widely influential essays ever written, among them the essay "On Cannibals," where Montaigne famously defended the rights and dignity of native peoples, and "An Apology for Raymond Sebond," where he argued vehemently against dogmatic thinking. Montaigne is one of the most important French writers of the Renaissance, having a direct influence on writers the world over, from Shakespeare to Emerson, from Nietzsche to Rousseau.

In his own time, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. His tendency to diverge into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as a detriment rather than an innovation, and his stated motto that "I am myself the matter of my book" was viewed by contemporary writers as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne would be recognized as expressing candidly the "zeitgeist" of his age, perhaps more so than any other author of his time, specifically because he would refer so often to his personal reflections and experiences. Remarkably modern even to readers today, Montaigne's conviction to examine the world through the lens of the only thing he can depend on inviolably—his own self—makes him one of the most honest and accessible of all writers. The entire field of modern literary non-fiction owes its genesis to Montaigne, and non-fiction writers of all kinds—from essayists to journalists to historians—continue to read Montaigne for his masterful balance of intellectual knowledge and graceful style.

Life

Montaigne was born in Périgord on the family estate, Château de Montaigne, in a town now called Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, not far from Bordeaux. The family was very rich; his grandfather, Ramon Eyquem, had made a fortune as a herring merchant and had bought the estate in 1477. His father, Pierre Eyquem, was a soldier in Italy for a time, developing some very progressive views on education there; he had also been the mayor of Bordeaux. His mother, Antoinette de Louppes, came from a wealthy Spanish Jewish family, but was herself raised Protestant. Although she lived a great part of Montaigne's life near him, and even survived him, Montaigne doesn't make any mention of her in his work. In contrast, Montaigne's relationship with his father played a prominent role in his life and work.

From the moment of his birth, Montaigne's education followed a pedagogical plan sketched out by his father, based on the advice of the latter's humanist friends. Soon after his birth, Montaigne was brought to a small cottage, where he lived the first three years of life in the sole company of a peasant family, "in order to," according to the elder Montaigne, "approximate the boy to the people, and to the life conditions of the people, who need our help." After these first spartan years spent amongst the lowest social class, Montaigne was brought back to the Château. The objective there was for Latin to become his first language. His intellectual education was assigned to a German tutor (a doctor named Horstanus who couldn't speak French); and strict orders were given to him and to everyone in the castle (servants included) to always speak to the boy in Latin—and even to use the language among themselves anytime he was around. The Latin education of Montaigne was accompanied by constant intellectual and spiritual stimulation. The sciences were presented to him in most pedagogical ways: through games, conversation, exercises of solitary meditation, etc., but never through books. Music was played from the moment of Montaigne's awakening. An épinettier—a zither-player—constantly followed Montaigne and his tutor, playing a tune any time the boy became bored or tired. When he wasn't in the mood for music, he could do whatever he wished: play games, sleep, be alone—most important of all was that the boy wouldn't be obliged to anything, but that, at the same time, he everything would be available in order to take advantage of his freedom.

Around the year 1539, Montaigne was sent to study at a prestigious boarding school in Bordeaux, the Collège de Guyenne, afterward studying law in Toulouse and entering a career in the legal system. Montaigne was a counselor of the Court des Aides of Périgueux, and in 1557 he was appointed counselor of the Parliament in Bordeaux. While serving at the Bordeaux Parliament, he became very close friends with the humanist writer Étienne de la Boétie whose death in 1563 deeply influenced Montaigne. From 1561 to 1563 Montaigne was present at the court of King Charles IX.

Montaigne married in 1565; he had five daughters, but only one survived childhood, and he mentioned them only scantily in his writings.

Following the petition of his father, Montaigne started to work on the first translation of the Spanish monk, Raymond Sebond's Theologia naturalis, which he published a year after his father's death in 1568. After his father's death he inherited the Château de Montaigne, taking possession of Château in 1570. Another literary accomplishment of Montaigne, before the publication of his Essays, was a posthumous edition of his friend Boétie's works, which he helped see to publication.

In 1571, Montaigne retired from public life to the Tower of the Château, Montaigne's so-called "citadelle," where he almost totally isolated himself from every social (and familiar) affair. Locked up in his vast library he began work on his Essays, first published in 1580. On the day of his 38th birthday, as he entered this almost ten-year isolation period, he let the following inscription crown the bookshelves of his working chamber:

|

An. Christi 1571 aet. 38, pridie cal. cart., die suo natali, Mich. Montanus, servitii aulici et munerum publicorum jamdudum pertaesus, dum se integer in doctarum virginum recessit sinus, ubi quietus et omnium securus quantillum in tandem superabit decursi multa jam plus parte spatii; si modo fata duint exigat istas sedes et dulces latebras, avitasque, libertati suae, tranquillitatique, et otio consecravit. |

In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michel de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares be will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure. |

During this time of the Wars of Religion, Montaigne, himself a Roman Catholic, acted as a mediating force, respected both by the Catholic Henry III and the Protestant Henry of Navarre.

In 1578, Montaigne, whose health had always been excellent, started suffering from painful kidney stones, a sickness he had inherited from his father's family. From 1580 to 1581, Montaigne traveled in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Italy, partly in search of a cure. He kept a detailed journal recording various episodes and regional differences. It was published much later, in 1774, under the title Travel Journal. While in Rome in 1581, Montaigne learned that he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux; he returned and served until 1585, again mediating between Catholics and Protestants. His eloquence as a statesman and his ability to successfully negotiate between the warring Catholic and Protestant factions earned Montaigne a great deal of respect throughout France, and for most of his life he would be remembered for his excellence as a politician even more than for his writings.

Montaigne continued to extend, revise and oversee the publication of his Essays. In 1588 he met the writer, Marie de Gournay, who admired his work and would later edit and publish it. King Henry III was assassinated in 1589, and Montaigne then helped to keep Bordeaux loyal to Henry of Navarre, who would go on to become King Henry IV.

Montaigne died in 1592 at the Château de Montaigne and was buried nearby. Later his remains were moved to the Church of St. Antoine at Bordeaux. The church no longer exists: it became the Convent des Feuillants, which has also been lost. The Bordeaux Tourist Office says that Montaigne is buried at the Musée Aquitaine, Faculté des Lettres, Université Bordeaux 3 Michel de Montaigne, Pessac. His heart is preserved in the parish church of Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, near his native land.

The Essais

The Essais—translated literally from the French as "trials" or "attempts"—are Montaigne's magnum opus, and one of the most important single pieces of literature written during the French Renaissance. The Essais, as is clear even from their title, are remarkable for the humility of Montaigne's approach. Montaigne always makes it clear that he is only attempting to uncover the truth, and that his readers should always attempt to test his conclusions for themselves. Montaigne's essays, in their very form, are one of the highest testaments to the humanist philosophy to which Montaigne himself owed so much of his thought; honest, humble, and always open to taking in ideas from any source, the Essais are one of the first truly humane works of literature—literature written truly written for the sake of everyman.

The Essais consist of a collection of a large number of short subjective treatments of various topics. Montaigne's stated goal is to describe man, and especially himself, with utter frankness. He finds the great variety and volatility of human nature to be its most basic features. Among the topics he addresses include descriptions of own poor memory, his ability to solve problems and mediate conflicts without truly getting emotionally involved, his disdain for man's pursuit of lasting fame, and his attempts to detach himself from worldly things to prepare for death; among these more philosophical topics there are also interspersed essays on lighter subjects, such as diet and gastronomy, and the enjoyments to be found in taking a walk through the countryside.

One of the primary themes that emerges in the Essais is Montaigne's deep distrust of dogmatic thinking. He rejects the belief in dogma for dogma's sake, stressing that one must always be skeptical and analytical so as to be able to tell the difference between what is true and what is not. His skepticism is best expressed in the long essay "An Apology for Raymond Sebond" (Book 2, Chapter 12) which has frequently been published separately. In the "Apology," Montaigne argues that we cannot trust our reasoning because thoughts just occur to us; we don't truly control them. We do not, he argues strongly, have good reasons to consider ourselves superior to the animals. Throughout the "Apology" Montaigne repeats the question "What do I know?." He addresses the epistemological question: what is it possible for one to know, and how can you be really sure that you know what you think you know? The question, and its implications, have become a sort of motto for Montaigne; at bottom, all of the Essais are concerned with the epistemological problem of how one obtains knowledge. Montaigne's approach is a simple one, yet it is remarkably effective and remains refreshingly new: all the subject can ever be certain of is what comes from the subject; therefore, Montaigne attempts in essay after essay to begin from his own observations—it is only through utmost concentration beginning from ones own thoughts and perceptions that any truth can ever arrive.

This attitude, for which Montaigne received much criticism in his own time, has become one of the defining principles of The Enlightenment and Montaigne's ideas, as well as his forthright style, would have a tremendous influence on essayists and writers of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries the world over.

Related writers and influence

Among the thinkers exploring similar ideas, one can mention Erasmus, Thomas More, and Guillaume Budé, all working about 50 years before Montaigne.

Montaigne's book of essays is one of the few books that scholars can confirm Shakespeare had in his library, and his great essay "On Cannibals" is seen as a direct source for "The Tempest."

Much of Blaise Pascal's skepticism in his Pensées was a result of reading Montaigne, and his influence is also seen in the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Friedrich Nietzsche was moved to judge of Montaigne: "That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this Earth." (from "Schopenhauer as Educator")

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Works by Michel de Montaigne. Project Gutenberg

- Charles Cotton translation of some of Montaigne's essays Project Gutenberg

- Photos of his chateau, his personal belongings, and a memorial The photograph described as 'Montaigne's grave' is actually a memorial outside the parish church at St Michel de Montaigne, where his heart is preserved.

- Montaigne ein freier mensch (German)

- Biographie et citations de Montaigne (French)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.