| Mi'kmaq |

|---|

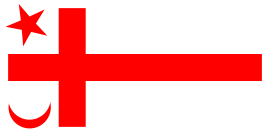

| Míkmaq State flag |

| Total population |

| 40,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec), United States (Maine) |

| Languages |

| English, Míkmaq, French |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Algonquian peoples |

The Mi'kmaq ([miňźgma…£]; (also spelled M√≠kmaq, Mi'gmaq, Micmac or MicMac) are a First Nations/Native American people, indigenous to northeastern New England, Canada's Atlantic Provinces, and the Gasp√© Peninsula of Quebec. The word M√≠kmaw is an adjectival form of the plural noun for the people, M√≠kmaq. Mi'kmaq are self-recognized as L'nu (in the singular; the plural is Lnu'k). The name Mi'kmaq comes from a word in their language meaning "allies."

Although early reports made the Micmac appear fierce and warlike, they were early to adopt Christian teachings from the Jesuits. They allied and inter-married with the French against the British. As with many Native Americans, their numbers were drastically reduced by European borne disease, although contemporary Micmac, many of whom have mixed blood, have increased in number. A substantial number still speak the Algonquian language, which was once written in Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing and is now written using most letters of the standard Latin alphabet.

The Micmac continue to be a peaceful and welcoming people. Their annual Pow-wows are held not only to bring unity to the Micmac nation, and spread cultural awareness through traditional rituals, but they are also open to the public. The Micmac still produce a variety of traditional baskets made of splint ash wood, birch bark, and split cedar, which they sell for revenue to help sustain their culture. They are famous for their cedar and birch boxes, adorned with porcupine quills. In these ways, the Micmac strive to maintain their cultural identity and traditions, while continuing and building greater harmony with others.

Introduction

Members of the Mi'kmaq First Nation historically referred to themselves as L'nu, meaning human being.[1] But, the Mi'kmaq's French allies, whom the Mi'kmaq referred to as Ni'kmaq, meaning "my kin," initially referred to the Mi'kmaq, (as is written in Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France) as "Souriquois" (the Souricoua River was a travel route between the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence) or "Gaspesians." Over time their French allies and succeeding immigrating nations’ peoples began to refer to the Lnu'k as Ni’knaq, (invariably corrupting the word to various spellings such as Mik Mak and Mic Mac) The British originally referred to them as Tarrantines.[2]

With constant use, the term "Micmac" entered the English lexicon, and was used by the Lnu'k as well. Present day Lnu’k linguists have standardized the writing of Lnui'simk for modern times and "Mi’kmaq" is now the official spelling of the name. The name "Quebec" is thought to derive from a Mi'kmaq word meaning "strait," referring to the narrow channel of the Saint Lawrence River near the city site.

The pre-contact Mi'kmaq population is estimated at 35,000. In 1616 Father Biard believed the Mi'kmaq population to be in excess of 3,000. But he remarked that, because of European diseases, there had been large population losses in the last century. Smallpox, wars, and alcoholism led to a further decline of the native population, which was probably at its lowest in the middle of the seventeenth century. Then the numbers grew slightly again and seemed to be stable during the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century the population was on the rise again. The average annual growth from 1965 to 1970 was about 2.5 percent, and has been steadily on the rise ever since. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, population estimates were around 40,000.

History

The ancestors of the Micmac came to occupy their traditional home lands through immigration. It is speculated that the Paleo-Indians came into the area we now know as Nova Scotia around 11,000 years ago. They came over from Asia via Siberia, and over time spread south and east nomadically. The Micmac were of a milder temperament than the infamous Mohawk and Iroquois, and dealing with the pressure of fiercer ethnic tribes from their southern neighbors, they were pushed to the northeastern extremities of the continent.

The Mi'kmaq were members of the Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki Confederacy), an alliance with four other Algonquin nations: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. At the time of contact with the French (late 1500s) they were expanding from their Maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /Saint Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquioian Mohawk tribes, hence the Mi'kmaq name for this peninsula, Gespedeg ("last-acquired").

In 1610, Chief Membertou concluded their first alliance with Europeans, a concordat with the French Jesuits that affirmed the right of Mi'kmaq to choose Catholicism, Mi'kmaq tradition, or both.

Henri Membertou (died September 18, 1611) was the sakmow (Grand Chief) of the Mi'kmaq tribe situated near Port Royal, site of the first French settlement in Acadia, present-day Nova Scotia, Canada. Originally sakmow of the Kespukwitk district, he was appointed as Grand Chief by the sakmowk of the other six districts. His exact date of birth is not known. However, Membertou claimed to be a grown man when he first met Jacques Cartier.[3]

Membertou was the leader of a small band of Mi'kmaq whose hunting and fishing territory included the area of Port-Royal.[3] In addition to being sakmow or political leader, Membertou had also been the head autmoin or spiritual leader of his tribe ‚ÄĒ who believed him to have powers of healing and prophecy. He first met the French when they arrived to build the Habitation at Port-Royal in 1605, at which time, according to the French lawyer and author Marc Lescarbot, he said he was over 100 and recalled meeting Jacques Cartier in 1534. Membertou became a good friend to the French. Father Biard described him as being tall and large limbed compared to the other natives. It is also said that he had a beard in contrast to the others who removed any facial hair.[3] Also, unlike most sakmowk who were polygamous, Membertou had only one wife, who was baptized with the name of "Marie."

After building their fort, the French left in 1607, leaving only two of their party behind, during which time Membertou took good care of the fort and them, meeting them upon their return in 1610. On June 24th 1610 (Saint John the Baptist Day), Membertou became the first Aboriginal to be baptized in New France. The ceremony was carried out by priest Jessé Fléché. He had just arrived from New France and he went on to baptize all of Membertou's immediate family. However, there was no proper preparation due to the fact that priest Jessé Fléché did not speak the Algonquian language and on their part, the Mi'kmaq did not speak much French. It was then that Membertou was given the baptized name of the late king of France, Henri, as a sign of alliance and good faith.[3]

Membertou was very eager to become a proper Christian as soon as he was baptized. He wanted the missionaries to learn the Algonquian language so that he could be properly educated.[3] Biard relates how, when Membertou's son Actaudin became gravely ill, he was prepared to sacrifice two or three dogs to precede him as messengers into the spirit world, but when Biard told him this was wrong, he did not, and Actaudin then recovered. However, in 1611, Membertou contracted dysentery, which is one of the many infectious diseases that was brought and spread in the New World by the Europeans. By September 1611, he was very ill. Membertou insisted on being buried with his ancestors, something that bothered the missionaries. Finally, Membertou changed his mind and requested to be buried among the French.[3] In his final words he charged his children to remain devout Christians.

The last year of Membertou's life shows a pattern that emerged among the indigenous people that were "Christianized" by European missionaries. They did not understand the principles of Christianity thus they could hardly have been said to be converted. They often died shortly after they were baptized, usually dying from the contagious diseases that were introduced by the missionaries themselves.[3]

The Mi'kmaq were allies with the French, and were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst. But as France lost control of Acadia in the early 1700s, they soon found themselves overwhelmed by British (English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh) who seized much of the land without payment and deported the French. Between 1725 and 1779, the Mi'kmaq signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with Great Britain, but none of these were land cession treaties. The nation historically consisted of seven districts, but this was later expanded to eight with the ceremonial addition of Great Britain at the time of the 1749 treaty. Later on the Mi'kmaq also settled Newfoundland as the unrelated Beothuk tribe became extinct. Mi'kmaq representatives also concluded the first international treaty with the United States after its declaration of independence, the Treaty of Watertown.

Culture

The Micmac were a migratory people, who would live in the woods during winter months hunting large game like moose and porcupine, while moving to the seashore during the spring where they would switch to a heavy seafood diet. They adapted well to the heavy winter hunting expeditions, often overwhelming caribou that would get stuck in deep snow as the Micmac would trudge through on top of the frozen snow with their snowshoes. Agriculture was not as abundant in the north, and many Micmac would sustain themselves through roots, herbs, and meats.

Their material possessions were few and far between, and out of necessity, practical items such as hunting and farming tools. They lived in single family dome-shaped lodges, known as wigwams. These were constructed out of young pine or spruce saplings, stripped of bark, and covered with bands of flexible hard wood, which tied skins and hides together to form thatched roofs.

The tribal rulers were all male over the age of 25. The most successful hunter and provider of food for his family, the extended family, and the tribe, were made chiefs. Chiefdom was semi-hereditary, passed on throughout generations, although young Micmac braves could always become a chief in their own right, with enough conquests.

Religion

The Micmac recognized a Great Spirit called Manitou and even several lesser spirits, also called Manitous - in Micmac Mento, or Minto- and they had no other personal divinities. They feared and revered Manitou while offering sacrifices, thus enabling him. Seeking to render him with a favorable blessing, or rather to prevent his wrath in their various enterprises, they would often sacrifice small animals. A dog was generally regarded as the most valuable sacrifice. If they were crossing a lake and their canoe was in danger of being overwhelmed by wind and water, a dog was often thrown overboard with its forepaws tied together, in order to satisfy the wrath of the angry Manitou.

The Micmac were highly superstitious, and they were continually on the watch for omens and ill harbingers, which would easily deter from any activity that was considered unfavorable by Manitou. For example, a hunter would turn away from prime hunting conditions if he heard a cry of a certain animal, such as the spotted owl.

The Micmac did believe in creation and recognized a higher power as controlling their collective and individual destinies; a power that was entitled to reverence. These beliefs were apparent in many Native American tribes. The European missionaries were very eager to convert them to their own Christian religion, and somewhat successful at times.

Marc Lescarbot, in 1606, quoted Jacques Cartier, who had been in the territory 65 years earlier, as noting about their religious beliefs:

They believe also that when they die they go up into the stars, and afterwards they go into fair green fields, full of fair trees, flowers, and rare fruits. After they had made us to understand these things, we showed them their error, and that their Cudouagni is an evil spirit that deceiveth them, and that there is but one God, which is in Heaven, who doth give unto us all, and is Creator of all things, and that in him we must only believe, and that they must be baptized, or go into hell. And many other things of our faith were showed them, which they easily believed, and called their Cudouagni, Agoiuda.[4]

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing was a pictographic writing scheme and memory aid used by the Mi'kmaq. Technically, the Mi'kmaq system was logographic rather than hieroglyphic, because hieroglyphs incorporate both alphabetic and logographic information. The Mi'kmaq system was entirely logographic.

It has been debated by some scholars whether the original "hieroglyphs" qualified fully as a writing system rather than merely a mnemonic device, before their adaptation for pedagogical purposes in the seventeenth century by the French missionary Chrétien Le Clercq. Ives Goddard, and William Fitzhugh from the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution contended in 1978 that the system was purely mnemonic, because it could not be used to write new compositions. Schmidt and Marshall argued in 1995 that the newly adapted form was able to act as a fully-functional writing system, and did not involve only mnemonic functions. This would mean that the Mi'kmaq system is the oldest writing system for a North American language north of Mexico.

Father le Clercq, a Roman Catholic missionary on the Gaspé Peninsula from 1675, claimed that he had seen some Mi'kmaq children 'writing' symbols on birchbark as a memory aid. This was sometimes done by pressing porcupine quills directly into the bark in the shape of symbols. Le Clercq adapted those symbols to writing prayers, developing new symbols as necessary. This writing system proved popular among Mi'kmaq, and was still in use in the nineteenth century. Since there is no historical or archaeological evidence of these symbols from before the arrival of this missionary, it is unclear how ancient the use of the mnemonic glyphs was. The relationship of these symbols with Mi'kmaq petroglyphs is also unclear.

Contemporary

The Micmac Nation currently has a population of about 40,000 of whom approximately one-third still speak the Algonquian language Lnuísimk which was once written in Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing and is now written using mostly letters of the standard Latin alphabet.

The Micmac still produce a variety of traditional baskets made of splint ash wood, birch bark and split cedar, which they sell for revenue to help sustain their culture. They are also famous for their cedar and birch boxes, adorned with porcupine quills.

After much political lobbying, on November 26, 1991, the Aroostook Band of Micmacs finally achieved Federal Recognition with the passage of the Aroostook Band of Micmacs Settlement Act. This act provided the Community with acknowledgment of its tribal status in the United States, and consequently The Aroostook Band of Micmacs have succeeded in rejuvenating a large part of the Micmac Nation through this political movement.

The spiritual capital of the Mi'kmaq nation is the gathering place of the Mi'kmaq Grand Council, Mniku or Chapel Island in the Bras d'Or Lakes of Cape Breton Island. The island also the site of the St. Anne Mission, an important pilgrimage site for the Mi'kmaq. The island has been declared a historic site.

In the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador October is celebrated as Mi'kmaq History Month and the entire Nation celebrates Treaty Day annually on October 1st.

An annual Pow wow is held during the month of August in Scotchfort, on Prince Edward Island in order to bring unity to the Micmac nation, and spread cultural awareness through traditional rituals. It is not a celebration exclusive to the Micmac only, but open to the public, and encourages people from all nationalities to participate. They continue to be a peaceful and welcoming people.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ The Nova Scotia Museum Mi'kmaq Portraits database.

- ‚ÜĎ Lydia Affleck and Simon White. "A Circle of Friends Interview with Barbara Bernard" "Our Language" Native Traditions [1] accessdate 2006-11-08

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 J. M. Bumsted. A History of the Canadian Peoples. (Canada: Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 0195423496)

- ‚ÜĎ History of Nova Scotia "The Micmac of Megumaagee" Retrieved December 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bock, Philip K. "Micmac." 109-122. In Bruce G. Trigger (ed.) Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0160045752

- Bumsted, J. M. A History of the Canadian Peoples. Canada: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0195423496

- Chaisson, Paul. The Island of Seven Cities: Where the Chinese Settled when they Discovered North America. Random House Canada, 2007, 170. ISBN 978-0679314561

- Choyce, Lesley. The Mi'kmaq Anthology. Nimbus Publishing (CN), 2005. ISBN 1895900042

- Davis, Stephen A. Mi'kmaq: Peoples of the Maritimes. Nimbus Publishing, 1997. 978-1551091808

- Fell, Barry. "The Micmac Manuscripts" in Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, 21 (1992): 295.

- Goddard, Ives and William W. Fitzhugh. "Barry Fell Reexamined," in The Biblical Archaeologist 41(3) (September 1978): 85-88.

- Kauder, Christian. Sapeoig Oigatigen tan teli G√īmgoetjoigasigel Alasotmaganel, Ginamatineoel ag Getapefiemgeoel; Manuel de Pri√®res, instructions et changs sacr√©s en Hieroglyphes micmacs; Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms & Hymns in Micmac Ideograms. New edition of Father Kauder's Book published in 1866. Ristigouche, Qu√©bec: The Micmac Messenger, 1921.

- Lenhart, John. History relating to Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms and Hymns in Micmac Ideograms used by Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. Sydney, Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Native Communications Society.

- Lescarbot, Marc. Nova Francia: A Description of Acadia, 1606. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0415344685

- Paul, Daniel N. We Were Not the Savages: A Mi'kmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations. Fernwood Publishing Co., 2007. ISBN 978-1552662090

- Prins, Harald E. L. The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology). Wadsworth, 1996. ISBN 978-0030534270

- Schmidt, David L., and B. A. Balcom. "The Règlements of 1739: A Note on Micmac Law and Literacy," in Acadiensis XXIII, 1 (Autumn 1993): 110-127. ISSN 0044-5851

- Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. Mi'kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing, 1995. ISBN 1551090694

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Whitehead, Ruth Holmes. The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Mi'kmaq History 1500-1950. Nimbus Pub Ltd, 2004. ISBN 0921054831

- Wicken, William C. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0802076656

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Micmac History

- Mi'kmaq Dictionary Online

- The Micmac of Megumaagee

- Micmac Indian Tribe History

- Biography of Henri Membertou Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.