Moai

Moai, or mo‘ai, are monolithic human figures carved from rock on the Chilean Polynesian island of Easter Island between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the island's perimeter. Almost all moai have overly large heads three-fifths the size of their bodies.

Moai must have been extremely expensive to craft and transport; not only would the actual carving of each statue require effort and resources, but many of the finished statues were then hauled to their final location and erected. The motivation for creating these monumental works of art and the techniques used to carve and transport them have fascinated scholars and the general public alike for centuries.

Description

The moai are monolithic statues, their minimalist style related to, yet distinct from, forms found throughout Polynesia. The society of Polynesian origin that settled on Rapa Nui around 300 C.E. established a unique, imaginative tradition of monumental sculpture that built shrines and erected the enormous stone moai that have fascinated people from other cultures ever since.[1]

Moai were carved in relatively flat planes, the faces bearing proud but enigmatic expressions. The over-large heads (a three-to-five ratio between the head and the body, a sculptural trait that demonstrates the Polynesian belief in the sanctity of the chiefly head) have heavy brows and elongated noses with a distinctive fish-hook-shaped curl of the nostrils. The lips protrude in a thin pout. Like the nose, the ears are elongated and oblong in form. The jaw lines stand out against the truncated neck. The torsos are heavy and, sometimes, the clavicles are subtly outlined in stone. The arms are carved in bas relief and rest against the body in various positions, hands and long slender fingers resting along the crests of the hips, meeting at the hami (loincloth), with the thumbs sometimes pointing towards the navel. Generally, the anatomical features of the backs are not detailed, but sometimes bear a ring and girdle motif on the buttocks and lower back. Except for one kneeling moai, the statues do not have legs.

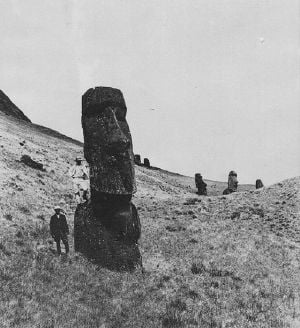

Although moai are whole-body statues, they are commonly referred to as "Easter Island heads." This is partly because of the disproportionate size of their heads and partly because for many years the only moai standing on the island were the statues on the slopes of Rano Raraku, most of which are buried to their shoulders. Some of the "heads" at Rano Raraku have since been excavated, revealing their bodies which have markings that had been protected from erosion by their burial.

History

The statues were carved by the Polynesian colonizers of the island, mostly between circa 1250 C.E. and 1500 C.E.[2] The island was first discovered by Europeans on Easter Sunday 1722, when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen encountered 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants on the island. The name "Easter Island" stems from this first European contact. Most of the moai were still standing when Roggeveen arrived.

1722–1868 toppling of the moai

In the years after the Roggeveen visit, several other explorers visited the island. During this period all of the moai that had been erected on ahu were toppled. In 1774, British explorer James Cook visited Easter Island and reported that some statues had fallen over. William Hodges, Cook's artist, produced an oil painting of the island showing a number of moai, some of them with hat-shaped stone pukao ("topknots"). Hodges depicted most of the moai standing upright on ahu.[3]

With the adoption of Christianity in the 1860s, the remaining standing moai were toppled. The last standing statues were reported in 1838 by Abel Aubert Dupetit Thouars, and no upright statues by 1868,[4] apart from the partially buried ones on the outer slopes of Rano Raraku.

Oral histories indicate that the toppling of the moai was part of a deadly conflict among the islanders, rather than an earthquake or other cause. Most of the moai were toppled forward to where their faces were hidden and often were toppled in such a way that their necks broke. Today, about 50 moai have been re-erected on their ahu or in museums elsewhere.

Removal

Since the removal of the first moai, Hoa Hakananai'a, from Easter Island in 1869 by the crew of HMS Topaze, 79 complete moai, heads, torsos, pukao, and moai figurines are also known to have been removed from their original sites, and transferred to either private collections, the collections of museums (including the Museo Arqueological Padre Sebastian Englert on Easter Island,[5] the Otago Museum in New Zealand,[6] and the British Museum in London[3]), and one was presented as a gift to the American University, Washington D.C. in 2000.[7] Some of the moai have been further transferred between museums and private collections, for reasons such as preservation, academic research, and for public education, or—in the instance of the moai from Centro Cultural Recoleta—for repatriation after 80 years overseas.[8]

Construction

The production and transportation of the 887 known monolithic statues are considered remarkable creative and physical feats.[9]

All but 53 of the 887 moai known to date were carved from tuff (a compressed volcanic ash), using a single piece of rock. There are also 13 moai carved from basalt, 22 from trachyte, and 17 from fragile red scoria.[10]

Many of the moai were transported to and installed on an ahu—a stone pedestal upon which several moai were mounted, facing inland across the island. However, a larger proportion were found still in the Rano Raraku quarry (397 moai); 288 were successfully transported to a variety of ahu; and 92 have been located somewhere outside of the quarry area, apparently in transit to an ahu.[10]

Moai range in size from a height of less than 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) to around 10 meters (33 ft) tall. The tallest moai erected, called Paro, was 9.2 meters (30 ft) high and weighed 82 tons; the largest that fell while being erected was 9.94 meters (32.6 ft); and the largest (unfinished) moai, found at the Rano Raraku Quarry and named El Gigante, would have been 21.6 meters (71 ft) tall with a weight of about 150 tons.[11]

Easter Island moai are known for their large, broad noses and strong chins, along with rectangle-shaped ears and deep eye slits.

Eyes

In 1979, Sergio Rapu Haoa and a team of archaeologists collected and reassembled broken fragments of white coral that were found at the various ahu sites. They discovered that the hemispherical or deep elliptical eye sockets were designed to hold coral eyes with either black obsidian or red scoria pupils. Subsequently, previously uncategorized finds in the Easter Island museum were re-examined and categorized as eye fragments. It is thought that the moai with carved eye sockets were probably allocated to the ahu and ceremonial sites, with the eyes being inserted after the moai were installed on the ahu.

Pukao topknots and headdresses

Pukao are the hats or "topknots" formerly placed on top of some moai statues that had been erected on ahu. The pukao were all carved from a very light red volcanic stone, scoria, which was quarried from a single source at Puna Pau.

Pukao are cylindrical in shape with a dent on the underside to fit on the head of the moai and a boss or knot on top. They fitted onto the moai in such a way that the pukao protruded forwards. Their size varies in proportion to the moai they were on, but they can be up to eight feet tall and eight feet in diameter. Pukao may have represented dressed hair or headdresses of red feathers worn by chiefs throughout Polynesia.

It is not known how they were raised and placed on the heads of the moai, but theories include them being raised with the statue or placed after the statue was erected. After the Pukao were made in the quarry, they were rolled by hand or on tree logs to the site of the statues along an ancient road. The road was built out of a cement of compressed red scoria dust. Over 70 discarded Pukao have been found along the road and on raised ceremonial platforms.[12]

Markings (post stone working)

When first carved, the surface of the moai was polished smooth by rubbing with pumice. Unfortunately, the easily worked tuff from which most moai were carved is also easily eroded, and, today, the best place to see the surface detail is on the few moai carved from basalt or in photographs and other archaeological records of moai surfaces protected by burial.

The moai that are less eroded typically have designs carved on their backs and posteriors. The Routledge expedition of 1914 established a cultural link between these designs and the island's traditional tattooing, which had been repressed by missionaries a half-century earlier.[13]

At least some of the moai were painted; Hoa Hakananai'a was decorated with maroon and white paint until 1868, when it was removed from the island.

Special moai

- Hoa Hakananai'a

Hoa Hakananai'a is housed in the British Museum in London. The name Hoa hakanani'a is from the Rapa Nui language; it means (roughly) "stolen or hidden friend."[14] It was removed[5] from Orongo, Easter Island on 7 November 1868 by the crew of the English ship HMS Topaze, and arrived in Portsmouth on 25 August 1869.[14]

Whilst most moai were carved from easily worked tuff, Hoa Hakananai'a is one of just sixteen moai that were carved from much harder basalt.[14] It is 55 centimeters from front to back, 2.42 meters high and weighs "around four tons."[3]

Hoa Hakananai'a has an overly large head, which is typical for moai. Originally the empty eye sockets would have had coral and obsidian eyeballs, and the body was painted red and white. However, the paint was washed off during its removal from the island.

Due to the fact that it is made of basalt, and it was removed to the British Museum, this statue is better preserved than the majority of those made of tuff that remained exposed on Rapa Nui and suffered erosion. Hoa Hakananai'a has a maro carving around its waist. This is a symbolic loincloth of three raised bands, topped (at the back) by a ring of stone just touching the top band.

Its back is richly decorated with carvings related to the island's Birdman cult. These include two birdmen with human hands and feet, but with frigatebird heads, said by the Rapa Nui people to suggest a family or sexual relationship. Above these is a fledgling with its beak open. These carvings on the back of the statue are actually re-carvings, created some time after the moai's original creation. They are similar to the Birdman petroglyphs at Orongo on Easter Island, which relate to the Manutara, a Sooty tern which heralded the annual return of the god Make-make. Hoa Hakananai'a is a clear link between the two artistic traditions—the moai statues and the petroglyphs—and thus between the religious traditions of the moai and the Birdman cult.[9]

- Tukuturi

Tukuturi is an unusual moai, being the only statue with legs. Its beard and kneeling posture also distinguish it from other moai.

Tukuturi is made of red scoria from Puna Pau, but sits at Rano Raraku, the tuff quarry. It is possibly related to the Tangata manu cult, in which case it would be one of the last moai created.[10]

Craftsmen

The moai were not carved by slaves or workers under duress, but by master craftsmen, formed into guilds, and highly honored for their skills. The oral histories show that the Rano Raraku quarry which supplied the stone for almost all the moai was subdivided into different territories for each clan.

Rano Raraku

Rano Raraku is a volcanic crater formed of consolidated volcanic ash, or tuff, and located on the lower slopes of Terevaka in the Rapa Nui National Park on Easter Island. It was a quarry for about 500 years until the early eighteenth century, and supplied the stone from which about 95 percent of the island's known moai were carved. Rano Raraku is a visual record of moai design vocabulary and technological innovation; almost 400 moai remain in or close to the quarry.

The incomplete statues in the quarry are remarkable both for their number, for the inaccessibility of some that were high on the outside crater wall and for the size of the largest; at 21.6 m (71 feet) in height, almost twice that of any moai ever completed and weighing an estimated 150 tons, many times the weight of any transported.

Some of the incomplete moai seem to have been abandoned after the carvers encountered inclusions of very hard rock in the material. Others may be sculptures that were never intended to be separated from the rock in which they are carved.

On the outside of the quarry are a number of moai, some of which are partially buried to their shoulders in the spoil from the quarry. They are distinctive in that their eyes were not hollowed out, they do not have Pukao, and they were not cast down when the moai standing on ahu were toppled. For this last reason, they supplied some of the most famous images of the island.

The quarries in Rano Raraku appear to have been abandoned abruptly, with a litter of stone tools; many completed moai remain outside the quarry awaiting transport and almost as many incomplete statues are still in situ as were installed on ahu. While this situation initially posed yet another mystery regarding the moai, it has been concluded that:

- Some statues were rock carvings and never intended to be completed.

- Some were incomplete because, when inclusions of hard rock were encountered the carvers abandoned a partial statue and started a new one[13]

- Some completed statues at Rano Raraku were placed there permanently and not parked temporarily awaiting removal.[13]

- Some moai were indeed incomplete when the statue-building era came to an end.

Purpose

The moai stood on an ahu as representatives of sacred chiefs and gods. In addition to representing deceased ancestors, the moai, once they were erected on ahu, may also have been regarded as the embodiment of powerful living or former chiefs and important lineage status symbols.

According to archaeologist Jo Anne Van Tilburg, who has studied the moai for many years and is director of the Easter Island Statue Project,[15] the moai statues were not individual portraits but rather standardized representations of powerful individuals or chiefs. She has also suggested that their role was both secular and sacred, mediators between the chiefs and their people, and between the chiefs and the gods.[11]

Ahu

Ahu are stone platforms upon which one or more moai stand. They are situated on bluffs and in areas commanding a view of the sea. Each ahu was constructed of neatly fitted stone blocks set without mortar. The platform generally supported four to six moai, although one ahu, known as Tongariki, carried 15 moai. Within many of the ahu, vaults house individual or group burials.

The ahu of Easter Island are related to the traditional Polynesian marae—a traditional place which serves religious and social purposes. The marae generally consists of an area of cleared land (the marae itself), bordered with stones or wooden posts and in some cases, a central stone ahu. In the Rapanui culture ahu has become a synonym for the whole marae complex. Ahu are similar to structures found in the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, where upright stone slabs stood for chiefs. When a chief died, his stone remained.

The classic elements of ahu design are:

- A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea

- A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs called paenga

- A facia made of red scoria that went over the front wall (platforms built after 1300)

- A sloping ramp in the inland part of the platform, extending outward like wings

- A pavement of even–sized, round water–worn stones called poro

- An alignment of stones before the ramp

- A paved plaza before the ahu. This was called marae

- Inside the ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many ahu would have been:

- Moai on squarish "pedestals" looking inland, the ramp with the poro before them.

- Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau on the moai heads (platforms built after 1300).

- When a ceremony took place, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The whites of the eyes were made of coral, the iris was made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu are on average 1.25 meters (4.1 ft) high. The largest ahu is 220 meters (720 ft) long and holds 15 statues, some of which are 9 meters (30 ft) high.

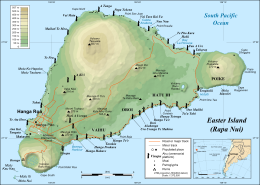

Ahu are found mostly on the coast, where they are distributed fairly evenly except on the western slopes of Mount Terevaka and the Rano Kau and Poike headlands. One ahu with several moai was recorded on the cliffs at Rano Kau in the 1880s, but had fallen to the beach before the Routledge expedition.[13]

Varying greatly in layout, many ahu were reworked during or after the huri mo'ai or statue–toppling era; many became burial sites; and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami. Ahu Tongariki, one kilometer from Rano Raraku, had the most moai, 15 in total. Another notable ahu with moai is Ahu Akivi, restored in 1960 by William Mulloy.

Ahu Tongariki

Ahu Tongariki is the largest ahu on Easter Island. Its moai were toppled during the statue toppling period and in 1960 the ahu was swept inland by a tsunami.

Ahu Tongariki was substantially restored in the 1990s by a multidisciplinary team headed by archaeologists Claudio Cristino and Patricia Vargas, in a five year project carried out under an official agreement of the Chilean Government with the University of Chile. It now has fifteen moai, including an 150 ton moai that was the heaviest ever erected on the island. All the moai face sunset during the summer solstice.

Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi is an ahu with seven moai. The ahu and its moai were restored in 1960 by the American archaeologist William Mulloy and his Chilean colleague, Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro. Mulloy's work on the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex was supported by the Fulbright Foundation and by grants from the University of Wyoming, the University of Chile and the International Fund for Monuments.

The Moai face sunset during the spring and autumn equinox, with their backs to the sunrise.

Unlike other ahu, the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex is not located on the coast. In contrast to those at other sites on the island, the moai at Ahu Akivi face the ocean.

Transportation

Since Easter Island was treeless by the time the Europeans first visited, the movement of the statues was a mystery for many years. Oral histories recount how various people used divine power to command the statues to walk. The earliest accounts say a king named Tuu Ku Ihu moved them with the help of the god Makemake, while later stories tell of a woman who lived alone on the mountain ordering them about at her will.

It is not known exactly how the moai were moved across the island, but the process almost certainly required human energy, ropes, and possibly wooden sledges (sleds) and/or rollers, as well as leveled tracks across the island (the Easter Island roads). Pollen analysis has now established that the island was almost totally forested until 1200 C.E. The tree pollen disappeared from the record by 1650 C.E., which roughly coincides with the time the statues stopped being made.

Scholars currently support the theory that the main method was that the moai were "walked" upright (some assume by a rocking process), as laying them prone on a sledge (the method used by the Easter Islanders to move stone in the 1860s) would have required an estimated 1500 people to move the largest moai that had been successfully erected. Thor Heyerdahl had tried pulling a smaller statue on its back in 1956; it took 180 people to move it a short distance.[16]

Czech engineer Pavel Pavel came up with a scheme to make moai "walk" across the ground. By fastening ropes around a model they were able to move it forward by twisting and tilting it. This method required only 17 people to make it "walk."[17]

In 1986, Thor Heyerdahl invited Pavel Pavel to join him on a return expedition to Easter Island, where they tried his technique of "walking" moai. They experimented with a five-ton moai and a nine-ton moai. With a rope around the head of the statue and another around the base, using eight workers for the smaller statue and 16 for the larger, they "walked" the moai forward by swiveling and rocking them from side to side. However, the experiment was ended early due to damage to the statue bases from chipping. Despite the early end to the experiment, Heyerdahl estimated that this method for a 20-ton statue over Easter Island terrain would allow 320 feet (100 m) per day.[18]

Archaeologist Charles Love experimented with a ten-ton replica. His first experiment found rocking the statue to walk it was too unstable over more than a few hundred yards. He then found that placing the statue upright on two sled runners atop log rollers, 25 men were able to move the statue 150 feet (46 m) in two minutes.

In 1998, Jo Anne Van Tilburg suggested that placing sleds on lubricated rollers would greatly reduce the number of people required to move the statues. In 1999, she supervised an experiment to move a nine-ton moai. They attempted to load a replica on a sled built in the shape of an A frame that was placed on rollers. A total of 60 people pulled on several ropes in two attempts to tow the moai. The first attempt failed when the rollers jammed up. The second attempt succeeded when they embedded tracks in the ground, at least across flat ground.

In 2003, further research indicated this method could explain the regularly spaced post holes where the statues were moved over rough ground. Charles Love suggested the holes contained upright posts on either side of the path so that as the statue passed between them, they were used as cantilevers for poles to help push the statue up a slope without the requirement of extra people pulling on the ropes and similarly to slow it on the downward slope. The poles could also act as a brake when needed.[4]

Preservation and restoration

From 1955 through 1978 William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, undertook extensive investigation of the production, transportation, and erection of the moai. Mulloy's Rapa Nui projects include the investigation of the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex and the physical restoration of Ahu Akivi (1960); the investigation and restoration of the Tahai Ceremonial Complex (1970) which includes three ahu: Ko Te Riku (with restored eyes), Tahai, and Vai Ure; the investigation and restoration of two ahu at Hanga Kio'e (1972); the investigation and restoration of the ceremonial village at Orongo (1974) and numerous other archaeological surveys throughout the island. Mulloy's restoration projects earned him the great respect of Rapa Nui islanders, many of whom collaborated with him at multiple venues.

The EISP (Easter Island Statue Project) is the latest research and documentation project of the moai on Rapa Nui and the artifacts held in museums overseas. The purpose of the project is to understand the figures' original use, context, and meaning, with the results being provided to the Rapa Nui families and the island's public agencies that are responsible for conservation and preservation of the moai.[15]

The Rapa Nui National Park and the moai are included on the 1994 list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites and consequently the 1972 UN convention concerning the protection of the world's cultural and natural heritage.

In 2008, a Finnish tourist chipped a piece off the ear of one moai. The tourist was fined $17,000 in damages and was banned from the island for three years.[19]

Gallery of photos

Early European drawing of moai, in the lower half of a 1770 Spanish map of Easter Island

Ahu Tongariki with Poike volcano in the background. The second moai from the right has a pukao on its head

Moai at the Louvre

Notes

- ↑ Rapa Nui National Park, Brief Description Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer, Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island (London: Reaktion Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1861892829).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The British Museum, Hoa Hakananai'a Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 John Flenley and Paul Bahn, The Enigmas of Easter Island (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0192803405).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Remote Possibilities: Hoa Hakananai'a and HMS Topaze on Rapa Nui (British Museum Research Papers, 2006, ISBN 0861591585).

- ↑ The Otago Museum, The Otago Museum Moai Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ American University, American University Dedicates Easter Island Statue American University News. June 2, 2000. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Easter Island statue heads home" The Age (April 18, 2006). Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Hoa Hakananai’a Laser Scan Project Easter Island Statue Project. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture (London: British Museum Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0714125046), 24.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 PBS Nova, Stone Giants Secrets of Easter Island. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Easter Island Red Hat Mystery Revealed Discovery News (Sep 8, 2009). Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Katherine Routledge, The Mystery of Easter Island (1919; New York, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2007, ISBN 978-1602066984).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Hoa Hakananai'a (London: British Museum Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0714150246).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, What is the Easter Island Statue Project? Easter Island Statue Project. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Thor Heyerdahl, Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island (Skokie, IL: Rand McNally & Co., 1958, ISBN 978-0528818103).

- ↑ Pavla Horáková, Czech who made Moai statues walk returns to Easter Island Český rozhlas (20-12-2002). Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Thor Heyerdahl, Easter Island: The Mystery Solved (New York, NY: Random House, 1989, ISBN 978-0394579061).

- ↑ Easter Island fines ear chipper BBC News, April 9, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fischer, Steven Roger (ed.). Easter Island Studies. Oxbow Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0946897605

- Fischer, Steven Roger. Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island. London: Reaktion Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1861892829

- Flenley, John, and Paul Bahn. The Enigmas of Easter Island. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0192803405

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island. Skokie, IL: Rand McNally & Co., 1958. ISBN 978-0528818103

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Easter Island: The Mystery Solved. New York, NY: Random House, 1989. ISBN 978-0394579061

- Hunt, Terry, and Carl Lipo. The Statues that Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. New York, NY: Free Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1439150313

- Matthews, Rupert. Ancient Mysteries (Unexplained). London: QEB Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1595668547

- Metraux, Alfred. Mysteries of Easter Island The Virginia Review of Asian Studies (2003).

- Mulloy, William T. The Easter Island Bulletins of William Mulloy. Cloud Mountain Pub., 1997. ISBN 978-1880636046

- Pelta, Kathy. Rediscovering Easter Island: How History Is Invented. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 978-0822548904

- Peregrine, Peter N., and Melvin Ember (eds.) Encyclopedia of Prehistory, Volume 3: East Asia and Oceania. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2001. ISBN 978-0306462573

- Routledge, Katherine. The Mystery of Easter Island. New York, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2007 (original 1919). ISBN 978-1602066984

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. London: British Museum Press, 1994. ISBN 0714125040

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Hoa Hakananai'a. London: British Museum Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0714150246

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Remote Possibilities: Hoa Hakananai'a and HMS Topaze on Rapa Nui. London: British Museum Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0861591589

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island, Chile) - Britton Shepardson

- Easter Island Statue project

- PBS NOVA: Secrets of Easter Island

- PBS NOVA: Secrets of Lost Empires: Easter Island

- How to make Walking Moai

- History of Easter Island stones

- Father Sebastian Englert Anthropology Museum

- Easter Island Foundation

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Moai history

- Ahu_Tongariki history

- Ahu_Akivi history

- Rano_Raraku history

- Hoa_Hakananai'a history

- Pukao history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.