A longhouse or long house is a type of long, narrow, single-room building built by peoples in various parts of the world. Many were built from timber and represent the earliest form of permanent structure in many cultures. Ruins of prehistoric longhouses have been found in Asia and Europe. Numerous cultures in medieval times built longhouses. Indigenous peoples of the Americas, particularly the Iroquois on the East coast and the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, have significant longhouse traditions which continue to this day.

Longhouses are large structures, built with the materials available in the local environment, that can house multiple families (usually related as an extended family), or a single family with their livestock. Large longhouses can also be used for community gatherings or ceremonies. While the traditional structures were often dark, smoky, and smelly, the design is practical both in physical and social aspects.

The Americas

In North America two types of longhouse were developed: The Native American longhouse of the tribes usually connected with the Iroquois in the northeast, and the type used by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The South American Tucano people also live in multifamily longhouses.

Iroquois and other East Coast longhouses

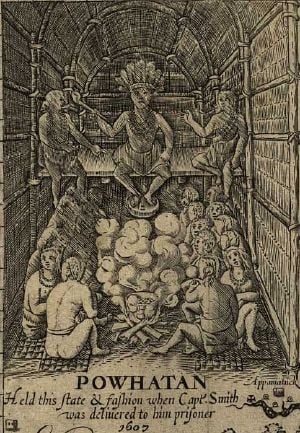

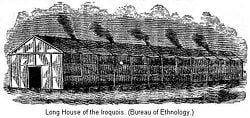

Tribes or ethnic groups in the northeast of North America, south and east of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie that had traditions of building longhouses include the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee which means "people of the longhouse") originally of the Five Nations Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk and later including the Tuscarora. Archaeological evidence shows that Iroquois longhouse construction dates to at least 1100 C.E.[1] Other East Coast tribes that lived in longhouses include the Wyandot and Erie tribes, as well as the Pamunkey in Virginia. Some Algonquian tribes, such as the Lenni Lenape and the Mahican, built longhouses in addition to wigwams, using the longhouses for council meetings.[2]

Longer than they were wide (hence their English name), the Iroquois longhouses had openings at both ends that served as doors and were covered with animal skins during the winter to keep out the cold. A typical longhouse was about 80 feet (24 m) long by 20 feet (6.1 m) wide by 20 feet (6.1 m) high and served as a multi-family dwelling. They might be added to as the extended family grew.

The components for constructing a longhouse were readily available in the forests. Small trees (saplings) with straight trunks were cut and their bark stripped to make the framework for the walls. Strong but flexible trees were used while still green to make the curved rafters. The straight poles were set in the ground and supported by horizontal poles along the walls. Strips of bark lashed the poles together. The roof was made by bending a series of poles, resulting in an arc-shaped roof.[3] The frame was covered by large pieces of bark about 4 feet (1.2 m) wide by 8 feet (2.4 m) long, sewn in place and layered as shingles, and reinforced by light poles. There were centrally located firepits and the smoke escaped through ventilation openings, later singly dubbed as a smoke hole, positioned at intervals along the roofing of the longhouse.[2]

The longhouses were divided into sections for different families, who slept on raised platforms, several of whom shared a fire in the central aisle. In an Iroquois longhouse there may have been twenty or more families which were all related through the mothers' side, along with the other relatives. Each longhouse had their clan symbol, a turtle, bear, or hawk, for example, placed over the doorway. Several longhouses constituted a village, which was usually located near water and surrounded by a palisade of tall walls made from sharpened logs for protection.

Longhouses were temporary structures that were typically used for a decade or two. A variety of factors, both environmental and social, would lead to a relocation of the settlement and construction of new longhouses.[4]

The Haudenosaunee view the longhouse as a symbol of the Iroquois Confederacy, which extended like one large longhouse across their territory. The Mohawk who lived in the eastern end of the territory are the "Keepers of the Eastern Door" and the Seneca who live in the west, the "Keepers of the Western Door." Representing the Five Nations, five (later six to include the Tuscarora) ventilation holes were created in the roof of each longhouse.

Today, with the adoption of the single family home, longhouses are no longer used as dwellings but they continue to be used as meeting halls, theaters, and places of worship.

The Longhouse Religion, known as The Code of Handsome Lake or Gaihwi:io (Good Message in Seneca and Onondaga), was founded in 1799 by the Seneca Chief Handsome Lake (Ganioda'yo) who designated the longhouse structure as their place of worship.

Northwest Coast longhouses

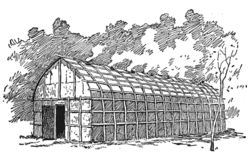

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast built their houses facing the ocean, using cedar wood. Tribes along the North American Pacific coast with a tradition of building longhouses include the Haida, Tsimshian, Tlingit, Makah, Clatsop, Coast Salish, and Multnomah people.

Longhouses were made from cedar logs or split log frame and covered with split log planks. Planks were also used for flooring. The roofs were plank-covered, sometimes with an additional bark cover. Roof types included gable and gambrel, depending on location. The gambrel roof was unique to Puget Sound Coast Salish.[5]

Each longhouse contained a number of booths along both sides of the central hallway, separated by wooden containers (akin to modern drawers). Each booth also had its own individual fire. There was one doorway, usually facing the shore. The front was often very elaborately decorated with an integrated mural of numerous drawings of faces and heraldic crest icons of raven, bear, whale, etc. A totem pole was often situated outside the longhouse, though the style varied greatly, and sometimes was even used as part of the entrance way.

The size of a home depended on the wealth of the owner, with the larger houses furnishing living quarters for up to 100 people. Within each house, a particular family had a separate cubicle. Each family had its own fire, with the families also sharing a communal central fire in the household. Usually an extended family occupied one longhouse, and cooperated in obtaining food, building canoes, and other daily tasks.

The wealthy built extraordinarily large longhouses, also known as "bighouses." The Suquamish Old Man House, built around 1850 at what became the Port Madison Reservation, and home of Chief Seattle, was 500 feet (150 m) x 40 feet (12 m)–60 feet (18 m).[5]

South America

In South America the Tucano people of Colombia and northwest Brazil traditionally combine a household in a single longhouse. The Tucano are a group of indigenous South Americans living in the northwestern Amazon, along the Vaupés River and the surrounding area. They are present in both Colombia and Brazil, although most live on the Colombian side of the border. They are usually described as being made up of many separate tribes, although the appellation is somewhat problematic due to the complex social and linguistic structure of the region.

Like most other groups of the Vaupés system, they are an exogamous patrilineal and patrilocal descent group, with a segmentary social structure. The constitutive groups live in isolated settlements in units of four to eight families dwelling in multifamily longhouses.[6] Their practice of linguistic exogamy means that members of a linguistic descent group marry outside their own linguistic descent group. As a result, it is normal for Tucano people to speak two, three, or more Tucanoan languages, and any Tucano household (longhouse) is likely to be host to numerous languages. The descent groups (sometimes referred to as tribes) all have their accompanying language.

Asia

Longhouses of various sorts have been used by numerous ethnic groups throughout Asia, from prehistoric times until today. The following are a few examples of cultures that have used longhouses and some that continue to do so.

Prehistoric

- Korea

In Daepyeong, an archaeological site of the Mumun pottery period in Korea longhouses have been found that date to circa 1100-850 B.C.E. Their layout seems to be similar to those of the Iroquois with several fireplaces arranged along the longitudinal axis of the building, indicating that the occupants were likely members of an extended household.[7]

Later the ancient Koreans started raising their buildings on stilts, so that the inner partitions and arrangements are somewhat obscure. However, the size of the buildings and their placement within the settlements suggests they were buildings for the nobles of their society or some sort of community or religious buildings. In Igeum-dong, an excavation site in South Korea, the large longhouses, 29 and 26 meters long, are situated between the megalithic cemetery and the rest of the settlement.

Traditional to Contemporary

- Borneo

Many of the inhabitants of the Southeast Asian island of Borneo (now Kalimantan, Indonesia, and States of Sarawak and Sabah, Malaysia), the Dayak, live in traditional longhouses, Rumah panjang in Malay, rumah panjai in Iban. They are built raised off the ground on stilts and are divided by a wall running along the length of the building into a more or less public area along one side and a row of private living quarters lined along the other side.

The private units, bilik, each have a single door for each family. They are usually divided from each other by walls of their own and contain the living and sleeping spaces. The kitchens, dapor, sometimes reside within this space but are quite often situated in rooms of their own, added to the back of a bilik or even in a building standing a little away from the longhouse and accessed by a small bridge due to the fear of fire, as well as reducing smoke and insects attracted to cooking from gathering in living quarters.

The corridor itself is divided into three parts. The space in front of the door, the tempuan, belongs to each bilik unit and is used privately. This is where rice can be pounded or other domestic work can be done. A public corridor, a ruai, basically used like a village road, runs the whole length in the middle of the open hall. Along the outer wall is the space where guests can sleep, the pantai. On this side a large veranda, a tanju, is built in front of the building where the rice (padi) is dried and other outdoor activities can take place. Under the roof is a sort of attic, the sadau, that runs along the middle of the house under the peak of the roof. Here the padi, other food, and other things can be stored. Sometimes the sadau has a sort of gallery from which the life in the ruai can be observed. The livestock, usually pigs and chickens, live underneath the house between the stilts.

The design of these longhouses is elegant: being raised, flooding presents little inconvenience. Being raised, cooling air circulates and having the living area above ground locates it where any breeze is more likely. Livestock shelter underneath the longhouse for greater protection from predators and the elements. The raised structure also provides security and defense against attack as well as facilitating social interaction while still allowing for privacy in domestic life. These advantages may account for the persistence of this type of design in contemporary Borneo societies.[8]

The houses built by the different tribes and ethnic groups differ somewhat from each other. Houses described as above may be used by the Iban Sea Dayak and Melanau Sea Dayak. Similar houses are built by the Bidayuh, Land Dayak, however with wider verandas and extra buildings for the unmarried adults and visitors. The buildings of the Kayan, Kenyah, Murut, and Kelabit used to have fewer walls between individual bilik units. The Punan seem to be the last ethnic group that adopted this type of house building. The Rungus of Sabah in north Borneo build a type of longhouse with rather short stilts, the house raised three to five feet of the ground, and walls sloped outwards.

In modern times many of the older longhouses have been replaced with buildings using more modern materials but of similar design. In areas where flooding is not a problem, beneath the longhouse between the stilts, which was traditionally used for a work place for tasks such as threshing, has been converted into living accommodation or has been closed in to provide more security.

- Siberut

Uma are traditional houses of the Sakuddei found on the western part of the island of Siberut in Indonesia. The island is part of the Mentawai islands off the west coast of Sumatra.

Uma longhouses are rectangular with a verandah at each end. They can be as much as 300 square meters (3,200 sq ft) in area. Villages are located along the river banks and made up of one or more communal Uma longhouses, as well as single-storey family houses known as lalep. Villages house up to 300 people and the larger villages were divided into sections along patrilineal clans of families each with their own uma.

Built on piles or stilts, the uma traditionally have no windows. The insides are separated into different dwelling spaces by partitions which usually have inter-connecting doors. The front has an open platform serving as main entrance place followed by a covered gallery. The inside is divided into two rooms, one behind the other. On the back there is another platform. The whole building is raised on short stilts about half a meter off the ground. The front platform is used for general activities while the covered gallery is a favorite place for the men to host guests, and the men usually sleep there. The first inside room is entered by a door and contains a central communal hearth and a place for dancing. There are also places for religious and ritual objects and activities. In the adjoining room the women and their small children as well as unmarried daughters sleep, usually in compartments divided into families. The platform on the back is used by the women for their everyday activities. Visiting women usually enter the house from the back.

- Vietnam

The Mnong people of Vietnam also have a tradition of building long houses (Nhà dài) from bamboo with a grass roof. In contrast to the jungle versions of Borneo these have shorter stilts and use a veranda in front of a short (gable) side as main entrance.

- Nepal

The Tharu people are indigenous people living in the Terai plains on the border of Nepal and India in the region known as the Tarai.[9] These people continue to live in longhouses which may hold up to 150 people. Their longhouses are built of mud with lattice walls. The Tharu women cover the outer walls and verandahs with colorful paintings. Some of the paintings may be purely decorative, while others are dedicated to Hindu gods and goddesses.[10]

Europe

Longhouses have existed in Europe since prehistoric times. Some were large, capable of housing multiple families; others were smaller and were used by a single family together with their livestock, or for storage of cereal grains.

Prehistoric

There are two European longhouse types that are now extinct.

- The Neolithic long house

The Neolithic longhouse was a long, narrow timber dwelling built by the first farmers in Europe beginning at least as early as the period 5000 to 6000 B.C.E.[11] This type of architecture represents the largest free-standing structure in the world in its era.

It is thought that these Neolithic houses had no windows and only one doorway. The end farthest from the door appears to have been used for grain storage, with working activities being carried out in the better lit door end and the middle used for sleeping and eating. Structurally, the Neolithic long house was supported by rows of large timbers holding up a pitched roof. The walls would not have supported much weight and would have been quite short beneath the large roof. Sill beams ran in foundation trenches along the sides to support the low walls. The long houses would measure around 20 meters (66 ft) in length and 7 meters (23 ft) in width and could have housed twenty or thirty people.

The Balbridie timber house in what is present day Aberdeenshire, Scotland offers an outstanding example of these early structures. This was a rectangular structure with rounded ends, measuring 24 meters (79 ft) x 12 meters (39 ft), it was originally thought to be post-Roman, but radiocarbon dating of charred cereal grains established dates from 3900-3500 B.C.E., falling into the early Neolithic.[12] Archaeological excavations have revealed extant timber postholes that delineate the support pieces of the original structure. This site is strategically located in a fertile agricultural area along the River Dee very close to an ancient strategic ford of the river and also near an ancient timber trackway known as the Elsick Mounth.[13]

- The Germanic cattle farmer longhouse

These longhouses emerged along the southwestern North Sea coast in the third or fourth century B.C.E. and might be the ancestors of several medieval house types such as the Scandinavian langhus and the German and Dutch Fachhallenhaus, although there is no evidence of a direct connexion.

This European longhouse first appeared during the period of the Linear Pottery culture about 7,000 years ago and has been discovered during the course of archaeological excavations in widely differing regions across Europe, including the Ville ridge west of Cologne. The longhouse differed from later types of house in that it had a central row of posts under the roof ridge. It was therefore not three- but four-aisled. To start with, cattle were kept outside overnight in Hürden or pens. With the transition of agriculture to permanent fields the cattle were brought into the house, which then became a so-called Wohnstallhaus or byre-dwelling.

Medieval

There are several medieval European longhouse types, some have survived, including the following:

- British Isles

- The Dartmoor longhouse

This is a type of traditional home, found on the high ground of Dartmoor, in the south west of the United Kingdom. The earliest were small, oblong, one storied buildings that housed both the farmer and his livestock and are thought to have been built in the thirteenth century, and they continued to be constructed throughout the medieval period, using local granite.[14] Many longhouses are still inhabited today (although obviously adapted over the centuries), while others have been converted into farm buildings.

The Dartmoor longhouse consists of a long, single-storey granite structure, with a central 'cross-passage' dividing it into two rooms, one to the left of the cross-passage and the other to the right. The one at the higher end of the building was occupied by the human inhabitants; their animals were kept in the other, especially during the cold winter months. The animal quarters were called the 'shippon' or 'shippen'; a word still used by many locals to describe a farm building used for livestock.

Early longhouses would have had no chimney—the smoke from a central fire simply filtered through the thatched roof. Windows were very small or non-existent, so the interior would have been dark. The cross-passage had a door at either end, and with both of these open a breeze was often created which made it an ideal location for winnowing.

This simple floor plan is clearly visible at the abandoned medieval village at Hound Tor, which was inhabited from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. Excavations during the 1960s revealed four longhouses, many featuring a central drainage channel, and several smaller houses and barns.

In later centuries, the longhouses were adapted and expanded, often with the addition of an upper floor and a granite porch to protect against the elements. Substantial fireplaces and chimneys were also added, and can be seen at many of the surviving Dartmoor longhouses today.

Higher Uppacott, one of the few remaining longhouses to retain its original unaltered shippon, is a Grade I listed building, and is now owned by the Dartmoor National Park Authority.[15]

- Clay Dabbins of the Solway Plain

Clay houses have been built on the Solway Plain in the northwest of Cumbria, England since medieval times. These buildings originated as single-storey longhouses, built in the style of the Middle Ages and housing family and stock in a single, undivided building open to the roof, with an open fire in the floor of the domestic end and no chimney. Mud was used for the walls rather than timber or stone due to the shortage of those materials; most of the Solway Plain has been overlain by a thick layer of boulder clay since the last Ice Age.[16]

- The Scottish "Blackhouse"

The "Blackhouse" or taighean dubha is a traditional type of house which used to be common in Highlands of Scotland and the Hebrides.[17]

The buildings were generally built with double wall dry-stone walls packed with earth and wooden rafters covered with a thatch of turf with cereal straw or reed. The floor was generally flagstones or packed earth and there was a central hearth for the fire. There was no chimney for the smoke to escape though. Instead the smoke made its way through the roof. The blackhouse was used to accommodate livestock as well as people. People lived at one end and the animals lived at the other with a partition between them.

The Isle of Lewis examples have clearly been modified to survive in the tough environment of the Outer Hebrides. Low rounded roofs, elaborately roped were developed to resist the strong Atlantic winds and thick walls to provide insulation and to support the sideways forces of the short driftwood roof timbers.[18]

- France

- The French longère

This was the house of peasants (and their animals) throughout Western France, as evidenced particularly in Brittany, Normandy, Mayenne, and Anjou. A narrow house, it extends lengthwise with its openings placed more often in a long wall than in a gable wall. The livestock were confined to the end opposite the hearth.[19]

- Germany

- The Low German house (Fachhallenhaus)

The Low German house appeared during the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries. Until its decline in the nineteenth century, this rural, agricultural farmhouse style was widely distributed through the North German Plain, all the way from the Lower Rhine to Mecklenburg. Even today, the Fachhallenhaus still characterizes the appearance of many north German villages.

The Low German house or Fachhallenhaus is a type of German timber-framed farmhouse, which combines living quarters, byre and barn under one roof.[20]. It is built as a large hall with bays on the sides for livestock and storage and with the living accommodation at one end. Similar in construction to the neolithic longhouse, its roof structure rested as before on posts set into the ground and was therefore not very durable or weight-bearing. As a result these houses already had rafters, but no loft to store the harvest. The outer walls were only made of wattle and daub (Flechtwerk).

By the Carolingian era, houses built for the nobility had their wooden, load-bearing posts set on foundations of wood or stone. Such uprights, called Ständer, were very strong and lasted several hundred years. These posts were first used for farmhouses in northern Germany from the thirteenth century, and enable them to be furnished with a load-bearing loft. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the design of the timber-framing was further perfected.

From the outset, and for a long time thereafter, people and animals were accommodated in different areas within a large room. Gradually the living quarters were separated from the working area and animals. The first improvements were separate sleeping quarters for the farmer and his family at the rear of the farmhouse. Sleeping accommodation for farmhands and maids was created above (in Westphalia) or next to (in Lower Saxony and Holstein) the livestock stalls at the sides. As the demand for comfort and status increased, one or more rooms would be heated. Finally the stove was moved into an enclosed kitchen rather than being in a Flett or open hearth at the end of the hall.

By the end of the nineteenth century this type of farmhouse was outmoded. What was once its greatest advantage—having everything under a single roof—now led to its decline. Rising standards of living meant that the smells, breath, and manure from the animals was increasingly viewed as unhygienic. In addition the living quarters became too small for the needs of the occupants. Higher harvest returns and the use of farm machinery in the Gründerzeit led to the construction of modern buildings. The old stalls under the eaves were considered too small for cattle. Since the middle of the nineteenth century fewer and fewer of these farmhouses were built and some of the existing ones were converted to adapt to new circumstances.

The Low German house is still found in great numbers in the countryside. Most of the existing buildings have however changed over the course of the centuries as modifications have been carried out. Those farmhouses that have survived in their original form are mainly to be found in open air museums like the Westphalian Open Air Museum at Detmold (Westfälisches Freilichtmuseum Detmold) and the Cloppenburg Museum Village (Museumsdorf Cloppenburg). At the end of the twentieth century old timber-framed houses, including the Low German house, were seen as increasingly valuable. As part of a renewed interest in the past, many buildings were restored and returned to residential use. In various towns and villages, such as Wolfsburg-Kästorf, Isernhagen, and Dinklage, new timber-framed homes were built during the 1990s, whose architecture is reminiscent of the historic Hallenhäuser.

- Scandinavia

- The Scandinavian or Viking Langhus

Throughout the Norse lands (medieval Scandinavia including Iceland) people lived in longhouses (langhús). These were built with a stone base and wooden frame, and turf covering the roof and walls. In regions that had a limited supply of wood, such as Iceland, the walls were made from turf.[21]

These longhouses were typically 5 to 7 meters wide (16 to 23 feet) and anywhere from 15 to 75 meters long (50 to 250 feet), depending on the wealth and social position of the owner. A Viking chief would have a longhouse in the center of his farm.

Notes

- ↑ Lee Sultzman, Iroquois History. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Carl Waldman, Atlas of the North American Indian (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0816068593), 59.

- ↑ New York State Museum, Longhouses. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ↑ John Ferguson, Longhouses and Archaeology, presentation by Dean Snow, April 27, 1995. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Wayne P. Suttles and William C. Sturtevant (eds.), Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast (Smithsonian Institution, 1990, ISBN 978-0160203909), 491.

- ↑ Jean Elizabeth Jackson, "Language Identity of the Vaupés Indians," 53.

- ↑ Martin T. Bale and Min-jung Ko, "Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Pottery Period Korea," Asian Perspectives 45(2) (2006):159-187.

- ↑ James J. Fox (ed.), Inside Austronesian Houses (Canberra: The Australian National University, 1993, ISBN 978-0731515950).

- ↑ The Tharu Page www.macalester.edu. Retrieved June 15, 2011

- ↑ Kurt W. Meyer and Pamela Deuel, The Tharu of the Tarai www.asianart.com (March 1997). Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ Rodney Castleden, The Stonehenge People: An Exploration of Life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 B.C.E. (Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-04150406551987).

- ↑ Peter Rowley-Conwy, Great Sites: Balbridie British Archaeology 64 (April 2002). Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Elsick Mounth: Ancient Trackway in Scotland in Aberdeenshire The Megalithic Portal, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ The Longhouses of Dartmoor Legendary Dartmoor. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Interactive Visit to Higher Uppacott Virtually Dartmoor.

- ↑ Nina Jennings, The Building of the Clay Dabbins of the Solway Plain: Materials and Man-Hours Vernacular Architecture 33 (2002): 19-27. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ The Blackhouse of the Highlands Dualchas Building Design, 2001. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Alexander Fenton, The Arnol Blackhouse, Isle of Lewis (Historic Scotland, 2005, ISBN 978-1903570852).

- ↑ Christian Lassure, The Vernacular Architecture of France 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ T.H. Elkins, Germany (London: Chatto & Windus, 1972), 266.

- ↑ William R. Short, Longhouses Hurstwic. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bale, Martin T., and Min-jung Ko. "Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Pottery Period Korea." Asian Perspectives 45(2) (2006):159-187.

- Castleden, Rodney. The Stonehenge People: An Exploration of Life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 B.C.E.. Routledge, 1992. ISBN 978-0415040655

- Dawson, Barry, and John Gillow. The Traditional Architecture of Indonesia. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994. ISBN 978-0500341322

- Dickson, M.G. Sarawak and its People. Borneo Literature Bureau, 1964.

- Elkins, T.H. Germany. London: Chatto & Windus, 1972. ASIN B0011Z9KJA

- Fenton, Alexander. The Arnol Blackhouse, Isle of Lewis. Historic Scotland, 2005. ISBN 978-1903570852

- Fox, James J. (ed.). Inside Austronesian Houses. Canberra: The Australian National University, 1993. ISBN 978-0731515950

- Jackson, Jean Elizabeth. The Fish People: Linguistic Exogamy and Tukanoan Identity in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0521278225

- Jackson, Jean Elizabeth. "Language Identity of the Vaupés Indians" in Richard Bauman and Joel Sherzer (eds.) Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking. Cambridge University Press, 1989, 50–64. ISBN 978-0521379335

- Metcalf, Peter. The Life of the Longhouse: An Archaeology of Ethnicity. Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0521110983

- Morrison, Hedda. Life in a Longhouse. Singapore: Summer Times, 1988. ISBN 978-9971976026

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Rainforest Shamans. Green Books Ltd., 1997. ISBN 978-0952730248

- Suttles, Wayne P., and William C. Sturtevant (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. Smithsonian Institution, 1990. ISBN 978-0160203909

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Waldman, Carl. Atlas of the North American Indian. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0816068593

- Whittle, A.W.R. Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0521449205

External links

All links retrieved March 12, 2025.

- A Mohawk Iroquois Village, New York State Museum

- Blackhouse Museum

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Long_house history

- Native_American_long_house history

- Uma_longhous history

- Neolithic_long_house history

- Low_German_house history

- Dartmoor_longhouse history

- Blackhouse_(building) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.