Norman Ireland

The later medieval period in Ireland ("Norman Ireland") was dominated by the Cambro-Norman invasion of the country in 1171. Previously, Ireland had seen intermittent warfare between provincial kingdoms over the position of High King. This situation was transformed by the intervention in these conflicts of Norman mercenaries and later the King of England. After their successful conquest of England, the Normans turned their attention to Ireland. Ireland was made a Lordship of the King of England and much of its land was seized by Norman barons. However, with time Hiberno-Norman rule shrank to a territory known as pale ("the Pale") stretching from Dublin to Dundalk. The Hiberno-Norman lords elsewhere in the country became Gallicized and integrated in Gaelic Irish society. Henry II claimed the Pope's blessing in subjugating Ireland, whose Church was regarded as deviant; his task was to bring it firmly under papal authority. The Norman period technically continued until Henry VIII of England set out to re-assert English rule over Ireland in 1534, ushering in a new period. Henry changed the title from "Lord of Ireland" to king.

He, too, looked on the Irish Church as deviant. Having embraced Protestantism, Henry VIII tried to force this onto the Irish. Irish Catholics soon faced many restrictions; Protestants, settling in Ireland, took control of almost all the land. By the next century, Ireland was firmly under British rule. Both the Norman and the later period of English rule can best be described as misrule, even as tyranny. The settlers and their heirs prospered while the Irish often starved. Only after repeated revolts did Britain agree to Ireland's independence. Even then, Northern Ireland was Partitioned from the South because of pressure from the North's Protestant majority that refused to join the Catholic-majority South. Centuries of oppression at Norman-English hands left many scars and wounds. When, after World War II, territorial rivalry in the European space finally gave way to the idea of creating a common home, new relations based on respect for human rights and justice developed between these former foes. Only when people find ways to heal old wounds can the human race hope to exchange division for unity. Only then can a world of peace and plenty for all replace one in which a few flourish while many perish.

Arrival of the Normans (1167â1185)

By the twelfth century, Ireland was divided politically into a shifting hierarchy of petty kingdoms and over-kingdoms. Power was concentrated into the hands of a few regional dynasties contending against each other for control of the whole island. The Northern UĂ NĂ©ill ruled much of what is now Uladh (Ulster). Their kinsmen, the Southern UĂ NĂ©ill, were Kings of Breaga (Meath). The kingship of Laighean (Leinster) was held by the dynamic UĂ Chinnsealaigh dynasty. A new kingdom rose between Leinster and Mumhan (Munster), Osraighe, ruled by the family of Mac Giolla PhĂĄdraig. Munster was nominally controlled by the Mac CĂĄrthaigh, who were however in reality often subject to the UĂ Bhriain of Tuadh Mumhan (Thomond). North of Thomond, Connachta Connacht's supreme rulers were the UĂ Chonchobhair.

After losing the protection of TĂr Eoghain (Tyrone) Chief, Muircheartach Mac Lochlainn, High King of Ireland, who died in 1166, Dermot MacMurrough (Irish Diarmaid Mac Murchada), was forcibly exiled by a confederation of Irish forces under the new High King, RuaidhrĂ Ă Conchobhair.

Diarmaid fled first to Bristol and then to Normandy. He sought and obtained permission from Henry II of England to use the latter's subjects to regain his kingdom. By 1167, MacMurrough had obtained the services of Maurice Fitz Gerald and later persuaded RhĆ·s ap Gruffydd Prince of Deheubarth to release Maurice's half-brother Robert Fitz-Stephen from captivity to take part in the expedition. Most importantly he obtained the support of Cambro- Norman Marcher Lord Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke known as Strongbow.

The first Norman knight to land in Ireland was Richard fitz Godbert de Roche in 1167, but it was not until 1169 that the main forces of Normans, along with their mercenaries which consisted of Welsh and Flemings landed in Loch Garman Wexford. Within a short time Leinster was regained, Port LĂĄirge Waterford and Baile Ătha Cliath Dublin were under Diarmaid's control, and he had Strongbow as a son-in-law, after offering his eldest daughter Aoife to him in marriage in 1170, and named him as heir to his kingdom. This latter development caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to visit Leinster to establish his authority.

The Papal Bull and Henry's invasion

Pope Adrian IV (the first English pope, in one of his earliest acts) had already issued a Papal Bull in 1155, giving Henry authority to invade Ireland as a means to bring the Irish Church into conformity with Roman Catholic practice and belief. Ireland followed the Celtic Christian tradition. Abbots rather than bishops exercised authority; monasteries consisted on mixed communities of married and celibate. Women, too, could serve as priests. Easter was celebrated on a different date and monk's wore their tonsure from ear to ear, not on the crown.[1] Ireland was considered to be more pagan than Christian. It was Henry's job to complete the Christianizing process and to bring the Irish Church into the papal fold by paying its taxes to Rome. Little contemporary use, however, was made of the Bull Laudabiliter since its text enforced papal suzerainty not only over the island of Ireland but of all islands off of the European coast, including England, in virtue of the Constantinian donation. The so-called Donation of Constantine is the document cited by successive popes to support their claim to political or temporal power, which they claimed was gifted them by Constantine I.[2] When popes vested kings such as Henry the right to rule "pagan" territory, this was justified with reference to the Donation, which also lies behind the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) that more or less divided the world between Portugal and Spain. The Bull was renewed by Pope Alexander III in 1171, and approved by a Synod of Irish bishops.

The relevant section of Laudabiliter read:

There is indeed no doubt, as thy Highness doth also acknowledge, that Ireland and all other islands which Christ the Sun of Righteousness has illumined, and which have received the doctrines of the Christian faith, belong to the jurisdiction of St. Peter and of the holy Roman Church.[3]

Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Both Waterford and Dublin were proclaimed Royal Cities. Adrian's successor, Pope Alexander III ratified the grant of Irish lands to Henry in 1172. Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son John with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"). When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King John, the "Lordship of Ireland" fell directly under the English Crown.

Henry was happily acknowledged by most of the Irish Kings, who saw in him a chance to curb the expansion of both Leinster and the Hiberno-Normans. This led to the ratification of the Treaty of Windsor (1175) between Henry and RuaidhrĂ. However, with both Diarmaid and Strongbow dead (in 1171 and 1176), Henry back in England and RuaidhrĂ unable to curb his nominal vassals, within two years it was not worth the vellum it was inscribed upon. John de Courcy invaded and gained much of east Ulster in 1177, Raymond le Gros had already captured Limerick and much of north Munster, while the other Norman families such as Prendergast, fitz Stephen, fitz Gerald, fitz Henry, de Ridelsford, de Cogan, and le Poer were actively carving out virtual kingdoms for themselves.

Impact of the Norman invasion

What eventually occurred in Ireland in the late 12th and early 13th century was a change from acquiring lordship over men to colonizing land. The Cambro- Norman invasion resulted in the founding of walled borough towns, numerous castles and churches, the importing of tenants and the increase in agriculture and commerce, these were among the many permanent changes wrought by the Norman invasion and occupation of Ireland. Normans altered Gaelic society with efficient land use, introducing feudalism to the existing native tribal-dynastic crop-sharing system. Feudalism never took on in large parts of Ireland, but it was an attempt to introduce cash payments into farming, which was entirely based on barter. Some Normans living further from Dublin and the east coast adopted the Irish language and customs, and intermarried, and the Irish themselves also became irrevocably "Normanized." Many Irish people today bear Norman-derived surnames, although these are far more prevalent in the provinces of Leinster and Munster, where there was a larger Norman presence.

The system of counties was introduced from 1297, though the last of the counties of Ireland was not shired until 1610. As in England, the Normans blended the continental European county with the English shire, where the king's chief law enforcer was the shire-reeve (sheriff). Many Irish towns are prefixed Bally-, which derived from the French "ville," and towns were perhaps the Normans' greatest contribution. Starting with Dublin in 1192, royal charters were issued to foster trade and to give extra rights to townspeople.

The church attempted to center congregations on the parish and not as formerly on abbeys, and built hundreds of new churches in 1172-1348. The first attempt to record Ireland's wealth at the parish level was made in the records of Papal Taxation of 1303, required to operate the new tithing system. Regular canon law tended to be limited to the areas under central Norman control.

The traditional Irish legal system, the "Brehon Law" continued in areas outside central control, but the Normans introduced Henry II's reforms including new concepts such as prisons for criminals. The Brehon system was typical of other north European customary systems and required fines to be paid by a criminal, the amount depending on the victim's status.

While the Norman political impact was considerable, it was untidy and not uniform, and the stresses on the Lordship in 1315-48 meant that de facto control of most of Ireland slipped from its grasp for over two centuries.

Lordship of Ireland (1185â1254)

Initially the Normans controlled large swathes of Ireland, securing the entire east coast, from Waterford up to eastern Ulster and penetrating as far west as Gaillimh (Galway) and Maigh Eo (Mayo). The most powerful forces in the land were the great Hiberno-Norman Earldoms such as the Geraldines, the Butlers and the de Burghs (Burkes), who controlled vast territories which were almost independent of the governments in Dublin or London. The Lord of Ireland was King John of England, who, on his visits in 1185 and 1210, had helped secure the Norman areas from both the military and the administrative points of view, while at the same time ensuring that the many Irish kings were brought into his fealty; many, such as Cathal Crobhdearg Ua Conchobhair, owed their thrones to him and his armies. The "Pale" was the divide between the "civilized" and the yet-to-be-civilized; "Those within the Pale were civilized, Christian, loyal to the Pope; those outside the Pale were barbaric, heretic or pagan."[4]

The Normans also were fortunate to have leaders of the caliber of the Butler, Marshall, de Lyvet (Levett), de Burgh, de Lacy and de Broase families, as well as having the dynamic heads of the first families.[5][6][7] Another factor was that after the loss of Normandy in 1204, John had a lot more time to devote to Irish affairs, and did so effectively even from afar.

Gaelic resurgence, Norman decline (1254â1536)

However, the Hiberno-Normans suffered from a series of events that slowed, and eventually ceased, the spread of their settlement and power. Firstly, numerous rebellious attacks were launched by Gaelic lords upon the English lordships. Having lost pitched battles to Norman knights, to defend their territory, the Gaelic chieftains now had to change tactics, and deal with the charging armored knights. They started to rely on raids against resources, and surprise attacks. This stretched resources of the Normans, reduced their number of trained knights, and often resulted in the chieftains regaining territory. Secondly, a lack of direction from both Henry III and his successor, Edward I (who were more concerned with events in England, Wales, Scotland, and their continental domains) meant that the Norman colonists in Ireland were to a large extent deprived of (financial) support from the English monarchy. This limited the ability to hold territory. Furthermore, the Norman's position deteriorated due to divisions within their own ranks. These caused outright war between leading Hiberno-Norman lords such as the de Burghs, FitzGeralds, Butlers, and de Berminghams. Finally, the division of estates among heirs split Norman lordships into smaller, less formidable unitsâthe most damaging being that of the Marshalls of Leinster, which split a large single lordship into five.

Politics and events in Gaelic Ireland served to draw the settlers deeper into the orbit of the Irish, which on occasion had the effect of allying them with one or more native rulers against other Normans.

Hiberno-Norman Ireland was deeply shaken by three events of the fourteenth century.

- The first was the invasion of Ireland by Edward Bruce of Scotland who, in 1315, rallied many of the Irish lords against the English presence in Ireland. Edward II of England appointed his favorite, Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall as his Lt. Governor in 1308, followed by [[Roger Mortimer, Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March in 1315. Both men extended Norman rule and Roger moved against Bruce and his allies. Although Bruce was eventually defeated in Ireland at the Battle of Faughart, near Dundalk, his troops caused a great deal of destruction, especially in the densely settled area around Dublin. In this chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land that their families had lost since the conquest and held them after the war was over. A few English partisans like Gilbert de la Roche turned against the English king and sided with Bruce, largely because of personal quarrels with the English monarchy.[8][9]

- The second was the murder of William Donn de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster, in June 1333. This resulted in his lands being split in three among his relations, with the ones in Connacht swiftly rebelling against the Crown and openly siding with the Irish. This meant that virtually all of Ireland west of the Shannon was lost to the Hiberno-Normans. It would be well over two hundred years before the Burkes, as they were now called, were again allied with the Dublin administration.

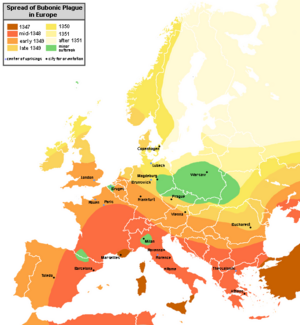

- The third calamity for the medieval English presence in Ireland was the Black Death, which arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. A celebrated account from a monastery in Cill Chainnigh (Kilkenny) chronicles the plague as the beginning of the extinction of humanity and the end of the world. The plague was a catastrophe for the English habitations around the country and, after it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale, a fortified area around Dublin.

Additional causes of the Gaelic revival were political and personal grievances against the Hiberno-Normans, but especially impatience with procrastination and the very real horrors that successive famines had brought. Pushed away from the fertile areas, the Irish were forced to eke out a subsistence living on marginal lands, which left them with no safety net during bad harvest years (such as 1271 and 1277) or in a year of famine (virtually the entire period of 1311â1319).

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs, becoming known as the Old English, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, became "more Irish than the Irish themselves."[10] Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the Reformation. The authorities in the Pale grew so worried about the "Gaelicisation" of Ireland that, in 1367 at a Parliament in Kilkenny, they passed special legislation (known as the Statutes of Kilkenny) banning those of English descent from speaking the Irish language, wearing Irish clothes or inter-marrying with the Irish. Since the government in Dublin had little real authority, however, the Statutes did not have much effect.

Throughout the fifteenth century, these trends proceeded apace and central government authority steadily diminished. The monarchy of England was itself thrown into turmoil during the Wars of the Roses, and as a result English involvement in Ireland was greatly reduced. Successive kings of England delegated their constitutional authority over the lordship to the powerful Fitzgerald earls of Kildare, who held the balance of power by means of military force and widespread alliances with lords and clans. This in effect made the English Crown even more remote to the realities of Irish politics. At the same time, local Gaelic and Gallicized lords expanded their powers at the expense of the central government in Dublin, creating a polity quite alien to English ways and which was not overthrown until the successful conclusion of the Tudor reconquest.

Legacy

When the Tudor re-conquest took place, England under Henry VIII had embraced Protestantism. Henry took a leaf out of the Norman invasion and conquest by settling English and Scottish Protestants in Ireland as colonial masters. The Irish were still regarded as primitive, unruly, in need of guidance and discipline from a superior people. Legal restrictions were soon imposed. From 1607, few civil or public service posts were open to them. They could not sit in Parliament (until 1829). Strict land ownership laws made it almost impossible for Catholic to purchase property, which meant that the land they did own was usually sub-divided among their heirs. This resulted in smaller and smaller holdings producing insufficient food.[11] The dispossession that had started under the Normans continued at an even greater pace so that by the start of the nineteenth century, Protestants, though a small minority, owned 90 percent of all property.[4] Protestant settlers and their descendants looked on the Irish in much the same way as had the Normans, positing an "us" and "them" polarity. Mainly Calvinist, the Protestants saw themselves as "honest, pious, thrifty and hard working"" and saw the Catholics as "lazy, stupid and violent."[12] If the Pope had given Ireland to the Normans, the settlers and their heirs saw it as their God-given promised land. In this view, the Irish no longer had a legitimate claim to the land, anymore than the Canaanites had to theirs once the Children of Israel had claimed their Promised Land.[13]

Later, this led to famine and mass starvation. Many Scottish Protestants settled in the North of Ireland, which eventually led to the Partition of Ireland in 1922. When, after many anti-British rebellionsâBritain finally granted home rule to Ireland, Northern Protestants refused to be part of a Catholic majority state. Forming a minority in the North, the "partition" solution was applied, similar to the solution later applied to Hindu-Muslim tension in India (in 1947). Yet, a love-hate relationship existed between the English and the Irish due to the long relationship, including the lengthy period of Norman rule. The Irish produced such exquisite poetry and literature in English that they eventually turned their oppressors' language into a tool to challenge English mastery of their own tongue, let alone their assumption of cultural superiority.

Notes

- â Bennett (2008), 50.

- â Fordham University, The Donation of Constantine, Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- â Library Ireland, Pope Adrian's Bull Laudabiliter and Note Upon It. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- â 4.0 4.1 Bennett (2008), 52.

- â H.S. Sweetman, "Philip de Livet," Calendar of Documents, Relating to Ireland (London, UK: Longman).

- â John Debrett,"John Lyvet, Lord, Ireland, 1302," Debrett's Peerage of England, Scotland and Ireland (London, 1839).

- â H.S. Sweetman, "Richard de Burgh, John Livet, Maurice FitzGerald," Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland (London, UK: Longman, 1875).

- â "Gilbert de la Roche beheaded," Calendar of Patent Rolls (Preserved in the Public Record Office, Great Britain Public Record Office, 1903).

- â "Seizure of Gilbert de la Roche estates, forfeited and conveyed over to John Lyvet, Ireland," Calendar of Patent Rolls (Preserved in the Public Record Office, Great Britain Public Record Office, 1903).

- â Cahill (1995), 213.

- â Bennett (2008), 54.

- â Bennett (2008), 53-4.

- â Bennett. 2008. page 53.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Clinton. 2008. In Search of Solutions: The Problem of Religion and Conflict. London, UK: Equinox Pub. ISBN 9781845532390.

- Cahill, Thomas. 1995. How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. New York, NY: Nan A. Talese, Doubleday. ISBN 9780385418485.

- Duffy, SeĂĄn. 1997. Ireland in the Middle Ages. British History in Perspective. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312163891.

- McCaffrey, Carmel, and Leo Eaton. 2002. In Search of Ancient Ireland: The Origins of the Irish, From Neolithic Times to the Coming of the English. Chicago, IL: New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 9781561310722.

- Orpen, Goddard Henry. 2005. Ireland Under the Normans, 1169-1333. Dublin, IE: Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851827152.

- Otway-Ruthven, Annette Jocelyn. 1968. A History of Medieval Ireland. London, UK: Benn. ISBN 9780510278014.

- Roche, Richard. 1995. The Norman Invasion of Ireland. Dublin, IE: Anvil Books. ISBN 9780947962814.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.