Partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland took place on May 3, 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The entire island of Ireland provisionally became the Irish Free State on December 6, 1922. However, the Parliament of Northern Ireland exercised its right to opt out of the new Dominion the following day. Partition created two territories on the island of Ireland: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Today the former is still known as Northern Ireland and while the latter is known simply as Ireland (or, if differentiation between the state and the whole island is required, the state can be referred to as the Republic of Ireland).

The Protestant majority in the North wanted to remain within the United Kingdom. Partition almost always creates as well as solves problems, leaving minorities on both sides of the border. If the world is to become a place of peace and plenty for all people, strategies that bring us together need to take priority over those that divide us. Partition builds barriers, not bridges. Partition may sometimes be necessary as a pragmatic strategy to avoid bloodshed but a partitioned world will not be able to make our planet a common home, so that it becomes a shared not a contested space.

Partition

Background

Since Henry VIII of England's conversion to Protestantism and restoration of English power over Ireland, a process of settling Protestants began and of privileging Protestants economically and politically began. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, 90 percent of all land in Ireland belonged to Protestants.[1] Most settlers were Scottish Calvinism who crossed the short passage from West Scotland to the country of Ulster in the North of Ireland. While Protestants were a small minority in the South they became a majority in the North. Regarding Catholics as modern-day Canaanites, many Ulster Scots believed that Ireland was their promised land and that they should separate themselves from the Catholics as the children of Israel did from the Canaanites. The Catholics, like the Canaanites, were a like "snares and traps."[2] During the nineteenth century, when successive British governments wanted to grant Ireland "Home Rule" bill after bill presented to Parliament failed because the very interests that Britain had created in Ireland conspired to vote against them. There were powerful Irish Peers in the House of Lords. Most Irish Protestants opposed Home Rule, favoring continued union with the United Kingdom. Politically, supporters of union became known as Loyalists and as Unionists. In 1912, faced by what many Northern Irish Unionists feared was a bill that would become law, a majority of the population signed the Covenant (men) and the Declaration (women). The men pledged to defend their "equal citizenship" within the United Kingdom and that they would not recognize any Parliament forced upon them while the women pledged to support the men. What Protestants feared that a free Ireland would be dominated by Catholics at their cost. However, after World War I and the Easter Rising Britain needed to rid itself of what many called the "Irish problem" (constant rebellion and the cost of governing a country that did not want to be ruled). Finally, a Government of Ireland Act was poised to become law. The original intend had been to grant self-government to the whole island but protest from the North and the threat of violence resulted in what was effectively a partition plan. The South did not formally agree to partition, indeed Britain did not consult the whole people of Ireland on this issue and refused to take Ireland's case to the Paris Peace Conference even though the rights of small states and the right to self-determination was within its remit.[3]

The 1920 Government of Ireland Act

On May 3, 1921 the Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned the island into two autonomous regions Northern Ireland (six northeastern counties) and Southern Ireland (the rest of the island). Afterwards, institutions and a government for Northern Ireland were quickly established. Meanwhile the institutions of Southern Ireland generally failed to function or take root as the large majority of Irish Members of Parliament gave their allegiance to Dáil Éireann as part of the Irish War of Independence. That war ultimately led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty which envisaged the establishment of an independent Dominion, the Irish Free State, provisionally for the entire island of Ireland.[4]

The Treaty was given legal effect in the United Kingdom through the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922. That Act established, on 6 December 1922, the new Dominion for the whole island of Ireland. As such, on 6 December 1922, Northern Ireland stopped being part of the United Kingdom and became an autonomous region of the newly created Irish Free State. However, the Treaty and the laws which implemented it also allowed Northern Ireland to opt out of the Irish Free State. Under Article 12 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland could exercise its opt out by presenting an address to the King requesting not to be part of the Irish Free State. Once the Treaty was ratified, the Parliament of Northern Ireland had one month (dubbed the Ulster month) to exercise this opt out during which month the Irish Free State Government could not legislate for Northern Ireland, holding the Free State’s effective jurisdiction in abeyance for a month.

Realistically, it was always certain that Northern Ireland would opt out and rejoin the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, speaking in the Parliament October 27, 1922 said that “when the 6th of December is passed the month begins in which we will have to make the choice either to vote out or remain within the Free State.” He said it was important that that choice was made as soon as possible after December 6, 1922 “in order that it may not go forth to the world that we had the slightest hesitation.”[5] On December 7, 1922 (the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State) the Parliament demonstrated its lack of hesitation by resolving to make the following address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State:

”MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN, We, your Majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Senators and Commons of Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled, having learnt of the passing of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922, being the Act of Parliament for the ratification of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, do, by this humble Address, pray your Majesty that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland.”[6]

On 13 December 1922 Prime Minister Craig addressed the Parliament reporting that the King had responded to the Parliament’s address as follows:

“I have received the Address presented to me by both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in pursuance of Article 12 of the Articles of Agreement set forth in the Schedule to the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act, 1922, and of Section 5 of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922, and I have caused my Ministers and the Irish Free State Government to be so informed.”[6]

With this, Northern Ireland had left the Irish Free State and rejoined the United Kingdom. If the Parliament of Northern Ireland had not made such a declaration, under Article 14 of the Treaty Northern Ireland, its Parliament and government would have continued in being but the Oireachtas would have had jurisdiction to legislate for Northern Ireland in matters not delegated to Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act. This, of course, never came to pass.

The "Irish Problem" from 1886

In the United Kingdom general election, 1885 the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party won the balance of power in the House of Commons, in an alliance with the Liberals. Its leader, Charles Stewart Parnell convinced William Gladstone to introduce the First Irish Home Rule Bill in 1886. Immediately an Ulster Unionist Party was founded and organized violent demonstrations in Belfast against the bill, fearing that separation from the United Kingdom would bring industrial decline and religious intolerance. Randolph Churchill proclaimed: the Orange card is the one to play, and that: Home Rule is Rome Rule. The "Orange Card" refers to the Protestants, who identify themselves as heirs of William III of England or William of Orange who defeated the deposed Catholic James II of England at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

Although the bill was defeated, Gladstone remained undaunted and introduced a Second Irish Home Rule Bill in 1893 that, on this occasion, passed the Commons. Accompanied by similar massed Unionist protests, Joseph Chamberlain called for a (separate) provincial government for Ulster even before the bill was rejected by the House of Lords. The seriousness of the situation was highlighted when Irish Unionists throughout the island assembled conventions in Dublin and Belfast to oppose the bill and the proposed partition.[7]

When in 1910 the Irish Party again held the balance of power in the Commons, Herbert Asquith introduced a Third Home Rule Bill in 1912. The unheeded Unionist protests of 1886 and 1893 flared up as before, not unexpectedly. With the protective veto of the Lords removed, Ulster armed their Ulster Volunteers in 1913 to oppose enactment of the bill and what they called its "Coercion of Ulster," threatening to establish a Provisional Ulster Government. Nationalists and Republicans remained disinterested in Unionist's concerns, brushed aside their defiance as bluff, saying that Ulster would have no choice except to follow.

Background 1914-1922

The Home Rule Act reached the statute books with Royal Assent in September 1914 but was suspended on the outbreak of World War I for one year or for the duration of what was expected to be a short war. Originally intended to grant self-government to the entire island of Ireland as a single jurisdiction under Dublin administration, the final version as enacted in 1914 included an amendment clause for six Ulster counties to remain under London administration for a proposed trial period of six years, yet to be finally agreed. This was belatedly conceded by John Redmond leader of the Irish Party as a compromise in order to pacify Ulster Unionists and avoid civil war, but was never intended to imply permanent partition.

After the Great War Lloyd George tasked the Long Committee to implement Britain’s commitment to introduce Home Rule which was based on the policy of Walter Long, the findings of the Irish Convention and the new principles of self-determination applied at the Paris Peace Conference. Meanwhile in Ireland, nationalists won the overwhelming majority of the seats in the 1918 (United Kingdom) parliamentary election and declared unilaterally an independent (all-island) Irish Republic. Britain refused to accept the secession and the Irish War of Independence followed. These events together resulted in the enactment of a Fourth Home Rule Act, the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which created two Home Rule parliaments: a Parliament of Northern Ireland which functioned and a Parliament of Southern Ireland which did not. The Anglo-Irish Treaty established a de jure basis for an Irish Free State and allowed the Parliament of Northern Ireland to opt out. Both sides ratified the treaty and Northern Ireland promptly exercised its right to remain within the United Kingdom. Oddly, although the North did opt out, the North never really wanted a separate state at all but wanted the whole island of Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom.

Provision was made in the 1920 Act for a Council of Ireland that would work towards uniting the two parliaments within 50 years (effectively by 1971). This became defunct following the election results in the Free State in May 1921, and was dissolved in 1925. Irish ratification of the Treaty was highly contentious and led directly to the Irish Civil War.

Some Irish nationalists have argued that, when the Irish Free State was founded on 6 December 1922, it included Northern Ireland until the latter voted to remain separate; which it did on 7 December. This theory could appear to make Northern Ireland technically a part of the Free State for a day, but this ignores the divisions aroused by the Anglo-Irish War and by the prior existence of the northern parliament. Further, it was acknowledged and regretted in the Dáil Treaty Debates (December 1921-January 1922) that the Treaty only covered the part of Ireland that became the Free State; the Treaty was ratified by the Dáil, and accepted by the Third Dáil elected in 1922. Others theorize that, had it not opted out in 1922, Northern Ireland could have become a self-governing part of the Free State; a prospect likely to be impractical and unwelcome to both nationalists and unionists. By December 1922 the Free State was also involved in a civil war, and its future direction appeared uncertain.

In any case, opinion of Northern Ireland Unionists had hardened during the Anglo-Irish War. This had caused hundreds of deaths in Ulster, a boycott in the south of goods from Belfast, and re-ignition of inter-sectarian conflict. Following the Truce of July 1921 between the Irish Republican Army and the British Government, these attacks continued. In early 1922, despite a conciliatory meeting between Michael Collins and James Craig, Collins covertly continued his support for the IRA in Northern Ireland. Attacks on Catholics in the north by loyalist mobs in 1920-1922 worsened the situation as did attacks on Protestants in the south. Long's solution of two states on the island largely seemed to reflect the reality on the ground: there was already a complete breakdown of trust between the unionist élite in Belfast and the leaders of the then-Irish Republic in Dublin.

Boundary Commission 1922-1925

The Anglo-Irish Treaty contained a provision that would establish a boundary commission, which could adjust the border as drawn up in 1920. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-Treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down, and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. In the event, the commission's decision was delayed until 1925 by the Irish Civil War and it opted to retain the status quo. The report of the Commission (and thus the terms of the agreement) has yet officially to be made public: the detailed article explains the factors believed to have been involved.

The Dáil voted to approve the Commission's decision, by a supplementary Act, on December 10, 1925 by a vote of 71 to 20.

Partition and sport

Following partition many social and sporting bodies divided. Notably the Irish Football Association of affiliated soccer clubs founded in 1880 split when the clubs in the southern counties set up the "Irish Free State Football Association" in 1921-1936, which was then renamed the Football Association of Ireland. Both are members of FIFA.

However the Irish Rugby Football Union (founded in 1879) continues to represent that game on an all-Ireland basis, organizing international matches and competitions between all four provinces. An element in the growth of Irish nationalism, the Gaelic Athletic Association was formed in 1884 and its sports are still based on teams that represent Ireland's 32 counties.

Partition and rail transport

Rail transport in Ireland was seriously affected by partition. The railway network on either side of the Border relied on cross-border routes, and eventually a large section of the Irish railway's route network was shut down. Today only the cross-border route from Dublin to Belfast remains, and counties Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Monaghan, Tyrone and most of Londonderry have no rail services.

1937 Constitution: Ireland/Éire

De Valera came to power in Dublin in 1932 and drafted a new Constitution of Ireland which in 1937 was adopted by referendum in the Irish Free State. It accepted partition only as a temporary fact and the irredentist articles 2 and 3 defined the 'national territory' as: 'the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas'. The state itself was officially renamed 'Ireland' (in English) and 'Éire' (in Irish), but became referred to casually in the United Kingdom as "Eire" (sic).

To unionists in Northern Ireland, the 1937 constitution made the ending of partition even less desirable than before. Most were Protestants, but article 44 recognized the 'special position' of the Roman Catholic Church. All spoke English but article 8 stipulated that the new 'national language' and 'first official language' was to be Irish, with English as the 'second official language'.

The Constitution was approved only by the electorate of the Free State, and by a relatively slim majority of about 159,000 votes. Considering the Unionist vote in the following year, it is debated by historians whether the Constitution would have been approved by an all-Ireland 32-county electorate.

Decades later the text giving a 'special position' to the Roman Catholic Church was deleted in the Fifth Amendment of 1973. The irrendentist texts in Articles 2 and 3 were deleted by the Nineteenth Amendment in 1998, as part of the Belfast Agreement.

British offer of unity in June 1940

However, during the Second World War, after the invasion of France, Britain made a qualified offer of Irish unity in June 1940, without reference to those living in Northern Ireland. The revised final terms were signed by Neville Chamberlain on June 28, 1940 and sent to Éamon de Valera. On their rejection, neither the London or Dublin governments publicized the matter.

Ireland/Éire would effectively join the allies against Germany by allowing British ships to use its ports, arresting Germans and Italians, setting up a joint defense council and allowing overflights.

In return, arms would be provided to Éire and British forces would cooperate on a German invasion. London would declare that it accepted 'the principle of a United Ireland' in the form of an undertaking 'that the Union is to become at an early date an accomplished fact from which there shall be no turning back.'[8]

Clause ii of the offer promised a Joint Body to work out the practical and constitutional details, 'the purpose of the work being to establish at as early a date as possible the whole machinery of government of the Union'.

The proposals were first published in 1970 in a biography of de Valera.[9]

1945-1973

In May 1949 the Taoiseach John A. Costello introduced a motion in the Dáil strongly against the terms of the UK Republic of Ireland Act 1949 that confirmed partition for as long as a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland wanted it, styled as the Unionist Veto. This was a change from his position supporting the Boundary Commission back in 1925, when he was a legal adviser to the Irish government. A possible cause was that his coalition government was supported by the strongly republican Clann na Poblachta. From this point on, all the political parties in the Republic were formally in favor of ending partition, regardless of the opinion of the electorate in Northern Ireland.

The new Republic could not and in any event did not wish to remain in the Commonwealth and it chose not to join NATO when it was founded in 1949. These decisions broadened the effects of partition but were in line with the evolving policy of Irish neutrality.

In 1966 the Taoiseach Seán Lemass visited Northern Ireland in secrecy, leading to a return visit to Dublin by Terence O'Neill; it had taken four decades to achieve such a simple meeting. The impact was further reduced when both countries joined the European Economic Community in 1973. With the onset of The Troubles (1969-1998) a 1973 referendum showed that a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland did want to continue the link to Britain, as expected, but the referendum was boycotted by Nationalist voters.

Possibility of British withdrawal in 1974

Following the start of the Troubles in Northern Ireland in 1969, the Sunningdale Agreement was signed by the Irish and British governments in 1973. This collapsed in May 1974 due to the Ulster Workers Council Strike, and the new British Prime Minister Harold Wilson considered a rapid withdrawal of the British army and administration from Northern Ireland in 1974-1975 as a serious policy option.

The effect of such a withdrawal was considered by Garret FitzGerald, the Foreign Minister in Dublin, and recalled in his 2006 essay.[10] The Irish cabinet concluded that such a withdrawal would lead to widescale civil war and a greater loss of life, which the Irish Army of 12,500 men could do little to prevent.

Repeal of the Union by the Dáil in 1983

Despite the ongoing dispute about partition, the original Acts of Union which merged Ireland and Britain into a United Kingdom from the start of 1801 have only been repealed in part. The British Act was repealed by the Irish Statute Law Revision Act 1983, a delay of 61 years. The Irish parliament's Act of 1800 was still not repealed in the last Revision Act of 2005; this was described in the Dáil committee debates as a "glaring omission".[11] However, it may be better understood as reflecting the fact that the Parliament of the United Kingdom cannot legally repeal an Act of another parliament, the historic Parliament of Ireland, which itself has not existed since 1801.

Constitutional acceptance in 1998

In the 1937 Constitution of Ireland, Articles 2 and 3 declared that the "territory of the state is the island of Ireland, its outlying islands and its seas." Clearly, this was not the case in fact or in law, as determined by the terms of the Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921. This claim to the territory of Northern Ireland was deeply resented by its majority Unionist population. However, a part of the Belfast Agreement (1998), the Irish government agreed to propose an amendment to Irish Constitution and campaign in its favor in the necessary referendum. This, the Nineteenth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland, changed Articles 2 and 3 was approved by a very large majority. Article 3 now states that "a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island. "

Legacy

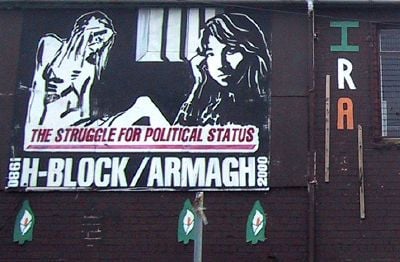

Northern Ireland became a Protestant dominated state, systematically discriminating against Catholics. This led to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s followed by the outbreak of violent rebellion as Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups competed with each other to achieve their goals. Republicans, mainly Catholic, want union with Southern Ireland. Loyalists, mainly Protestant, want to maintain the status quo. Sir James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland from its foundation in 1921 until 1940 described the Northern Ireland Parliament as a Protestant parliament for a Protestant state.[12] Comparisons have been made between the ease with which the departing colonial power opted for partition in Ireland and in India. In both cases, creating discord between the two communities concerned had itself been part of British colonial policy, the divide and rule polity. The "logic of partition was the same" in both cases, says Bennett, "two distinct communities refused to live in peace together in a common space, so that space would be divided into two."[13] In both cases, too, minorities were created on either side of the border resulting in subsequent claims of discrimination, persecution, as well as violence.

The decision to partition Palestine has parallels with Northern Ireland. Just as Britain had created interests in Ireland by encouraging Protestant settlement, so Britain and other European states encouraged Jewish migration to Palestine from the late nineteenth century because the presence of Jews from Europe there with strong ties to their home countries would increase Europe's political influence in the Middle East. When Britain supported the idea of a "national home for the Jewish people" in the Balfour Declaration of 1917 it had in mind a client state. Under the British Mandate, it became increasingly clear that if a Jewish homeland was to be created this would have to be paralleled by the creation of an Arab state. Palestine would have to be Partitioned, based on population density just like India and Ireland. When the United Nations voted in November 1947, the resolution was to Partition Palestine, not to create a single Jewish majority state.[14] The international community also turned to "partition" to deal with competing nationalisms in Bosnia after the collapse of Yugoslavia. Does the international community turn too enthusiastically and too quickly towards partition instead of exploring such possibilities as power-sharing, confederacy and other mechanisms for ensuring that minority rights are protected, that all citizens enjoy equal rights? In Northern Ireland and Bosnia, power-sharing systems have been established to try to address the concerns of the different, formerly rival communities in such areas as civil rights, employment and participation in governance.

Notes

- ↑ Clinton Bennett, In Search of Solutions: The problem of religion and conflict (London, UK: Equinox Pub., 2008, ISBN 9781845532390), 52.

- ↑ Joshua 23:7-13.

- ↑ Bennett, 65.

- ↑ Anglo-Irish Treaty, December 6, 1921. Belfast: Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland (CAIN). Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ↑ 1922. Northern Ireland Parliamentary Debates.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Arthur S. Quekett, The constitution of Northern Ireland (Belfast, IE: H.M.S.O., 1928), 59.

- ↑ Patrick Maume, The Long Gestation: Irish nationalist life, 1891-1918 (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 1999, ISBN 978-0717127443), 10.

- ↑ A. O'Day and J. Stevenson (eds.) Irish Historical Documents since 1800 (Dublin, IE: Gill & Macmillan, 1992, ISBN 0717118398), 201.

- ↑ Earl of Longford and T.P. O'Neill, Éamon de Valera (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1974, ISBN 9780395121016), 365-368.

- ↑ Garret FitzGerald, The 1974-5 Threat of a British Withdrawal from Northern Ireland Irish Studies in International Affairs 17 (2006): 141-150.

- ↑ Statute Law Revision (pre-1922) Act, 2005 Houses of the Oireachtas. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ↑ Bennett, 76.

- ↑ Bennett, 159.

- ↑ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181, November 29, 1947 The Avalon project. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Clinton. In Search of Solutions: The problem of religion and conflict. Religion and violence. London, UK: Equinox Pub., 2008. ISBN 9781845532390

- Cleary, Joe. Literature, Partition and the Nation-state Culture and Conflict in Ireland, Israel and Palestine. (Cultural margins, 10). Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0521651509

- Earl of Longford and T.P. O'Neill. Éamon de Valera. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1974. ISBN 9780395121016

- Fraser, T.G. Partition in Ireland, India, and Palestine: theory and practice. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1984. ISBN 9780312597528

- Hennessey, Thomas. Dividing Ireland: World War I and partition. London, UK: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 9780415174206

- Lynch, Robert John. The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition, 1920-1922. Dublin, IE: Irish Academic Press, 2006. ISBN 9780716533771

- Mansbach, Richard W. Northern Ireland: Half a century of partition. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc., 1973. ISBN 9780871961822

- Mansergh, Nicholas. The Prelude to Partition: Concepts and aims in Ireland and India. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1978. ISBN 9780521221993

- Maume, Patrick. The Long Gestation: Irish nationalist life, 1891-1918. Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 1999. ISBN 978-0717127443

- O'Day, A., and J. Stevenson (eds.). Irish Historical Documents since 1800. Dublin, IE: Gill & Macmillan,1992. ISBN 0717118398

- O'Halloran, Clare. Partition and the Limits of Irish Nationalism: An ideology under stress. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International, 1987. ISBN 9780391035027

- Quekett, Arthur S. The Constitution of Northern Ireland. Belfast, IE: H.M.S.O., 1928.

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- James Connolly: Labour and the Proposed Partition of Ireland (Marxists Internet Archive).

- HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND (History World).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.