Paleocene

The Paleocene is a geologic epoch that lasted from 65.5 ± 0.3 million years ago (mya) to 55.8 ± 0.2 mya. It is the first epoch of the Paleogene period in the modern Cenozoic era, and is followed by the Eocene. As with most other older periods of the geologic time scale, the strata that define the Paleocene epoch's beginning and end are well identified, but the exact dates are uncertain.

The Paleocene has traditionally has been viewed as the first epoch of the prominent Tertiary period, but the International Commission on Stratigraphy no longer endorses this term (nor Quaternary) and instead recommends the Paleogene and Neogene periods as the primary subdivisions of the Cenozoic era. When used, the Tertiary is often considered as a sub-era that includes part of the Paleogene and part of the Neogene.

The Paleocene was "bookended" by dramatic events: A mass extinction (the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event) and a rapid global warming (the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum). The die-off of the dinosaurs in the prior mass extinction left unfilled ecological niches worldwide, and the name "Paleocene" comes from Greek and refers to the "old(er) (paleo)–new (ceno)" fauna that arose during the epoch, prior to the emergence of modern mammalian orders in the Eocene. The Paleocene provided the foundation for today, including the appearance of primate-like mammals.

| Cenozoic era (65-0 mya) | |

|---|---|

| Paleogene | Neogene Quaternary |

| Tertiary sub-era | ||

|---|---|---|

| Paleogene period | ||

| Paleocene epoch | Eocene epoch | Oligocene epoch |

| Danian | Selandian Thanetian |

Ypresian | Lutetian Bartonian | Priabonian |

Rupelian | Chattian |

Paleocene boundaries and subdivisions

The Paleocene epoch immediately followed the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous, known as the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event or K-T extinction event. Many forms of life perished, encompassing approximately 50 percent of all plant and animal families, the most conspicuous being the non-avian dinosaurs. Some now recognize this mass extinction as occurring at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary rather than the K-T boundary, because of the new recommended classification (Hinton 2006).

The K-T boundary that marks the separation between Cretaceous and Paleocene is visible in the geological record of much of the Earth by a discontinuity in the fossil fauna, with high iridium levels. There is also fossil evidence of abrupt changes in plants and animals. There is some evidence that a substantial but very short-lived climatic change may have occurred in the very early decades of the Paleocene. There are a number of theories about the cause of the K-T extinction event, with most evidence supporting the impact of a 10 kilometer diameter asteroid near Yucatan, Mexico.

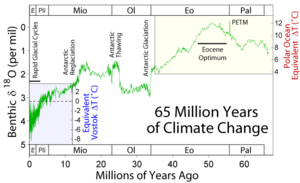

The end of the Paleocene (55.5/54.8 mya) was marked by one of the most significant periods of global change during the Cenozoic, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. In an event marking the start of the Eocene, the planet heated up in one of the most rapid and extreme global warming events recorded in geologic history, currently either the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum or the Initial Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM or IETM). Sea surface temperatures rose between 5 and 8°C over a period of a few thousand years, but in the high Arctic, sea surface temperatures rose to a sub-tropical ~23°C/73°F. This upset oceanic and atmospheric circulation and led to the extinction of numerous deep-sea benthic foraminifera and on land, a major turnover in mammals.

The Paleocene is usually broken into early, middle, and late sub-epochs, which correspond to the following faunal stages (divisions based on fossils), from youngest to oldest:

| Thanetian | (58.7 ± 0.2–55.8 ± 0.2 mya) |

| Selandian | (61.7 ± 0.2–58.7 ± 0.2 mya) |

| Danian | (65.5 ± 0.3–61.7 ± 0.2 mya) |

Paleocene climate

According to the science of paleoclimatology, the early Paleocene is considered to have been slightly cooler than the preceding Cretaceous, though temperatures rose again late in the epoch. The climate was warm and humid worldwide, with subtropical vegetation growing in Greenland and Patagonia. The poles were cool and temperate, North America, Europe, Australia, and southern South America were warm and temperate; tropical climates characterized equatorial areas, and north and south of the Equator, climates were hot and arid (Scotese 2002).

Paleocene paleogeography

In many ways, the Paleocene continued processes that had begun during the late Cretaceous period. During the Paleocene, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. North America and Asia were still intermittently joined by a land bridge, while Greenland and North American were beginning to separate (Hooker 2005). The Laramide orogeny of the late Cretaceous continued to uplift the Rocky Mountains in the American west, only ending in the succeeding epoch.

South and North America remained separated by equatorial seas, joining later, during the Neogene. The components of the former southern supercontinent, Gondwana, continued to split apart, with Africa, South America, Antarctica, and Australia pulling away from each other. Africa was heading north towards Europe, slowly closing the Tethys Ocean, and India began its migration to Asia that would lead to the huge tectonic collision and formation of the Himalayas.

The inland seas in North America (Western Interior Seaway) and Europe had receded by the beginning of the Paleocene, making way for new land-based flora and fauna.

Paleocene flora

Terrestrial Paleocene strata immediately overlying the K-T boundary is, in places, marked by a "fern spike:" a bed especially rich in fern fossils (Vajda 2004). Ferns are often the first species to colonize areas damaged by forest fires; thus the fern spike may indicate post-Chicxulub devastation (Bigelow 2005).

In general, the Paleocene is marked by the development of modern plant species. Cacti and palm trees appeared. Paleocene and later plant fossils are generally attributed to modern genera, or to closely related taxa.

The warm temperatures worldwide gave rise to thick tropical, sub-tropical, and deciduous forest cover around the globe (the first recognizably modern rainforests), with ice-free polar regions covered with coniferous and deciduous trees (Hooker 2005). With no large grazing dinosaurs to thin them, Paleocene forests were probably denser than those of the Cretaceous.

Flowering plants (angiosperms), first seen in the Cretaceous, continued to develop and proliferate, coevolving with the insects that fed on these plants and pollinated them.

Paleocene fauna

Mammals

Mammals had first appeared in the Triassic, and developed alongside the dinosaurs. They appear to have exploited ecological niches untouched by the larger and more famous Mesozoic animals: The insect-rich forest underbrush and high up in the trees. These smaller mammals (as well as birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects) survived the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, which wiped out the dinosaurs. Mammals diversified and spread throughout the world.

While early mammals were seemingly small, nocturnal animals with herbivorous and insectivorous diets, the demise of the dinosaurs and the beginning of the Paleocene saw mammals growing larger, more ferocious, and finally becoming the dominant predators, spreading throughout the world. Ten million years after the death of the dinosaurs, the world was filled with rodent-like mammals, medium sized mammals scavenging in forests, and large herbivorous and carnivorous mammals hunting other mammals, birds, and reptiles.

Paleocene mammals do not seem to have specialized teeth or limbs, and their brain to body mass ratios appear to have been quite low. Compared to later forms, they are considered primitive, or archaic (Kazlev 2002). It was not until the Eocene, 55 mya, that true modern mammals developed.

Jehle (2006) notes that it is in the early Paleocene that fossil evidence of animals with strong links to the primates appears. Interestingly, these primate-like forms are found on the European and North American continents—regions largely not inhabited by primates today. This may be explained by the warm climates that extended into the north during the Paleocene.

Fossil evidence from the Paleocene is scarce, and there is relatively little known about mammals of the time. Because of their small size—a constant until late in the epoch—early mammal bones are not well-preserved in the fossil record, and most of what paleontologists know comes from fossil teeth (a much tougher substance), and only a few skeletons (Hooker 2005).

Mammals of the Paleocene include:

- Monotremes. Three species of monotremes are represented in modern times: The duck-billed platypus, and two species of Echidnas. Monotrematum sudamericanum lived during the Paleocene.

- Marsupials. A number of marsupials are represented in modern times, such as the kangaroos, which are characterized by giving birth to embryonic babies, who crawl into the mother's pouch and suckle until they are developed. The Pucadelphys andinus is a Paleocene example of a marsupial.

- Multituberculates. This is the only major branch of mammals to go extinct. This rodent-like grouping includes the Paleocene Ptilodus.

- Placentals. This grouping of mammals became the most diverse and the most successful. Members include hoofed ungulates, primates, and carnivores, such as the Paleocene mesonychid.

Reptiles

Due to the climatic conditions of the Paleocene, [[reptile]s] were more widely distributed over the globe than at present. Among the sub-tropical reptiles found in North America during this epoch are champsosaurs (aquatic reptiles that resemble modern gharials), crocodilians, soft-shelled turtles, palaeophid snakes, varanid lizards, and Protochelydra zangerli (similar to modern snapping turtles).

Examples of champsosaurs of the Paleocene include Champsosaurus gigas, the largest champsosaur ever discovered. This creature was unusual among Paleocene reptiles in that C. gigas became larger than its known Mesozoic ancestors: C. gigas is more than twice the length of the largest Cretaceous specimens (3 meters versus 1.5 meters). Reptiles as a whole decreased in size after the K-T event. Champsosaurs declined towards the end of the Paleocene and became extinct at the end of the Eocene.

Examples of Paleocene crocodilians are the euschian crocodilid Leidyosuchus formidabilis, the apex predator and the largest animal of the Wannagan Creek fauna, and the alligatorid Wannaganosuchus.

Dinosaurs may have survived to some extent into the early Danian stage of the Paleocene Epoch, circa 64.5 mya. The controversial evidence for such is a hadrosaur leg bone found from Paleocene strata from 64.5 mya in Australia.

Birds

Birds began to diversify during the epoch, occupying new niches. Most modern bird types had appeared by mid-Cenozoic, including perching birds, cranes, hawks, pelicans, herons, owls, ducks, pigeons, loons, and woodpeckers.

Large, carnivorous, flightless birds (also called Terror Birds) have been found in late Paleocene fossils, including the fearsome Gastornis in Europe.

Early owl types such as Ogygoptynx and Berruornis appear in the late Paleocene.

Paleocene oceans

Warm seas circulated throughout the world, including the poles. The earliest Paleocene featured a low diversity and abundance of marine life, but this trend reversed later in the epoch (Hooker 2005). Tropical conditions gave rise to abundant marine life, including coral reefs. With the demise of marine reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous, sharks became the top predators. The end of the Cretaceous also saw extinctions of the ammonites, and many species of foraminifera.

Marine faunas also came to resemble modern faunas, with only the marine mammals and the Charcharinid sharks missing.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bigelow, P. 2005. The K-T Boundary In The Hell Creek Formation. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Jehle, M. 2006. Primate-like Mammals: A Stunning Diversity in the Tree Tops. Paleocene Mammals of the World website. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Hinton, A. C. 2006. Saving Time. BlueSci Online. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Hooker, J. J. 2005. Tertiary to present: Paleocene. In R. C. Selley, L. R. McCocks, and I. R. Plimer, Encyclopedia of Geology, Vol. 5, pp. 459-465. Oxford: Elsevier Limited. ISBN 0-12-636380-3

- Kazlev, M. A. 2002. The Paleocene. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Ogg, J. 2004. Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's).Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Scotese, C. R. 2002. PaleoMap Project: Paleocene Climate. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Vajda, V. 2004. Global Disruption of Vegetation at the Cretaceous-Tertiary Boundary: A Comparison Between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere Palynological Signals. Geological Society of America. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Vajda, V., J. I. Raine, and C. J. Hollis. 2001. Indication of global deforestation at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary by New Zealand fern spike. Science 294: 1700-1702.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.