Pope Julius I

| Julius I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Julius |

| Papacy began | February 6, 337 |

| Papacy ended | April 12, 352 |

| Predecessor | Mark |

| Successor | Liberius |

| Born | ??? Rome, Italy |

| Died | April 12, 352 Rome, Italy |

| Other popes named Julius | |

Pope Saint Julius I (Unknown – April 12, 352), was pope from February 6, 337 to April 12, 352. Julius is chiefly known by the part he took in the Arian controversy and for bolstering the role of the papacy as the defender of "orthodoxy" in the face of changing imperial politics.

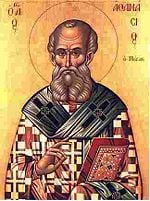

Living during a period of shifting attitudes by the Roman emperors who had only recently begun showing special favor to Christianity, Julius supported the anti-Arian leader Athanasius of Alexandria in his struggle against the patriarch of Constantinople, Eusebius of Nicomedia. Banished for a second time from Alexandria, Athanasius was welcomed to Rome, where he was accepted as a legitimate bishop by a synod presided over by Julius in 342. Julius' subsequent letter to the Eastern bishops represents an early instance of the claims of primacy for the bishop of Rome.

It was also through the influence of Julius that the Council of Sardica was held a few months later. The council did not succeed in uniting the eastern and western bishops in support of the restoration of Athanasius and other anti-Arian leaders, and its 76 eastern bishops withdrew to Philippopolis where they went so far as to adopt an Arian creed and to excommunicate Julius and his supporters. However, some 300 western bishops remained in place at Sardica and confirmed the decisions of the previous Roman synod, as well as affirming the pope's authority.

Julius died on April 12, 352, and was succeeded by Liberius. He is considered a saint in both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions, with his feast day on April 12.

Biography

Background

The long reign of Pope Silvester I had been followed by the brief papacy of Pope Mark. After Mark's death, the papal chair remained vacant for four months. What occasioned this comparatively long vacancy is unknown, although it is worth noting that serious controversy now raged over the continuing Arian controversy, which had been by no means settled at the Council of Nicaea in 325. The Liber Pontificalis reports that, before coming to the papacy, Julius had suffered exile as a result of the Arianizing policy of the emperors, although this report is not entirely trusted by scholars.

On February 6, 337, Julius was finally elected pope. A native of Rome, he was the son of a man named Rusticus.

Support of Athanasius

During the reign of Constantine the Great, the anti-Arian patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria had been banished after Constantine became persuaded that his previous policy of attempting to suppress Arianism was unwise. After the emperor's death in May 337, his son Constantine II, as governor of Gaul, permitted Athanasius to return to his see of Alexandria. An opposing party in Egypt, however, recognized a rival bishop in the person of Pistus. They sent a delegation to Julius asking him to admit Pistus into communion with Rome, also delivering to the pope the decisions of the Council of Tyre (335) to prove that Athanasius had been validly deposed.

For his part, Athanasius sent envoys to Rome to deliver to Julius a conciliar letter from certain other Egyptian bishops, containing a justification of Athanasius as their patriarch. The two opposing delegations were summoned by Pope Julius for a hearing. The anti-Athanasian envoys now asked the pope to assemble a major council, before which both parties should present their case for decision.

Julius convened the synod at Rome, having dispatched two envoys to bear a letter of invitation to the eastern bishops. In the meantime, under the leadership of Eusebius of Nicomedia, the patriarch of Constantinople, a council had been held at Antioch which had elected George of Cappadocia as patriarch of Alexandria in the place of both Pistus and Athanasius. George was duly installed at Alexandria over the violent objections of the supporters of Athanasius, who was now once again forced into exile.

Believing the matter to be settled, the other eastern bishops consequently refused to attend the synod summoned by Julius. Rome, meanwhile, became a refuge for Athanasius and other anti-Arian leaders, among them Marcellus of Ancyra, who had been removed by the pro-Arian party. The Roman council was held in the autumn of 340 or 341, under the presidency of the pope. After Athanasius and Marcellus both made satisfactory professions of faith, they were exonerated and declared to be re-established in their episcopal rights. Julius communicated this decision in a notable letter to the bishops of the Eusebian party in the East, in which he justified his proceedings and strongly objected to the refusal of the Eastern bishops to attend the Roman council. Even if Athanasius and his companions were somewhat to blame in their actions, the pope admitted, the Alexandrian church should first have written to the pope before taking action against them. "Can you be ignorant," Julius wrote, "that this is the custom, that we should be written to first, so that from here what is just may be defined?"

The Council of Sardica

Meanwhile, the political tide had turned for the moment in the pope's direction. Constantine's son Constans had defeated his brother Constantine II, and was now ruler over the greater part of the Roman Empire. He favored the Nicaean party over that of Eusebius of Nicomedia. At the request of the pope and other western bishops, Constans interceded with his brother Constantius II, the emperor of the East, in favor of the bishops who had been deposed by the Eusebian party. Both rulers agreed that there should be convened an ecumenical council of the Western and Eastern bishops at Sardica (the modern Sofia, Bulgaria).

The Council of Sardica took place in the autumn of 342 or 343, Julius sending as his representatives the priests Archidamus and Philoxenus and the deacon Leo. However, the eastern bishops, sensing that they were outnumbered, soon departed and held a separate synod in Philippopolis. The western council then proceeded to confirm Athanasius' innocence and also established regulations for the proper procedure against accused bishops, including recognition of the supreme authority of the pope.

In Philippopolis, the eastern bishops anathematized the term homoousios ("same substance," referring to the relationship of God the Son to God the Father), which had been adopted at Nicaea against the Arians, and excommunicated Julius I together with their rivals at the Council in Sardica. They also introduced the new term anomoian ("not similar"), going further even than the Arian party had at Nicaea in affirming a difference in substance between Christ and God the Father.

Later years

However, Constantius II declined to restore Athanasius until after the death of George, Athanasius' rival, in 346. Pope Julius took this occasion to write a letter, which is still extant, to the priests, deacons, and the faithful of Alexandria, to congratulate them on the return of their pastor. At this time two bishops who had been deposed by the Council of Sardica, Ursacius of Singidunum and Valens of Mursia, formally recanted the formerly Arian views before Julius, who then restored to them their episcopal sees. Despite these accomplishments, Julius' policy of support for Athanasius still did not prevail, as Constantius II pursued an increasingly aggressive policy of accommodation with Arianism.

Legacy

Julius died on April 12, 352, and was buried in the catacombs of Calepodius on the Aurelian Way. Very soon after his death, was honored as a saint. His body was later transported to the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

Although he had hoped that the council of Sardica would be recognized as an ecumenical council, the schism which took place there only perpetuated and exacerbated the Arian controversy. Constantius II's policy of attempting to force the Nicene party to accept communion with moderate Arians would have the upper hand for the next decade. However, Julius' pro-Athanasian actions ultimately proved important to the victory of Nicene Christianity and the defeat of Arianism at the First Council of Constantinople in 381.

During the pontificate of Julius, there was a rapid increase in the number of Christians in Rome, where Julius had two new basilicas erected: the titular church of Julius (now Santa Maria in Trastevere) and the Basilica Julia (now the Church of the Twelve Apostles). Beside these he built three churches over cemeteries outside the walls of Rome: one on the road to Porto, a second on the Via Aurelia, and a third on the Via Flaminia at the tomb of the martyr Saint Valentine. The ruins of the last-mentioned were discovered in the nineteenth century.

The practice of venerating the saints at the tombs of the martyrs also continued to spread rapidly during Julius' day. Under his pontificate, if not earlier, catalogs of feast-days of saints came into use. For example the Roman feast-calendar of Philocalus dates from the year 336.

Several of Julius’ letters are preserved in Athanasius’ work, Apology Against the Arians. Also through Athanasius, who remained in Rome several years subsequent to 339, the tradition of Egyptian monastic life became well-known in the capital, and the example of the hermits of the Egyptian deserts found many imitators in the Roman church and later western tradition.

The feast day of Saint Julius I is celebrated on April 12.

| Roman Catholic Popes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Mark |

Bishop of Rome Pope 337–352 |

Succeeded by: Liberius |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the Catholic Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- Chapman, John. Studies on the Early Papacy. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1971. ISBN 9780804611398

- Duffy, Eamon. Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0300091656

- Fortescue, Adrian, and Scott M.P. Reid. The Early Papacy: To the Synod of Chalcedon in 451. Southampton: Saint Austin Press, 1997. ISBN 9781901157604

- Kelly, John N.D., and Michael J. Walsh. The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2005. ISBN 9780198614333

- Loomis, Louise Ropes. The Book of Popes (Liber Pontificalis). Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1889758868

- Maxwell-Stuart, P.G., and Toby A. Wilkinson. Chronicle of the Popes: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Papacy from St. Peter to the Present. W.W. Norton & Co Inc, 1997. ISBN 9780500017982

| ||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.