Quinine

| |

| |

Quinine

| |

| Systematic name | |

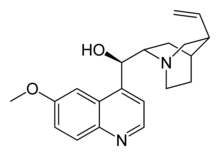

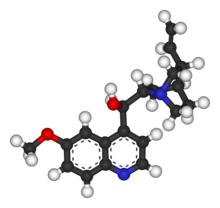

| IUPAC name (2-ethenyl-4-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-yl)- (6-methoxyquinolin-4-yl)-methanol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 130-95-0 |

| ATC code | M09AA01 P01BC01 |

| PubChem | 8549 |

| DrugBank | APRD00563 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C20H24N2O2 |

| Mol. weight | 324.417 g/mol |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 177°C (351°F) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 76 to 88% |

| Protein binding | ~70% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (mostly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Half life | ~18 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (20%) |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | X (USA), D (Au) |

| Legal status | ? |

| Routes | Oral, intravenous |

Quinine is a natural, bitter-tasting crystalline alkaloid derived from the bark of various cinchona species (genus Cinchona) and having antipyretic (fever-reducing), anti-smallpox, analgesic (painkilling), and anti-inflammatory properties. It has been used for hundreds of years for the treatment and prevention of malaria and continues to be used today.

Quinine is an example of the many medicinal values in the natural environment. As an effective agent to treat malaria, quinine has probably benefited more people than any other drug in the combat of infectious disease (CDC 2000). For a long time, it was the only agent to treat malaria. In addition, human creativity has uncovered numerous other uses for this natural substance, including treating leg cramps and arthritis and inducing uterine contractions during childbirth, as well as such non-medical uses as a flavor component of tonics and other drinks.

Overview: Description, sources

Quinine has the chemical formula C20H24N2O2. It is a stereoisomer of quinidine, a pharmaceutical agent that acts as a class I antiarrhythmic agent in the heart. (Stereoisomers are molecules with the same chemical formula and whose atomic connectivity is the same but whose atomic arrangement in space is different.)

The natural source of quinine are various species in the genus Cinchona, which are large evergreen shrubs or small trees native to tropical South America. The name of the genus is due to Linnaeus, who named the tree in 1742 after a Countess of Chinchon, the wife of a viceroy of Peru, who according to legend, was cured by the medicinal properties of the bark after introduction to this source by natives. Stories of the medicinal properties of this bark, however, are perhaps noted in journals as far back as the 1560s-1570s. The medicinally active bark, which is stripped from the tree, dried and powdered, includes other alkaloids that are closely related to quinine but react differently in treating malaria. As a medicinal herb, cinchona bark is also known as Jesuit's bark or Peruvian bark. The plants are cultivated in their native South America, and also in other tropical regions, notably in India and Java.

Quinine was extracted from the bark of the South American cinchona tree and was isolated and named in 1817 by French researchers Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou. The name was derived from the original Quechua (Inca) word for the cinchona tree bark, "Quina" or "Quina-Quina," which roughly means "bark of bark" or "holy bark." Prior to 1820, the bark was first dried, ground to a fine powder and then mixed into a liquid (commonly wine), which was then drunk.

Cinchona trees remain the only practical source of quinine. However, under wartime pressure, research towards its artificial production was undertaken during World War II. A formal chemical synthesis was accomplished in 1944 by American chemists R.B. Woodward and W.E. Doering (Woodward and Doering 1944). Since then, several more efficient quinine total syntheses have been achieved, but none of them can compete in economic terms with isolation of the alkaloid from natural sources. Quinine is available with a prescription in the United States.

History of use with malaria

The theorized mechanism of action for quinine and related anti-malarial drugs is that these drugs are toxic to the malaria parasite. Specifically, the drugs interfere with the parasite's ability to break down and digest hemoglobin. Consequently, the parasite starves and/or builds up toxic levels of partially degraded hemoglobin in itself.

Quinine was the first effective treatment for malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum, appearing in therapeutics in the seventeenth century.

The legend, perhaps anecdotal, says that the first European ever to be cured from malaria fever was the wife of the Spanish Viceroy, the countess of Chinchon. The court physician was summoned and urged to save the countess from the wave of fever and chill which was proving fatal for her. Every effort failed to relieve her from this ailed condition. At last the court physician collected a medicine from the local Indians that grew on the Andes mountain slopes. They had been using this medicine for similar syndromes. The medicine was given to her and surprisingly she survived the malarial attack. When she returned to Europe in the 1640s, she reportedly brought the bark with her.

Quinine was first used to treat malaria in Rome in 1631. During the 1600s, malaria was endemic to the swamps and marshes surrounding the city of Rome. Over time, malaria was responsible for the death of several Popes, many Cardinals, and countless common citizens of Rome. Most of the priests trained in Rome had seen malaria victims and were familiar with the shivering brought on by the cold phase of the disease. In addition to its anti-malarial properties, quinine is an effective muscle relaxant, long used by the Quechua Indians of Peru to halt shivering brought on by cold temperatures. The Jesuit Brother Agostino Salumbrino (1561-1642), an apothecary by training and who lived in Lima, observed the Quechua using the quinine-containing bark of the cinchona tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was entirely unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from cold, it was still the correct medicine for malaria. At the first opportunity, he sent a small quantity to Rome to test in treating malaria. In the years that followed, cinchona bark became one of the most valuable commodities shipped from Peru to Europe.

Charles II called upon Mr. Robert Talbor, who had become famous for his miraculous malaria cure. Because at that time the bark was in religious controversy, Talbor gave the king the bitter bark decoction in great secrecy. The treatment gave the king complete relief from the malaria fever. In return, he was offered membership of the prestigious Royal College of Physicians.

In 1679, Talbor was called by the King of France, Louis XIV, whose son was suffering from malaria fever. After a successful treatment, Talbor was rewarded by the king with 3,000 gold crowns. At the same time he was given a lifetime pension for this prescription. Talbor was requested to keep the entire episode secret. Known henceforth as Chevalier Talbot, he became famous throughout Europe, curing hundreds of other royal and aristocratic persons, including Louis XIV and Queen Louisa Maria of Spain (CDC 2000).

After the death of Talbor, the French king found this formula: Six drahm of rose leaves, two ounces of lemon juice, and a strong decoction of the chinchona bark served with wine. Wine was used because some alkaloids of the cinchona bark are not soluble in water, but soluble in wine.

Large scale use of quinine as a prophylaxis started around 1850. Quinine also played a significant role in the colonization of Africa by Europeans.

Quinine remained the antimalarial drug of choice until the 1940s, when other drugs took over. Since then, many effective antimalarials have been introduced, although quinine is still used to treat the disease in certain critical situations, such as resistance developed by certain strains of parasite to another anti-malarial, chloroquine.

The birth of homoeopathy was based on quinine testing. The founder of homoeopathy, Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, when translating the Cullen's Materia medica, noticed that Dr. Cullen wrote that quinine cures malaria and can also produce malaria. Dr. Hahnemann took daily a large non-homeopathic dose of quinine bark. After two weeks, he said he felt malaria-like symptoms. This idea of "like cures like" was the starting point of his writing on "Homoeopathy."

Non-malarial uses of quinine

In addition to treating malaria, quinine is also used to treat nocturnal leg cramps and arthritis, and there have been attempts (with limited success) to treat prion diseases. Quinine also has been used to induce uterine contractions during childbirth, as a schlerosing agent, and to treat myotonia congenita and atrial fibrillation.

In small amounts, quinine is a component of various drinks. It is an ingredient of tonic drinks, acting as a bittering agent. These may be added to alcoholic drinks. Quinine also is a flavor component of bitter lemon, and vermouth. According to tradition, the bitter taste of anti-malarial quinine tonic led British colonials in India to mix it with gin, thus creating the gin and tonic cocktail, which is still popular today in many parts of the world. In France, quinine is an ingredient of an apéritif known as Quinquina. In Canada, quinine is an ingredient in the carbonated chinotto beverage called Brio. In the United Kingdom, quinine is an ingredient in the carbonated and caffeinated beverage, Irn-Bru.

Quinine is often added to street drugs cocaine or ketamine in order to "cut" the product and make more profit. It was once a popular heroin adulterant.

Because of its relatively constant and well-known fluorescence quantum yield, quinine is also used in photochemistry as a common fluorescence standard.

Dosing

Quinine is a basic amine and is therefore always presented as a salt. Various preparations that exist include the hydrochloride, dihydrochloride, sulfate, bisulfate, and gluconate. This makes quinine dosing very complicated, because each of the salts has a different weight.

The following amounts of each form are equal:

- quinine base 100 mg

- quinine bisulfate 169 mg

- quinine dihydrochloride 122 mg

- quinine hydrochloride 122 mg

- quinine sulfate 121 mg

- quinine gluconate 160 mg.

All quinine salts may be given orally or intravenously (IV); quinine gluconate may also be given intramuscularly (IM) or rectally (PR) (Barennes et al. 1996; Barennes et al. 2006). The main problem with the rectal route is that the dose can be expelled before it is completely absorbed, but this can be rectified by giving a half dose again.

The IV dose of quinine is 8 mg/kg of quinine base every eight hours; the IM dose is 12.8 mg/kg of quinine base twice daily; the PR dose is 20 mg/kg of quinine base twice daily. Treatment should be given for seven days.

The preparations available in the UK are quinine sulfate (200 mg or 300 mg tablets) and quinine hydrochloride (300 mg/ml for injection). Quinine is not licensed for IM or PR use in the UK. The adult dose in the UK is 600 mg quinine dihydrochloride IV or 600 mg quinine sulfate orally every eight hours.

In the United States, quinine sulfate is available as 324 mg tablets under the brand name Qualaquin; the adult dose is two tablets every eight hours. There is no injectable preparation of quinine licensed in the U.S.: quinidine is used instead (CDC 1991; Magill and Panosian 2005).

Quinine is not recommended for malaria prevention (prophylaxis) because of its side effects and poor tolerability, not because it is ineffective. When used for prophylaxis, the dose of quinine sulphate is 300–324mg once daily, starting one week prior to travel and continuing for four weeks after returning.

Side effects

Cinchonism or quinism is a pathological condition in humans caused by an overdose of quinine or its natural source, cinchona bark. Cinchonism can occur from therapeutic doses of quinine, either from one or several large doses, or from small doses over a longer period of time, not from the amounts used in tonic drinks, but possibly from ingestion of tonic water as a beverage over a lengthy period of time. Quinidine can also cause cinchonism.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration limits tonic water quinine to 83 parts per million, which is one-half to one-quarter the concentration used in therapeutic tonic.

It is usual for quinine in therapeutic doses to cause cinchonism; in rare cases, it may even cause death (usually by pulmonary oedema). The development of mild cinchonism is not a reason for stopping or interrupting quinine therapy and the patient should be reassured. Blood glucose levels and electrolyte concentrations must be monitored when quinine is given by injection; the patient should also ideally be in cardiac monitoring when the first quinine injection is given (these precautions are often unavailable in developing countries where malaria is most a problem).

Cinchonism is much less common when quinine is given by mouth, but oral quinine is not well tolerated (quinine is exceedingly bitter and many patients will vomit up quinine tablets): other drugs such as Fansidar® (sulfadoxine (sulfonamide antibiotic) with pyrimethamine) or Malarone® (proguanil with atovaquone) are often used when oral therapy is required. Blood glucose, electrolyte and cardiac monitoring are not necessary when quinine is given by mouth.

In 1994, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the use of over-the-counter (OTC) quinine as a treatment for nocturnal leg cramps. Pfizer Pharmaceuticals had been selling the brand name Legatrin® for this purpose. This was soon followed by disallowing even prescription quinine for leg cramps, and all OTC sales of the drug for malaria. From 1969 to 1992, the FDA received 157 reports of health problems related to quinine use, including 23 which had resulted in death (FDA 1995).

Quinine can cause paralysis if accidentally injected into a nerve. It is extremely toxic in overdose and the advice of a poisons specialist should be sought immediately.

Quinine and pregnancy

In very large doses, quinine also acts as an abortifacient (a substance that induces abortion). In the United States, quinine is classed as a Category X teratogen by the Food and Drug Administration, meaning that it can cause birth defects (especially deafness) if taken by a woman during pregnancy. In the United Kingdom, the recommendation is that pregnancy is not a contra-indication to quinine therapy for falciparum malaria (which directly contradicts the US recommendation), although it should be used with caution; the reason for this is that the risks to the pregnancy are small and theoretical, as opposed to the very real risk of death from falciparum malaria. Further research, conducted in Sweden's Consug University hospital, has found a weak but significant correlation between dosage increase in pregnancy and Klebs-Loeffler bacillus infections in neonates.

Quinine and interactions with other diseases

Quinine can cause hemolysis in G6PD deficiency, but again this risk is small and the physician should not hesitate to use quinine in patients with G6PD deficiency when there is no alternative. Quinine can also cause drug-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).

Quinine can cause abnormal heart rhythms and should be avoided if possible in patients with atrial fibrillation, conduction defects or heart block.

Quinine must not be used in patients with hemoglobinuria, myasthenia gravis or optic neuritis, because it worsens these conditions.

Quinine and hearing impairment

Some studies have related the use of quinine and hearing impairment, which can cause some high-frequency loss, but it has not been conclusively established whether such impairment is temporary or permanent (DCP 1994).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barennes, H., et al. 1996. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of a new intrarectal quinine formulation in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Brit J Clin Pharmacol 41: 389.

- Barennes, H., T. Balima-Koussoubé, N. Nagot, J.-C. Charpentier, and E. Pussard. 2006. Safety and efficacy of rectal compared with intramuscular quinine for the early treatment of moderately sever malaria in children: randomised clinical trial. Brit Med J 332 (7549): 1055-1057.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). 1991. Treatment with quinidine gluconate of persons with severe Plasmodium falciparum infection: Discontinuation of parenteral quinine. Morb Mort Weekly Rep 40(RR-4): 21-23. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2000. Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age. The cure. Emerg Infect Dis 6(1). Medscape article. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Department of Clinical Pharmacology (DCP), Huddinge University Hospital, Sweden. 1994. The concentration-effect relationship of quinine-induced hearing impairment. Clin Pharmacol Ther 55(3): 317-323. PMID 8143397.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1995. FDA orders stop to marketing Of quinine for night leg cramps. FDA. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Magill, A., and C. Panosian. 2005. Making antimalarial agents available in the United States. New Engl J Med 353(4): 335-337.

- Woodward, R., and W. Doering. 1944. The total synthesis of quinine. Journal of the American Chemical Society 66(849).Category:Biochemistry]]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.