Ram Mohan Roy

Ram Mohan Roy, also written as Rammohun Roy, or Raja Ram Mohun Roy (Bangla: রাজা রামমোহন রায়, Raja Rammohon Rae), (May 22, 1772 – September 27, 1833) was the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, one of the first Indian socio-religious reform movements. He turned to religious reform after a career in the service of the British East India Company and as a private moneylender. His remarkable influence was apparent in the fields of politics, public administration and education as well as religion. He is most known for his efforts to abolish the practice of sati, a Hindu funeral custom in which the widow sacrifices herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. He is credited with first introducing the word "Hinduism" (or "Hindooism") into the English language in 1816. For many years, he enjoyed a close relationship with William Carey and the Baptist missionaries at Serampore. Under his influence, one of the missionaries converted to Unitarianism. Roy corresponded with eminent Unitarians and died while staying as the guest of the Unitarian minister in Bristol, England, who preached at his funeral.

In 1828, prior to his departure to England, Rammohan founded, with Dwarkanath Tagore, the Brahmo Samaj, which came to be an important spiritual and reformist religious movement that has given birth to a number of leaders of the Bengali social and intellectual reforms. From 1821 until 1828 he had been associated with the Calcutta Unitarian Association, which he co-founded. For several years, Roy funded Unitarian publications in Calcutta. However, he thought that Indians would feel more comfortable staying within their own culture, and eventually withdrew his from the Unitarian mission although he still maintained cordial relations with its members and leaders. He also disagreed with use of Bengali for worship (insisting on Sanksrit, Persian or English). He may have been the first Brahmin to travel to England and to be buried there. For his contributions to society, Raja Ram Mohan Roy is regarded as one of the most important figures in the Bengal Renaissance. In 1829, he was awarded the title Rajah by the Moghul Emperor. Roy has been dubbed the "father of modern India" [1]

Early life and education

Roy was born in Radhanagore, Bengal, in 1772. His family background displayed an interesting religious diversity. His father Ramkant was a Vaishnavite, while his mother Tarini was from a Shakta background. Rammohan learnt successively Bangla, Persian, Arabic and Sanskrit by the age of fifteen.

As a teenager, Roy became dissatisfied with the practices of his family, and travelled widely, before returning to manage his family property. On his travels, he may have visited India. He also spent some time studying at Varanasi, the great center of Hindu learning. He then worked as a moneylender in Calcutta, and from 1803 to 1814 was employed by the British East India Company. At the age of 42, he had accumulated sufficient wealth to devote himself full-time to religious pursuits and to social reform. Exposure to the preaching of Christian missionaries and to their denunciation of Indian religion and culture as polytheistic, superstitious, idolatrous and irrational led him to re-examine that tradition. Roy's monotheistic ideas were formed as early as 1804, when he published his Persian tract Tuhfat' ul muhwahhiddin (A Gift to Monotheists). Roy's study of the Upanishads had convinced him that Hinduism taught the existence of a single God, or Absolute Reality and that the development of the many deities, and of venerating their images, was a corruption of originally monotheistic Hinduism. In 1816 he founded a Friendly Society to promote the discussion of his religious ideas. At about this time he was prosecuted by members of his family who wanted to have his property confiscated on the grounds that he was a Hindu apostate. Christian accused him of heresy; some Hindus saw him as a modernizing atheist who was bent on destroying ancient customs and practices. Roy consciously responded to Christian criticism of Hinduism but he was convinced that what they criticized were in fact corruptions of what he saw as an originally pure monotheism. Pure Hinduism, too, for him was an ethical, not an immoral, religion. Critical of the Vedas, he preferred the Upanishads. God could be known through nature. There is no need of images to depict God.

Exposure to Christianity

In the early 1820s, Roy assisted the Baptists at Serampore in their work of Bible translation. He worked closely with several missionaries, including a missionary from Scotland, William Adam (1796-1881), who had arrived in India in 1818 and had studied Bengali and Sanskrit in order to join the translation team. He was already making common cause with them in their campaign against Sati (widow sucide on their husband's funeral pyre), since his own sister-in-law committed Sati in 1812. From this period, Roy also championed gender-equality. In 1821, while working on the prologue to John's Gospel, Roy found himself arguing with the missionaries about the meaning of the Greek "dia," which the senior missionaries wanted to translate as "by" ("by Him all things were made"). Adam sided with Roy in preferring "through" ("through Him all things were made"), and shortly resigned from the Mission to become a Unitarian. Adam thought that Unitarianism might have a wider appeal in India that orthodox Christianity. William Ward one of the leaders of the Serampore Baptiss saw Adam's defection as a victory for Satan; "he lived in a country which Satan had made his own to a degree that allowed as a final blow a missionary to be converted to heathenism." "A missionary! O Lord," he declaimed, "How have we fallen." [2]. Adam, who still saw himself as "Christian" [3] agreed with Roy that "through" made Jesus subordinate to God, an agent of God, which he thought more acceptable theologically than "by" which made Jesus into an independent entity and compromise monotheism.

Roy on Jesus

In 1920, Roy published his book on Jesus, The Precepts of Jesus. He depicted Jesus as a great teacher of ethics, whose will was in harmony with the will of God. However, he denied Jesus' divinity, just as he denied the existence of avatars or human manifestation of the divine in Hinduism. He also extracted miracles from the gospels, since these contravened reason. One of the senior Baptists, Joshua Marshman repudiated Roy's book in his A Defence of the Deity and Atonement of Jesus Christ, in reply to Ram-mohun Roy of Calcutta ([4] to which Roy responded with his Appeal to the Christian Public in Defense of the Precepts of Jesus By A Friend of Truth. Controversy with Marshman generated a further two such Appeals.

Roy and the Unitarians

In 1822, William Adam, with financial help from Roy and later from Unitarian in the United States and Britain, formed the Calcutta Unitarian Society. Roy also funded the Society's printing press. However, although he identified Unitarianism as closer to the ethical-monotheism he espoused, he wanted to ground his religious ideas in the cultural context of India. Roy corresponded with some eminent Unitarians at this period. When Roy withdrew funding in 1828 to set up his own society, the Brahmo Samaj, Adam found employment writing a major report on education for the Indian government. Later, he served several Unitarian congregations in North America but is said to have repudiated Unitarianism before his death [5].

Founder of the Brahmo Samaj

While remaining sympathetic to Unitarianism, which he thought closer to his own ideas of ethical monotheism than the Christianity of the Baptist, he wanted to reform Hinduism from inside. To pursue this agenda, with the support of Dwarkanath Tagore, he established the Brahmo Samaj in 1828. This Society advocated monotheism, or the worship of one God, repudiated denounced rituals, which its members deemed meaningless and based on superstitions, crusaded against social evils like sati and polygamy and in favor of property inheritance rights for women. It also repudiated the traditional role of the priestly class. Initially, the Samaj was more of an organization to promote social reform than a religious one. Later, especially under the leadership of Debendranath Tagore it became a spiritual home where Indians could practice an ethical monotheism stripped of superstition but within an Indian cultural context.

Mainly due to Roy's efforts, Governor General William Bentinck made sati illegal through an act in 1829.

Educator

Roy was committed to education, without which he believed social reform would be impossible. He campaigned for education in Western science and technology combined with India's heritage. In 1822, he established an English medium Anglo-Hindu School and in 1827, with the support of the Scottish missionary-educator Alexander Duff he founded the Anglo-Hindu College. In the social, legal and religious reforms that he advocated, Roy was moved primarily by considerations of humanity. He took pains to show that his aim was not to destroy the best traditions of the country, but merely to brush away some of the impurities that had gathered on them in the days of decadence. He respected the Upanishads and studied the Sutras. He condemned idolatry in the strongest terms. He stated that the best means of achieving bliss was through pure spiritual contemplation and worship of the Supreme Being, and that sacrificial rites were intended only for persons of less subtle intellect.

Roy campaigned for the rights of women, including the right of widows to remarry and the right of women to hold property. As mentioned above, he actively opposed polygamy, a system in which he had grown up.

He believed that English-language education was superior to the traditional Indian education system, and he opposed the use of government funds to support schools teaching Sanskrit. He championed women's education.

Family

Rammohun had three wives before the age of ten. His first wife died in childhood. He had two sons, Radhaprasad, born 1800, and Ramaprasad, born 1812, with his second wife, who died in 1824. He was survived by his third wife.

Journalist and Writer

Roy published journals in English, Hindi, Persian and Bengali. His most popular journal was the Samvad Kaumudi. It covered topics like freedom of press, induction of Indians into higher ranks of service, and separation of the executive and judiciary.

He published several works of translation from the Vedas and Upanishads, including Translation of Several Principal Books, Passages, and Texts of the Vedas (1832).

Late Life

In 1831 Ram Mohan Roy travelled to the United Kingdom as an ambassador of the Mughal Emperor, who created him a Rajah in 1829, to ensure that that Lord Bentick's law banning the practise of Sati was not overturned [6]. He also visited France. While in England he also campaigned on behalf of the 1832 Reform Act, which extended the franchize (although not to women) and abolished such corrupt practices as "rotton boroughs" whose MPs were more or less the personal appointees of patrons. He thought the Act a step in the right direction, that is, towards democracy.

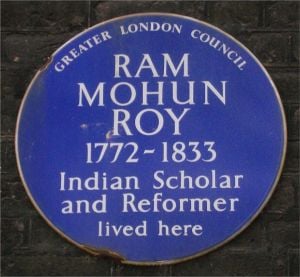

He died at Stapleton then a village to the north east of Bristol (now a suburb) on the 27th September 1833 of meningitis while visiting the home of the local Unitarian minister, Lance Carpenter and is buried in Arnos Vale Cemetery in southern Bristol. A statue of him was erected in College Green, Bristol in 1997. He is said to have died with the sacred syllable "Om" on his breath [7]. There is also a blue plaque commemorating him on his house in Bedford Square, London.

Tomb

The tomb built in 1843, located in the Arnos Vale Cemetery on the outskirts of Bristol, is in need of considerable restoration and repair. It was built by Dwarkanath Tagore in 1843, ten years after Rammohun Roy's death due to meningitis in Bristol on Sep 27, 1833.

In September 2006 representatives from the Indian High Commission came to Bristol to mark the anniversary of Ram Mohan Roy's death, during the ceremony Hindu, Muslim and Sikh women sang Sanskrit prayers of thanks [8].

Following on from this visit the Mayor of Kolkata, Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya (who was amongst the representatives from the India High Commission) decided to raise funds to restore the tomb.

In June 2007 businessman Aditya Poddar donated £50,000 towards the restoration of his grave after being approached by the Mayor of Kolkata for funding. [9].

Epitaph

The epitaph on the late nineteenth century stone at the tomb reads: "Beneath this stone rest the remains of Raja Rammohun Roy Bahadur, a conscientious and steadfast believer in the unity of Godhead, he consecrated his life with entire devotion to the worship of the Divine Spirit alone.

"To great natural talents, he united through mastery of many languages and distinguished himself as one of the greatest scholars of his day. His unwearied labour to promote the social, moral and physical condition of the people of India, his earnest endeavours to suppress idolatry and the rite of suttie and his constant zealous advocacy of whatever tended to advance the glory of God and the welfare of man live in the grateful remembrance of his countrymen."

Legacy

Ram Monan Roy was a major shaper of modern India. Consciosuly influenced by Christianity and by the social agenda of many missionaries as much if not more than by their religious ideas, he was convinced that India's culture and religious tradition was rational and of profound spiritual value. Nehru describes Roy as a "new type" of thinker "combining in himself the old learning and the new." "Deeply versed," wrote Nehru, "in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanksrit, Persian and Arabic, he was a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture" of that part of India. Nehru cites Oxford's second Boden Professor of Sanskrit, Sir Monier-Monier Williams on Roy as the world's first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion [10]. While he remained rooted in Hinduism, Roy admired much of what he saw in Islam, Christianity and in other religions which he studied, and believed that the same fundamental truths inform all of them. He held that the first principle of all religions is the "Absolute Originator." Against the criticism that it contained very little of lasting worth, he set out to retrieve from India's heritage what could withstand the scrutiny of a rational mind. He went further than others in what he was prepared to abandon, which for him included the Vedas. For other reformers, such as Dayananda Saraswati, the Vedas contained all religious truth as well as ancient scientific knowledge, and were not to be thrown away. The organization he founded, the Brahmo Samaj, was a pioneer of social reform, an important promoter of education and of India's autonomy and eventual independence. Its basic ideals, including gender-equality and its rejection of class-based privilege, have become part of the social framework of Indian society, at least in theory.

See also

- Brahmo Samaj

Notes

- ↑ "Ram Mohun Roy," Encyclopedia Britannica online online Ram Mohun Roy Retrieved September 17, 2007

- ↑ Potts, 214

- ↑ Ibid., 239

- ↑ London: Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen, 1822

- ↑ Hill, Andrew "William Adam" Unitarian Universalist Historical Society William Adam Retrieved September 18, 2007

- ↑ Roy, Amit "New Life for Rajah's Tomb." The Telegraph (Calcutta) June 14, 2007 The Telegraph (Calcutta) - New life for Raja’s tomb Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Marilyn Richards, and Peter Hughes, "Rammohun Roy" Unitarian Universalist Historical Society Rammohun Roy Retrieved September 18, 2007

- ↑ "City service honours humanitarian," BBC 24 September 2006 BBC News - City service honours humanitarian Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ "£50k restoration for Indian tomb," BBC 12 June, 2007 BBC News - £50k restoration for Indian tomb Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Nehru, 315

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahluwalia, Shashi & Meenakshi AhluwaliaRaja. Rammohun Roy and the Indian renaissance. New Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1991. ISBN 8170992397

- Chandra, Rama Prasad and J.K. Majumdar. Selections from official letters and documents relating to the life of Raja Rammohun Roy. Delhi: Anmol Publications, 1987. ISBN 8170410673

- Crawford, S. Cromwell. Ram Mohan Roy: Social, Political, and Religious Reform in 19th Century India. New York: Paragon House, 1987. ISBN 9780913729151

- Nehru, Jawahaelal. The Discovery of India. Calcutta: Signett Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. (original 1946) ISBN 0195623592

- Potts, E. Daniel. British Baptist Missionaries in India, 1793-1837: The History of Serampore and Its Missions. London: Cambridge University Press, 1967. ISBN 052105978X

- Roy, Rammohun and Mulk Raj Anand. Sati, a Writeup of Raja Ram Mohan Roy About Burning of Widows Alive. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp, 1989. ISBN 9788170185352

- __________. The Precepts of Jesus. Boston: Christian Record Agency, 1828

- __________. An Appeal to the Christian Public. NY: B. Bates, 1825.

- Sankhdher, Brijendra Mohan. Rammohan Roy, the Apostle of Indian Awakening: Some Contemporary Estimates. New Delhi: Navarang, 1989. ISBN 9788170130512

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.