Roger Williams

| Roger Williams | |

| |

| Born | c.1603 |

|---|---|

| Died | April 19 1683 (aged 79) |

| Occupation | minister, author |

| Religious beliefs | Baptist, Seeker |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Barnard |

Roger Williams (c.1603 – April 1, 1683) was an English theologian and leading American colonist, an early and courageous proponent of the separation of church and state, an advocate for fair dealings with Native Americans, founder of the city of Providence, Rhode Island, and co-founder of the colony of Rhode Island. He was also one of the the founders of the Baptist church in America.

A religious separatist, Williams questioned the right of the colonists to take the Native American lands merely on the legal basis of the royal charter, and he raised other objections to the ruling Massachusetts religious authorities. As a result, in 1635, he was banished from the colony.

During his 50 years in New England, the English theologian contributed to the developing religious landscape of America. Williams went well beyond his separatist predecessors by advocating and providing religious freedom for others—not only those who agreed with his teachings. The "lively experiment" of the Rhode Island colony framed a government that protected the individual "liberty of conscience" and, in doing so, established a precedent for religious freedoms guaranteed in the later United States Constitution.

For much of his later life, Williams was engaged in polemics on political and religious questions, condemning the orthodoxy of New England Puritanism and attacking the theological underpinnings of Quakerism.

Biography

Early life

Roger Williams was born in London, England around 1603 to James Williams (1562-1620), a merchant in Smithfield, England, and Alice Pemberton (1564-1634). Under the patronage of the jurist Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634), Williams was educated at Sutton's Hospital and at the University of Cambridge, Pembroke College (B.A., 1627). He had a gift for languages and acquired familiarity with Latin, Greek, Dutch, and French. Interestingly, he gave the poet John Milton lessons in Dutch in exchange for lessons in Hebrew.

After graduating from Cambridge, Williams became chaplain to a wealthy family. He married Mary Barnard (1609-1676) on December 15, 1629 at the Church of High Laver, Essex, England. They had six children, all born after their emigration to America.

Before the end of 1630, Williams decided that he could not work in England under Archbishop William Laud's rigorous (and High church) administration, and adopted a position of dissent. He turned aside offers of preferment in the university and in the established church, and instead resolved to seek a greater liberty of conscience in New England.

Removal to America

In 1630, Roger and Mary Williams set sail for Boston on the Lyon. Arriving on February 5, 1631, he was almost immediately invited to replace the pastor, who was returning to England. Finding that it was "an unseparated church"—Puritan yet still aligned with the Church of England—Williams declined, instead giving voice to his growing Separatist views. Among these, Williams asserted that the magistrate may not punish any sort of "breach of the first table [of the Ten Commandments]," such as idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, false worship, and blasphemy. He held that every individual should be free to follow his own convictions in religious matters.

Williams' first argument—that the magistrate should not punish religious infraction—meant that the civil authority should not be the same as the ecclesiastical authority. His second argument-—that people should have freedom of opinion on religious matters-—he called "soul-liberty." It is one of the foundations for the United States Constitution's guarantees of non-establishment of religion and of freedom to choose and practice one's own religion. Williams' use of the phrase "wall of separation" in describing his preferred relationship between religion and other matters is credited as the first use of that phrase, and potentially, Thomas Jefferson's source in later speaking of the wall of separation between church and state (Feldman 2005, 24)

The Salem church, which through interaction with the Plymouth colonists had also adopted Separatist sentiments, invited Williams to become its teacher. His settlement there was prevented, however, by a remonstrance addressed to Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endicott by six of the Boston leaders. The Plymouth colony, which was not under Endicott's jurisdiction, then received him gladly, where he remained for about two years. According to Governor William Bradford, who had come to Plymouth on the Mayflower, "his teachings were well approved."

Life at Salem, Exile

Toward the close of his ministry at Plymouth, however, Williams' views began to place him in conflict with other members of the colony, as the people of Plymouth realized that his ways of thinking, particularly concerning the Indians, were too liberal for their tastes; and he left to go back to Salem.

In the summer of 1633, Williams arrived in Salem and became unofficial assistant to Pastor Samuel Skelton. In August 1634, Skelton having died, Williams became acting pastor and entered almost immediately into controversies with the Massachusetts authorities. Brought before the court in Salem for spreading "diverse, new, and dangerous opinions" that questioned the Church, Williams was sentenced to exile.

An outline of the issues raised by Williams and uncompromisingly pressed includes the following:

- He regarded the Church of England as apostate, and any kind of fellowship with it as grievous sin. He accordingly renounced communion not only with this church but with all who would not join with him in repudiating it.

- He denounced the charter of the Massachusetts Company because it falsely represented the King of England as a Christian and assumed that the King had the right to give to his own subjects the land of the native Indians.

- Williams' was opposed to the "citizens' oath," which magistrates sought to force upon the colonists in order to be assured of their loyalty. This opposition gained considerable popular support so that the measure had to be abandoned.

- In a dispute between the Massachusetts Bay court and the Salem colony regarding the possession of a piece of land (Marblehead), the court offered to accede to the claims of Salem on the condition that the Salem church remove Williams as its pastor. Williams regarded this proposal as an outrageous attempt at bribery and had the Salem church send to the other Massachusetts churches a denunciation of the proceeding and a demand that the churches exclude the magistrates from membership. The magistrates and their supporters, however, were able to successfully pressure the Salem church to remove Williams. He never entered the chapel again, but held religious services in his own house with his faithful adherents until his exile.

Settlement at Providence

In June 1635, Williams arrived at the present site of Providence, Rhode Island. Having secured land from the natives, he established a settlement with 12 "loving friends and neighbors," several settlers having joined him from Massachusetts. Williams' settlement was based on a principle of equality. It was provided that "such others as the major part of us shall admit into the same fellowship of vote with us" from time to time should become members of their commonwealth. Obedience to the majority was promised by all, but "only in civil things" and not in matters of religious conscience. Thus, a government unique in its day was created—a government expressly providing for religious liberty and a separation between civil and ecclesiastical authority (church and state).

The colony was named Providence, due to Williams' belief that God had sustained him and his followers and brought them to this place. When he acquired the other islands in the Narragansett Bay, Williams named them after other virtues: Patience Island, Prudence Island, and Hope Island.

In 1637, some followers of the antinomian teacher Anne Hutchinson visited Williams to seek his guidance in moving away from Massachusetts. Like Williams, this group was in trouble with the Puritan authorities. He advised them to purchase land from the Native Americans on Aquidneck Island and they settled in a place called Pocasset, now the town of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Among them were Anne Hutchinsons's husband William, William Coddington, and John Clarke.

In 1638, several Massachusetts credobaptists—those who rejected infant baptism in favor of "believer's baptism"—had found themselves subject to persecution and moved to Providence. Most of these had probably known Williams and his views while he was in Massachusetts, while some may have been influenced by English Baptists before they left England.

However, Williams did not adopt Baptist views before his banishment from Massachusetts, for opposition to infant baptism was not charged against him by his opponents. About March 1639, Williams was re-baptized himself and then immediately proceeded to re-baptize 12 others. Thus was constituted a Baptist church which still survives as the First Baptist Church in America. At about the same time, John Clarke, Williams’ compatriot in the cause of religious freedom in the New World, established a Baptist church in Newport, Rhode Island. Both Williams and Clarke are thus credited as being the founders of the Baptist faith in America.

Williams remained with the little church in Providence only a few months. He assumed the attitude of a "Seeker," in the sense that although he was always deeply religious and active in the propagation of Christian faith, he wished to remain free to choose among a wide variety of diverse religious institutions. He continued on friendly terms with the Baptists, however, being in agreement with them in their rejection of infant baptism as in most other matters.

In 1643, Williams was sent to England by his fellow citizens to secure a charter for the colony. The Puritans were then in power in England, and through the offices of Sir Henry Vane a democratic charter was obtained. In 1647, the colony of Rhode Island was united with Providence under a single government, and liberty of conscience was again proclaimed. The area became a safe haven for people who were persecuted for their beliefs. Baptists, Quakers, Jews, and others went there to follow their consciences in peace and safety. Significantly, on May 18, 1652, Rhode Island passed the first law in North America making slavery illegal.

Death and internment

Williams died in early 1684 and was buried on his own property. Some time later in the nineteenth century his remains were moved to the tomb of a descendant in the North Burial Ground. Finally, in 1936, they were placed within a bronze container and put into the base of a monument on Prospect Terrace Park in Providence. When his remains were discovered for reburial, they were under an apple tree. The roots of the tree had grown into the spot where Williams' skull rested and followed the path of his decomposing bones and grew roughly in the shape of his skeleton. Only a small amount of bone was found to be reburied. The "Williams Root" is now part of the collection of the Rhode Island Historical Society, where it is mounted on a board in the basement of the John Brown House Museum.

Writings

Williams' career as an author began with A Key into the Language of America (London, 1643), written during his first voyage to England. His next publication dealt with issues of citizenship and the powers of civil authority, a reply to a letter of the Massachusetts Puritan leader Reverend John Cotton to British authorities, titled Mr. Cotton's Letter lately Printed, Examined and Answered.

His most famous work, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience soon followed (London 1644). This was his seminal statement and defense of the principle of absolute liberty of conscience. It is in the form of a dialog between Truth and Peace, and well illustrates the vigor of his style.

During the same year an anonymous pamphlet appeared in London which has been commonly ascribed to Williams, entitled: Queries of Highest Consideration Proposed to Mr. Tho. Goodwin, Mr. Phillip Nye, Mr. Wil. Bridges, Mr. Jer. Burroughs, Mr. Sidr. Simpson, all Independents, etc.

In 1652, during his second visit to England, Williams published The Bloudy Tenent yet more Bloudy (London, 1652). This work traverses anew much of the ground covered by the first Bloudy Tenent, but it has the advantage of being written in answer to Cotton's elaborate defense of New England persecution, titled A Reply to Mr. Williams his Examination.

Other works by Williams are:

- The Hireling Ministry None of Christ's (London 1652)

- Experiments of Spiritual Life and Health, and their Preservatives (London 1652; reprinted Providence 1863)

- George Fox Digged out of his Burrowes (Boston 1676)

Legacy

During his 50 years in New England, Williams was a staunch advocate of religious toleration and the separation of church and state. Reflecting these principles, he and his fellow Rhode Islanders framed a colony government devoted to protecting individual "liberty of conscience." This "lively experiment" became Williams' most tangible legacy, though he was best known in his own time as a radical Pietist and the author of polemical treatises defending his religious principles, condemning the orthodoxy of New England Puritanism, and attacking the theological underpinnings of Quakerism.

Williams' death went mostly unnoticed. It was the American Revolution that transformed Williams into a local hero—Rhode Islanders came to appreciate the legacy of religious freedom he had bequeathed to them. Although he has often been portrayed by biographers as a harbinger of Jeffersonian Democracy, most scholars now conclude that Williams was less a democrat than a "Puritan's Puritan" who courageously pushed his dissenting ideas to their logical ends.

Tributes, descendants

- Roger Williams University in Bristol, Rhode Island, is named in his honor.

- Roger Williams National Memorial, established in 1965, is a park in downtown Providence.

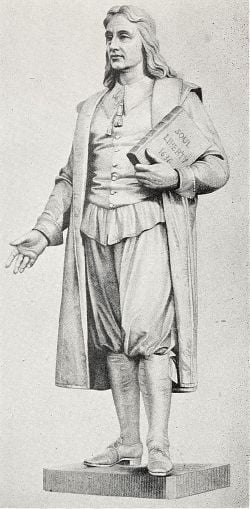

- Williams was selected in 1872 to represent Rhode Island in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol.

- Famous descendants of Roger Williams include: Gail Borden, Julia Ward Howe, Charles Eugene Tefft, Michelle Phillips, and Nelson Rockefeller.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davis, James Calvin. The Moral Theology of Roger Williams: Christian Conviction and Public Ethics. Westminster John Knox Press, 2004. ISBN 9780664227708

- Feldman, Noah. Divided by God. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005. ISBN 0374281319

- Gaustad, Edwin, S. Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America. Judson Press, 1999. ISBN 9780817013387

- Hall, Timothy L. Separating Church and State: Roger Williams and Religious Liberty. University of Illinois Press, 1997. ISBN 9780252066641

- Morgan, Edmund S. Roger Williams: The Church and the State. W.W. Norton, 1997. ISBN 9780393304039

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Roger Williams National Memorial – www.nps.gov

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.