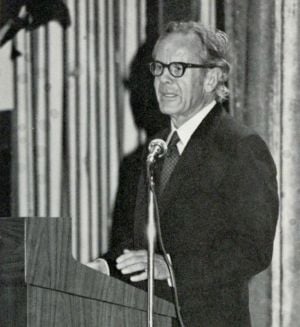

Rollo May

Rollo May (April 21, 1909 - October 22, 1994) was an American existential psychologist. May is often associated with humanistic psychologists such as Abraham Maslow or Carl Rogers, but he relied more on a philosophical model. He was a close friend of the U.S. German-born theologian Paul Tillich. May's works include Love and Will and The Courage to Create, the latter title honoring Tillich's The Courage to Be.

May is best known for his work on the human struggles of living in the modern world. He believed that to successfully handle the trials of life, we must come face to face with such issues as anxiety, loneliness, choice, and responsibility. Like other existential therapists, he argued that it is easier to avoid pain, choice, and responsibility in the world than face them. However, when one avoids the painful parts of life, he becomes alienated from the world, others, and himselfâand as a consequence of the avoidance, feels pain, anxiety, and depression. May advocated facing life's challenges with purpose and meaning, which he called having "true religion," as a path to healing and mental health.

Life

Rollo May was born on April 21, 1909, in Ada, Ohio. He experienced a difficult childhood, with his parents divorcing and his sister suffering a psychotic breakdown. His educational odyssey took him to Michigan State College (where he was asked to leave due to his involvement with a radical student magazine) and Oberlin College, for a bachelor's degree in 1930.

After graduating, he took a position at Anatolia College teaching English in Greece. While there, he often traveled to Vienna to attend seminars by Alfred Adler. He returned to the United States to Union Theological Seminary in New York City for a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1938. There he became friends with one of his teachers, Paul Tillich, the existentialist theologian, who would have a profound effect on his thinking. After graduation, he practiced two years as a Congregationalist minister, then resigned from the ministry and attended Columbia University for a PhD in clinical psychology.

While studying for his doctorate, May experienced a severe illness, tuberculosis, and had to spend three years in a sanatorium. This was a transforming event in his life as he had to face the possibility of death. During this time he spent many hours reading the literature of Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish religious philosopher who inspired much of the existential movement. As a result of this traumatic experience, May developed a new fondness for existential philosophy, which matched his belief that his personal struggle against death, even more than medical care, determined his fate in surviving the disease.

May studied psychoanalysis at the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychoanalysis, where he met people such as Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm. In 1949, he received the first PhD in clinical psychology that Columbia University in New York ever awarded. He held a position as lecturer at the New School for Social Research, as well as visiting, as a professor, at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and other universities.

His first book, The Meaning of Anxiety (1950), was based on his doctoral dissertation, which in turn was based on his reading of Kierkegaard. His definition of anxiety is "the apprehension cued off by a threat to some value which the individual holds essential to his existence as a self."[1] He also quotes Kierkegaard: "Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom." In 1956, he edited the book, Existence, with Ernest Angel and Henri Ellenberger. Existence helped introduce existential psychology to the U.S.

He was the author of numerous influential books, including The Courage to Create, Love and Will, The Meaning of Anxiety, Freedom and Destiny, and Psychology and the Human Dilemma. In recognition of his significant contributions, May was awarded the Distinguished Career in Psychology Award by the American Psychological Association.

He spent the closing years of his life in Tiburon on the San Francisco Bay, where he died in October of 1994.

Work

May was interested in reconciling existential psychology with other approaches, especially Freudian psychoanalysis. Perhaps the central issue that draws existential thinkers together is their emphasis upon the primacy of existence in philosophical questioning and the importance of responsible human action in the face of uncertainty. With complete freedom to decide and be responsible for the outcome of their decisions comes anxiety about the choices humans make. Anxiety's importance in existentialism makes it a popular topic in psychotherapy.

Existentialism in psychotherapy

Therapists often use existential philosophy to explain the patient's anxiety. May did not speak of anxiety as a symptom to be removed, but rather as a gateway for exploration into the meaning of life. Existential psychotherapists employ an existential approach by encouraging their patients to harness their anxiety and use it constructively. Instead of suppressing anxiety, patients are advised to use it as grounds for change. By embracing anxiety as inevitable, a person can use it to achieve his or her full potential in life. In an interview with Jerry Mishlove, May said of anxiety:

What anxiety means is it's as though the world is knocking at your door, and you need to create, you need to make something, you need to do something. I think anxiety, for people who have found their own heart and their own souls, for them it is a stimulus toward creativity, toward courage. It's what makes us human beings.[2]

May was not a mainstream existentialist in that he was more interested in reconciling existential psychology with other approaches, especially Freudâs. May used some traditional existential terms in a slightly different fashion than others, and he invented new words for traditional existentialist concepts. Destiny, for example, could be "thrownness" combined with "fallenness"âthe part of life that is already determined, for the purpose of creating lives. He also used the word "courage" to signify authenticity in facing oneâs anxiety and rising above it.

May described certain "stages" of development:[3]

- Innocenceâthe pre-egoic, pre-self-conscious stage of the infant. The innocent is only doing what he or she must do. However, an innocent does have a degree of will in the sense of a drive to fulfill needs.

- Rebellionâthe rebellious person wants freedom, but has yet no full understanding of the responsibility that goes with it.

- Decisionâthe person is in a transition stage in their life where they need to break away from their parents and settle into the ordinary stage. In this stage they must decide what path their life will take, along with fulfilling rebellious needs from the rebellious stage.

- Ordinaryâthe normal adult ego learned responsibility, but finds it too demanding, and so seeks refuge in conformity and traditional values.

- Creativeâthe authentic adult, the existential stage, beyond ego and self-actualizing. This is the person who, accepting destiny, faces anxiety with courage.

These are not stages in the traditional sense. A child may certainly be innocent, ordinary, or creative at times; an adult may be rebellious. The only attachment to certain ages is in terms of salience: Rebelliousness stands out in the two year old and the teenager.

May perceived the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as commercialization of sex and pornography, as having influenced society, planting the idea in the minds of adults that love and sex are no longer directly associated. According to May, emotion became separated from reason, making it socially acceptable to seek sexual relationships and avoid the natural drive to relate to another person and create new life. May believed the awakening of sexual freedoms can lead modern society to dodge awakenings at higher levels. May suggested that the only way to turn around the cynical ideas that characterized his generation is to rediscover the importance of caring for another, which May describes as the opposite of apathy. For May, the choice to love is one of will and intentionality, unlike the base, instinctive, drive for sexual pleasure. He wrote in Love and Will that instead of surrendering to such impulses, real human existence demanded thought and consideration. To be free would not be to embrace the oxymoron "free love" and the associated hedonism, but to rise above such notions and realize that love demands effort.

Mental health and religion

In his book, The Art of Counseling, May explored the relationship between mental health and religion. He agreed with Freud that dogmatic religion appeals to humanity's neurotic tendencies but diverges from this viewpoint by explaining that true religion, the fundamental affirmation of the meaning of life, is "something without which no human being can be healthy in personality." He noted that what Freud was attacking was the abuse of religion as it is used by some to escape from their life challenges.

May agreed with Carl Jung that most people over 35 would have their problems resolved by finding a religious outlook on life. Jung believed that those patients actually fell ill because they had lost the sense of meaning which living religions of every age have given to their followers, and only those who regained a religious outlook were healed. May believed this is true for people of all ages, not just those over 35; that all people ultimately need to find meaning and purpose, which true religion can provide. He claimed that every genuine atheist with whom he had dealt had exhibited unmistakable neurotic tendencies. May described the transformation, mostly through the grace of God, from neurosis to personality health:

The person rises on the force of hope out of the depths of his despair. His cowardice is replaced by courage. The rigid bonds of his selfishness are broken down by a taste of the gratification of unselfishness. Joy wells up and streams over his pain. And love comes into the man's life to vanquish the loneliness. He has at last found himselfâand found his fellowmen and his place in the universe. Such is the transformation from neurosis to personality health. And such is what it means, likewise, to experience religion.[4]

Legacy

Rollo May was one of the founding sponsors of the Association for Humanistic Psychology, and a genuine pioneer in the field of clinical psychology. May is considered by many to be one of the most important figures in existential psychology, and, without question, one of the most important American existential psychologists in the history of the discipline. He is often called "the father of existential psychotherapy," an amazing accomplishment since existential philosophy originated in Europe and, for the most part, was met with hostility and contempt in the United States. May can be credited as the editor, along with Ernest Angel and Henri F. Ellenberger, of the first American book on existential psychology, Existence, which highly influenced the emergence of American humanistic psychologists (such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow).

Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center and its Rollo May Center for Humanistic Studies celebrate the advancement of the humanistic tradition in psychology and human science by presenting The Rollo May Award. As one of Saybrook's founders, Rollo May exhibited an unflinching trust in the transformative power of love, choice, and creative action. The Rollo May Award recognizes an individual whose life's work demonstrates his faith in human possibility.

Major works

- May, Rollo. [1950] 1996. The Meaning of Anxiety. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-31456-1

- May, Rollo. [1953] 1973. Manâs Search for Himself. Delta ISBN 0-385-28617-1

- May, Rollo. [1956] 1994. Existence. Jason Aronson. ISBN 1-56821-271-2

- May, Rollo. [1965] 1989. The Art of Counseling. Gardner Press. ISBN 0-89876-156-5

- May, Rollo. [1967] 1996. Psychology and the Human Dilemma. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-31455-3

- May, Rollo. [1969] 1989. Love and Will. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-01080-5, Delta. ISBN 0-385-28590-6

- May, Rollo. [1972] 1998. Power and Innocence: A Search for the Sources of Violence. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-31703-X

- May, Rollo. [1975] 1994. The Courage to Create. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-31106-6

- May, Rollo. [1981] 1999. Freedom and Destiny. W W Norton edition: ISBN 0-393-31842-7

- May, Rollo. [1983] 1994. The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-31240-2

- May, Rollo. 1985. My Quest for Beauty. Saybrook Publishing. ISBN 0-933071-01-9

- May, Rollo. [1991] 1992. The Cry for Myth. Delta. ISBN 0-385-30685-7

Notes

- â Rollo May, The Meaning of Anxiety (W W Norton, 1996). ISBN 0393314561

- â Jerry Mishlove, The Human DilemmaâInterview with Rollo May Ph.D. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- â C. George Boeree, Rollo May. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- â Rollo May, The Art of Counseling (Gardner Press, 1989). ISBN 0898761565

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- May, Rollo. [1950] 1996. The Meaning of Anxiety. New York: Ronald Press Co. ISBN 0-393-31456-1

- May, Rollo. [1965] 1989. The Art of Counseling. Gardner Press. ISBN 0-89876-156-5

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.