The tale of the Forty-Seven Ronin, also known as the Forty-Seven Samurai, the Ak┼Ź vendetta, the Ak┼Ź Wandering Samurai (ŔÁĄšęéŠÁ¬ňúź Ak┼Ź r┼Źshi), or the Genroku Ak┼Ź Incident (ňů⚎äŔÁĄšęéń║őń╗ Genroku ak┼Ź jiken), is a prototypical Japanese story. Described by one noted Japan scholar as the country's "national legend" (Izumo), it recounts the most famous case involving the samurai code of honor, Bushid┼Ź.

The story tells of a group of samurai who were left leaderless (became ronin) after their daimyo-master was forced to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) for assaulting a court official named Kira Yoshinaka, whose title was k┼Źzuk├ę-no-suk├ę). The ronin avenged their master's honor after patiently waiting and planning for over a year to kill Kira. In turn, the ronin were themselves forced to commit seppukuÔÇöas they knew beforehandÔÇöfor committing the crime of murder. With little embellishment, this true story was popularized in Japanese culture as emblematic of the loyalty, sacrifice, persistence and honor which all good people should preserve in their daily lives. The popularity of the almost mythical tale was only enhanced by rapid modernization during the Meiji era of Japanese history, when many people in Japan longed for a return to their cultural roots.

Ronin

R┼Źnin (ŠÁ¬ń║║, r┼Źnin) were masterless samurai during the feudal period (1185ÔÇô1868) of Japan. A samurai became masterless from the ruin or fall of his master, or after the loss of his master's favor or privilege. The word r┼Źnin literally means "drifting person." The term originated in the Nara and Heian periods, when it originally referred to serfs who had fled or deserted their master's land. It is also a term used for samurai who had lost their masters in wars.

According to the Bushido Shoshinshu (the Code of the Samurai), a ronin was supposed to commit oibara seppuku (also "hara kiri" ÔÇô ritual suicide) upon the loss of his master. One who chose to not honor the code was "on his own" and was meant to suffer great shame. The undesirability of ronin status was mainly a discrimination imposed by other samurai and by the daimyo (feudal lords).

As thoroughly bound men, most samurai resented the personal freedom enjoyed by wandering ronin. Ronin were the epitome of self-determination; independent men who dictated their own path in life, answering only to themselves and making decisions as they saw fit. And like regular samurai, some ronin still wore their daisho (the pair of swords that symbolized a Samurai's status). The Forty-Seven Ronin differ from the classical estimation of the Ronin in their unwavering loyalty both to their master and to the bushido code of honor.

Historical Sources and Fictionalization

While sources do differ as to some of the details, the version given below was carefully assembled from a large range of historical sources, including some still-extant eye-witness accounts of various portions of the saga. The sequence of events and the characters in this historical narrative were presented to a wide, popular readership in the West with the 1871 publication of A.B. Mitford's Tales of Old Japan. Mitford invites his readers to construe the story of the forty-seven ronin as historically accurate; and while Mitford's tale has long been considered a standard work, some of its precise details are now questioned. Nevertheless, even with plausible defects, Mitford's work remains a conventional starting point for further study. Whether as a mere literary device or as a claim for ethnographic veracity, Mitford explains:

In the midst of a nest of venerable trees in Takanawa, a suburb of Yedo, is hidden Sengakuji, or the Spring-hill Temple, renowned throughout the length and breadth of the land for its cemetery, which contains the graves of the Forty-seven R├┤nins, famous in Japanese history, heroes of Japanese drama, the tale of whose deed I am about to transcribe. [emphasis added][1]

Fictionalized accounts of these events are known as Ch┼źshingura, a genre unto themselves. The story was first popularized in numerous plays including bunraku (Japanese puppet theater) and kabuki (traditional Japanese theater); because of the censorship laws of the shogunate in the Genroku era which forbade portrayal of current events, the names were changed. While the version given by the playwrights may have come to be accepted as historical fact by some, the Chushingura was written some 50 years after the fact; and numerous historical records about the actual events which pre-date the Chushingura survive.

The bakufu's censorship laws had relaxed somewhat 75 years later, when Japanologist Isaac Titsingh first recorded the story of the Forty-Seven Ronin as one of the significant events of the Genroku era.

The Story of the Forty-Seven Ronin

Background events

In 1701 (by the Western calendar), two daimyo, Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori, the young daimyo of Ak┼Ź (a small fiefdom or han in western Honsh┼ź), and Kamei Sama, another noble, were ordered to arrange a fitting reception for the envoys of the Emperor in Edo, during their sankin k┼Źtai service to the Shogun.[1]

These daimyo names are not fiction, nor is there any question that something actually happened on the fourteenth day of the third month of the fourteenth year of Genroku, as time was reckoned in 1701 Japan. What is commonly called the Ak┼Ź incident was an actual event.[2]

Asano and Kamei were to be given instruction in the necessary court etiquette by Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a high ranking Edo official in the hierarchy of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi's shogunate. He became upset at them, allegedly because of either the small presents they offered him (in the time-honored compensation for such an instructor), or because they would not offer bribes as he wanted. Other sources say that he was a naturally rude and arrogant individual, or that he was corrupt, which offended Asano, a rigidly moral Confucian. Regardless of the reason, whether Kira treated them poorly, insulted them or failed to prepare them for fulfilling specific ceremonial duties,[1] offense was taken.[2]

While Asano bore all this stoically, Kamei Sama became enraged, and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, the quick thinking counselors of Kamei Sama averted disaster for their lord and clan (for all would have been punished if Kamei Sama killed Kira) by quietly giving Kira a large bribe; Kira thereupon began to treat Kamei Sama very nicely, which calmed Kamei's anger.[1]

However, Kira continued to treat Asano harshly, because he was upset that the latter had not emulated his companion; Kira taunted and humiliated him in public. Finally, Kira insulted Asano as a country boor with no manners, and Asano could restrain himself no longer. He lost his temper, and attacked Kira with a dagger, but only wounded him in the face with his first strike; his second missed and hit a pillar. Guards then quickly separated them.[1]

Kira's wound was hardly serious, but the attack on a shogunate official within the boundaries of the Shogun's residence, was considered to be a grave offense. Any kind of violence, even drawing a sword, was completely forbidden in Edo castle.[1] Therefore Asano was ordered to commit seppuku. Asano's goods and lands were to be confiscated after his death, his family was to be ruined, and his retainers were to be made ronin. The daimyo of Ak┼Ź had removed his sword from its scabbard within Edo Castle, and for that offense, the daimyo was ordered to kill himself.[2]

This news was carried to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano's principal Samurai and counsellor, who took command and moved the Asano family away, before complying with bakufu orders to surrender the castle to the agents of the government.

The ronin plot revenge

Of Asano's over three hundred men, at least forty-seven, especially their leader Ōishi, refused to let their lord go unavenged. Some sources say Oishi and as many as 59 other ronin decided that the time had come to move against Kira, but Oishi would allow only 46 of the men to participate with him in the attempt, sending the other 13 back home to their families.

Even though revenge was prohibited, they banded together, swearing a secret oath to avenge their master by killing Kira, even though they knew they would be severely punished for doing so. However, Kira was well guarded, and his residence had been fortified to prevent just such an event. They saw that they would have to put him off his guard before they could succeed. To quell the suspicions of Kira and other shogunate authorities, they dispersed and became tradesmen or monks.

Ōishi himself took up residence in Kyoto, and begun to frequent brothels and taverns, as if nothing were further from his mind than revenge. Kira still feared a trap, and sent spies to watch the former retainers of Asano.

One day, as ┼îishi returned drunk from some haunt, he fell down in the street and went to sleep, and all the passers-by laughed at him. A Satsuma man, passing by, was infuriated by this behavior on the part of a samuraiÔÇôboth by his lack of courage to avenge his master, as well as his current debauched behavior. The Satsuma man abused and insulted him, and kicked him in the face (to even touch the face of a samurai was a great insult, let alone strike it), and spat on him.

Not too long after, Ōishi's loyal wife of twenty years went to him and complained that he seemed to be taking his act too far. He divorced her on the spot, and sent her away with their two younger children; the oldest, a boy named Chikara, remained with his father. In his wife's place, the father bought a young pretty concubine. Kira's agents reported all this to Kira, who became convinced that he was safe from the retainers of Asano, who must all be bad samurai indeed, without the courage to avenge their master, and were harmless; he then relaxed his guard.

The rest of the faithful retainers now gathered in Edo, and in their roles as workmen and merchants, gained access to Kira's house, becoming familiar with the layout, and the character of all within. One of the retainers (Kinemon Kanehide Okano) went so far as to marry the daughter of the builder of the house, to obtain plans. All of this was reported to Ōishi. Others gathered arms and secretly transported them to Edo, another offense.

The attack

In 1702, when Ōishi was convinced that Kira was thoroughly off his guard,[1] and everything was ready, he fled from Kyoto, avoiding the spies who were watching him, and the entire band gathered at a secret meeting-place in Edo, and renewed their oaths.

Early in the morning of December 14, in a driving wind during a heavy fall of snow, Ōishi and the ronin attacked Kira Yoshinaka's mansion in Edo. According to a carefully laid-out plan, they split up into two groups and attacked, armed with swords and bows. One group, led by Ōishi, was to attack the front gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, was to attack the house via the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal that Kira was dead.[1]

Once Kira was dead, they planned to cut off his head, and lay it as an offering on their master's tomb. They would then turn themselves in, and wait for their expected sentence of death. All this had been confirmed at a final dinner, where Ōishi had asked them to be careful, and spare women, children, and other helpless people.

Ōishi had four men scale the fence and enter the porter's lodge, capturing and tying up the guard there. He then sent messengers to all the neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but retainers out to avenge the death of their master, and no harm would come to anyone else; they were all perfectly safe. The neighbors, who all hated Kira, did nothing.

After posting archers (some on the roof), to prevent those in the house (who had not yet woken up) from sending for help, Ōishi sounded the drum to start the attack. Ten of Kira's retainers held off the party attacking the house from the front, but Ōishi Chikara's party broke into the back of the house.

Kira, in terror, took refuge in a closet in the verandah, along with his wife and female servants. The rest of his retainers, who slept in a barracks outside, attempted to come into the house to his rescue. After overcoming the defenders at the front of the house, the two parties of father and son joined up, and fought with the retainers who came in. The latter, perceiving that they were losing, tried to send for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers posted to prevent that.

Eventually, after a fierce struggle, the last of Kira's retainers was subdued; in the process they killed sixteen of Kira's men and wounded twenty-two, including his grandson. Of Kira, however, there was no sign. They searched the house, but all they found were crying women and children. They began to despair, but Ōishi checked Kira's bed, and it was still warm, so he knew he could not be far.[1]

The death of Kira

A renewed search disclosed an entrance to a secret courtyard hidden behind a large scroll; the courtyard held a small building for storing charcoal and firewood, where two more hidden armed retainers were overcome and killed. A search of the building disclosed a man hiding; he attacked the searcher with a dagger, but the man was easily disarmed. He refused to say who he was, but the searchers felt sure it was Kira, and sounded the whistle. The ronin gathered, and Ōishi, with a lantern, saw that it was indeed Kira. As a final proof, his head bore the scar from Asano's attack.

At that, Ōishi went on his knees, and in consideration of Kira's high rank, respectfully addressed him, telling him they were retainers of Asano, come to avenge him as true samurai should, and inviting Kira to die as a true samurai should, by killing himself. Ōishi indicated he personally would act as a second, and offered him the same dagger that Asano had used to kill himself.[1]

However, no matter how much they entreated him, Kira crouched, speechless and trembling. At last, seeing it was useless to ask, Ōishi ordered the ronin to pin him down, and killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger. Kira was killed on the night of the fourteenth day of the twelfth month of the fifteenth year of Genroku.

They then extinguished all the lamps and fires in the house (lest any cause the house to catch fire, and start a general fire that would harm the neighbors), and left, taking the head.[1]

One of the ronin, the ashigaru Terasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to travel to Ak┼Ź and inform them that their revenge had been completed. Though Kichiemon's role as a messenger is the most widely-accepted version of the story, other accounts have him running away before or after the battle, or being ordered to leave before the ronin turn themselves in. [3]

The aftermath

As day was now breaking, they quickly carried Kira's head to their lord's grave in Sengaku-ji, causing a great stir on the way. The story quickly went around as to what had happened, and everyone on their path praised them, and offered them refreshment.[1]

On arriving at the temple, the remaining forty-six ronin washed and cleaned Kira's head in a well, and laid it, and the fateful dagger, before Asano's tomb. They then offered prayers at the temple, and gave the abbot of the temple all the money they had left, asking him to bury them decently, and offer prayers for them. They then turned themselves in; the group was broken into four parts and put under guard of four different daimyos.

During this time, two friends of Kira came to collect his head for burial; the temple still has the original receipt for the head, which the friends and the priests who dealt with them all signed.

The shogunate officials were in a quandary. The samurai had followed the precepts of bushido by avenging the death of their lord; but they also defied shogunate authority by exacting revenge which had been prohibited. In addition, the Shogun received a number of petitions from the admiring populace on behalf of the ronin. As expected, the ronin were sentenced to death; but the Shogun had finally resolved the quandary by ordering them to honorably commit seppuku, instead of having them executed as criminals.[1] Each of the assailants killed himself in the ritualistic fashion.[2]

The forty-six ronin did so on February 4, 1703. (This has caused a considerable amount of confusion ever since, with some people referring to the "forty-six ronin"; this refers to the group put to death by the Shogun, the actual attack party numbered forty-seven.) They were also buried in Sengaku-ji, as they had requested, in front of the tomb of their master.[1] The forty-seventh ronin eventually returned from his mission, and was pardoned by the Shogun (some say on account of his youth). He lived until the age of 78, and was then buried with his comrades. The assailants who died by seppuku were subsequently interred on the grounds of Sengaku-ji.[2]

The clothes and arms they wore are still preserved in the temple to this day, along with the drum and whistle; the armor was all home-made, as they had not wanted to possibly arouse suspicion by purchasing any.

The tombs became a place of great veneration, and people flocked there to pray. The graves at this temple have been visited by a great many people throughout the years since the Genroku era.[2] One of those who came was a Satsuma man, the same one who had mocked and spat on Ōishi as he lay drunk in the street. Addressing the grave, he begged for forgiveness for his actions, and for thinking that Ōishi was not a true samurai. He then committed suicide, and is buried next to the graves of the ronin.[1]

Analysis And Critical Significance

It has been said of the Ch├╗shingura tale that if you study it long enough, you will understand everything about the Japanese. The theory is that all of the values espoused in the tale are quintessentially and culturally Japanese, and the tale is a distillation of the character of the Japanese people.

Even in the present day, many years after the events and their fictionalization, hundreds of books about the Forty-Seven Ronin are on store shelves, from histories to historical fiction to cultural analysis of the Ch├╗shingura tales. Initially referring to the Kanadehon Ch├╗shingura of 1748, "Ch├╗shingura" is now an all-encompassing term for the entire body of cultural production that ultimately stems from the Ak├┤ Incident of 1701-1703.

The story's durability in later imagination lies less in the drama implicit in its outline than in the ambiguity of motivation for the initial palace incident. The historical record, for example, does not explain why Asano attacked Kira in the first place. The fact that the ronin in their voluminous correspondence never touched on the reason for Asano's grudge suggests that even they did not really know.

Even greater ambiguity lies in the motivation and action of the ronin. The Forty-Seven Ronin called their actions a vendetta, but their actions did not fit with the legal or conventional definition of a vendetta at the time, since Kira had not murdered their master, but had nearly been murdered by him. There was no legal or moral justification for avenging the death of one's lord, only that of a family member. The Ronin actually called on a Confucian scholar to help justify their action. The nature and spirit of the act is also in question: was it an act of loyalty to their master, a protest of the bakufu's leniency towards Kira, or a matter of honor in finishing what their master had started? Or, as one school of interpretation would have it, were they impoverished samurai desperate for a new job and trying to prove their credentials?

The myriad possibilities surrounding the event pave the way for myriad interpretations and adaptations, encouraging the survival of the endlessly told Ch├╗shingura to the modern times. Ch├╗shingura was the only one of the "Three Great Vendettas" of the Edo period that did in fact survive the war: nothing more was to be seen of the Soga Brothers or Araki Bunzaemon, names that are today virtually unknown to the majority of Japanese. Ch├╗shingura owes its survival to the many ambiguities explored above.

It has survived and been reinvented again and again, with many of its re-tellings and adaptations were, in one way or another, reflections of the values and ideologies of their times.

Ulterior motives

Though the actions of the Forty-Seven Ronin are often viewed as an act of loyalty, there was a second goal, to re-establish the Asanos' lordship and thus find a place for fellow samurai to serve. Hundreds of samurai who had served under Asano had been left jobless and many were unable to find employment as they had served under a disgraced family. Many lived as farmers or did simple handicrafts to make ends meet. The Forty-Seven Ronin's act cleared their names and many of the unemployed samurai found jobs soon after the ronin had been sentenced to an honorable end. Asano Daigaku Nagahiro, Takuminokami's younger brother and heir was allowed by the Tokugawa Shogunate to re-establish his name, though his territory was reduced to a tenth of the original.

Criticism (within Bushido)

The ronin spent a year waiting for the "right time" for their revenge. It was Yamamoto Tsunetomo, author of the Hagakure, who asked this famous question: "What if, nine months after Asano's death, Kira had died of an illness?" To which the answer obviously is: then the forty-seven ronin would have lost their only chance at avenging their master. Even if they had claimed, then, that their dissipated behavior was just an act, that in just a little more time they would have been ready for revenge, who would have believed them? They would have been forever remembered as cowards and drunkardsÔÇöbringing eternal shame to the name of the Asano clan.

The right thing for the ronin to do, wrote Yamamoto, according to proper bushido, was to attack Kira and his men immediately after Asano's death. The ronin would probably have suffered defeat, as Kira was ready for an attack at that timeÔÇöbut this was unimportant. ┼îishi was too obsessed with success. His convoluted plan was conceived in order to make absolutely certain that they would succeed at killing Kira, which is not a proper concern in a samurai: the important thing was not the death of Kira, but for the former samurai of Asano to show outstanding courage and determination in an all-out attack against the Kira house, thus winning everlasting honor for their dead master. Even if they failed at killing Kira, even if they all perished, it would not have mattered, as victory and defeat have no importance in bushido. By waiting a year they improved their chances of success but risked dishonoring the name of their clan, which is seen as the worst sin a samurai can commit. This is why Yamamoto Tsunetomo and many others claim that the tale of the forty-seven ronin is a good story of revengeÔÇöbut by no means a story of bushido.

Criticism of revenge

Immediately following the event, there were mixed feelings among the intelligentsia about whether such vengeance had been appropriate. Many agreed that, given their master's last wishes, the forty-seven had done the right thing, but were undecided about whether such a vengeful wish was proper. Over time, however, the story became a symbol, not of bushido but of loyalty to one's master and later, of loyalty to the emperor. Once this happened, it flourished as a subject of drama, storytelling, and visual art.

The Forty-Seven Ronin in the Arts

The tragedy of the Forty-seven Ronin has been one of the most popular themes in Japanese art, and has even begun to make its way into Western art. The following is nowhere near an exhaustive list of all the adaptations of the tale of the Forty-Seven Ronin, which has been adapted countless times into nearly every medium in existence, inside and outside of Japan. It only touches on some notable examples.

Plays

The incident immediately inspired a succession of kabuki and bunraku plays. The first, The Night Attack at Dawn by the Soga appeared only two weeks after they died. It was shut down by the authorities, but many others soon followed, initially especially in Osaka and Kyoto, further away from the capital. Some even took it as far as Manila, to spread the story to the rest of Asia.

The most successful of them was a bunraku puppet play called Kanadehon Chushingura (now simply called Chushingura, or "Treasury of Loyal Retainers"), written in 1748 by Takeda Izumo and two associates; it was later adapted into a kabuki play, which is still one of Japan's most popular.

In the play, to avoid the attention of the censors, the events are transferred into the distant past, to the fourteenth century reign of shogun Ashikaga Takauji. Asano became "Enya Hangan Takasada," Kira became "Ko no Moronao" and Ōishi rather transparently became "Ōboshi Yuranosuke Yoshio"; the names of the rest of the ronin were disguised to varying degrees. The play contains a number of plot twists which do not reflect the real story: Moronao tries to seduce Enya's wife, and one of the ronin dies before the attack because of a conflict between family and warrior loyalty (another possible cause of the confusion between forty-six and forty-seven).

Cinema

The play has been made into a movie at least six times in Japan. In fact, the late Meiji period marked the beginning of the Ch├╗shingura as an entirely new genre of film, which by the time it had run its course in the mid-1960s would have brought the story of the Forty-Seven Ronin to far more Japanese than ever in the past, and with a new level of power and immediacy. The film historian Misono Ky├┤hei counted a total of sixty Ch├╗shingura films in late Meiji and Taisho (1907-1926), an average of three per year. The number would rapidly multiply in the years that followed.

Earliest film adaptation

The earliest film starred Onoe Matsunosuke and was produced sometime between 1910 and 1917. It has been aired on the Jidaigeki Senmon Channel in Japan with accompanying benshi narration.

1941 film adaptation

In 1941 the Japanese military commissioned director Kenji Mizoguchi (Ugetsu) to make The 47 Ronin. They wanted a ferocious morale booster based upon the familiar rekishi geki ("historical drama") of The Loyal 47 Ronin. Instead, Mizoguchi chose for his source Mayama Chusingura, a cerebral play dealing with the story. The 47 Ronin was a commercial failure, having been released in Japan one week before the Attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese military and most audiences found the first part to be too serious, but the studio and Mizoguchi both regarded it as so important that Part Two was put into production, despite Part One's lukewarm reception. Renowned by postwar scholars lucky to have seen it in Japan, The 47 Ronin was not shown in America until the 1970s. Contemporary reviewers of this film consider it a masterpiece.

1962 film adaptation

The 1962 version Ch┼źshingurais most familiar to Western audiences, where Toshiro Mifune appears in a supporting role.

1994 film adaptation

Legendary Japanese director Kon Ichikawa directed another version in 1994.

In Hirokazu Koreeda's 2006 film Hana yori mo naho, the event of the Forty-Seven Ronin was used as a backdrop in the story, where one of the ronin is presented as being a neighbor of the protagonists.

Television

Many Japanese television shows, including single programs, short series, single seasons, and even year-long series such as the 52-part 1971 television series Daichushingura starring Mifune in the role of ┼îishi, and the more recent NHK Taiga drama Genroku Ry┼Źran, recount the events of the Forty-seven Ronin. Among both films and television programs, some are quite faithful to the Chushingura while others incorporate unrelated material or they alter some details. In addition, gaiden dramatize events and characters not originally depicted in the Chushingura.

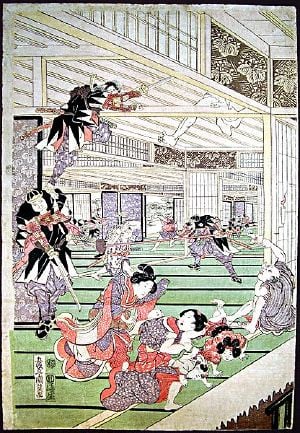

Woodblock prints

The Forty-seven Ronin are one of the most popular themes in woodblock prints, known as ukiyo-e. One book that lists subjects depicted in woodblock prints devotes no less than seven chapters to the history of the appearance of this theme in woodblocks.

Among the artists who produced prints on this subject are Utamaro, Toyokuni, Hokusai, Kunisada, and Hiroshige. However, probably the most famous woodblocks in the genre are those of Kuniyoshi, who produced at least eleven separate complete series on this subject, along with more than 20 triptychs.

In the West

The earliest known account of the Ak┼Ź incident in the West was published in 1822 in Isaac Titsingh's posthumous book, Illustrations of Japan.[2]

A widely popularized retelling of Ch┼źshingura appeared in 1871 in A. B. Mitford's Tales of Old Japan; and appended to that narrative are translations of Sengakuji documents which were presented as "proofs" authenticating the factual basis of the story. The three documents offered as proof of the tale of these Forty-Seven Ronin were:

- "the receipt given by the retainers of K├┤tsuk├ę no Suk├ę's son in return for the head of their lord's father, which the priests restored to the family,"

- "a document explanatory of their conduct, a copy of which was found on the person of each of the forty-seven men," dated in the fifteenth year of Genrolku, twelfth month, and

- "a paper which the Forty-seven Răĺnins laid upon the tomb of their master, together with the head of Kira K├┤tsuk├ę no Suk├ę."[1]

Jorge Luis Borges retold the story in his first short story collection, A Universal History of Infamy, under the title "The Uncivil Teacher of Etiquette, Kotsuke no Suke."

The story of the Forty-seven Ronin makes an appearance in many modern works, most notably in John Frankenheimer's 1998 film Ronin. More recently, in 2013 it was made into a 3D period fantasy action-adventure film, titled 47 Ronin, starring Keanu Reeves and Hiroyuki Sanada. Last Knights is a 2015 action drama film, based on the legend of the Forty-Seven Ronin, starring Clive Owen and Morgan Freeman in the lead roles.

Notes

- ÔćĹ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 A.B. Mitford, Tales of Old Japan (Dover Publications, 2005, ISBN 0486440621).

- ÔćĹ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Isaac Titsingh, Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns (Routledge, 2009, ISBN 0415546710).

- ÔćĹ Henry D. Smith II, The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh R┼Źnin and the Ch┼źshingura Imagination Japan Review 16 (2004): 3-65.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allyn, John. The Forty-Seven Ronin Story. C.E. Tuttle Co, 1989. ISBN 0804801967

- Izumo, Takeda; Chushingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers): A Puppet Play. Columbia University Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0231035316

- Mitford, A.B. Tales of Old Japan. Dover Publications, 2005. ISBN 0486440621

- Robinson, B.W. Kuniyoshi: The Warrior Prints. Oxford: Phaidon, 1982. ISBN 0714822272

- Sato, Hiroaki. Legends of the Samurai. Harry N. Abrams, 2012. ISBN 1590207300

- Steward, Basil. Subjects Portrayed in Japanese Color Prints. Albert Saifer, 1973. ISBN 0875567525

- Titsingh, Isaac. Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0415546710

- Weinberg, David R. Kuniyoshi: The Faithful Samurai. KIT Publishers, 2006. ISBN 9074822851

External links

All links retrieved April 1, 2024.

- The Tale of the 47 Ronin ThoughtCo.

- The Tale of the 47 Ronin Ronin Gallery.

- Sengakuji Temple - Site of the 47 ronin's graveyard Japan Guide.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.