This article is about the Roman philosopher. For the Native American tribe, see the article entitled Seneca nation.

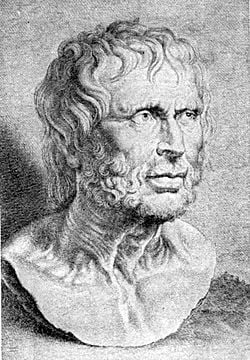

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (often known simply as Seneca, or Seneca the Younger) (c. 4 B.C.E.‚Äď 65 C.E.) was a Roman philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and writer of the Silver Age of Latin literature. During the times when he was not involved in Roman politics, he wrote nine tragedies, a satire, philosophical essays, a treatise on meteorology, and 124 letters dealing with moral issues. He was the earliest Stoic writer whose original works survived intact, instead of as fragments imbedded in the works of later writers. A Middle Stoic and eclectic, Seneca did not contribute many new ideas or concepts but wrote clearly and brilliantly about ethics, moral education, psychology and natural philosophy. For eight years he served as an advisor to the Emperor Nero, and attempted to guide his government according to Stoic ideals.

The early Christian church believed that he had known Saint Paul and therefore granted his works legitimacy and preserved them. Seneca‚Äôs works were read by Medieval scholars and his tragedies‚ÄĒwith their gloominess, ghosts, and witches‚ÄĒhad a powerful influence on Elizabethan drama.

Life

Born in Córdoba, Spain in 4 B.C.E., Seneca was the second of three sons of Helvia and Marcus (Lucius) Annaeus Seneca, a wealthy rhetorician known as Seneca the Elder. Seneca's older brother, Gallio, became proconsul at Achaea (where he encountered the apostle Paul about 52 C.E.), and Seneca was uncle to the poet Lucan, by his younger brother, Annaeus Mela.

Tradition relates that he was a sickly child, and that he was taken to Rome by his aunt, who was married to the prefect Gaius Galerius, to be educated in the school of the Sextii. He was trained in rhetoric, and was introduced to Stoic philosophy by Attalos and Sotion. Later he also studied neo-Pythagoreanism. In 25 C.E. Seneca followed his aunt to Egypt for treatment for an illness.

In 31 C.E. he returned to Rome and became a successful advocate. He came into conflict with the Emperor Caligula who nearly had him executed around 37 B.C.E.; he was only spared because Caligula did not believe Seneca’s poor health would allow him to live for long. In 41 C.E. Messalina, the wife of the Emperor Claudius, persuaded Claudius to exile Seneca to Corsica, accusing him of adultery with Julia Livilla, the daughter of Claudius' brother Germanicus. In Corsica Seneca devoted time to the study of philosophy and natural science, and wrote the three Consolationes.

In 49 C.E., Claudius’s new wife, Agrippina the Younger, had Seneca recalled to Rome to tutor her son, L. Domitius, who was to become the Emperor Nero. In 50 C.E. Seneca married a wealthy and influential woman, Pompeia Paulina, and became praetor. When Claudius died in 54 C.E., Agrippina secured the recognition of Nero as emperor over Claudius' son, Britannicus. Seneca became Nero’s closest advisor, along with his friend and the praetorian prefect, Sextus Afranius Burrus. Nero’s first speech was drafted by Seneca and promised liberty to the Senate. For the first five years, the quinquennium Neronis, Nero ruled wisely under the influence of Seneca and Burrus. They instituted financial and judicial reforms, and advocated more humane treatment of slaves. Their protégé Corbulo defeated the Parthians, and a new administration followed the suppression of Boudicca’s rebellion in Britain. Nero became more and more tyrannical, and as his wife Poppaea gained more influence, Seneca's enemies gradually turned Nero against him. After Burrus died in 62 C.E., Seneca asked to retire from public life, and devoted more time to study and writing.

In 65 C.E., Seneca was accused of being involved in a plot to murder Nero, the Pisonian conspiracy. Without a trial, Seneca was ordered by Nero to commit suicide. Tacitus gives an account of the suicide of Seneca, portraying him as meeting death with calm and fortitude. His wife, Pompeia Paulina, who intended to commit suicide after Seneca's death, was sentenced to live by Nero.

Works

The works attributed to Seneca include a satire, an essay on meteorology, philosophical essays, 124 letters dealing with moral issues, and nine tragedies. One of the tragedies attributed to him, Octavia, is now known not to be of his authorship, and another, Hercules on Oeta, is under question.

The Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii is a political satire on the deification of Claudius.

Philosophical Works

The seven books of Naturales Quaestiones deal with natural science and reflect the works of Posidonius. The rest of Seneca’s philosophical works are concerned mostly with ethics and morality. The three Consolationes, written during his exile in Corsica, Ad Marciam, Ad Helviam matrem, and Ad Polybium, discuss the meaning of life and the proper attitude towards death and loss. They were intended to console two parents for the deaths of their sons, and his own mother for his absence in exile. During the same period he wrote De Ira, a treatise on the consequences of anger and how it can be controlled. In the year that he was recalled to Rome, he wrote De brevitate vitae, explaining that even a short lifetime is long enough if the time is used correctly. In 56 C.E., he addressed De clementia to Nero, pointing out that mercy is a supreme virtue in an emperor. The Epistula morales, 124 essays dedicated to Lucilus Junior, discuss a number of moral issues and are said to be among his best philosophical writing. De tranquillitate animi, De constantia sapientis, De vita beata, and De otio discuss the Stoic way of life and the attributes of a wise man. The seven books of De beneficiis examine the benefits of both giving and receiving. The ideas expressed by Seneca reflected the standard teachings of Middle Stoicism, but were articulated in such a way as to make them appealing and easily understandable.

Tragedies

Seneca is best known for his tragedies, which are the only surviving examples of Latin tragic drama. There is no evidence that the plays were ever performed on stage; they were written while Seneca was in exile and are very different from the type of drama that was popular at the time. They were widely read in medieval universities and had a powerful influence on European drama of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. A translation of the tragedies was published in England in 1581. Elements of Seneca’s dramatic style can be found in the plays of that time period, including the atmosphere of gloom and horror, long soliloquies, rhetorical choruses, stoicism, the theme of revenge, the inclusion of the supernatural, and characters like cruel tyrants, witches, madmen and innocents. Seneca’s tragedies have been successfully staged during modern times.

Seneca and St. Paul

Seneca’s older brother Gallio was said to have met the disciple Paul in Achaea in 52 C.E., and a series of letters, Cujus etiam ad Paulum apostolum leguntur epistolae, were said to be correspondence between Seneca and Saint Paul. (These letters were revered by early Christian authorities but most scholars do not believe they are authentic.) Some medieval writers believed that Seneca had been converted to Christianity by Paul. Seneca’s works were preserved by the early Christians, and studied by Augustine of Hippo, Jerome and Boethius. His works were included in medieval anthologies, and Dante, Petrarch and Geoffrey Chaucer all make references to them. In 1614 Erasmus edited the first English translation of Seneca’s essays on morality. Seneca’s writings influenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Calvin, and Michel de Montaigne.

Dialogues

Note: dates are approximate.

- (40 C.E.) Ad Marciam, De consolatione (‚ÄúTo Marcia, On consolation‚ÄĚ)

- (41 C.E.) De Ira (‚ÄúOn anger‚ÄĚ)

- (42 C.E.) Ad Helviam matrem, De consolatione (‚ÄúTo Helvia, On consolation‚ÄĚ)

- (44 C.E.) De Consolatione ad Polybium (‚ÄúTo Polybius, On consolation‚ÄĚ)

- (49 C.E.) De Brevitate Vitae (‚ÄúOn the shortness of life‚ÄĚ)

- (62 C.E.) De Otio (‚ÄúOn leisure‚ÄĚ)

- (63 C.E.) De Tranquillitate Animi (‚ÄúOn tranquillity of mind‚ÄĚ)

- (64 C.E.) De Providentia (‚ÄúOn providence‚ÄĚ)

- (??) De Constantia Sapientiis (‚ÄúOn the Firmness of the Wise Person‚ÄĚ)

- (??) De Vita Beata (‚ÄúOn the happy life‚ÄĚ)

Tragedies

- Hercules Furens (‚ÄúThe Madness of Hercules‚ÄĚ)

- Troades (‚ÄúThe Trojan Women‚ÄĚ)

- Medea

- Phoenissae (‚ÄúThe Phoenician Women‚ÄĚ)

- Phaedra

- Agamemnon

- Thyestes

- Oedipus

- Hercules Oetaeus (‚ÄúHercules on Oeta‚ÄĚ): Problematic authorship

- Octavia : Problematic authorship

Other

- (54 C.E. ) Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii] (‚ÄúThe Pumpkinification of the Divine Claudius‚ÄĚ)

- (56 C.E. ) De Clementia (‚ÄúOn Clemency‚ÄĚ)

- (63 C.E.) De Beneficiis (‚ÄúOn Benefits‚ÄĚ) [seven books]

- (63 C.E.) Naturales quaestiones [seven books]

- (64 C.E.) Epistulae morales ad Lucilium

Quotations

- A gem cannot be polished without friction, nor a man perfected without trials.

- A man who suffers before it is necessary, suffers more than is necessary.

- A physician is not angry at the intemperance of a mad patient, nor does he take it ill to be railed at by a man in fever. Just so should a wise man treat all mankind, as a physician does his patient, and look upon them only as sick and extravagant.

- A quarrel is quickly settled when deserted by one party; there is no battle unless there be two.

- A well governed appetite is the greater part of liberty.

- All art is but imitation of nature.

- All cruelty springs from weakness.

- Anger is like those ruins which smash themselves on what they fall.

- Anger, if not restrained, is frequently more hurtful to us than the injury that provokes it.

- Anger: an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.

- The deferring of anger is the best antidote to anger.

- Consider, when you are enraged at any one, what you would probably think if he should die during the dispute.

- As is a tale, so is life: not how long it is, but how good it is, is what matters.

- As long as you live, keep learning how to live.

- Be wary of the man who urges an action in which he himself incurs no risk.

- Behold a worthy sight, to which the God, turning his attention to his own work, may direct his gaze. Behold an equal thing, worthy of a God, a brave man matched in conflict with evil fortune.

- Brave men rejoice in adversity, just as brave soldiers triumph in war.

- Consult your friend on all things, especially on those which respect yourself. His counsel may then be useful where your own self-love might impair your judgment.

- Conversation has a kind of charm about it, an insinuating and insidious something that elicits secrets from us just like love or liquor.

- Crime when it succeeds is called virtue.

- Death is the wish of some, the relief of many, and the end of all.

- Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labor does the body.

- Do not ask for what you will wish you had not got.

- Every reign must submit to a greater reign.

- Every sin is the result of a collaboration.

- Expecting is the greatest impediment to living. In anticipation of tomorrow, it loses today.

- God is the universal substance in existing things. He comprises all things. He is the fountain of all being. In Him exists everything that is.

- He has committed the crime who profits by it.

- He who does not prevent a crime when he can, encourages it.

- He that does good to another does good also to himself.

- He who dreads hostility too much is unfit to rule.

- He who has great power should use it lightly.

- I don't trust liberals, I trust conservatives.

- I will govern my life and thoughts as if the whole world were to see the one and read the other, for what does it signify to make anything a secret to my neighbor, when to God, who is the searcher of our hearts, all our privacies are open?

- If a man knows not what harbor he seeks, any wind is the right wind. If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable.

- If you wished to be loved, love.

- Ignorant people see life as either existence or non-existence, but wise men see it beyond both existence and non-existence to something that transcends them both; this is an observation of the Middle Way.

- It is a rough road that leads to the heights of greatness.

- It is another's fault if he be ungrateful, but it is mine if I do not give. To find one thankful man, I will oblige a great many that are not so.

- It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare, it is because we do not dare that they are difficult.

- It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor.

- It is quality rather than quantity that matters.

- It is the sign of a great mind to dislike greatness, and to prefer things in measure to things in excess.

- Light troubles speak; the weighty are struck dumb.

- Modesty forbids what the law does not.

- Most powerful is he who has himself in his own power.

- No one can be happy who has been thrust outside the pale of truth. And there are two ways that one can be removed from this realm: by lying, or by being lied to.

- No one is laughable who laughs at himself.

- One crime has to be concealed by another.

- Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful.

- Shall I tell you what the real evil is? To cringe to the things that are called evils, to surrender to them our freedom, in defiance of which we ought to face any suffering.

- So live with men as if God saw you and speak to God, as if men heard you.

- Success is not greedy, as people think, but insignificant. That is why it satisfies nobody.

- That grief is light which can take counsel.

- The bad fortune of the good turns their faces up to heaven; the good fortune of the bad bows their heads down to the earth.

- The good things of prosperity are to be wished; but the good things that belong to adversity are to be admired.

- The pressure of adversity does not affect the mind of the brave man... It is more powerful than external circumstances.

- The things hardest to bear are sweetest to remember.

- There is as much greatness of mind in acknowledging a good turn, as in doing it.

- There is no delight in owning anything unshared.

- There is no person so severely punished, as those who subject themselves to the whip of their own remorse.

- There is none made so great, but he may both need the help and service, and stand in fear of the power and unkindness, even of the meanest of mortals.

- Those who boast of their descent, brag on what they owe to others.

- True happiness is... to enjoy the present, without anxious dependence upon the future.

- We are more often frightened than hurt; and we suffer more from imagination than from reality.

- We become wiser by adversity; prosperity destroys our appreciation of the right.

- We can be thankful to a friend for a few acres, or a little money; and yet for the freedom and command of the whole earth, and for the great benefits of our being, our life, health, and reason, we look upon ourselves as under no obligation.

- We should every night call ourselves to an account: what infirmity have I mastered to-day? what passions opposed? what temptation resisted? what virtue acquired? Our vices will abate of themselves if they be brought every day to the shrift.

- What difference does it make how much you have? What you do not have amounts to much more.

- Whatever one of us blames in another, each one will find in his own heart.

- When I think over what I have said, I envy dumb people.

- Wherever there is a human being, there is an opportunity for a kindness

- Wisdom does not show itself so much in precept as in life - in firmness of mind and a mastery of appetite. It teaches us to do as well as to talk; and to make our words and actions all of a color.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berry, Paul and Lucius Annaeus Seneca. Encounter Between Seneca and Christianity. Edwin Mellen Press, 2002.

- Cunnally, John. "Nero, Seneca, and the Medallist of the Roman Emperors", Art Bulletin 68:2 (June 1986): 314-317.

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. The stoic philosophy of Seneca: Essays and letters of Seneca New York: Doubleday, 1958.

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Seneca Epistles 1-65 (Seneca). John W. Basore, trans. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Seneca in English. Don Share, ed. New York: Penguin Classics / Penguin USA, 1998.

- Strem, George G. The life and teaching of Lucius Annaeus Seneca. Vantage Press; 1st ed, 1981.

External links

All links retrieved January 26, 2023.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.