The Right Honorable Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, KG, OM, CH, FRS, PC (November 30, 1874 âJanuary 24, 1965) was a British statesman, best known as prime minister of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. At various times a soldier, journalist, author, and politician, Churchill is generally regarded as one of the most important leaders in British and world history. Considered reactionary on some issues, such as granting independence to Britain's colonies and at times regarded as a self-promoter who changed political parties to further his career, it was his wartime leadership that earned him iconic status. Some of his peace-time decisions, such as restoring the Gold Standard in 1924, were disastrous as was his World War I decision to land troops on the Dardanelles. However, during 1940, when Britain alone opposed Hitler's Nazi Germany in the free world, his stirring speeches inspired, motivated, and uplifted a whole people during their darkest hour.

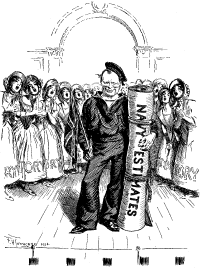

Churchill saw himself as a champion of democracy against tyranny, and was profoundly aware of his own role and destiny. Indeed, he believed that God had placed him on earth to carry out heroic deeds for the protection of Christian civilization and human progress. A providential understanding of history would concur with Churchill's self-understanding. Considered old-fashioned, even reactionary by some people today, he was actually a visionary whose dream was of a united world, beginning with a union of the English-speaking peoples, then embracing all cultures. In his youth, he cut a dashing figure as a cavalry officer as seen in the 1972 film Young Winston (directed by Richard Attenborough), but the images of him that are the most widely remembered are as a rather overweight, determined, even pugnacious looking senior statesman as he is depicted to the right.

Early life

Born at Blenheim Palace, near Woodstock, Oxfordshire, Winston Churchill was a descendant of the first famous member of the Churchill family, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Winston's politician father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was the third son of John Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough. Churchill's legal surname was Spencer-Churchill, but starting with his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, his branch of the family always used just the name Churchill in public life. Winston's mother was Lady Randolph Churchill (née Jennie Jerome), daughter of American millionaire Leonard Jerome. Neither parent showed young Winston much affection or love but he greatly admired his father and was also influenced towards politics as a result of his distinguished but short career.

Churchill spent much of his childhood at boarding schools, including the Headmaster's House at Harrow School, one of the most prestigious private schools in the United Kingdom. He famously sat the entrance exam but on confronting the Latin paper he carefully wrote the title, his name, and the number 1 followed by a dot and could not think of anything else to write. He had no interest whatsoever in the classics. Doubt has been cast on how the grandson of a Duke could be admitted to Harrow without any Latin, but certainly he was placed in the bottom division where he was primarily taught English, at which he excelled. Today at Harrow, there is an annual Churchill essay prize on a subject chosen by the head of the English department.

He was rarely visited by his mother, whom he virtually worshiped, despite his letters begging her to either come or let his father permit him to come home. He had a distant relationship with his father despite keenly following his father's career. Once, in 1886, he is reported to have proclaimed "My daddy is Chancellor of the Exchequer and one day that's what I'm going to be." His desolate, lonely childhood stayed with him throughout his life. Yet Churchill loved his father, âdemanding and unforgiving as he was,â and when his own daughter once asked him who he would most like to fill a vacant chair at dinner (this was in 1947) he replied, âOh, my father, of courseâ (Meacham 2003).

He was very close to his nurse, Elizabeth Ann Everest (nicknamed "Woom" by Churchill), and was deeply saddened when she died on July 3, 1895. Churchill paid for her gravestone at the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium.

Churchill did badly at Harrow, regularly being punished for poor work and lack of effort. His nature was independent and rebellious and he failed to achieve much academically, failing some of the same courses numerous times despite showing great ability in other areas such as math and history, in both of which he was placed at times at the top of his class. He later always regretted that university entrance had not been an option for him and described 1896 to 1897, when he was in India, as the university of his life. He read widely, including Schopenhauer, Malthus, Darwin, Aristotle (on politics), Henry Fawcett's Political Economy, William Lecky's European Morals and Rise and Influence of Rationalism, Pascal's Provincial Letters, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, Liang's Modern Science and Modern Thought, Rochefort's Memoirs, and Hallam's Constitutional History, plus one hundred volumes of the Annual Register covering the last one hundred years of parliamentary debates (in the UK) (Muller 2009).

The view of Churchill as a failure at school is one that he himself propagated, probably due to his father's intense dislike of the young Winston and his obvious readiness to label his son a disappointment. He did, however, become the school's fencing champion. He almost certainly protested too loudly about his academic abilities, but this was part of the sometimes self-deprecating, sometimes egotistical literary style he made his own.

Young Churchill

After Harrow he went to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. He already had political ambition but knew that in order to stand a chance in politics he needed money and a reputation. The military, with the possibility of distinguishing himself in action, would provide the second, while journalism and writing would provide the first. He appears to have had an uncanny prescience of his own future role and destiny. In a conversation that took place in 1891 while still at Harrow with his contemporary Sir Murland Evans about their ambitions, Churchill (then 16) remarked âI can see vast changes coming over a now peaceful world; great upheavals, terrible struggles, wars such as one cannot imagineâŠ. London will be attacked and I will be very prominent in the defense of Londonâ (Gilbert 1997: 215). Few in 1891 would think an attack on London a remote possibility and for Churchill to have foreseen his future role in the defense of Britain is truly remarkable. He enjoyed Sandhurst, made more friends there than he had at school and graduated eighth out of 150, an achievement of which his deceased father would have been proud. He spent his last three years at Harrow in the Army class. Churchill himself wrote, âI passed out eighth in my batch of a hundred and fifty. I mention this because it shows that I could learn quickly enough the things that matteredâ (1996: 59). Churchill joined the Fourth Hussars in 1895 and saw action on the Indian northwest frontier and in the Sudan where he took part in the Battle of Omdurman (1898). He chose cavalry, qualifying for a cadetship because he loved horses and there was actually less competition to join, since it cost more than the infantry (Churchill 1996: 35). He commented that once he had become a gentlemen cadet, he âacquired a new status in his father's eyesâ (Churchill 1996: 45). However, when he suggested that he might assist him as his private secretary, he âfroze me [Winston] into stoneâ (Churchill 1996: 46).

Churchill volunteered for service in places where action was likely, not because he wanted to place himself at risk, but to further his personal agenda and to quench his thirst for adventure (Churchill 1996: 80). In 1895, he went to Cuba while on leave as a military observer during the Spanish-Cuban war at the invitation of the Spanish government, who awarded him the Cruz Rosa (Red Cross) medal. While there, he soon acquired a taste for Havana cigars, which he would smoke for the rest of his life. He also paid his first visit to the U.S., where he stayed at the home of William Bourke Cockran, an admirer of his mother. Cockran was an established American politician, and a member of the House of Representatives. He greatly influenced Churchill, both in his approach to oratory and politics, and encouraging a love of America (Jenkins 2002). Next he served in India, where he hoped that there might be a âmutiny or a revoltâ to deal with (Churchill 1996: 44). There, he saw action against the Pathans on the North West Frontier. In 1898, he joined the 21st Lancers and fought at Omdurman in Sudan under Kitchener in what has been described as the last cavalry charge. He reported this for the Morning Post.

While in the army, Churchill supplied military reports for the Daily Graphic, the Pioneer, and the Daily Telegraph, starting from Cuba and wrote books such as The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898) and The River War (1899). After leaving the British Army in 1899, Churchill worked as a war correspondent for the Morning Post. While reporting the Boer War in South Africa, he was taken prisoner by the Boers, but made headline news when he escaped. On returning to England he wrote about his experiences in the book, London to Ladysmith (1900). He became something of a national hero, which was just what he wanted to achieve in order to seek nomination as a prospective parliamentary candidate, or, as he put it, âforge his sword into a despatch box.â One of his main ambitions was to achieve something significant while still young and he despaired that leadership was always in the hands of old men. Ironically, he was an old man when he achieved his highest office.

Ministerial office

Churchill was elected to Parliament as the Conservative member for Oldham in 1900. By 1904, he found himself out of sympathy with his party on two main issues, that of social reform and of free trade. He supported both while the Conservatives were reluctant to introduce legislative change aimed at fighting poverty and were protectionist on the issue of free trade. Controversially, he crossed the floor to the Liberals. In 1906, Churchill won Manchester North West as a liberal. In the Liberal government of Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1863 â 1908) he served as under-secretary of state for the Colonies and soon became the most prominent member of the government outside the Cabinet. When Campbell-Bannerman was succeeded by Herbert Henry Asquith (1864 â 1945) in 1908, it came as little surprise when Churchill was promoted to the Cabinet as president of the Board of Trade. Under the law at the time, a newly appointed Cabinet minister was obliged to seek re-election at a by-election. Churchill lost his Manchester seat to the Conservative William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford, but was soon elected in another by-election at Dundee. As president of the Board of Trade, he pursued radical social reforms in conjunction with David Lloyd George (1863 â 1945), the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1909, he wrote Liberalism and the Social Problem, a collection of speeches in many respects anticipating the âwelfare stateâ of the post-Second World War era.

In 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary, where he was to prove somewhat controversial. A famous photograph from the time shows the impetuous Churchill taking personal charge of the January 1911 Sidney Street Siege, peering around a corner to view a gun battle between cornered anarchists and Scots Guards. His role attracted much criticism. The building under siege caught fire. Churchill denied the fire brigade access, forcing the criminals to choose surrender or death. Arthur Balfour asked, "He [Churchill] and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing but what was the Right Honourable gentleman doing?"

In 1911, Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty, a post he retained into the First World War. He gave impetus to military reform efforts, including development of naval aviation, tanks, and the switch in fuel from coal to oil, a massive engineering task, also reliant on securing Mesopotamia's oil rights, bought circa 1907 through the secret service using the Royal Burma Oil Company as a front company. The development of the battle tank was financed from naval research funds via the Landships Committee, and, although a decade later, development of the battle tank would be seen as a stroke of genius, at the time it was seen as misappropriation of funds. The battle tank was deployed ineptly in 1915, much to Churchill's annoyance. He wanted a fleet of tanks to surprise the Germans under cover of smoke, and to open a large section of the trenches by crushing barbed wire and creating a breakthrough sector.

Churchill was one of the political and military engineers of the disastrous Gallipoli landings on the Dardanelles during World War I, which led to his description as "the butcher of Gallipoli." When Asquith formed an all-party coalition government, the Conservatives demanded Churchill's demotion as the price for entry. For several months Churchill served in the non-portfolio job of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, before resigning from the government feeling his energies were not being used. He rejoined the army, though remaining an MP, and served for several months on the Western Front commanding a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front with the rank of colonel. During this period, his second in command was Archibald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso (1890 â 1970) who would later lead the Liberal Party.

Return to power

In December 1916, Asquith and the Conservative Party were ousted from power and were replaced by Lloyd George and the now-ruling Liberal Party. However, the time was thought not yet right to risk the Conservatives' wrath by bringing Churchill back into government. However, in July 1917, Churchill was appointed Minister of Munitions. After the end of the war Churchill served as both secretary of state for war and secretary of state for air (1919 â 1921). On the possible use of gas weapons (teargas) in quelling uprisings in the British League of Nations Mandate territories of the former Ottoman Empire, Churchill commented that while loss of life should be minimized, he did not see why gas should not be used âagainst uncivilized tribes.â

During this time (1919 â 1921), he undertook with surprising zeal the cutting of military expenditure. However, the major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Churchill was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle." He secured from a divided and loosely organized Cabinet an intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nationâand in the face of the bitter hostility from the Labour Party. In 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Churchill was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded Ukraine. He became secretary of state for the colonies in 1921 and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which established the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland).

Career between the wars

In October 1922, Churchill underwent an operation to remove his appendix. Upon his return, he learned that the government had fallen and a general election was looming. The Liberal Party was now beset by internal division and Churchill's campaign was weak. He lost his seat at Dundee to prohibitionist, Edwin Scrymgeour, quipping that he had lost his ministerial office, his seat, and his appendix all at once. Churchill stood for the Liberals again in the United Kingdom general election of 1923, losing in Leicester, but over the next twelve months he moved towards the Conservative Party, although initially using the labels "Anti-Socialist" and "Constitutionalist." Two years later, in the 1924 general election, he was elected to represent Epping (where there is now a statue of him) as a "Constitutionalist" with Conservative backing. The following year he formally rejoined the Conservative Party, commenting wryly that, "Anyone can rat [change parties], but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat."

He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924 (his father's former ministry) under Stanley Baldwin (1867 â 1947) and oversaw the United Kingdom's disastrous return to the gold standard, which resulted in deflation, unemployment, and the miners' strike that led to the General Strike of 1926. This decision prompted the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883 â 1964) to write The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, correctly arguing that the return to the gold standard would lead to a world depression. Churchill later regarded this as one of the worst decisions of his life. To be fair to him, it must be noted that he was not an economist and that he acted on the advice of the governor of the Bank of England, Montague Norman (of whom Keynes said: "Always so charming, always so wrong.").

During the General Strike of 1926, Churchill was reported to have suggested that machine guns be used on the striking miners. Churchill edited the government's newspaper, the British Gazette, and during the dispute he argued that "either the country will break the General Strike, or the General Strike will break the country." Furthermore, he was to controversially claim that the fascism of Benito Mussolini (1883 â 1945) had "rendered a service to the whole world," showing as it had "a way to combat subversive forces"âthat is, he considered the regime to be a bulwark against the perceived threat of communist revolution.

The Conservative government was defeated in the 1929 general election. In the next two years, Churchill became estranged from the Conservative leadership over the issues of protective tariffs and Indian Home Rule. When Ramsay MacDonald (1866 â 1937) formed the National Government in 1931, Churchill was not invited to join the Cabinet. He was now at the lowest point in his career, in a period known as "the wilderness years." He spent much of the next few years concentrating on his writing, including Marlborough: His Life and Timesâa biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlboroughâand A History of the English Speaking Peoples (which was not published until well after WWII). He became most notable for his outspoken opposition towards the granting of independence to India. In 1930, he infamously referred to Gandhi, the âseditious middle temple lawyerâ as a âhalf-naked fakir.â Gandhi wrote back that he would âhe would love to be a naked-fakir but was not one as yet.â A year later, the two men met face to face at the Indian round table conference, when Gandhi told Churchill that he had "an alternative that is unpleasant to youâŠIndia demands complete liberty and freedomâŠthe same liberty that Englishmen enjoyâŠand I want India to become a partner in the Empire. I want to partner with the English peopleâŠnot merely for mutual benefit, but so that the great weight that is crushing the world to atoms may be lifted from its shoulders." In fact, such a partnership was close to Churchill's own ideal, but he was too much a child of his time to recognize that his paternalistic attitude towards Indians was denying them the rights and freedoms he so cherished at home. He believed, as most Englishmen still did, that Britain still had a moral responsibility to âdischarge duties to [a] vast helpless populationâ (Lukacs 2002).

Soon though, his attention was drawn to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the dangers of Germany's rearmament. For a time he was a lone voice calling on Britain to strengthen itself and counter the belligerence of Germany. Churchill was a fierce critic of Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler. He was also an outspoken supporter of King Edward VIII during the Abdication Crisis, leading to some speculation that he might be appointed prime minister if the king refused to take Baldwin's advice and consequently the government resigned. However, this did not happen, and Churchill found himself politically isolated and bruised for some time after this.

Role as Wartime Prime Minister

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Churchill was again appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. In this job he proved to be one of the highest-profile ministers during the so-called "Phoney War," when the only noticeable action was at sea. Churchill advocated the preemptive occupation of the neutral Norwegian iron-ore port of Narvik and the iron mines in Sweden, early in the war. However, Chamberlain and the rest of the War Cabinet disagreed, and the operation was delayed until the German invasion of Norway, which was successful despite British efforts.

In May 1940, directly upon the German invasion of France by a surprising lightning advance through the Low Countries, it became clear that the country had no confidence in Chamberlain's prosecution of the war. Chamberlain resigned, and Churchill was appointed prime minister and formed an all-party government. In response to previous criticisms that there had been no clear single minister in charge of the prosecution of the war, he created and took the additional position of minister of defense. He immediately put his friend and confidant the industrialist and newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook in charge of aircraft production. It was Beaverbrook's astounding business acumen that allowed Britain to quickly gear up aircraft production and engineering that eventually made the difference in the war.

Churchill's speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled United Kingdom. He is said to have overcome a childhood stammer, traces of which can be heard in his speech. However, he is recognized as one of the truly great orators of the century. His first speech as prime minister was the famous "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat" speech. He followed that closely with two other equally famous ones, given just before the Battle of Britain. One included the immortal line, "We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender." The other included the equally famous "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, 'This was their finest hour.'" At the height of the Battle of Britain, his bracing survey of the situation included the memorable line "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few," which engendered the enduring nickname "The Few" for the Allied fighter pilots who won it.

His good relationship with U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt secured the United Kingdom vital supplies via the North Atlantic Ocean shipping routes. It was for this reason that Churchill was relieved when Roosevelt was re-elected. Upon re-election, Roosevelt immediately set about implementing a new method of not only providing military hardware to Britain without the need for monetary payment, but also of providing, free of fiscal charge, much of the shipping that transported the supplies. Put simply, Roosevelt persuaded Congress that repayment for this immensely costly service would take the form of defending the USA; and so lend-lease was born. Churchill had 12 military strategic conferences with Roosevelt, which covered the Atlantic Charter, Europe first strategy, the Declaration by the United Nations, and other war policies. Churchill initiated the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Hugh Dalton's ministry of economic warfare, which established, conducted and fostered covert, subversive, and partisan operations in occupied territories with notable success; and also the British Commandos, which established the pattern for most of the world's current special forces. The Russians referred to him as the "British Bulldog." In 1940, Britain stood alone (with her colonies) against Germany. Churchill used his friendship with Roosevelt to plead for U.S. support. Speaking on July 14, he said that Britain was âfighting by ourselves alone; but we are not fighting for ourselves aloneâ (Churchill 1940). He warned Roosevelt that he might face a Germany more numerous, better armed, and stronger than the New World, if Hitler won (June 15, 1940) (Lukacs 2002).

However, some of the military actions during the war remain controversial. Churchill was at best indifferent and perhaps complicit in the Great Bengal famine of 1943, which took the lives of at least 2.5 million Bengalis. Japanese troops were threatening British India after having successfully taken neighboring British Burma. Some consider the British government's policy of denying effective famine relief a deliberate and callous scorched earth policy adopted in the event of a successful Japanese invasion. Churchill supported the bombing of Dresden shortly before the end of the war; Dresden was primarily a civilian target with many refugees from the East and was of allegedly little military value. However, the bombing was helpful to the allied Soviets. Bishop Bell of Chichester (1883 â 1958) believed that the blanket bombing of Dresden endangered the âjustâ status of the war.

In July, Churchill requested from the Chief of Staff Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay, a study on the potential use of poison gas as a means of shortening the war or retaliating against the V-1 and V-2 rockets then falling on London:

I want you to think very seriously over this question of poison gas. I would not use it unless it could be shown either that (a) it was life or death for us, or (b) that it would shorten the war by a yearâŠ. If the bombardment of London became a serious nuisance and great rockets with far-reaching and devastating effect fell on many centres of Government and labour, I should be prepared to do anything that would hit the enemy in a murderous place. I may certainly have to ask you to support me in using poison gas. We could drench the cities of the Ruhr and many other cities in Germany in such a way that most of the population would be requiring constant medical attention. We could stop all work at the flying bomb starting points. I do not see why we should have the disadvantages of being the gentleman while they have all the advantages of being the cad. There are times when this may be so but not now (Prime Minister's Personal Minute, D.217/4, 6 July 1944).

The study concluded and advised Churchill that the use of such weapons would not benefit the war effort.

Churchill was party to treaties that would redraw post-WWII European and Asian boundaries. These were discussed as early as 1943. Proposals for European boundaries and settlements were officially agreed to by Harry S. Truman, Churchill, and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam Conference.

The settlement concerning the borders of Poland, i.e. the Curzon lineâboundary between Poland and the Soviet Union and Oder-Neisse lineâbetween Germany and Poland, was viewed as a betrayal in Poland during the post-war years, as it was established against the views of the Polish government in exile. Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless troubleâŠ. A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by these transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions." The transfers were in the end carried out in a way that resulted in hardship and death for many of those transferred. Churchill opposed the effective annexation of Poland by the Soviet Union and wrote bitterly about it in his books, but he was unable to prevent it at the conferences.

After World War II

Although the importance of Churchill's role in World War II was undeniable, he had many enemies in his own country. His expressed contempt for a number of popular ideas, in particular public health care and better education for the majority of the population, and produced much dissatisfaction amongst the population, particularly those who had fought in the war. Immediately following the close of the war in Europe, Churchill was heavily defeated at the 1945 general election by Clement Attlee (1883 â 1967) and the Labour Party. Some historians think that many British voters believed that the man who had led the nation so well in war was not the best man to lead it in peace. Others see the election result as a reaction against not Churchill personally, but against the Conservative Party's record in the 1930s under Baldwin and Chamberlain.

Winston Churchill was an early supporter of the pan-Europeanism that eventually led to the formation of the European Common Market and later the European Union (for which one of the three main buildings of the European Parliament is named in his honor). He believed that disunity was European's weakness, unity her strength. At Arnhem in 1956, he argued that, as a result of Western European unity, the nations of the East would also eventually gain their independence. However, Lukacs (2002) doubts that he would not have approved of a âfaceless, frequently powerless, largely bureaucratic âEuropean Unionââ (but adds that he would have welcomed the Channel Tunnel trains). Ramsden (2003) surmises that Churchill âvery probably deplored Britain's first application to join âEurope,â a policy which involved a turning away from the British Dominions, and to a certain extent away from the Special Relationship with the U.S. tooâ (4).

Churchill was instrumental in giving France a permanent seat on the UN Security Council (which provided another European power to counterbalance the Soviet Union's permanent seat). Churchill also occasionally made comments supportive of world government. For instance, in 1947 he said:

Unless some effective world supergovernment for the purpose of preventing war can be set upâŠthe prospects for peace and human progress are darkâŠ. [If] it is found possible to build a world organization of irresistible force and inviolable authority for the purpose of securing peace, there are no limits to the blessings which all men enjoy and share (Churchill 1998: 913).

At the beginning of the Cold War, he famously mentioned the "Iron Curtain," a phrase originally created by Joseph Goebbels. The phrase entered the public consciousness after a 1946 speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, when Churchill, a guest of Harry S. Truman, famously declared:

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Poland, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere.

Second term

Churchill was restless and bored as leader of the Conservative opposition in the immediate post-war years. After Labour's defeat in the general election of 1951, Churchill again became prime minister. His third governmentâafter the wartime national government and the short caretaker government of 1945âwould last until his resignation in 1955. During this period he renewed what he called the "special relationship" between Britain and the United States, and engaged himself in the formation of the post-war order.

His domestic priorities were, however, overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises, which were partly the result of the continued decline of British military and imperial prestige and power. Being a strong proponent of Britain as an international power, Churchill would often meet such moments with direct action. Three crises had to be dealt with, all arising from imperial embroilment. First, in 1951, the Iranian parliament voted to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company under the leadership of Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh. Churchill favored the democratic developments in Iran but wanted to retain the privileges and revenue enjoyed by the oil company. Finally, in 1953, with the support of the U.S. under Dwight D. Eisenhower, the British and Americans backed a coup that toppled the elected government and returned power to the shah. Second, in 1952, the Mau Mau rebellion against British rule started in Kenya. Churchill ordered an increased military presence and appointed General Sir George Erskine, who would implement Operation Anvil in 1954 that broke the back of the rebellion in the city of Nairobi. Operation Hammer, in turn, was designed to root out rebels in the countryside. Churchill ordered peace talks opened, but these collapsed shortly after his leaving office. Third, Churchill had to deal with the Malayan Emergency as agitation for independence increased (with some Soviet involvement). Slowly, the rebellion was squashed, but it was equally clear that colonial rule from Britain was no longer tenable. In 1953, plans were drawn up for independence for Singapore and the other Crown colonies in the area. The first elections were held in 1955, just days before Churchill's own resignation, and by 1957, under Prime Minister Anthony Eden (1897 â 1977), Malaysia became independent.

Honors for Churchill

In 1953, he was awarded two major honors: he was invested as a Knight of the Garter (becoming Sir Winston Churchill, KG) and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values." It has been called an open secret that he would have preferred the Peace Prize. A stroke in June of that year led to him being paralyzed down his left side. He retired because of his health on April 5, 1955, but retained his post as Chancellor of the University of Bristol.

In 1955, Churchill was offered elevation to dukedom as the first-ever Duke of London, a title he himself selected. However, he then declined the title after being persuaded by his son Randolph Churchill not to accept it. Since then, no people other than royalty have ever been offered a dukedom in the United Kingdom.

In 1956, Churchill received the Karlspreis (Charlemagne Award), an award by the German city of Aachen to those who most contribute to the European idea and European peace. In 1959, he became Father of the House, the MP with the longest continuous service. He was to hold the position until his retirement from the Commons in 1964. He became the first person to receive honorary U.S. citizenship in 1963. From 1941 to his death, he was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a ceremonial office.

Family

On September 2, 1908, at the socially desirable St. Margaret's, Westminster, Churchill married Clementine Churchill, Baroness Spencer-Churchill, a dazzling but largely penniless beauty whom he met at a dinner party that March (he had proposed to actress Ethel Barrymore but was turned down). They had five children: Diana Churchill; Randolph Frederick Edward Churchill; Sarah Millicent Hermione Churchill, who co-starred with Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding; Marigold Frances Churchill, who died in early childhood; and Mary Churchill, who has written a book on her parents.

Clementine's mother was Lady Blanche Henrietta Ogilvy, second wife of Sir Henry Montague Hozier and a daughter of the 7th Earl of Airlie. Clementine's paternity, however, is open to healthy debate. Lady Blanche was well-known for sharing her favors and was eventually divorced as a result. She maintained that Clementine's father was Capt. William George "Bay" Middleton, a noted horseman. But Clementine's biographer Joan Hardwick has surmised, due to Sir Henry Hozier's reputed sterility, that all Lady Blanche's "Hozier" children were actually fathered by her sister's husband, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, better known as a grandfather of the infamous Mitford sisters of the 1920s.

Churchill's son Randolph and his grandsons Nicholas Soames and Winston Churchill all followed him into Parliament.

When not in London on government business, Churchill usually lived at his beloved Chartwell House in Kent, two miles south of Westerham. He and his wife bought the house in 1922 and lived there until his death in 1965. During his Chartwell stays, he enjoyed writing there, as well as painting, bricklaying, and admiring the estate's famous black swans. It has been claimed that Churchill had few close friends but many âchumsâ and that he was distant from his own children, as he had been from his father. On the other hand, his children were fiercely loyal to him (as are his grandchildren). His grandson, Winston Churchill, is a trustee of the Churchill Center in Washington, DC (founded 1994). Randolph co-wrote a biography (Churchill and Gilbert, 8 volumes) known as an âofficial biographyâ because Sir Winston had blessed the project, âI should be happy that you should write my official biography when the time comesâ (May 1960).

Last days

In 1953, Churchill suffered a stroke. Aware that he was slowing down both physically and mentally, Churchill retired as prime minister in 1955 and was succeeded by Anthony Eden, who had long been his ambitious protégée. (Three years earlier, Eden had married Churchill's niece Anna Clarissa Churchill, his second marriage.) Churchill spent most of his retirement at Chartwell and in the south of France. After breaking his leg in 1962, he was rarely seen in public (Ramsden 2003: 6).

In 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy named Churchill the first Honorary Citizen of the United States. Churchill was too ill to attend the White House ceremony. His son and grandson accepted the award for him.

On January 15, 1965 Churchill suffered another strokeâa severe cerebral thrombosisâthat left him gravely ill. He died nine days later on January 24, 1965, 70 years to the day of his father's death. His body lay in state in Westminster Hall for three days and a state funeral service was held at St. Paul's Cathedral. This was the first state funeral for a non-royal family member since that of Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts of Kandahar in 1914, and was staged at the queen's own request. As Churchill's coffin passed down the Thames on a boat, the cranes of London's docklands bowed in salute. The Royal Artillery fired a 19-gun salute (as head of government), and the Royal Air Force staged a fly-by of 16 English Electric Lightning fighters. The state funeral, which âhad no precedent in living memory except those of the Windsor monarchsâ (Ramsden 2003: 5) was the largest gathering of dignitaries in Britain as representatives from over 100 countries attended, including French President Charles de Gaulle, who is reported to have said, with regret ânow Britain is no longer a great powerâ (Ramsden 2003: 3). Also in attendance was Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson, plus other heads of state and government and members of royalty. It saw the largest assemblage of statesmen in the world until the funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005. Queen Victoria's gun-carriage was used to carry the coffin.

It has been suggested it was Churchill's wish that, were de Gaulle to outlive him, his (Churchill's) funeral procession should pass through Waterloo Station. This is complete myth. Though of course President de Gaulle did indeed attend the service and the coffin departed for Bladon from Waterloo Station, there is absolutely no connection. In fact, Churchill did not plan his own funeral as commonly believed; he made a few suggestions, but there was a private committee that made the plans, and he was not on it.

At Churchill's request, he was buried in the family plot at Saint Martin's Churchyard, Bladon, near Woodstock and not far from his birthplace at Blenheim.

Because the funeral took place on January 30, people in the United States marked Churchill's funeral by paying tribute to his friendship with Roosevelt because it was the anniversary of FDR's birth.

Religious Beliefs

Lukacs (2002) says that Churchill was not a âreligious man.â However, he had a profound sense of his own destiny and saw himself as defending Christian civilization from tyranny âat a dramatic moment in the twentieth centuryâ (17â18). In the darkest days of 1940, he wrote to Franklin Roosevelt that London was a âstrong City of Refuge which enshrines the title deeds of human progress and is of deep consequence to Christian civilizationâ (95). In his first speech to Parliament as prime minister, he referred to the need for God's strength if Britain was to rise to the challenge she faced:

I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweatâŠ. You ask what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war by sea, land and air with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us: to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road will be; for without victory, there is no survival.

In 1955, when he gave his farewell speech in Parliament, he again made reference to God, as he asked:

Which way shall we turn to save out lives and the future of the world? It does not matter so much for old people: they are going soon away; but I find it poignant to look at youth in all its activity and ardourâŠand wonder what would lie before them if God wearied of mankind (18).

During his days in India, he reflected on the existence of different creeds, including numerous in India, and concluded that, âif you tried your best to live an honourable life and did your duty and were faithful to friends and not unkind to the weak and poor, it did not matter much what you believed or disbelieved.â This, he continued, would ânowadaysâŠbe called the âReligion of Health-mindedness'â (1996: 115â116). Churchill seemed to have had some sort of prescience that humanity must do its own part to create peace, else God may get tired of waiting for his creatures to mature and assume responsibility for âtilling the earth.â Churchill did not think it very profitable to try to reconcile modern science and historical knowledge of âthe Biblical story,â since what mattered was receiving a âmessage [that] cheers your heart.â âToo much religion,â he said, âof any kindâŠwas a bad thingâ (1996: 115â116).

Churchill as writer and historian

Assessment

Churchill was a prolific writer throughout his life and, during his periods out of office, regarded himself as a professional writer who was also a member of Parliament. Despite his aristocratic birth, he inherited little money (his mother spent most of his inheritance) and always needed ready cash to maintain his lavish lifestyle and to compensate for a number of failed investments. Some of his historical works, such as A History of the English Speaking Peoples, were written primarily to raise money, but this should not detract from the value of his literary legacy. He wrote several autobiographical works, biographies of his father and of the first Duke of Marlborough, a history of the First World WarâThe World Crisis (six volumes, 1923 â 1931)âand of WWIIâSecond World War (six volumes, 1948 â 1953), and his History of the English-Speaking Peoples (four volumes, 1956 â 1958), much of which had been written in the 1930s. These are among the longest works of history ever published (Second World War runs to more than two million words), and earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Although Churchill was not a trained historian, he was an excellent writer. In his youth he was an avid reader of history, but within a narrow range. The major influences on his historical thought, and his prose style, were Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon's history of the English Civil War, Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and Macaulay's History of England. Lukacs (2002) says that while Churchill was influenced by these historians, âhe did not emulate themâ (125). On a critical note, he had no knowledge of, or interest in, social or economic history, and he always saw history as essentially political and military, driven by great men rather than by economic forces or social change.

Churchill has been called the last (and one of the most influential) exponents of "Whig history"âthe belief of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Whig Party that the British people had a unique greatness and an imperial destiny, and that all British history should be seen as progress towards fulfilling that destiny. This belief inspired his political career as well as his historical writing. It was an old-fashioned view of history even in Churchill's youth and he never modified it or showed any interest in other schools of history. On the other hand, Britain did, at this time, have an important role to play and Churchill himself acted a not insignificant part in many world events. Although he employed professional historians as assistants, they had no influence over the content of his works. His books have been described as amateur but Lukacs (2002) thinks it unfair to compare him with university-based historians âwhoseâŠwork is often the result of tasks they had farmed out to their graduate students,â suggesting that his flair for language, gift of summary, and careful use of sources qualify him as a âgreat historianâ (111â112). Some of his masterful passages should âinspire historians as long as English history is written.â Churchill's histories were also âworks of artâ and he wrote them because he was interested in history and he was conscious that he was also making history (114). Ramsden (2003) comments that though âbilled as personal accounts,â Churchill's books had the added âauthority of a man who made the history before writing itâ (198). Lukacs says, âStunning passages and phrases are abundant in every one of his booksâ (125). He was a âmaker of history whose mind was steeped in history.â

Churchill deliberately chose topics that were of personal interest, either biographies of members of his family or events in which he was himself an actor, and he used his own experience, and sometimes defended his actions in his writing (111). He was conscious that history would examine and judge him (125). âIn the preface of both his world war histories,â says Lukacs, âhe wrote that he followed âas far as I am able, the method of Defoe's Memoirs of a Cavalier, in which the author hangs the chronicle and discussion of great military and political events upon the thread of the personal experiences of an individual.ââ This method was then complemented by what Lukacs describes as almost too âcopiousâ notes in all of his worksâsuggesting at least an amateur historians respect for primary sources. There is, indeed, âevidence of assiduous attempts at researchâ (106). His mistake was to try to tell everything. His speeches, in contrast, were short and stirring; his books were too long. Churchill did not hesitate to use his access to documents to aid his research. As a Cabinet minister for part of the First World War and as prime minister for nearly all of the Second, he had unique access to official documents, military plans, official secrets, and correspondence between world leaders. After the First World War, when there were few rules governing these documents, he simply took many of them with him when he left office and used them freely in his booksâas did other wartime politicians such as David Lloyd George. As a result of this, strict rules were put in place preventing Cabinet ministers using official documents for writing history or memoirs once they left office.

Limitations of Churchill's Historianship

Churchill was himself aware of the âlimitations of his historianshipâ (Lukacs 2002: 104â105). In part, while his unique position as a former prime minister and a serving politician helped him with access to documentation, this also meant that he was precluded from revealing certain information. For example, he could not reveal military secrets, such as the work of the code-breakers at Bletchley Park or the planning of the atomic bomb. Thus it can be said that his histories are not as complete as later works. He could not discuss wartime disputes with figures such as Dwight Eisenhower, Charles de Gaulle, or Tito, since they were still world leaders at the time he was writing. He could not discuss Cabinet disputes with Labour leaders such as Attlee, whose goodwill the project depended on. He could not reflect on the deficiencies of generals such as Archibald Wavell or Claude Auchinleck for fear they might sue him (some, indeed, threatened to do so). Other deficiencies were of Churchill's own making. Although he described the fighting on the Eastern Front, he had little real interest in it and no access to Soviet or German documents, so his account is a pastiche of secondary sources, largely written by his assistants. The same is true to some extent of the war in the Pacific except for episodes such as the fall of Singapore in which he was involved. His account of the U.S. naval war in the Pacific was so heavily based on other writers that he was accused of plagiarism.

The real focus of Churchill's work was always on the war in Western Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa, but here his work is based heavily on his own documents, so it greatly exaggerates his own role. He had little access to American documents, and even those he did have, such as his letters from Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower, had to be used with caution for diplomatic reasons. Although he was, of course, a central figure in the war, he was not as central as his books suggest. Although he is usually fair, some personal vendettas are airedâagainst Stafford Cripps, for example. The Second World War can still be read with great profit by students of the period, provided it is seen mainly as a memoir by a leading participant rather than as an authoritative history by a professional and detached historian. The war, and particularly the period between 1940 and 1942 when Britain was fighting alone, was the climax of Churchill's career, and his personal account of the inside story of those days is unique and invaluable. But since the archives have been opened, far more accurate and reliable histories have been written.

Churchill's World Vision

Churchill's History of the English-Speaking Peoples was commissioned and largely written in the 1930s when Churchill badly needed money, but it was put aside when war broke out in 1939, being finally issued after he left office for the last time in 1955. Although it contains much fine writing, it shows Churchill's deficiencies as a historian at their most glaring. This work has been criticized as rather old-fashioned and as light on such significant events as the Industrial Revolution while too heavy on the lives of kings and queens. However, the work was motivated from start to finish by Churchill's vision of a worldwide union of English-speaking peoples, a dream that infused his whole life. His vision was of a federation of the English-speaking people, followed by âanother Age of Antonimes, movement forward to the sunny uplands of a democratic world order, buttressed by the mild and benevolent global and maritime primacy of the English-speaking people.â This was consistently his vision, âfrom the very beginning to the very end of his public lifeâ (Lukacs 2002: 15). Thus, the history was not merely about the past. This is why the relation, or the special relation, with the U.S. was so important to him. Of course, his mother was American. His interest in the U.S. was âhistorical more than racial, civilizational more than culturalâ (16) and he was also aware that Britain's efforts in two world wars had so drained the nation that Britain's role in the world would in many ways pass to the U.S. He fully recognized that part of the price for the survival of âBritish independence and of democracy was the eventual transference of much of the imperial burden to the Americansâ (Lukacs 2002: 95) and although he was very reluctant to oversee the end of the empire, he pragmatically knew that it could not continue.

Legacy

Praise for Churchill accompanied his funeral. Arthur Briant of the Illustrate News observed, âthe age of giants has gone for everâŠfor no one who can remember 1940 and the Second World War can expect to see in his lifetime anyone of the stature of this colossus of a manâ (Ramsden 2003: 1). Dwight Eisenhower, who counted Churchill as a friend, said, as he watched the funeral cortege:

In the coming years, many in countless words will strive to interpret the motives, describe the accomplishments, and extol the virtues of Winston Churchillâsoldier, statesman, and citizen that two great countries were proud to claim as their own. Among all the things so written or spoken, there will ring out through all the centuries one incontestable refrain: Here was a champion of freedom (Plumpton 2009).

His wartime colleague and successor as prime minister, Clement Attlee (first Labour PM to serve for a full term), who defeated Churchill in the 1945 election, wrote:

By any reckoning, Winston Churchill was one of the greatest men that history recordsâŠ. Energy and poetry, in my view, really sum him up. He was, of course, above all, a supremely fortunate mortal (Best 2001: 334).

Leadership during World War II

Lukacs (2002) suggests that few are aware how close Hitler came to winning World War II and that Churchill was uniquely able to rise to the moment; âHe was extraordinaryâŠno one else could have done what he did in 1940â (1). Eminent historian, A. J. P. Taylor said that âhistorians of the future would ignore at their peril the spiritual contact which one man found in 1940 with the rest of his fellow-countrymenâ (Lukacs 2002: 111). Hitler passionately hated Churchill and the idea that some sort of appeasement might have avoided World War II needs to take stock of Hitler's imperial ambitions as set out in Mein Kampf where he wrote that if Germany:

Feels itself to be the purest embodiment of the value of race and personality and conducts itself accordingly, it will with almost mathematical certainty some day emerge victorious from its struggle. Just as Germany must inevitably win her rightful position on this earth if she is led and organized according to the same principles.

A state which in this age of racial poisoning dedicates itself to the care of its best racial elements must some day become lord of the earth (Hitler, Conclusion Mein Kampf Volume Two: The National Socialist Movement. Retrieved September 30, 2012.).

Negotiation with Hitler would have meant conceding territory, which no nation had the power to do.

Three Main Criticisms

In addition to the issue of appeasement, three main criticisms of Churchill are commonly cited: his changing of political allegiance; his opposition to Indian independence; and some dubious military and peacetime decisions.

One response to the first issue is that, while he did change party political allegiance, he remained consistently committed to the same progressive âimperial liberalâ ideals. He was supportive of social reform, which was one of the main reasons for his initial change of party. He has also been described as an âEdwardian humanitarianâ (Best 2001: 330). Biographer Geoffrey Best (2001) points out that while party loyalty has been considered a British politicianâs principal virtue, Churchill's main interest was in policy. Thus, when the Conservatives refused to change their social policy, he joined the Liberals but when the Liberals grew in his view too close to socialism, he left the Liberals. Best accepts, though, that Churchill's overriding concern was to rejoin government. Belief in âthat somewhat mystical âdestinyâ to which he recurrently referredâ drove him to what others saw as opportunistic change of party. He was not really a party creature but pragmatically âhad to operate with partiesâŠif he was to hold officeâ (22). Party loyalty, too, may not be such a high moral virtue in a âsystems of proportional representation, for which coalitions of parties and malleable government hold no such horrorsâ (22â23). Indeed, the fact that Churchill had served in the government of two political parties may have equipped him to lead the national coalition government during World War II. Roy Jenkins (2002) who himself left one party to co-found another began his book on Churchill thinking that William Ewart Gladstone was the greater prime minister but changed his mind: âwith all his idiosyncrasies, his indulgences, his occasional childishness, but also his genius, his tenacity, and persistent ability, right or wrong, successful or unsuccessfulâ Churchill was the greatest human being to âoccupy 10 Downing Streetâ (912).

On Indian independence, Churchill was wrong but he was not the only Englishman who seemed blind to the inconsistency and hypocrisy that Indians saw all too clearly. On the one hand, English literature and rhetoric spoke of freedom and equality, democracy and dignity, yet the English's paternalistic attitude could not concede that non-whites were mature enough to enjoy these rights. Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian writer, poet, and philosopher, pointed out how early in their careers he and other Home Rule advocates âhad not lost faith in the generosity of the English race,â since it had been English literature that introduced them to âliberal humanism [and] England at that time gave refuge to people fleeing persecution and afforded political martyrsâŠan unreserved welcomeâ (Nehru 2005: 321). This faith was lost when they discovered how those who âaccepted the highest truths of civilization disowned them with impunity whenever questions of national self-interest were involvedâ (322). Meacham (2003) suggests that both Churchill and Roosevelt âwere largely creatures of their time on questions of race and ethnicityâ but observes that âtheir overriding concern [for the] preservation of those forces and institutionsâthe American and British understandings of justice and fair play [ultimately] moved us to higher ground,â that is, the ground occupied by Tagore and Gandhi (239).

On the issue of questionable military decisions, it can be pointed out that General Kitchener and the Cabinet supported the decision to land troops on the Dardanelles, which they believed necessary to prevent a Turkish attack on Egypt (see Best 2001: 63). The initial idea, though, had been his own. In contrast, the disastrous and much criticized return to the gold standard of 1925 was not Churchill's idea but that of conservative economic advisors and he had been reluctant to follow this advice, although eventually did so.

Political Influence

Churchill's progressive views on such issues as social reform and his tendency to move towards the center on many issues remain important in contemporary politics. Ramsden (2003) explored Churchill's political legacy within the USA, where his status as an honorary citizen makes him for some a national, not a foreign, statesmen. President George W. Bush had âa bust of Churchill in the oval office [and] liberallyâ quoted him in his own ârhetorical efforts to roll the West against terrorismâ (587). Former Mayor Guilliani of New York behaved in an âavowedly Churchillian manner,â and was dubbed by the Washington Post as a âChurchill in a Yankees capâ following the tragic events of 9/11. The alliance between British Prime Minister Tony Blair and George Bush in the âwar on terrorâ has been compared with that between Churchill and Roosevelt, thus Churchill's political legacy continues to be taken âwarmly to heartâ and gives âcontinuing inspirationâ to sections of the American people especially as a symbol of Anglo-American solidarity (585).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Best, Geoffrey. 2001. Churchill: A Study in Greatness. London: Hambledon and London. ISBN 1852852534

- Churchill, Winston. [1930] 1996. My Early Life. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684823454

- Churchill, Winston. 1940. War of the Unknown Warriors BBC Broadcast, London. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- Churchill, Winston. 1998. Churchill Speaks, 1897-1963: Collected Speeches in Peace and War. Barnes and Noble. ISBN 978-0760708958

- Gilbert, Martin. 1992. Churchill: A Life. New York: Henry Holt & Co./Owl Books. ISBN 0805023968

- Gilbert, Martin. 1997. In Search of Churchill: A Historian's Journey. New York, NY: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471180722

- Haffner, Sebastian. 2003. Churchill: Life and Times. London: Haus Publishers. ISBN 1904341071

- Jenkins, Roy. 2002. Churchill. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux/Plume. ISBN 0374123543

- Lukacs, John. 2002. Churchill: Visionary. Statesman. Historian. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300097697

- Nehru, Jawaharlal. 2005. The Discovery of India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195623592

- Manchester, William. 1983. The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory 1874â1932. New York: Little, Brown (vol. 1). ISBN 0316545031

- Manchester, William. 1988. The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Alone 1932â1940. New York: Little, Brown (vol. 2). ISBN 0316545120

- Massie, Robert. 1991. Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War. New York: Random House. ISBN 1844135284

- Meacham, Jon. 2003. Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship. New York: Random House. ISBN 0812972821

- Muller, James W. 2009. The Education of Winston Churchill The Churchill Center Inc. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- The Oxford Dictionary of 20th Century Quotations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198601034

- Pelling, Henry. 1974. Winston Churchill. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0333124995

- Plumpton, John G. 2009. Operation Hopenot: The Funeral of Sir Winston S. Churchill Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- Ramsden, John. 2003. Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and his Legend Since 1945. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231131062

External links

All links retrieved May 17, 2023.

- The Churchill Centre website

- Winston Churchill in Cuba

- Churchill and the Great Republic Exhibition explores Churchill's lifelong relationship with the United States.

- Downloadable speeches by Churchill

|

1951: PĂ€r Lagerkvist | 1952: François Mauriac | 1953: Winston Churchill | 1954: Ernest Hemingway | 1955: HalldĂłr Laxness | 1956: Juan RamĂłn JimĂ©nez | 1957: Albert Camus | 1958: Boris Pasternak | 1959: Salvatore Quasimodo | 1960: Saint-John Perse | 1961: Ivo AndriÄ | 1962: John Steinbeck | 1963: Giorgos Seferis | 1964: Jean-Paul Sartre | 1965: Michail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov | 1966: Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Nelly Sachs | 1967: Miguel Ăngel Asturias | 1968: Yasunari Kawabata | 1969: Samuel Beckett | 1970: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn | 1971: Pablo Neruda | 1972: Heinrich Böll | 1973: Patrick White | 1974: Eyvind Johnson, Harry Martinson | 1975: Eugenio Montale |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.