| |

| Office | General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union / Premier of the Soviet Union |

| Term of Office | 1924 - 1953 |

| Predecessor | Vyacheslav Molotov (Premier) |

| Successor | Georgy Malenkov (Premier), Nikita Khrushchev (First Secretary) |

| Date of Birth | December 18, 1878 |

| Place of Birth | Gori, Georgia, Russian Empire |

| Date of Death | March 5, 1953 |

| Place of Death | Moscow, USSR |

| Political Party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

Iosif Vissarionovič Stalin, born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, December 18, 1878 (O.S. December 6)[1] – March 5, 1953, usually transliterated Josef Stalin, consolidated power to become the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union between 1928 and his death in 1953. Stalin held the title General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922-1953), a position that did not originally have significant influence, but through Stalin's ascendancy, became that of party leader and de facto leader of the Soviet Union.

Stalin was responsible transforming the Soviet Union from an agricultural nation into a global superpower and did not see the elimination of millions of lives as an impediment to the achievement of this goal. Many intellectuals, dissidents and even many allies were put to death under Stalin. Stalin's expansionism at the conclusion of World War II resulted in the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) by the West. In turn, Stalin gathered the Eastern European nations that were absorbed into the Soviet sphere after the Second World War under the umbrella of the Warsaw Pact. This, in turn, led to the Cold War and to the periodic international crises and the endless exchanges of hostile rhetoric in United Nations leadership circles until the final years of the Soviet Union.

Introduction

Born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, Stalin became General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in 1922. Following the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, he successfully maneuvered to defeat Leon Trotsky in a leadership struggle. Throughout his long period in office, he deftly built useful alliances within the Party, identified potential threats to his rule and established a reputation for eliminating those who did not share his convictions. Even Leon Trotsky fell victim to Stalin's assassins in 1940 when he was brutally stabbed to death in Mexico in 1940.

Stalin's rule was even more repressive and brutal than Lenin's. Unlike Lenin, Stalin encouraged and fostered a cult of personality, which portrayed Lenin as the father of the nation and Stalin as the faithful one who brought Lenin's dreams closer to fruition. Stalin's tactics and methodology or Stalinism, as it has come to be known, had long range effects on the features that characterized the Soviet state. Although Mao Zedong had serious issues with Stalin and the way in which Stalin treated him, Maoists, anti-revisionists and some others maintained, following Nikita Khrushchev's rise to power, asserted that Stalin was actually the last legitimate Socialist leader in the Soviet Union's history. Stalin claimed his policies were based on Marxism-Leninism, but there can be no doubt that Stalin actively sought to establish his own special place in world history.

Soon after assuming power, Stalin replaced Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP) of the 1920s, which allowed for some privatization, with Communist Party guided Five-Year Plans in 1928 and he implemented collective farming at roughly the same time, which resulted in millions dying of hunger in the 1930s. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union made significant progress from its former status as a predominantly peasant society to the status of a major world power by the end of the 1930s.

Collectivization which led to the State's Confiscation of grain and other food sources by Soviet authorities resulted in a major famine between 1932 and 1934, especially in the key agricultural regions including Ukraine, Kazakhstan and North Caucasus. This led to millions of Soviet citizens, indeed entire families, dying of starvation. Many peasants resisted collectivization and grain confiscations, but were repressed. Stalin had a special commitment to tightening control over and indeed decimating the most prosperous peasant class known as "kulaks."

Stalin was duped by Adolf Hitler and saw the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 as a commitment in which Hitler and Stalin recognized that they shared common ideological views on a number of matters. The pact was seen by Stalin as a guarantee against a Nazi attack on the Soviet Union. However, when things did not go well for Hitler in his war against Britain, he caught Stalin by surprise when he attacked the Soviet Union in 1940. The Soviets bravely resisted; however, they bore the brunt of the Nazis' attacks (around 75 percent of the Wehrmacht's forces). Soviet forces under Stalin and with massive military aid from the West, made a decisive contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II (known in the USSR as the "Great Patriotic War," 1941–1945). After the war, the USSR established itself under Stalin as one of the two major superpowers in the world, a position it maintained for the next four and a half decades.

Stalin's rule - reinforced by a cult of personality - fought real and alleged opponents mainly through the security apparatus, such as the NKVD. Nikita Khrushchev, one of Stalin's supporters in life and his eventual successor, chose to denounce Stalin's rule, his cult of personality and his brutal, genocidal rule at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR in 1956. Khrushchev initiated the "de-Stalinization" and Mao used Khrushchev's handling of Stalin as one of the rationales for the Sino-Soviet Split, which took place in 1960.

Childhood and early years

Reliable sources about Stalin's youth are few; however even those sources were subjected to censorship, a common practice during Stalin's reign. Some consider the writings of Stalin's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva to be the most reliable sources, since they were not censored.

Joseph Stalin was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in Gori, Georgia, Russian Empire to Vissarion Dzhugashvili and Ekaterina Geladze. In 1913, he adopted the name "Stalin," which is derived from the Russian (stal’) for "steel." His mother was born a serf. Stalin's three siblings died young; "Soso" (the Georgian pet name for Joseph), was effectively an only child. According to the official version, his father Vissarion was a cobbler. He opened his own shop, but quickly went bankrupt, forcing him to work in a shoe factory in Tiflis. Rarely seeing his family and drinking heavily, Vissarion is said to have been physically abusive toward his wife and small son Josef. One of Stalin's friends from childhood later wrote, "Those undeserved and fearful beatings made the boy as hard and heartless as his father." The same friend also wrote that he never saw him cry.

Another of his childhood friends, Ioseb Iremashvili, felt that the beatings by Stalin's father gave him a hatred of authority. He also said that anyone with power over others reminded Stalin of his father's cruelty. Stalin had broken his arm several times in the course of his life. There have been reports of Stalin having one arm shorter than the other. He also survived smallpox, that left pockmarks on his face.

One of the people for whom Ekaterina did laundry and house-cleaning was a Gori Jew, David Papismedov. Papismedov is said to have given Josef, who would help his mother, money and books to read, and encouraged him. Decades later, Papismedov came to the Kremlin to learn what had become of little "Soso." Stalin surprised his colleagues by not only receiving the elderly man, but happily chatting with him in public places.

In 1888, Stalin's father left to live in Tiflis, leaving the family without support. Rumors said he died in a drunken bar fight; however, others said they had seen him in Georgia as late as 1931. At the age of eight, "Soso" began his education at the Gori Church School.

When attending school in Gori, "Soso" was among a very diverse group of students. Joseph and most of his classmates were Georgian and spoke mostly Georgian. However, at school they were forced to use Russian. Even when speaking in Russian, their Russian teachers mocked Joseph and his classmates because of their Georgian accents. His peers were mostly the sons of affluent priests, officials, and merchants.

During his childhood, Joseph was fascinated by stories he read telling of Georgian mountaineers who valiantly fought for Georgian independence. His favorite hero in these stories was a legendary mountain ranger named Koba, which became Stalin's first alias as a revolutionary. He graduated first in his class and at the age of 14 he was awarded a scholarship to the Seminary of Tiflis, a Jesuit institution (one of his classmates was Krikor Bedros Aghajanian, the future Grégoire-Pierre Cardinal Agagianian) which he attended from 1894 to 1899. Although his mother wanted him to be a priest (even after he had become leader of the Soviet Union), he attended seminary not because of any religious vocation, but because of the lack of locally available university education. Stalin received a small stipend from the seminary for singing in the choir.

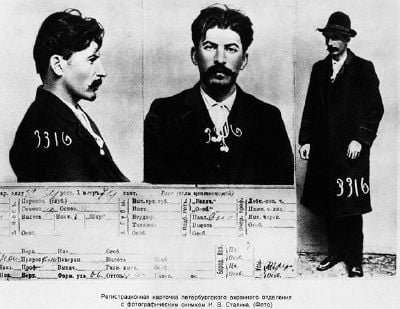

Stalin's involvement with the socialist movement (or, to be more exact, the branch of it that later became the communist movement) began at the seminary at the age of 15. The discipline and regime of the institution no doubt contributed to his determination to become revolutionary. During these school years, Stalin joined a Georgian Social-Democratic organization, and began propagating Marxism. Stalin quit the seminary in 1899 just before his final examinations; official biographies preferred to state that he was expelled.[2] He then worked for a decade with the political underground in the Caucasus, experiencing repeated arrests as well as exile to Siberia between 1902 and 1917.

Stalin supported Vladimir Lenin's doctrine of a strong centralist party of professional revolutionaries versus the less disciplined views of Karl Kautsky. His personal meetings with Lenin led him to embrace Bolshevism and Lenin's belief that the Soviet Union could precede smoothly under communist rule from a feudal to a socialist state without ceding power to accomodate a capitalist state prior to the emergence of socialism as the Mensheviks proposed. Stalin and Lenin attended the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1907[3]

In the period after the failed Revolution against the Czar in 1905 Stalin is said to led "fighting squads" in bank robberies to raise funds for the Bolshevik Party. His practical experience made him useful to the party, and gained him a place on its Central Committee in January 1912.

Stalin's major contribution to the development of the Marxist theory was a treatise, written while he was briefly in exile in Vienna, Marxism and the National Question. It presents an orthodox Marxist position (c.f. Lenin's On the Right of Nations to Self-Determination[4]). This treatise may have contributed to his appointment as People's Commissar for Nationalities Affairs after the revolution, as he was seen as a specialist in national problems.

In 1901, the Georgian clergyman M. Kelendzheridze wrote an educational book on language arts and included one of Stalin’s poems, signed by 'Soselo'. In 1907 the same editor published “A Georgian Chrestomathy, or collection of the best examples of Georgian literature”; Volume 1 included a poem of Stalin’s dedicated to Rafael Eristavi, on page 43. His poetry can still be seen in the Stalin Museum in Gori.

Marriages and family

Stalin's first wife, Ekaterina Svanidze, died in 1907, only four years after their marriage. At her funeral, Stalin allegedly said that with her death died also his last warm feelings for humankind. Only she had succeeded in melting his 'stony heart'. To him, her life was the only thing that made him happy. They had a son together, Yakov Dzhugashvili, with whom Stalin did not get along in later years.

Stalin's son Yakov is said to have shot himself because of the mistreatment he endured from his father. Nevertheless he did survive. Yakov served in the Red Army during World War II and was captured by the Germans. They offered to exchange him for Fieldmarshal Paulus, but Stalin turned the offer down, allegedly saying "A lieutenant is not worth a general." Others credit him with saying "I have no son," to this offer, and Yakov is rumored to have been accidentally electrocuted in the German prison camp where he was being held.

According to an article December 13, 2001 in The New York Times, "Of the roughly 30,000 wartime victims at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Nazi Germany, most were Russian prisoners of war, among them Stalin's oldest son." Stalin may have hesitated to seek a special arrangement to spare his son because he feared that it would have undermined support for his war efforts.

His second wife was Nadezhda Alliluyeva-Stalina, who died in 1932; she may have committed suicide by shooting herself after a quarrel with Stalin, leaving a suicide note which according to their daughter was "partly personal, partly political."[5][6][7]

Officially, she was said to have died of an illness. Stalin had two children with his second wife: a son, Vassili, and a daughter, Svetlana.

Vassili rose through the ranks of the Soviet air force and died in 1962. He distinguished himself in World War II as a capable airman. Svetlana emigrated to the United States in 1967 and later returned to the Soviet Union.

In his book The Wolf of the Kremlin, Stuart Kahan claimed that Stalin was secretly married to a third wife named Rosa Kaganovich.[8] Rosa was the sister of Lazar Kaganovich, a Soviet political leader. However, the claim is unproven and many have disputed this claim, including the Kaganovich family, who deny that Rosa and Stalin ever met.

Stalin's mother died in 1937; he did not attend the funeral but instead sent a wreath.

In March 2001, Russian Independent Television NTV discovered a previously unknown grandson living in Novokuznetsk. Yuri Davydov told NTV that his father had told him of his lineage, but, because the campaign against Stalin's cult of personality was in full swing at the time, he was told to keep quiet. The Soviet dissident writer, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, had mentioned a son being born to Stalin and his common-law wife, Lida, in 1918 during Stalin's exile in northern Siberia.

Rise to power

In 1912 Stalin was assigned to the Bolshevik Central Committee at the Prague Party Conference. In 1917 Stalin was editor of Pravda, the official Communist newspaper, while Lenin and much of the Bolshevik leadership were in exile.

Following the February Revolution, Stalin and the editorial board took a position in favor of supporting Alexander Kerensky's provisional government and, it is alleged, went to the extent of declining to publish Lenin's articles arguing for the provisional government to be overthrown.

In April 1917, Stalin was elected to the Central Committee with the third highest vote total in the party and was subsequently elected to the Politburo of the Central Committee (May 1917); he held this position for the remainder of his life.

According to certain accounts, Stalin only played a minor role in the Revolution of 1917. However, the distinguished Harvard professor Adam Ulam argues that each man in the Central Committee had a specific assignment. Upon his return to Russia in July 1917 Lenin argued that a great opportunity existed to seize power from the Kerensky government, merely by arresting its members. Party leadership did its best to organize and coordinate each key leader's role in such a way as to assure the success of the October Revolution. However, Stalin's role may have been less central to the effort than the role taken by others such as Trotsky.

The following summary of Trotsky's Role in 1917 was given by Stalin in Pravda, November 6, 1918:

All practical work in connection with the organization of the uprising was done under the immediate direction of Comrade Trotsky, the President of the Petrograd Soviet. It can be stated with certainty that the Party is indebted primarily and principally to Comrade Trotsky for the rapid going over of the garrison to the side of the Soviet and the efficient manner in which the work of the Military Revolutionary Committee was organized.[9]

Later, in 1924, Stalin himself created a myth around a so-called "Party Centre" which "directed" all practical work pertaining to the uprising, consisting of himself, Yakov Sverdlov, Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky, Moisei Uritsky, and Andrei Bubnov. However, no evidence was ever shown for the activity of this "centre," which would, in any case, have been subordinate to the Military Revolutionary Council, headed by Trotsky.

During the Russian Civil War and Polish-Soviet War, Stalin was a political commissar in the Red Army at various fronts. For some time he was in charge of defense of the town Tsaritsino, where he displayed a tendency toward strong measures and unjustified arrests. At some point Trotsky had to telegraph to Lenin requesting permission to remove Stalin from leadership because military efforts were going badly in spite of military superiority. At that time Stalin was recalled to Moscow. However, in spite of repeated requests from Trotsky to keep Stalin away from military affairs, Lenin did use him because of his ability to seek tasks to completion.

Stalin's first government position was as People's Commissar for Nationality Affairs (1917–1923). He was also People's Commissar of the Workers and Peasants Inspection (1919–1922), a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic (1920–1923) and a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Congress of Soviets (from 1917).

Campaign against the Left and Right Opposition

On April 3, 1922, Stalin was made general secretary of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), a post that he subsequently built up into the most powerful in the country by using it to cultivate supporters. It has been claimed that he initially attempted to decline the post, but was refused. This position was seen to be of a technical nature, a minor one within the party (Stalin was sometimes referred to as "Comrade Card-Index" by fellow party members) but actually had potential as a power base as it allowed Stalin to fill middle echelon positions of the party with his allies. As a result, in collective voting, Stalin's position on any issue became decisive.

As Stalin's popularity grew within the Bolshevik party he gained plenty of political power. This took the dying Lenin by surprise - their relationship had deteriorated over time and in his last Testament Lenin famously called for the removal of the "rude," "disloyal" and "capricious" Stalin. However, this document was voted on for adoption by the Party in a Congress resulting in a unanimous vote against endorsing Lenin's position because he was deemed by this time to be very ill.

After Lenin's death in January 1924, Stalin, Lev Borisovich Kamenev, and Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev together governed the party, placing themselves ideologically between Trotsky (on the left wing of the party) and Nikolay Ivanovich Bukharin (on the right). During this period, Stalin abandoned the traditional Bolshevik emphasis on international revolution in favor of a policy of building "Socialism in One Country," in contrast to Trotsky's theory of Permanent Revolution. Stalin argued that the Soviet Union lacked the military and economic power to pursue revolution elsewhere and argued that such a policy would only create enemies for the Soviets and lead to the destabilization of the U.S.S.R.

In the struggle for leadership it was evident that whoever assumed power had to be viewed as loyal to Lenin and to Lenin's principles. Stalin organized Lenin's funeral and made a speech professing undying loyalty to Lenin, in almost religious terms.[10] He undermined Trotsky, who was sick at the time, possibly by misleading him about the date of the funeral. Thus although Trotsky was Lenin’s associate throughout the early days of the Soviet regime, he lost ground to Stalin. Stalin made great play of the fact that Trotsky had joined the Bolsheviks just before the revolution, and publicized Trotsky's pre-revolutionary disagreements with Lenin. Another event that helped Stalin's rise was the fact that Trotsky came out against publication of Lenin's Testament in which he pointed out the strengths and weaknesses of Stalin and Trotsky and the other main players, and suggested that he be succeeded by a small group of people.

An important feature of Stalin’s rise to power was his skill in manipulating his opponents and playing them off against each other. Stalin formed a "troika" of himself, Zinoviev, and Kamenev against Trotsky. When Trotsky had been eliminated Stalin then joined Bukharin and Rykov against Zinoviev and Kamenev, emphasizing their vote against the insurrection in 1917. Zinoviev and Kamenev then turned to Lenin's widow, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya; they formed the "United Opposition" in July 1926.

In 1927 during the 15th Party Congress Trotsky and Zinoviev were expelled from the party and Kamenev lost his seat on the Central Committee. Stalin soon turned against the "Right Opposition," represented by his erstwhile allies, Bukharin and Rykov.

Stalin gained popular appeal through portraying himself as a 'man of the people,' with his roots in the humblest social class. The Russian people had tired from the world war and the civil war, and Stalin's policy of concentrating on building "Socialism in One Country" was viewed as a practical antidote to war (compared to Trotsky's calls for Permanent Revolution)

Stalin took great advantage of a ban on factionalism. This ban prohibited any group from openly opposing the policies of the leader of the party because that would constitute a de facto opposition. By 1928 (the first year of the institution of the Five-Year Plans for economic development) Stalin was supreme among the leadership, and the following year Trotsky was exiled because of his opposition to Stalin. Having also outmaneuvered Bukharin's Right Opposition and now advocating collectivization and industrialization, Stalin succeeded in exerting control over the party and the country.

However, as the popularity of other leaders such as Sergei Kirov and the so-called Ryutin Affair were to demonstrate, Stalin did not achieve absolute power until the Great Purge of 1936–1938.

Stalin's secret police and espionage activities

No reference to Joseph Stalin can be made without reference to his unmatched ability to use his intelligence services and the secret police. Though the Soviet secret police, the Cheka (later, the State Political Directorate GPU and OGPU), had already evolved into an arm of state-sanctioned murder under Lenin, Stalin took the use of such forces to a new level in order to solidify his hold on power and eliminate all enemies, real or perceived.

Stalin also vastly increased the foreign espionage activities of Soviet secret police and foreign intelligence. Under his guiding hand, Soviet intelligence forces began to set up intelligence networks in most of the major nations of the world, including Germany (the famous Rote Kappelle spy ring), Great Britain, France, Japan, and the United States. Stalin saw no difference between espionage, communist political propaganda actions, and state-sanctioned violence, and he began to integrate all of these activities within the NKVD, which preceded the KGB. Stalin made considerable use of the Communist International movement in order to infiltrate agents and to ensure that foreign Communist parties remained pro-Soviet and pro-Stalin.

One of the best early examples of Stalin's ability to integrate secret police and foreign espionage came in 1940, when he gave approval to the secret police to have Leon Trotsky assassinated in Mexico.

Stalin and changes in Soviet society

Industrialization

The Russian Civil War and wartime communism had a devastating effect on the country's economy. Industrial output in 1922 was 13 percent of that in 1914. A recovery followed under Lenin's New Economic Policy, which allowed a degree of market flexibility within the context of socialism.

Under Stalin's direction, this was replaced by a system of centrally ordained "Five-Year Plans" in the late 1920s. These called for highly ambitious state-guided "crash" industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture.

With no seed capital, little international trade, and virtually no modern infrastructure, Stalin's government financed industrialization by both restraining consumption on the part of ordinary Soviet citizens, to ensure that capital went for re-investment into industry, and by ruthless extraction of wealth from the kulaks.

In 1933, worker's real earnings sank to about one-tenth of the 1926 level. There was also use of the unpaid labor of both common and political prisoners in labor camps and the frequent "mobilization" of communists and Komsomol members for various construction projects. The Soviet Union also made use of foreign experts, e.g. British engineer Stephen Adams, to instruct their workers and improve their manufacturing processes.

In spite of early breakdowns and failures, the first two Five-Year Plans achieved rapid industrialization from a very low economic base. While there is general agreement among historians that the Soviet Union achieved significant levels of economic growth under Stalin, the precise rate of this growth is disputed.

Official Soviet estimates placed it at 13.9 percent, Russian and Western estimates gave lower figures of 5.8 percent and even 2.9 percent. Indeed, one estimate is that Soviet growth temporarily was much higher after Stalin's death.[11]

Collectivization

Stalin's regime moved to force collectivization of agriculture. This was intended to increase agricultural output from large-scale mechanized farms created through integration of smaller private farms. It was also meant to bring the peasantry under more direct political control and to facilitate the collection of taxes. Collectivization meant drastic social changes, on a scale not seen since the abolition of serfdom in 1861, and alienation of peasants from control of the land and its produce. Essentially, collectivization represented a forced shift from private property in the realm of agriculture to collective, state control. Practical implementation of this idea was a violent breach of democratic norms. The object of the collectivization was not only land, but farming equipment, livestock, produce and even peasants' homes. Collectivization led to a drastic drop in living standards for many peasants, and caused violent reactions by the peasantry that was heavily suppressed by Red Army.

In the first years of collectivization, it was estimated that industrial and agricultural production would rise by 200 percent and 50 percent respectively,[12] however, agricultural production actually dropped. Stalin blamed this unanticipated failure on kulaks (rich peasants), who resisted collectivization. (However, kulaks only made up 4 percent of the peasant population; the "kulaks" that Stalin targeted included the moderate middle peasants who took the brunt of violence from the State Political Directorate (OGPU) and the Komsomol. The middle peasants were about 60 percent of the population). Therefore those defined as "kulaks," "kulak helpers," and later "ex-kulaks" were ordered by Stalin to be shot, placed into Gulag labor camps, or deported to remote areas of the country, depending on the charge.

The two-stage progress of collectivization—interrupted for a year by Stalin's famous editorial, "Dizzy with success"[13] and "Reply to Collective Farm Comrades" [14] —is a prime example of Stalin's capacity for tactical political withdrawal followed by intensification of initial strategies.

Many historians assert that the disruption caused by collectivization was largely responsible for major famines. (Chairman Mao Zedong of China would trigger a similar famine in 1959 to 1961 with his Great Leap Forward).

During the 1932–1933 famine in Ukraine and the Kuban region, now often known in Ukraine as the Holodomor, not only "kulaks" were killed or imprisoned. Stephane Courtois' Black Book of Communism and other sources document that all grain was taken from areas that did not meet targets. This even included the next year's seed grain. Peasants were, nevertheless, forced to remain in these starving areas. Sales of train tickets were halted and the Political Directorate of the State created barriers and obstacles to prevent people from fleeing the starving areas.

However, famine also affected various other parts of the USSR. The death toll from famine in the Soviet Union at this time is estimated at between five and ten million people. Such figures are difficult to square with population figures for the period (which are accepted in the West) that show the population increasing from 147 million in 1926 to 164 million in 1937 although figures such as Robert Conquest of the Hoover Institution has written on the famine in great detail. During this same period the Soviet Union was exporting grain.

Soviet authorities and other historians have argued that tough measures and the rapid collectivization of agriculture were necessary in order to achieve an equally rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union and ultimately win World War II. This is disputed by other historians such as Alexander Nove, who claim that the Soviet Union industrialized in spite of, rather than thanks to, its collectivized agriculture.

Science

Science in the Soviet Union was under strict ideological control, along with art and literature. In the Soviet Union, Marxism-Leninism was truly the "Queen of the Sciences," especially during Stalin's rule. On the positive side, there was significant progress in "ideologically safe" domains, owing to the free Soviet education system and state-financed research. However, in several cases the consequences of ideological pressure were dramatic—the most notable examples being attacks on the "bourgeois pseudosciences" of genetics and cybernetics.

In the late 1940s there were also attempts to suppress special and general relativity, as well as quantum mechanics, on grounds of them being allegedly rooted in idealism rather than materialism. But the chief Soviet physicists made it clear that without using these theories, they would be unable to create a nuclear bomb. Hundreds of scientists were purged, mainly through the efforts of Trofim Lysenko, Stalin's favorite "scientist," who developed proof that Lamarck's evolutionary views (which supported Marxism's understanding of natural development) rather than Darwin's were most accurate.

Linguistics was one area of Soviet academic thought to which Stalin personally and directly contributed. At the beginning of Stalin's rule, the dominant figure in Soviet linguistics was Nikolai Yakovlevich Marr, who argued that language is a class construction and that language structure is determined by the economic structure of society. Stalin, who had previously written about language policy as People's Commissar for Nationalities, felt he grasped enough of the underlying issues to coherently oppose this simplistic Marxist formalism, ending Marr's ideological dominance over Soviet linguistics. Stalin's principal work discussing linguistics is a small essay, "Marxism and Linguistic Questions."[15]

Although no great theoretical contributions or insights came from it, neither were there any apparent errors in Stalin's understanding of linguistics; his influence arguably relieved Soviet linguistics from the sort of ideologically driven theory that could have dominated this arena.

It should be recognized, nevertheless, that much progress was made under Stalin in some areas of science and technology. His leadership laid the groundwork for the famous achievements of Soviet science in the 1950s, such as the development of the BESM-1 computer in 1953 and the launching of Sputnik in 1957.

Indeed, many politicians in the United States expressed a fear, after the "Sputnik crisis," that their country had been eclipsed by the Soviet Union in science and in public education.

Social services

The Soviet people also benefited from a great degree of social liberalization. As never before, females were given equal education opportunities and women had equal rights in employment that contributed to improving lives for women and families. Women began to occupy leadership roles in industry and education. To assist them, state wide daycare systems were gradually developed. Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which vastly increased the lifespan for the typical Soviet citizen and the quality of life. Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people universal access to health care and education, effectively creating the first generation free from the fear of typhus, cholera, and malaria. The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record-low numbers, increasing life spans by decades.

Soviet women under Stalin were also the first generation in Russia to give birth in a hospital, with access to prenatal care. Education also improved as the economic development of the U.S.S.R. continued under Stalin. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first generation where almost was literate. The social program "LicBez" (from Russian 'Licvidatsiya Bezgramotnosti' for 'elimination of illiteracy') was devised to eliminate illiteracy. The Soviet regime required each child had to attend school (four years in the beginning, then progressively eight and later ten years of required formal schooling) free of charge. This was also made available to Civil War, and later World War II orphans.

This represented the first time in Russian history that a coordinated effort was made to improve orphans' lives by providing basic care and professional education. Publicity campaigns were developed to encourage young men and women to study engineering as preparation for a career in engineering in various industries relating to chemistry, metallurgy and aviation. Engineers were sent abroad to study modern industrial technology and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract. Transportation systems were also improved, as many new railways and roads were constructed. Workers who exceeded their quotas, Stakhanovites, were rewarded with incentives for their efforts. They were thus in a better position to purchase goods in the expanding Soviet economy.

With industrialization and due to the heavy human losses resulting from World War II as well as the repression and genocide suffered by the generation that lived under Stalin, a manpower shortage resulted that especially opened up new job opportunities for women.

Culture and religion

During Stalin's reign the official and long-lived style of Socialist Realism was established for painting, sculpture, music, drama and literature. Previously fashionable "revolutionary" expressionism, abstract art, and avant-garde experimentation were discouraged or denounced as "formalism." Careers were made and broken, some more than once. Famous figures were not only repressed, but often persecuted, tortured and executed, both "revolutionaries" (among them Isaac Babel, Vsevolod Meyerhold) and "non-conformists" (for example, Osip Mandelstam).

A minority, both representing the "Soviet man" (Arkady Gaidar) and remnants of the older pre-revolutionary Russia (Konstantin Stanislavski), thrived. A number of former émigrés returned to the Soviet Union, among them Alexei Tolstoi in 1925, Alexander Kuprin in 1936, and Alexander Vertinsky in 1943.

Poet Anna Akhmatova was subjected to several cycles of suppression and rehabilitation, but was never herself arrested. Her first husband, poet Nikolai Gumilev, had been shot in 1921, and her son, historian Lev Gumilev, spent two decades in the gulag.

The degree of Stalin's personal involvement in general and specific developments has been assessed variously. His name, however, was constantly invoked during his reign in discussions of culture as in just about everything else. In several famous court cases, his opinion sealed the fate of the defendants.

Stalin's occasional beneficence showed itself in strange ways. For example, Mikhail Bulgakov was driven to poverty and despair; yet, after a personal appeal to Stalin, he was allowed to continue working. His play, The Days of the Turbins, with its sympathetic treatment of an anti-Bolshevik family caught up in the Civil War, was finally staged, apparently also on Stalin's intervention, and began a decades-long uninterrupted run at the Moscow Arts Theater.

Some insights into Stalin's political and aesthetic thinking might perhaps be gleaned by reading his favorite novel, Pharaoh, by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus, a historical novel on mechanisms of political power. Similarities have been pointed out between this novel and Sergei Eisenstein's film, Ivan the Terrible, produced under Stalin's tutelage.

In architecture, a Stalinist Empire Style (basically, updated neoclassicism on a very large scale, exemplified by the seven skyscrapers of Moscow) replaced the constructivism of the 1920s.

An amusing anecdote has it that the Moskva Hotel in Moscow was built with mismatched side wings because Stalin had mistakenly signed off on both of the two proposals submitted, and the architects had been too afraid to clarify the matter. In actuality the hotel had been built by two independent teams of architects that had differing visions of how the hotel should look.

Stalin's role in the fortunes of the Russian Orthodox Church is complex. Continuous persecution in the 1930s resulted in its near-extinction: by 1939, active parishes numbered in the low hundreds (down from 54,000 in 1917), many churches had been leveled or used as clubs, offices, storage space, or as museums. Ceremonial artifacts and vessels were confiscated. Religious icons were burned. Tens of thousands of priests and other religious leaders were persecuted. Many nuns were said to have been raped. During World War II, however, the Church was allowed a revival (winter 1941-1942) as a patriotic organization, after the NKVD had recruited the new metropolitan, the first after the revolution, as a secret agent. Thousands of parishes were reactivated, until a further round of suppression took place during Khrushchev's rule.

The Russian Orthodox Church Synod's recognition of the Soviet government and of Stalin personally led to a schism with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia that remains not fully healed to the present day.

Stalin's rule had a largely disruptive effect on the numerous indigenous cultures that made up the Soviet Union. The politics of the Korenization ("enrootment") and forced development of "Cultures National by Form, Socialist by their substance" allowed minorities to survive and integrate into Russian society at some cost to their identity.

The attempted unification of cultures in Stalin's later period was very harmful. Political repressions and purges had even more devastating repercussions on the indigenous cultures than on urban ones, since the cultural elite of the indigenous culture was often small. The traditional lives of many peoples in the Siberian, Central Asian and Caucasian provinces was upset and large populations were displaced and scattered in order to pre-empt nationalist uprisings.

Many religions popular in the ethnic regions of the Soviet Union including the Roman Catholic Church, Uniats, Baptists, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, etc. underwent ordeals similar to the Orthodox churches. Thousands of clergy were persecuted, and hundreds of churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, sacred monuments, monasteries and other religious buildings were razed.

Purges and deportations

The purges

As head of the Politburo, Stalin consolidated near-absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party, justified as an attempt to expel 'opportunists' and 'counter-revolutionary infiltrators'. Those targeted by the purge were often expelled from the party, however more severe measures ranged from banishment to the Gulag labor camps and to execution after trials held by NKVD operatives.

The Purges commenced after the assassination of Sergei Kirov, the popular leader of the party in Leningrad. Kirov was very close and loyal to Stalin and his assassination sent chills through the Bolshevik party. It is disputed among historians whether Kirov's assassination was masterminded by Stalin due to Kirov's growing popularity. Stalin took advantage of the Kirov assassination to begin tightening security, (and in effect to remove those who might have threatened Stalin's leadership). He initiated efforts aimed at identifying alleged spies and counter-revolutionaries.

Most notably in the case of alleged Nazi collaborator Tukhachevsky, many military leaders were convicted of treason. The shakeup in command may have cost the Soviet Union dearly during the German invasion of 22 June, 1941, and its aftermath. Stalin's Show Trials also saw the execution of key Soviet leaders who had been with Lenin from the start including Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin and Trotsky.

The repression of many high-ranking revolutionaries and party members led Leon Trotsky to claim that a "river of blood" separated Stalin's regime from that of Lenin. Solzhenitsyn alleges that Stalin drew inspiration from Lenin's regime with the presence of labor camps and the executions of political opponents that occurred during the Russian Civil War. Trotsky's August 1940 assassination in Mexico, where he had lived in exile since January 1937, eliminated the last of Stalin's opponents among the former, pre-revolution seniority Party leadership. Only three members of the "Old Bolsheviks" (Lenin's Politburo) now remained—Stalin himself, "the all-Union Chieftain" Mikhail Kalinin, and Premier Vyacheslav Molotov.

No segment of society was left untouched during the purges. Article 58 of the legal code, listing prohibited "anti-Soviet activities," was interpreted and applied in the broadest manner. Initially, the execution lists for the enemies of the people were confirmed by the Politburo.

Over time the procedure was greatly simplified and delegated down the line of command. People would inform on others arbitrarily, to attempt to redeem themselves, out of envy and plain dislike, or to gain some retributions or benefits. A worker would report on his boss, son on his father, and a young man on his brother. The flimsiest pretexts were often enough to brand someone an "Enemy of the People," starting the cycle of public persecution and abuse, often proceeding to interrogation, torture and deportation, if not death. Nadezhda Mandelstam, the widow of the poet Osip Mandelstam and one of the key memoirists of the Purges, recalls being shouted at by Akhmatova: "Don't you understand? They are arresting people for nothing now?" The Russian word troika - initially a sledge driven by the power of three horses - gained a new meaning: a quick, simplified trial by a committee of three subordinated to the NKVD. Often perpetrators of the purges - NKVD staff - used it as an opportunity for promotion, to enrich themselves, settle old grudges etc. Since entire families were swept away, women often became object of sexual abuse during interrogation process and in labor camps.

Towards the end of the purge, the Politburo relieved NKVD head Nikolai Yezhov, from his position for overzealousness. He was subsequently executed. Some historians such as Amy Knight and Robert Conquest postulate that Stalin had Yezhov and his predecessor, Genrikh Yagoda, removed in order to deflect blame from himself.

In parallel with the purges, efforts were made to rewrite the history in Soviet textbooks and other propaganda materials. Notable people executed by NKVD were removed from the texts and photographs as though they never existed. Gradually, the history of revolution was transformed to a story about just two key characters: Lenin and Stalin.[16]

Deportations

Shortly before, during and immediately after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations on a huge scale which profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union.

Over 1.5 million people were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian republics. Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the official reasons for the deportations. Many non-Russian ethnic groups were deported completely or partially. Stalin's Russification policies were similar to those of the Tsars. Stalin has been called the 'Red Tsar'.

In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninist principles, and reversed most of them, although it was not until as late as 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhs and Volga Germans were allowed to return en masse to their homelands. The deportations had a profound effect on the peoples of the Soviet Union. The memory of the deportations played a major part in the separatist movements in the Baltic States, Tatarstan and Chechnya, even today.

Numbers of victims

Early researchers of the number killed by Stalin's regime were forced to rely largely upon anecdotal evidence, and their estimates range as high as 60 million.[17][18] After 1991, hard evidence from the Soviet archives finally became available, and such estimates became more difficult to sustain. The archives record that about 800,000 prisoners were executed (for either political or criminal offenses) under Stalin, while another 1.7 million died of privation or "other causes" in the Gulags and some 389,000 perished during kulak resettlement - a total of about three million victims.

Debate continues however,[19] since some historians believe the archival figures are unreliable.[20] It is generally agreed that the data are incomplete, since some categories of victim were carelessly recorded by the Soviets - such as the victims of ethnic deportations, or of German population transfer in the aftermath of World War II.

These numbers are by no means the full story of deaths attributable to the regime however, since at least another 6 to 8 million victims of the 1932-1933 famine must be added. Again, historians differ, this time as to whether or not the famine victims were purposive killings - as part of the campaign of repression against kulaks - or whether they were simply unintended victims of the struggle over forced collectivization.

It appears that a minimum of ten million deaths (four million by repression and six million from famine) are attributable to the regime, with a number of recent books suggesting a probable figure of somewhere between 15 to 20 million. Adding 6-8 million famine victims to Erlikman's estimates above, for example, would yield a figure of between 15 and 17 million victims. Robert Conquest[21] meanwhile, has revised his original estimate of up to 30 million victims down to 20 million. Others, however, continue to maintain that their earlier (much higher) estimates are correct.[22]

World War II

After the failure of Soviet and Franco-British talks on a mutual defense pact in Moscow, Stalin realized that war with Germany was inevitable and negotiated a non-aggression pact with Germany. In his speech on August 19, 1939, Stalin prepared his comrades for the great turn in Soviet policy, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany. According to a controversial Russian emigre specializing in Soviet military history, Viktor Suvorov, Stalin expressed in the speech an expectation that the war would be the best opportunity to weaken both the Western nations and Nazi Germany, and make Germany suitable for "Sovietization." Whether this speech was ever delivered to the public and what its content was is still debated.

Officially a non-aggression treaty only, the Pact had a "secret" annex according to which Central Europe was divided into the two powers' respective spheres of influence. The USSR was promised an eastern part of Poland, primarily populated with Ukrainians and Belorussians in case of its dissolution, as long as Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland were recognized as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence. Another clause of the treaty was that Bessarabia, then part of Romania, was to be joined to the Moldovan ASSR, and become the Moldovan SSR under control of Moscow.

Both Stalin and Hitler intended to outwit each other. While Wermacht and Red Army had joined small scale tactical exercise and maneuvers, Stalin tried to get some time to prepare Red Army and raise new leadership, and Hitler wanted to free his hands for Europe and delude Stalin. While Russia was sending trainloads of provision, nonferrous metals and other important raw materials to Germany, Germany was developing Operation Barbarossa.

On September 1, 1939, the German invasion of Poland started World War II. Stalin then decided to intervene, and on September 17 the Red Army entered eastern Poland and the Baltic states and annexed these territories.

In November 1939, Stalin sent troops over the Finnish border provoking war. The Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland proved to be more difficult than Stalin and the Red Army were prepared for, and the Soviets sustained high casualties. The Soviets prevailed in March, 1940, but the problems of the Soviet army had been revealed to the rest of the world, including Germany.

On March 5, 1940, the Soviet leadership approved an order of execution for more than 25,700 Polish "nationalist, educators and counterrevolutionary" activists in the parts of the Ukraine and Belarus republics that had been annexed from Poland. This event has become known as the Katyn Massacre. Official Soviet archive records, opened in 1990 when glasnost was still in vogue, show that Stalin had every intention of treating the Poles as political prisoners. [23] Treating the executed as Prisoners of War would require prosecution for the surviving perpetrators of the crime; so the matter was dropped.

In June 1941, Hitler broke the pact with Stalin and, after reaching an impasse with Britain, opened a second front (Operation Barbarossa) and invaded the Soviet Union. Although expecting an eventual war with Germany, Stalin was unprepared for this invasion when it occurred. Even though Stalin received intelligence warnings of a German attack,[24] he sought to avoid any obvious defensive preparation which might further provoke the Germans, in the hope of buying time to modernize and strengthen his military forces. In the initial hours after the German attack commenced, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.[25]

The Germans initially made huge advances, capturing and killing millions of Soviet troops. The Soviet Red Army put up fierce resistance during the war's early stages, but they were plagued by an ineffective defense doctrine against the better-equipped, well-trained and experienced German forces. Hitler's experts had expected eight weeks of war, and early indications appeared to support their predictions. However, the invading German forces were eventually driven back in December 1941 near Moscow.

Stalin met in several conferences with Churchill and/or Roosevelt in Moscow, Tehran, and Yalta, to plan military strategy; (Truman taking the place of the deceased Roosevelt).

In these conferences, his first appearances on the world stage, Stalin proved to be a formidable negotiator. Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Secretary noted:

"Marshal Stalin as a negotiator was the toughest proposition of all. Indeed, after something like thirty years' experience of international conferences of one kind and another, if I had to pick a team for going into a conference room, Stalin would be my first choice. Of course the man was ruthless and of course he knew his purpose. He never wasted a word. He never stormed, he was seldom even irritated."[26]

His shortcomings as strategist are frequently noted regarding the massive Soviet loss of life and early Soviet defeats. An example is the summer offensive of 1942, which led to even more losses by the Red Army and recapture of initiative by the Germans. Stalin eventually recognized his lack of know-how and relied on his professional generals to conduct the war. Unfortunately during his purge, Stalin had eliminated thousands of Soviet military officers.

Yet Stalin did rapidly relocate Soviet industrial production east of the Volga River, far from Luftwaffe-reach, to sustain the Red Army's war machine with astonishing success. Additionally, Stalin was well aware that other European armies had utterly disintegrated when faced with Nazi military efficacy. Stalin responded effectively by subjecting his army to galvanizing terror and unrevolutionary, nationalist appeals to patriotism. He even appealed to the Russian Orthodox Church and invoked the national Russian heroes of the past. On November 6, 1941, Stalin addressed the whole nation of the Soviet Union for the second time (the first time was earlier that year on July 2).

According to Stalin's Order No. 227 of July 27, 1942, any commander or commissar of a regiment, battalion or army, who allowed retreat without permission from above was subject to military tribunal. The Soviet soldiers who surrendered were declared traitors; however most of those who survived the brutality of German captivity were mobilized again as they were freed. Between 5 and 10 percent of them were sent to gulags.

In the war's opening stages, the retreating Red Army also sought to deny resources to the enemy through a "scorched earth" policy of destroying the infrastructure and food supplies of areas before the Germans could seize them. Unfortunately, this, along with abuse by German troops, caused inconceivable starvation and suffering for the civilian population that was left behind.

According to recent figures, of an estimated four millions Prisoners of War taken by the Russians, (including Germans, Japanese, Hungarians, Romanians and others), some 580,000 never returned, presumably victims of privation or the Gulags. Returning Soviet soldiers who had surrendered were viewed with suspicion and some were killed [17] compared with 3.5 million Soviet POW that died in German camps. [27]

The Soviet Union suffered the second highest number of civilian losses (20 million) and the highest number of military losses (at least 8,668,400 Red Army personnel) in World War II. The Nazis considered Slavs to be "sub-human," and many people believe the Nazis killed Slavs as an ethnically targeted genocide. This concept of Slavic inferiority was also the reason why Hitler did not accept into his army many Soviet citizens who wanted to fight the regime until 1944, when the war was lost for Germany.

In the Soviet Union, World War II left a huge deficit of men of the wartime fighting-age generation. To this day the war is remembered very vividly in Russia, Belarus, and other parts of the former Soviet Union as the "Great Patriotic War," and May 9, "Victory Day," is one of Russia's biggest national holidays.

Post-war era

Domestically, Stalin was presented as a great wartime leader who had led the Soviets to victory against the Nazis. By the end of the 1940s, Russian nationalism increased. For instance, some inventions and scientific discoveries were reclaimed by ethnic Russian researchers. Internationally, Stalin viewed Soviet consolidation of power as a necessary step to protect the USSR by surrounding it with countries with friendly governments, to act as a cordon sanitaire (buffer) against possible invaders (while the West sought a similar buffer against communism).

He had hoped that American withdrawal and demobilization would lead to increased communist influence, especially in Europe. Each side might view the other's defensive actions as destabilizing provocations and these security dilemmas frayed relations between the Soviet Union and its former World War II western allies and led to a prolonged period of tension and distrust between East and West known as the Cold War.

The Red Army ended World War II occupying much of the territory that had been formerly held by the Axis countries:

In Asia, the Red Army had overrun Manchuria in the last month of the war and then also occupied Korea above the 38th parallel north. Mao Zedong's Communist Party of China, though receptive to minimal Soviet support, defeated the pro-Western and heavily American-assisted Chinese Nationalist Party in the Chinese Civil War.

The Communists controlled mainland China while the Nationalists clung only to the island of Formosa (now Taiwan). The Soviet Union soon after recognized Mao's communist People's Republic of China, which it regarded as a new ally although Mao felt that he did not receive proper treatment or appreciation from Stalin when he visited the Soviet Union after he assumed control of the Chinese mainland.

Diplomatic relations reached a high point with the signing of the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance. Both communist states provided military support to a new communist state in North Korea, which invaded U.S.-allied South Korea in 1950 to start the Korean War. China was not pleased with Stalin's tacit support of North Korea's invasion of the South, fearing that it might destabilize his gains in China and possibly provoke an all-out invasion of the Mainland by the United States.

In Europe, there were Soviet occupation zones in Germany and Austria. Hungary and Poland were under practical military occupation. From 1946-1948 communist governments were imposed in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and home-grown communist dictatorships rose to power in Yugoslavia and Albania.

These nations became known as the "Communist Bloc." Britain and the United States supported the anti-communists in the Greek Civil War and suspected the Soviets of supporting the Greek communists although Stalin ended his support while his then ally, Yugoslavia's Josip Broz Tito, continued his support of the Greek communists. Albania remained an ally of the Soviet Union, but Yugoslavia broke with the USSR in 1948. Greece, Italy and France were under the strong influence of local communist parties, which were at the very least friendly towards Moscow.

Both Superpowers viewed Germany as key. Once again, Stalin's pathological investment in foreign intelligence and espionage bore fruit. Armed with intelligence from the British traitor Donald Duart Maclean and other British and American espionage agents, Stalin was well aware that the United States possessed neither a sufficient atomic bomb arsenal nor the production capacity needed to produce atomic weapons to destroy Soviet or Communist land forces either in Europe or the Far East. He therefore ordered a blockade of West Berlin, which was under British, French, and U.S. occupation, to force these powers into surrendering their occupation zones in the city. He also began extensively arming Kim Il Sung's North Korean army and air forces (with military equipment and advisors far in excess of that required for defensive purposes) in order to facilitate Kim's 1950 invasion of South Korea.

The Berlin Blockade failed due to the unexpected massive aerial resupply campaign carried out by the Western powers known as the Berlin Airlift. In 1949, Stalin conceded defeat and ended the blockade. After West Germany was formed by the union of the three Western occupation zones, the Soviets declared East Germany a separate country in 1949, ruled by the communists.

Stalin originally supported the creation of Israel in 1948. The USSR was one of the first nations to recognize the new country and saw the creation of Israel as a way to reduce the British presence in the Middle East. Golda Meir came to Moscow as the first Israeli Ambassador to the USSR that year. But Stalin later changed his mind and came out against Israel. Right before his death in June 1953 Stalin was planning an anti-Zionist and anti-Jewish campaign in the USSR and another blood purge of the government.

In Stalin's final year of life, one of his last major foreign policy initiatives was the 1952 Stalin Note for German reunification and Superpower disengagement from Central Europe, but Britain, France, and the United States viewed this with suspicion and rejected the offer.

Stalin as theorist

Stalin contributions to Communist (or, more specifically, Marxist-Leninist) theory included his emphasis on the need to establish a communist hegemony in one state prior to attempting to extend to other states. Another of Stalin's contributions was his "Marxism and the National Question," a work praised by Lenin. His "Trotskyism or Leninism," was a factor in the "liquidation of Trotskyism as an ideological trend" within the CPSU(B). Stalin also attempted to refine the scientific and philosophical underpinnings of dialectical and historical materialism and those refinements continued to appear in Soviet writings on Marxism-Leninism until the demise of the Soviet State.

Stalin's Collected Works (in 13 volumes) was released in 1949. A subsequent 16 volume American Edition appeared, in which one volume consisted of the book "History of the CPSU(B) Short Course," although when released in 1938 this book was credited to a commission of the Central Committee.[28]

Death

On March 1, 1953, after an all-night dinner with interior minister Lavrenty Beria and future premiers Georgi Malenkov, Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin collapsed in his room, having probably suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Officially, the cause of death was listed as a cerebral hemorrhage. His body was preserved in Lenin's Mausoleum until October 31, 1961, when his body was removed from the Mausoleum and buried next to the Kremlin walls as part of the process of de-Stalinization.

It has been suggested that Stalin was assassinated. The ex-Communist exile Avtorkhanov argued this point as early as 1975. The political memoirs of Vyacheslav Molotov, published in 1993, claimed that Beria had boasted to Molotov that he poisoned Stalin: "I took him out."

Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs that Beria had, immediately after the stroke, gone about "spewing hatred against [Stalin] and mocking him," and then, when Stalin showed signs of consciousness, dropped to his knees and kissed his hand. When Stalin fell unconscious again, Beria immediately stood and spat.

In 2003, a joint group of Russian and American historians announced their view that Stalin ingested warfarin, a powerful rat poison that inhibits coagulation of the blood and so predisposes the victim to hemorrhagic stroke (cerebral hemorrhage).

His demise arrived at a convenient time for Beria and others, who feared being swept away in yet another purge. It is believed that Stalin felt Beria's power was too great and threatened his own. Whether or not Beria or another usurper was directly responsible for his death, it is true that the Politburo did not summon medical attention for Stalin for more than a day after he was found.

Cult of Personality and Legacy

Under Stalin's rule the Soviet Union was transformed from an agricultural nation to a nuclear superpower but at the cost of millions of lives. The USSR's industrialization was moderately successful and with the help of the United States' provision of supplies under the Lend Lease Plan, the country was able to defend against and eventually defeat the Axis invasion in World War II, though at an enormous cost in human life. Other historians claim that the USSR was bound for industrialization, and that its speed along this course was not necessarily improved by Bolshevik influence. It has also been argued that Stalin should be held accountable for the initial military disasters and enormous human casualties during WWII, because Stalin eliminated many military officers during the purges, and especially the most senior ones, and that he rejected the massive amounts of intelligence warning of the German attack.[29]

Stalin's political, social and economic policies as well as his great negotiating skills and his intelligence network laid the foundations for the USSR's emergence as a superpower. The harshness with which he conducted Soviet affairs was subsequently repudiated by his successors in the Communist Party leadership, notably in the denunciation of Stalinism by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1956. In his "Secret Speech," On the Personality Cult and its Consequences, delivered to a closed session of the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev denounced Stalin for his cult of personality, and his regime for "violation of Leninist norms of legality."

Stalin's immediate successors, however, continued to follow the basic principles of Stalin's rule - the political monopoly of the Communist Party presiding over a command economy and a security service able to suppress dissent. The large-scale purges of Stalin's era were never repeated although political repression continued. This was seen by some as a perpetuation of the Stalinist legacy.

Notes

- ↑ Although there is an inconsistency among published sources about Stalin's year and date of birth, Iosif Dzhugashvili is listed in the records of the Uspensky Church in Gori, Georgia as born on December 18 (Old Style: December 6) 1878. This birth date is maintained in his School Leaving Certificate, his extensive tsarist Russia police file, a police arrest record from April 18, 1902 which gave his age as 23 years, and all other surviving pre-revolution documents. Stalin himself listed December 18, 1878 in a curriculum vitae as late as 1920, in his own handwriting. However after his coming to power in 1922, the date was changed to December 21, 1879 (December 9, Old Style), and that was the day his birthday was celebrated in the Soviet Union. Russian playwright Edvard Radzinsky argues in his book Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996, ISBN 0385473974), that he changed the year to 1879 to have a nation-wide birthday celebration of his 50th birthday. He could not do it in 1928 because his rule was not absolute enough.

- ↑ Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005, ISBN 0674016971).

- ↑ Mark Gould and Jo Revill, Luxury beckons for East End's house of history The Observer, October 24, 2004. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, The Right of Nations to Self-Determination February-May 1914. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Martin Amis, Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million (New York, NY: Vintage, 2003, ISBN 1400032202), 133.

- ↑ Adam Bruno Ulam, Stalin: The Man and His Era (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1989, ISBN 080707005X), 354.

- ↑ Svetlana Alliluyeva, Twenty Letters to a Friend (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1967, ISBN 0060100990), 103–105.

- ↑ Stuart Kahan, The Wolf of the Kremlin: The First Biography of L.M. Kaganovich, the Soviet Union's Architect of Fear (William Morrow & Co, 1987, ISBN 0688075290).

- ↑ Note: Although this passage was quoted in Stalin's book The October Revolution issued in 1924, it was expunged in Stalin's Works released in 1949. J. V. Stalin, The October Revolution and the Tactics of the Russian Communists marxists.org. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ J.V. Stalin, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1924/01/30.htm On The Death Of Lenin] Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Elizabeth Brainerd, Reassessing the Standard of Living in the Soviet Union: An Analysis Using Archival and Anthropometric Data Journal of Economic History 70(1) (2010): 83-117. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ History of Russia: The rise of Stalin History World. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Josef Stalin, Dizzy with success Pravda, March 2, 1930. RetrievedOctober 24, 2022

- ↑ Josef Stalin, Reply to Collective Farm Comrades Pravda, April 3, 1930. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ J.V. Stalin, Marxism and Problems of Linguistics Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (Tate, 2014, ISBN 978-1849762519).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Twentieth Century Hemoclysm Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956 (NY: HarperPerennial, 2002, ISBN 0060007761).

- ↑ Soviet Studies and other sources Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Anne Applebaum, Gulag : A History (New York, NY: Anchor, 2004, ISBN 1400034094).

- ↑ Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment (London: Hutchinson, 1990, ISBN 0091742935).

- ↑ Deka-Megamurders (regimes murdering more than ten million) Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Benjamin B. Fischer, The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field Studies in Intelligence Winter (1999-2000). Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, Stalin's Intelligence The New York Times, June 12, 2005. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (New York: Knopf Dist. by Random House, 2004, ISBN 1400042305).

- ↑ Anthony Eden, Memoirs: The Reckoning (London: Cassell, 1965).

- ↑ Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2004, ISBN 0393020304), 568-569.

- ↑ History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union marx2mao.com. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Alexander N. Yakovlev, A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia (Yale University Press, 2004, ISBN 0300103220).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alliluyeva, Svetlana. Twenty Letters to a Friend. (English ed.) New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1967. ISBN 0060100990

- Amis, Martin. Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million. New York, NY: Vintage, 2003. ISBN 1400032202

- Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: A History. New York, NY: Anchor, 2004. ISBN 1400034094

- Bullock, Alan. Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. London: Fontana Press, 1998. ISBN 0006863744

- Boterbloem, Kees. Life and Death under Stalin: Kalinin Province, 1945–1953. Ithaca, NY: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999. ISBN 0773518118

- Conquest, Robert. The Great Terror: A Reassessment. London: Hutchinson, 1990. ISBN 0091742935

- Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. London: Hutchinson, 1986. ISBN 0091637503

- Courtois, Stephane et al. Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, translated from the French by Jonathan Murphy. Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0674076087

- Deutscher, Isaac. Stalin: A Political Biography. (1966) reprint Kessinger Pub. 2007. ISBN 1432579002

- Eden, Anthony. Memoirs: The Reckoning. London: Cassell, 1965.

- Gill, Graeme J. Stalinism. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1998. ISBN 031217764X

- De Jonge, Alex. Stalin and the Shaping of the Soviet Union. New York, NY: William Morrow & Co., 1986. ISBN 0688047300

- Ilic, Melanie (ed.). Stalin's Terror Revisited. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1403947058

- Iremashvili, Ioseb. Stalin und die Tragödie Georgiens. Berlin: 1932. (in German)

- King, David. The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia. Tate, 2014. ISBN 978-1849762519

- Kuromiya, Hiroaki. Stalin. New York, NY: Pearson/Longman, 2005. ISBN 0582784794

- Laqueur, Walter. Stalin: The Glasnost Revelations. London: Unwin Hyman, 1990. ISBN 0044407696

- Mace, James E. "The Man-Made Famine of 1933 in Soviet Ukraine." 1–14 in Roman Serbyn and Bohdan Krawchenko (eds.) Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1986. ISBN 0920862438

- McDermott, Kevin. Stalin: Revolutionary in an Era of War. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 0333711211

- Medvedev, Roy A., and Zhores A. Medvedev. The Unknown Stalin: His Life, Death and Legacy, Translated by Ellen Dahrendorf. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2004. ISBN 1585675024

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag. Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. New York, NY: Knopf : Dist. by Random House, 2004. ISBN 1400042305

- Overy, Richard. Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2004. ISBN 0393020304

- Radzinsky, Edvard. Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, Translated by H.T. Willetts. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996. ISBN 0385473974.

- Rayfield, Donald. Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him. New York, NY: Random House, 2004. ISBN 0375506322

- Rummel, R.J. Death By Government. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1560001453

- Rummel, R.J. Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers, 1990. ISBN 1560008873

- Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005. ISBN 0674016971

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956. NY: HarperPerennial, 2002. ISBN 0060007761

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin as Revolutionary, 1879–1929; A Study in History and Personality. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1973. ISBN 039305487X

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928–1941. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1990. ISBN 039302881X

- Ulam, Adam Bruno. Stalin: The Man and His Era. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1989. ISBN 080707005X

- Yakovlev, Alexander N. A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 0300103220

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.