Sumerian Civilization

| Ancient Mesopotamia |

|---|

| Euphrates – Tigris |

| Assyriology |

| Cities / Empires |

| Sumer: Uruk – Ur – Eridu |

| Kish – Lagash – Nippur |

| Akkadian Empire: Akkad |

| Babylon – Isin – Susa |

| Assyria: Assur – Nineveh |

| Dur-Sharrukin – Nimrud |

| Babylonia – Chaldea |

| Elam – Amorites |

| Hurrians – Mitanni |

| Kassites – Urartu |

| Chronology |

| Kings of Sumer |

| Kings of Assyria |

| Kings of Babylon |

| Language |

| Cuneiform script |

| Sumerian – Akkadian |

| Elamite – Hurrian |

| Mythology |

| Enûma Elish |

| Gilgamesh – Marduk |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

Sumer (or Šumer) was one of the early civilizations of the Ancient Near East, located in the southern part of Mesopotamia (southeastern Iraq) from the time of the earliest records in the mid-fourth millennium B.C.E. until the rise of Babylonia in the late third millennium B.C.E. The term "Sumerian" applies to all speakers of the Sumerian language. Sumer together with Ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley Civilization is considered the first settled society in the world to have manifested all the features needed to qualify fully as a "civilization." The development of the City-state as an organized social and political settlement enabled art, commerce, writing, and architecture, including the building of Temples (ziggurats) to flourish.

The history of Sumeria dates back to the beginning of writing and also of law, which the Sumerians are credited with inventing.[1] and was essential for maintaining order within the City-states. City-states for centuries used variations of Sumerian Law, which established set penalties for particular offenses. This represents recognition that societies can not function without respect for life and property and shared values. More and more people became aware of belonging to the same world as a result of Sumeria's contribution to the human story. Treaties from Sumeria indicate a preference for trade and commerce.

Ethnonym

The term "Sumerian" is an exonym first applied by the Akkadians. The Sumerians called themselves "the black-headed people" (sag-gi-ga) and their land "land of the civilized lords" (ki-en-gir). The Akkadian word Shumer may represent this name in dialect, but we actually do not know why the Akkadians called the southern land Shumeru. Biblical Shinar, Egyptian Sngr and Hittite Šanhar(a) could be western variants of Šumer. [2]

Background

The Sumerians were a non-Semitic people and were at one time believed to have been invaders, as a number of linguists believed they could detect a substrate language beneath Sumerian. However, the archaeological record shows clear uninterrupted cultural continuity from the time of the Early Ubaid period (5200-4500 B.C.E. C-14, 6090-5429 B.C.E. calBC) settlements in southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerian people who settled here farmed the lands in this region that were made fertile by silt deposited by the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers.

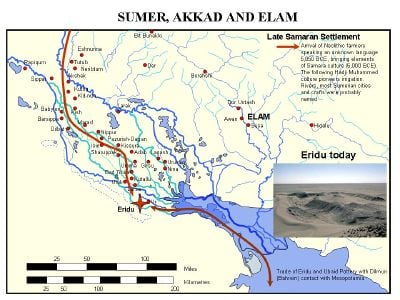

The challenge for any population attempting to dwell in Iraq's arid southern floodplain, where rainfall is currently less than 5 inches a year, was to manage the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to supply year-round water for farming and drinking. The Sumerian language has many terms for canals, dikes, and reservoirs. Sumerian speakers were farmers who moved down from the north after perfecting irrigation agriculture there. The Ubaid pottery of southern Mesopotamia has been connected via Choga Mami Transitional ware to the pottery of the Samarra period culture (c. 5700-4900 B.C.E. C-14, 6640-5816 B.C.E. in the north, who were the first to practice a primitive form of irrigation agriculture along the middle Tigris River and its tributaries. The connection is most clearly seen at Tell Awayli (Oueilli, Oueili) near Larsa, excavated by the French in the 1980s, where 8 levels yielded pre-Ubaid pottery resembling Samarran ware. Farming peoples spread down into southern Mesopotamia because they had developed a temple-centered social organization for mobilizing labor and technology for water control, enabling them to survive and prosper in a difficult environment.

City states

By the late fourth millennium B.C.E., Sumer was divided into about a dozen independent city-states, whose limits were defined by canals and boundary stones. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a priest (ensi) or king (lugal), who was intimately tied to the city's religious rites.

The principal Sumerian sites (from North to South) were the cities of:

- Mari—34°27′N 40°55′E

- Agade—33°06′N 44°06′E

- Kish (Tell Uheimir & Ingharra)—32°33′N 44°39′E

- Borsippa (Birs Nimrud)—32°23′30 N°44′20

- Nippur (Nuffar)—32°10′N 45°11′E

- Isin (Ishan al-Bahriyat)—31°56′N 45°17′E

- Adab (Tell Bismaya)—31°57′N 45°58′E

- Shuruppak (Fara)—31°46′N 45°30′E

- Girsu (Tello)—31°37′N 46°09′E

- Lagash (Al-Hiba)—31°26′N 46°32′E

- Bad-Tibira (Al Medina)—31°46′N 46°00′E

- Uruk (Warka)—31°18′N 45°40′E

- Larsa (Tell as-Senkereh)—31°14′N 45°51′E

- Ur (al Muqayyar)—30°57′45 N°46′06

- Eridu (Abu Shahrain)—30°48′57.02 N°45′59

minor cities:

- Sippar (Abu Habba)—33°03′N 44°18′E

- Kutha (Tell Ibrahim)—32°44′N 44°40′E

- Dilbat (Tell ed-Duleim)—32°09′N 44°30′E

- Marad ((Wanna es-) Sadun)—32°04′N 44°47′E

- Kisurra (Abu Hatab)—31°50′N 45°26′E

- Zabala (Tell Ibzeikh)—31°44′N 45°52′E

- Umma (Tell Jokha)—31°38′N 45°52′E

- Kisiga (Tell el-Lahm)—30°50′N 46°20′E

- Awan

- Hamazi

- Eshnunna

- Akshak

- Zimbir

Apart from Mari, which lies full 330 km northwest of Agade, but which is credited in the king list to have "exercised kingship" in the Early Dynastic II period, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad in what are now the Bābil, Wāsit, Dhi Qar, Al-Muthannā and Al-Qādisiyyah governorates of Iraq.

History

The Sumerian city states rise to power during the prehistorical Ubaid and Uruk periods. The historical record gradually opens with the Early Dynastic period from ca. the 29th century B.C.E., but remains scarce until the Lagash period begins in the 26th century. Classical Sumer ends with the Akkadian Empire in the 24th century. Following the Gutian period, there is a brief "Sumerian renaissance" in the 22nd century, cut short in ca. 2000 B.C.E. by Amorite invasions. The Amorite "dynasty of Isin" persists until ca. 1730 B.C.E. when Mesopotamia is united under Babylonian rule.

- Ubaid period 5300-3900 B.C.E.

- Uruk IV period 3900-3200 B.C.E.

- Uruk III period 3200-2900 B.C.E.

- Early Dynastic I period 2900-2800 B.C.E.

- Early Dynastic II period 2800-2600 B.C.E.

- Early Dynastic IIIa period 2600-2500 B.C.E.

- Early Dynastic IIIb period 2500-2334 B.C.E.

- Lagash dynasty period 2550-2380 B.C.E.

- Akkad dynasty period 2450-2250 B.C.E.

- Gutian period 2250-2150 B.C.E.

- Ur III period 2150-2000 B.C.E.

Ubaid period

A distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery spread throughout Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf region in the Ubaid period, when the ancient Sumerian religious center of Eridu was gradually surpassed in size by the nearby city of Uruk. The archaeological transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift from painted pottery domestically produced on a slow wheel, to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on fast wheels. The date of this transition, from Ubaid 4 to Early Uruk, is in dispute, but calibrated radiocarbon dates from Tell Awayli would place it as early as 4500 B.C.E.

Uruk period

By the time of the Uruk period (4500-3100 B.C.E. calibrated), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large temple-centered cities where centralized administrations employed specialized workers. It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labor (Subartu) captured from the hill country, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts. Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area - from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as Central Iran.

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists (like that found at Tell Brak), had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.

The end of the Uruk period coincided with the Priora oscillation, a dry period from c. 3200-2900 B.C.E. that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, called the Holocene climatic optimum. When the historical record opens, the Sumerians appear to be limited to southern Mesopotamia—although very early rulers such as Lugal-Anne-Mundu are indeed recorded as expanding to neighboring areas as far as the Mediterranean, Taurus and Zagros, and not long after legendary figures like Enmerkar and Gilgamesh, who are associated in mythology with the historical transfer of culture from Eridu to Uruk, were supposed to have reigned.

Early Dynastic

The ancient Sumerian king list recounts the early dynasties. Like many other archaic lists of rulers, it may include legendary names. The first king on the list whose name is known from any other source is Etana, 13th king of the first Dynasty of Kish. The first king authenticated through archaeological evidence is that of Enmebaragesi of Kish, the 22nd and penultimate king of that Dynasty, whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epic, and who may have been king at the time hegemony passed from Kish to Uruk once again. This has led to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself really was a historical king of Uruk.

Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty, took Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He is the last ethnically Sumerian king before the arrival of the Semitic named king, Sargon of Akkad.[3]

Lagash dynasty

The dynasty of Lagash is well known through important monuments, and one of the first empires in recorded history was that of Eannatum of Lagash, who annexed practically all of Sumer, including Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Larsa, and reduced to tribute the city-state of Umma, arch-rival of Lagash. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam and along the Persian Gulf. He seems to have used terror as a matter of policy - his stele of the vultures has been found, showing violent treatment of enemies.

Akkadian dynasty

The Semitic Akkadian language is first attested in proper names around 2800 B.C.E. From about 2500 B.C.E. one finds texts written entirely in Old Akkadian. The Old Akkadian language period was at its height during the rule of Sargon the Great (2350 - 2330), but most administrative tablets even during that period are still written in Sumerian, as that was the language used by the scribes. Gelb and Westenholz differentiate between three dialects of Old Akkadian - from the pre-Sargonic period, the period of rule by king Sargon and the city of Agade, and the Ur III period. Speakers of Akkadian and Sumerian coexisted for about one thousand years, from 2800 to 1800, at the end of which Sumerian ceased to be spoken. Thorkild Jacobsen has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre- and post-Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a "Semitic vs. Sumerian" conflict[4] However, it is certain that Akkadian was also briefly imposed on neighboring parts of Elam that were conquered by Sargon.

Gutian period

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of Gutians, another native Sumerian ruler, Gudea of Lagash, rose to local prominence, promoting artistic development and continuing the practices of the Sargonid kings' claims to divinity.

Sumerian renaissance

Later, the third dynasty of Ur under Ur-Nammu and Shulgi, whose power extended as far as northern Mesopotamia, was the last great "Sumerian renaissance," but already the region was becoming more Semitic than Sumerian, with the influx of waves of Martu (Amorites) who were later to found the Babylonian Empire. Sumerian, however, remained a sacerdotal language taught in schools, in the same way that Latin was used in the Medieval period, for as long as cuneiform was utilized.

Ecologically, the agricultural productivity of the Sumerian lands was being compromised as a result of rising salinity. The evaporation of irrigated waters left dissolved salts in the soil, making it increasingly difficult to sustain agriculture. There was a major depopulation of southern Mesopotamia, affecting many of the smaller sites, from about 2000 B.C.E., leading to the collapse of Sumerian culture.

Downfall

Following an Elamite invasion and sack of Ur during the rule of Ibbi-Sin (ca. 2004 B.C.E.), Sumer came under Amorite rule (taken to introduce the Middle Bronze Age). The independent Amorite states of the twentieth to eighteenth centuries are summarized as the "Dynasty of Isin" in the Sumerian king list, ending with the rise of Babylonia under Hammurabi in ca. 1730 B.C.E..

This period is generally taken to coincide with a major shift in population from southern Iraq toward the north, as a result of the increase in soil salinity. Soil salinity in this region had been long recognized as a major problem. Poorly drained irrigated soils, in an arid climate with high levels of evaporation, led to the deposit of crystalline salt in the soil, eventually reducing agricultural yields severely. During the Akkadian and Ur III phases, there was a shift from the cultivation of wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley, but this was insufficient, and during the period from 2100 B.C.E. to 1700 B.C.E., it is estimated that the population in this area declined by nearly three fifths [5]. This greatly weakened the balance of power within the region, weakening the areas where Sumerian was spoken, and comparatively strengthening those where Akkadian was the major language. Henceforth Sumerian would remain only a literate, sacerdotal or sacred language, similar to the position occupied by Latin in Middle Ages Europe.

Agriculture and hunting

The Sumerians adopted the agricultural mode of life which had been introduced into Lower Mesopotamia and practiced the same irrigation techniques as those used in Egypt.[6] Adams says that irrigation development was associated with urbanization [7], and that 89 percent of the population lived in the cities [8]

They grew barley, chickpeas, lentils, wheat, dates, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks and mustard. They also raised cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. They used oxen as their primary beasts of burden and donkeys or equids as their primary transport animal. Sumerians caught many fish and hunted fowl and gazelle.

Sumerian agriculture depended heavily on irrigation. The irrigation was accomplished by the use of shadufs, canals, channels, dikes, weirs, and reservoirs. The frequent violent floods of the Tigris, and less so, of the Euphrates, meant that canals required frequent repair and continual removal of silt, and survey markers and boundary stones continually replaced. The government required individuals to work on the canals in a corvee, although the rich were able to exempt themselves.

After the flood season and after the Spring Equinox and the Akitu or New Year Festival, using the canals, farmers would flood their fields and then drain the water. Next they let oxen stomp the ground and kill weeds. They then dragged the fields with pickaxes. After drying, they plowed, harrowed, raked the ground three times, and pulverized it with a mattock, before planting seed. Unfortunately the high evaporation rate resulted in gradual salinity of the fields. By the Ur III period, farmers had converted from wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley as their principle crop.

Sumerians harvested during the dry fall season in three-person teams consisting of a reaper, a binder, and a sheaf arranger. The farmers would use threshing wagons to separate the cereal heads from the stalks and then use threshing sleds to disengage the grain. They then winnowed the grain/chaff mixture.

Architecture

The Tigris-Euphrates plain lacked minerals and trees. Sumerian structures were made of plano-convex mudbrick, not fixed with mortar or cement. Mud-brick buildings eventually deteriorate, and so they were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This constant rebuilding gradually raised the level of cities, so that they came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resultant hills are known as tells, and are found throughout the ancient Near East.

The most impressive and famous of Sumerian buildings are the ziggurats, large layered platforms which supported temples. Some scholars have theorized that these structures might have been the basis of the Tower of Babel described in the Book of Genesis. Sumerian cylinder seals also depict houses built from reeds not unlike those built by the seminomadic Marsh Arabs (Ma'dan) of Southern Iraq until as recently as C.E. 400. The Sumerians also developed the arch. With this structure, they were able to develop a strong type of roof called a dome. They built this by constructing several arches.

Sumerian temples and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques, such as buttresses, recesses, half columns, and clay nails.

Culture

Sumerian culture may be traced to two main centers, Eridu in the south and Nippur in the north. Eridu and Nippur may be regarded as contrasting poles of Sumerian religion.

The deity Enlil, around whose sanctuary Nippur had grown up, was considered lord of the ghost-land, and his gifts to mankind were said to be the spells and incantations that the spirits of good or evil were compelled to obey. The world he governed was a mountain (E-kur from E= house and Kur= Mountain); the creatures that he had made lived underground.

Eridu, on the other hand, was the home of the culture god Enki (absorbed into Babylonian mythology as the god Ea), the god of beneficence, ruler of the freshwater depths beneath the earth (the Abzu from Ab= water and Zu= far), a healer and friend to humanity who was thought to have given us the arts and sciences, the industries and manners of civilization; the first law-book was considered his creation. Eridu had once been a seaport, and it was doubtless its foreign trade and intercourse with other lands that influenced the development of its culture. Its cosmology was the result of its geographical position: the earth, it was believed, had grown out of the waters of the deep, like the ever widening coast at the mouth of the Euphrates. Long before history is recorded, however, the cultures of Eridu and Nippur had coalesced. While Babylon seems to have been a colony of Eridu, Eridu's immediate neighbor, Ur, may have been a colony of Nippur, since its moon god was said to be the son of Enlil of Nippur. However, in the admixture of the two cultures, the influence of Eridu was predominant. The Code of Hammurabi was based on Sumerian Law. The ancient Sumerian flood myth, similar to the Epic of Gilgamesh suggests that the development of City-States was thought to be a way to ensure that peace would prevail.[9] Treaties from ancient Sumeria indicate a preference for solving disputes through negotiation. For the Sumerians, commerce and trade was better than conflict.

Though women were protected by late Sumerian law and were able to achieve a higher status in Sumer than in other contemporary civilizations, the culture was male-dominated.

There is much evidence that the Sumerians loved music. It seemed to be an important part of religious and civic life in Sumer. Lyres were popular in Sumer.

Economy and trade

Discoveries of obsidian from far-away locations in Anatolia and lapis lazuli from northeastern Afghanistan, beads from Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and several seals inscribed with the Indus Valley script suggest a remarkably wide-ranging network of ancient trade centered around the Persian Gulf.

The Epic of Gilgamesh refers to trade with far lands for goods such as wood that were scarce in Mesopotamia. In particular, cedar from Lebanon was prized.

The Sumerians used slaves, although they were not a major part of the economy. Slave women worked as weavers, pressers, millers, and porters.

Sumerian potters decorated pots with cedar oil paints. The potters used a bow drill to produce the fire needed for baking the pottery. Sumerian masons and jewelers knew and made use of alabaster (calcite), ivory, gold, silver, carnelian and lapis lazuli.

Military

The almost constant wars among the Sumerian city-states for 2000 years helped to develop the military technology and techniques of Sumer to a high level. The first war recorded was between Lagash and Umma in 2525 B.C.E. on a stele called the Stele of Vultures. It shows the king of Lagash leading a Sumerian army consisting mostly of infantry. The infantrymen carried spears, equipped with copper helmets and leather shields. The spearmen are shown arranged in a phalanx formation, which required training and discipline, and so implies they were professional soldiers.

The Sumerian military used carts harnessed to onagers. These early chariots functioned less effectively in combat than did later designs, and some have suggested that these chariots served primarily as transports, though the crew carried battle-axes and lances. The Sumerian chariot comprised a four or two-wheeled device manned by a crew of two and harnessed to four onagers. The cart was composed of a woven basket and the wheels had a solid three-piece design.

Sumerian cities were surrounded by defensive walls. The Sumerians engaged in siege warfare between their cities, but the mudbrick walls failed to deter some foes.

Religion

Like other cities of Asia Minor and the Mediterranean, Sumer was a polytheistic, or henotheistic, society. There was no organized set of gods, with each city-state having its own patrons, temples, and priest-kings; but the Sumerians were probably the first to write down their beliefs. Sumerian beliefs were also the inspiration for much of later Mesopotamian mythology, religion, and astrology.

The Sumerians worshipped Anu as the primary god, equivalent to "heaven"—indeed, the word "an" in Sumerian means "sky," and his consort Ki, meaning "earth." Collectively the Gods were known as Anunnaki ((d)a-nun-na-ke4-ne = "offspring of the lord"). An's closest cohorts were Enki in the south at the Abzu temple in Eridu, Enlil in the north at the Ekur temple of Nippur and Inana, the deification of Venus, the morning (eastern) and evening (western) star, at the Eanna temple (shared with An) at Uruk. The sun was Utu, was worshipped at Sippar, the moon was Nanna, worshipped at Ur and Nammu or Namma was one of the names of the Mother Goddess, probably considered to be the original matrix; there were hundreds of minor deities. The Sumerian gods (Sumerian dingir, plural dingir-dingir or dingir-a-ne-ne) thus had associations with different cities, and their religious importance often waxed and waned with the political power of the associated cities. The gods were said to have created human beings from clay for the purpose of serving them. The gods often expressed their anger and frustration through earthquakes and storms: the gist of Sumerian religion was that humanity was at the mercy of the gods.

Sumerians believed that the universe consisted of a flat disk enclosed by a tin dome. The Sumerian afterlife involved a descent into a gloomy netherworld to spend eternity in a wretched existence as a Gidim (ghost).

Sumerian temples consisted of a forecourt, with a central pond for purification (the Abzu). The temple itself had a central nave with aisles along either side. Flanking the aisles would be rooms for the priests. At one end would stand the podium and a mudbrick table for animal and vegetable sacrifices. Granaries and storehouses were usually located near the temples. After a time the Sumerians began to place the temples on top of multi-layered square constructions built as a series of rising terraces: the ziggurats.

Technology

Examples of Sumerian technology include: the wheel, cuneiform, arithmetic and geometry, irrigation systems, sumerian boats, lunisolar calendar, bronze, leather, saws, chisels, hammers, braces, bits, nails, pins, rings, hoes, axes, knives, lancepoints, arrowheads, swords, glue, daggers, waterskins, bags, harnesses, armor, quivers, scabbards, boots, sandal (footwear), harpoons, and beer.

The Sumerians had three main types of boats:

- skin boats comprising of animal skins and reeds

- clinker-built sailboats stitched together with hair, featuring bitumen waterproofing

- wooden-oared ships, sometimes pulled upstream by people and animals walking along the nearby banks

Language and writing

The most important archaeological discoveries in Sumer are a large number of tablets written in Sumerian. Sumerian pre-cuneiform script has been discovered on tablets dating to around 3500 B.C.E.

The Sumerian language is generally regarded as a language isolate in linguistics because it belongs to no known language family; Akkadian belongs to the Afro-Asiatic languages. There have been many failed attempts to connect Sumerian to other language groups. It is an agglutinative language; in other words, morphemes ("units of meaning") are added together to create words.

Sumerians invented picture-hieroglyphs that developed into later cuneiform, and their language vies with Ancient Egyptian for credit as the oldest known written human language. An extremely large body of hundreds of thousands of texts in the Sumerian language has survived, the great majority of these on clay tablets. Known Sumerian texts include personal and business letters and transactions, receipts, lexical lists, laws, hymns and prayers, magical incantations, and scientific texts including mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Monumental inscriptions and texts on different objects like statues or bricks are also very common. Many texts survive in multiple copies because they were repeatedly transcribed by scribes-in-training. Sumerian continued to be the language of religion and law in Mesopotamia long after Semitic speakers had become the ruling race.

Understanding Sumerian texts today can be problematic even for experts. Most difficult are the earliest texts, which in many cases don't give the full grammatical structure of the language.

Legacy

Most authorities credit the Sumerians with the invention of the wheel, initially in the form of the potter's wheel. The new concept quickly led to wheeled vehicles and mill wheels. The Sumerians' cuneiform writing system is the oldest there is evidence of (with the possible exception of the highly controversial Old European Script), pre-dating Egyptian hieroglyphics by at least 75 years. The Sumerians were among the first formal astronomers, correctly formulating a heliocentric view of the solar system, to which they assigned five planets (all that can be seen with the naked eye).

They invented and developed arithmetic using several different number systems including a Mixed radix system with an alternating base 10 and base 6. This sexagesimal system became the standard number system in Sumer and Babylonia. Using this sexagesimal system they invented the clock with its 60 seconds, 60 minutes, and 12 hours, and the 12 month calendar which is still in use. They may have invented military formations and introduced the basic divisions between infantry, cavalry and archers. They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails, and government records. The first true city states arose in Sumer, roughly contemporaneously with similar entities in what is now Syria and Israel. Several centuries after their invention of cuneiform, the practice of writing expanded beyond debt/payment certificates and inventory lists and was applied for the first time about 2600 B.C.E. to written messages and mail delivery, history, legend, mathematics, astronomical records and other pursuits generally corresponding to the fields occupying teachers and students ever since. Accordingly, the first formal schools were established, usually under the auspices of a city-state's primary temple.

Finally, the Sumerians ushered in the age of intensive agriculture and irrigation. Emmer wheat, barley, sheep (starting as moufflon) and cattle (starting as aurochs) were foremost among the species cultivated and raised for the first time on a grand scale. These inventions and innovations easily place the Sumerians among the most creative cultures in human pre-history and history.

However, the Sumerians' misuse of their land ultimately led to their own downfall. The river that they used for irrigation flooded their fields of wheat with water. Over time, salination—the build of salt—occurred in their soils, thus decreasing productivity. Less and less wheat could be harvested. The Sumerians tried switching to barley, a more salt-tolerant crop. This worked for a while, but salt continued to accumulate, ultimately leading to loss of yields and the starvation of their people.

Notes

- ↑ Sumerian Legal System Crystalinks. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ John Alan Halloran, Meaning of Sumer? Sumerian Questions and Answers. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Sumerian History Crystalinks. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Thorkild Jacobsen, Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971, ISBN 0674898109).

- ↑ William R. Thompson, "Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation," Journal of World Systems Research X (Fall 2004): 613-652. ISSN 1076-156X

- ↑ Donald Alexander Mackenzie, (original 1909) Footprints of Early Man (Obscure Press, 2006, ISBN 1846644186).

- ↑ Robert McCormick Adams, Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981, ISBN 9780226005447).

- ↑ Azar Gat, "Why City-States Existed?" 125-138, in Mogens H. Hansen, (ed) A Comparative Study of 6 City-States (Copenhagen: The Danish Royal Academy, 2002).

- ↑ Sumerian Myth Grand Valley State University. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Robert McCormick. Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981. ISBN 9780226005447

- Ascalone, Enrico. Mesopotamia: Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians (Dictionaries of Civilizations; 1). Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 0520252667.

- Bottéro, Jean. Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001 ISBN 9780801868627

- Crawford, Harriet. Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 9780521381758

- Gelb, Ignace Jay. Old Akkadian Writing and Grammar, Second editon. Materials for the Assyrian Dictionary 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Halloran, John Alan. Sumerian Lexicon. A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language. Logogram Publishing, Los Angeles 2006. ISBN 0978642902

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971. ISBN 0674898109

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.E. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997. ISBN 9780585126975

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer. Garden City, NY: Doubleday / Anchor, 1959.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963

- Leick, Gwendolyn. Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. London: Penguin, 2002 ISBN 9780140265743

- Lloyd, Seton. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978. ISBN 9780500780077

- Mackenzie, Donald Alexander. (original 1909) Footprints of Early Man. reprint ed. Obscure Press, 2006. ISBN 1846644186

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea. Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998. ISBN 9780313294976

- Postgate, J. Nicholas. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq, Third ed. reprint Penguin, [1965] 1993. ISBN 014012523X

- Schomp, Virginia. Ancient Mesopotamia: The Sumerians, Babylonians, And Assyrians. NY: Franklin Watts, 2004. ISBN 9780531118184

- Sumer: Cities of Eden (Timelife: Lost Civilizations). Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1993. ISBN 0809498871

- Westenholz, Aage. "Old Sumerian and Old Akkadian Texts in Philadelphia Chiefly from Nippur. Pt. 1. Literary and Lexical Texts and the Earliest Administrative Documents from Nippur." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 36 (4) (Oct., 1977): 299-302

- Woolley, C. Leonard. The Sumerians. NY: W. W Norton, 1965. ISBN 9780393002928

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- The History of the Ancient Near East

- Sumerian Language Page, perhaps the oldest Sumerian website on the web (it dates back to 1996), features compiled lexicon, detailed FAQ, extensive links, and so on.

- ETCSL: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature has complete translations of more than 400 Sumerian literary texts.

- PSD: The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary, while still in its initial stages, can be searched on-line, from August 2004.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.