Swastika

The swastika (from Sanskrit: svástika स्वस्तिक ) is an equilateral cross with its arms bent at right angles, in either right-facing (卐) form or its mirrored left-facing (卍) form. The swastika can also be drawn as a traditional swastika, but with a second 90° bend in each arm. Archaeological evidence of swastika-shaped ornaments dates from the Neolithic period. It occurs mainly in the cultures that are in modern day India and the surrounding area, sometimes as a geometrical motif and sometimes as a religious symbol. It was long widely used in major world religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

Though once commonly used all over much of the world without stigma, because of its iconic usage in Nazi Germany the symbol has become controversial in the Western world.

Etymology and alternative names

The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit word svastik (in Devanagari, स्वस्तिक), meaning any lucky or auspicious object, and in particular a mark made on persons and things to denote good luck. It is composed of su- (cognate with Greek ευ-, eu-), meaning "good, well" and asti, a verbal abstract to the root as "to be" (cognate with the Romance copula, coming ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root *h1es-); svasti thus means "well-being." The word in this sense is first used in the Harivamsa.[1]

The Hindu Sanskrit term has been in use in English since 1871, replacing gammadion (from Greek γαμμάδιον).

Alternative historical English spellings of the Sanskrit word include suastika, swastica and svastica. Alternative names for the shape are:

- crooked cross

- cross cramponned, ~nnée, or ~nny (in heraldry), as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (German: Winkelmaßkreuz)

- ugunskrusts (fire cross), also pērkonkrusts (thundercross), kāškrusts (hook-cross), Laimas krusts (Laima's cross).

- fylfot, possibly meaning "four feet," chiefly in heraldry and architecture (See fylfot for a discussion of the etymology)

- gammadion, tetragammadion (Greek: τέτραγαμμάδιον), or cross gammadion (Latin: crux gammata; Old French: croix gammée), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ (gamma)

- hook cross (German: Hakenkreuz);

- sun wheel, a name also used as a synonym for the sun cross

- tetraskelion (Greek: τετρασκέλιον), "four legged," especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare triskelion (Greek: τρισκέλιον))

- Mundilfari an Old Norse term has been associated in modern literature with the swastika.[2]

- Thor's hammer, from its supposed association with Thor, the Norse god of the weather, but this may be a misappropriation of a name that properly belongs to a Y-shaped or T-shaped symbol.[3] The swastika shape appears in Icelandic grimoires wherein it is named Þórshamar.

- The Tibetan swastika is known as nor bu bzhi -khyil, or quadruple body symbol, defined in Unicode at codepoint U+0FCC ࿌.

Origin Hypothesis

The ubiquity of the swastika symbol is easily explained by its being a very simple shape that will arise independently in any basket-weaving society. The swastika is a repeating design, created by the edges of the reeds in a square basket-weave. Other theories attempt to establish a connection via cultural diffusion or an explanation along the lines of Carl Jung's collective unconscious.

The genesis of the swastika symbol is often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the "sun wheel" of Bronze Age religion.

In his book Comet Carl Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.

In Life's other secret, Ian Stewart suggests that during states of altered consciousness parallel waves of neural activity sweep across the visual cortex, producing a swirling swastika-like image, due to the way quadrants in the field of vision are mapped to opposite areas in the brain. Alexander Cunningham has suggested that the shape arose from a combination of Brahmi characters abbreviating the word su-astí.

While this sign has been found in many cultures it is referred to as Swastika only in Sanskrit and related languages.

The swastika motif is found in isolated artifacts from the Paleolithic and Bronze age, but the earliest consistent use of swastika motifs in the archaeological record date to the Neolithic, in a range from Iran to Russia.

Geometry

Geometrically, the swastika can be regarded as an irregular icosagon or 20-sided polygon. The arms are of varying width and are often rectilinear (but need not be). However, the proportions of the Nazi swastika were fixed: they were based on a 5x5 grid.[4]

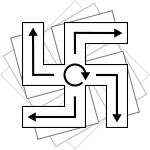

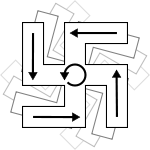

Characteristic is the 90° rotational symmetry (that is, the symmetry of the cyclic group C4h) and chirality, hence the absence of reflectional symmetry, and the existence of two versions that are each other's mirror image.

The mirror-image forms are often described as:

- clockwise and counterclockwise;

- left-facing and, as depicted across, right-facing;

- left-hand and right-hand.

"Left-facing" and "right-facing" are used mostly consistently. In an upright swastika, the upper arm faces either the viewer's left (卍) or right (卐). The other two descriptions are ambiguous as it is unclear whether they refer to the direction of the bend in each arm or to the implied rotation of the symbol. If the latter, whether the arms lead or trail remains unclear. However, "clockwise" usually refers to the "right-facing" swastika. The terms are used inconsistently (sometimes even by the same writer), which is confusing and may obfuscate an important point, that the rotation of the swastika may have symbolic relevance.

Symbolism

Traditionally the swastika has been used as a symbol of good luck, welfare, prosperity or victory. One interpretation of the swastika is derived from the ancient mythological symbolism of Shakti (Devanagari: शक्ति, Shakti) (represented by the vertical line) dancing upon Shiva (Devanagari: शिव, Shiv) (represented by the horizontal line). Philosophically this may be understood as the two aspects of Brahma (Devanagari: ब्रह्म, Brahma): consciousness and energy interacting to give expression to the universe. The circular movement of this cross may be interpreted as the circular movement of the rising kundalini (Devanagari: कुण्डलिनी).

If seen as a cross, the four lines emanate from the center to the four cardinal directions, and this is commonly associated with the Sun. Other proposed correspondences are to the visible rotation of the night sky in the Northern Hemisphere around the pole star.

Art and architecture

The swastika is common as a design motif in current Hindu architecture and Indian artwork as well as in ancient Western architecture, frequently appearing in mosaics, friezes, and other works across the ancient world. It is often part of a repeating pattern. In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese art, a common pattern comprises left and right facing swastikas joined by lines.[5] In Greco-Roman art and architecture, and in Romanesque and Gothic art in the West, the swastika is more commonly found as a repeated element in a border or tessellation and can be seen in more recent buildings as a neoclassical element. A swastika border is one form of meander, and the individual swastikas in such a border are sometimes called Greek keys.[6]

Ceramic tiles with a swastika design have appeared in many parts of the world including the United States in the early twentieth century. A number of the buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places or as Unesco World Heritage sites, and are considered worthy of historical preservation.

The Primate's Palace in Bratislava has security grills on the ground floor that incorporate swastikas in their design. (See Image of the Primate's Palace)

World Religions

The swastika symbol has been used either as a decorative or auspicious sign by all of the major world religions. The swastika is a pervasive symbol in some religions, and has a scant presence in others.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the two symbols represent the two forms of the creator god Brahma: facing right it represents the evolution of the universe (Devanagari: प्रवृत्ति, Pravritti), facing left it represents the involution of the universe (Devanagari: निवृत्ति, Nivritti). It is also seen as pointing in all four directions (north, east, south and west) and thus signifies stability and groundedness. Its use as a sun symbol can first be seen in its representation of the god Surya (Devanagari: सूर्य, Sun).

The swastika is considered extremely holy and auspicious by all Hindus, and is found all over Hindu temples, signs, altars, pictures and iconography where it is sacred. It is used in Hindu weddings, festivals, ceremonies, houses and doorways, clothing and jewelry, motor transport and even decorations on food items such as cakes and pastries.

The Swastika is one of the 108 symbols of Hindu deity Vishnu and represents the sun's rays, upon which life depends.

Buddhism

The symbol as it is used in Buddhist art and scripture is known in Japanese as a manji (literally, "the character for eternality" 萬字), and represents Dharma, universal harmony, and the balance of opposites. When facing left, it is the omote (front) manji, representing love and mercy. Facing right, it represents strength and intelligence, and is called the ura (rear) manji. Balanced manji are often found at the beginning and end of Buddhist scriptures (outside India).

Jainism

Jainism gives even more prominence to the swastika than does Hinduism. It is a symbol of the seventh Jina (Saint), the Tirthankara Suparsva. In the Svetambar (Devanagari: श्वेताम्बर) Jain tradition, it is also one of the symbols of the ashta-mangalas (Devanagari: अष्ट मंगल). It is considered to be one of the 24 auspicious marks and the emblem of the seventh arhat of the present age.

All Jain temples and holy books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice around the altar.[7]

Abrahamic religions

The swastika was not widely utilized by followers of the Abrahamic religions. Where it does exist, it is often purely decorative or, at most, a symbol of good luck. One example of scattered use is the floor of the synagogue at Ein Gedi, built during the Roman occupation of Judea, which was decorated with a swastika.[8]

In Christianity, the swastika is sometimes used as a hooked version of the Christian Cross, the symbol of Christ's victory over death. Some Christian churches built in the Romanesque and Gothic eras are decorated with swastikas, carrying over earlier Roman designs.

The Muslim "Friday" mosque of Isfahan, Iran and the Taynal Mosque in Tripoli, Lebanon both have swastika motifs.

Native American traditions

The swastika shape was used by some Native Americans. It has been found in excavations of Mississippian-era sites in the Ohio valley. It was widely used by many southwestern tribes, most notably the Navajo. Among various tribes, the swastika carried different meanings. To the Hopi it represented the wandering Hopi clan; to the Navajo it was one symbol for a whirling winds (tsil no'oli'), a sacred image representing a legend that was used in healing rituals.[9]

In the culture of the Kuna people of Kuna Yala, Panama a swastika shape symbolizes the octopus that created the world; its tentacles, pointing to the four cardinal points. The Kuna flag is based on the swastika shape, and remains the official flag of Kuna Yala.[10]

New religious movements

Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society uses a swastika as part of its seal, along with an Aum, a hexagram, a Star of David, an Ankh and an Ouroboros. Unlike the much more recent Raëlian movement (see below), the Theosophical Society symbol has been free from controversy, and the seal is still used.[11]

Raëlian Movement

The Raëlian Movement, who believe that Extra-Terrestrials originally created all life on earth, use a symbol that is often the source of considerable controversy: an interlaced Star of David and a Swastika. The Raelians state that the Star of David represents infinity in space whereas the swastika represents infinity, or the cyclical nature of time.[12] In 1991, the symbol was changed to remove the Swastika, out of respect to the victims of the holocaust, but as of 2007 has been restored to its original form.[13]

Ananda Marga

The Tantra-based religious movement Ananda Marga (Devanagari: आनन्द मार्ग, meaning Way to Happiness) uses a motif similar to the Raëlians, but in their case the apparent star of David is defined as equilateral triangles representing a balance of the inner and outer life, with no specific reference to Jewish culture.[14]

Falungong

The Falungong qigong movement uses a symbol that features a large swastika surrounded by four smaller (and rounded) ones, interspersed with yin-and-yang symbols. The usage is taken from traditional Chinese symbolism, and here alludes to chakra-like portion of the esoteric human anatomy, located in the stomach (see Dantien).

Neopaganism

The Odinic Rite claims the "fylfot" as a "holy symbol of Odinism," citing the pre-Christian Germanic use of the symbol.

Secular cultures

The swastika has an ancient history in Europe, appearing on artifacts from Indo-European cultures and is a sacred symbol in world religions, making the swastika ubiquitous in both historical and contemporary society.

The discovery of the Indo-European language group in the 1790s led to a great effort by archaeologists to link the pre-history of European people to the ancient "Aryans." Following his discovery of objects bearing the swastika in the ruins of Troy, Heinrich Schliemann consulted two leading Sanskrit scholars of the day, Emile Burnouf and Max Müller. Schliemann connected it with similar shapes found on ancient pots in Germany, and theorized that the swastika was a "significant religious symbol of our remote ancestors," linking Germanic, Greek and Indo-Iranian cultures.

Since its adoption by the Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler, the swastika has been associated with Nazism, fascism, racism (white supremacy), the Axis powers in World War II, and the Holocaust in much of the West.

Baltic

The swastika is one of the most common symbols used throughout Baltic art. The symbol is known as either Ugunskrusts, the "Fire cross" (rotating counter-clockwise), or Pērkonkrusts, the "Thunder cross" (rotating clock-wise), and was mainly associated with Pērkons, the god of Thunder.

Celtic

The bronze frontspiece of a ritual pre-Christian (ca 350-50 B.C.E.) shield found in the River Thames near Battersea Bridge (hence "Battersea Shield") is embossed with 27 swastikas in bronze and red enamel.[15]

An Ogham stone found in Anglish, Co Kerry (CIIC 141) was modified into an early Christian gravestone, and was decorated with a cross pattée and two swastikas.[16]

At the Northern edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, there is a swastika-shaped pattern engraved in a stone known as the Swastika Stone.[17][18]

Finnish

In Finland the swastika was often used in traditional folk art products, as a decoration or magical symbol on textiles and wood.

A design by Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela of 1918, the Cross of Liberty has a swastika pattern in the arms of the cross. The Cross of Liberty is depicted in the upper left corner of the flag of the President of Finland.[19]

A traditional symbol that incorporates a swastika, the tursaansydän, is used by scouts in some instances and a student organization. The village of Tursa uses the tursaansydän as a kind of a certificate of genuineness of products made there. Traditional textiles are still being made with swastikas as a part of traditional ornaments.

Germanic

The swastika shape (also called a fylfot) appears on various Germanic Migration Period and Viking Age artifacts, such as the third century Værløse Fibula from Zealand, Denmark, the Gothic spearhead from Brest-Litovsk, Russia, the ninth century Snoldelev Stone from Ramsø, Denmark, and numerous Migration Period bracteates drawn left-facing or right-facing.[20]

Hilda Ellis Davidson theorized that the swastika symbol was associated with Thor and cites "many examples" of the swastika symbol from Anglo-Saxon graves of the pagan period, with particular prominence on cremation urns from the cemeteries of East Anglia.

Slavic

The swastika shape was also present in pre-Christian Slavic mythology. It was dedicated to the sun god Svarog (Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian Сварог) and called kolovrat, (Polish kołowrót, Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian коловрат or коловорот, Serbian коловрат/kolovrat) or swarzyca.

For the Slavs the swastika is a magic sign manifesting the power and majesty of the sun and fire. It was often used as an ornament decorating ritualistic utensils of a cult cinerary urns with ashes of the dead.

The Swastika was also a heraldic symbol, for example on the Boreyko coat of arms, used by noblemen in Poland and Ukraine. In the ninteenth century the swastika was one of the Russian empire's symbols; it was even placed in coins as a background to the Russian eagle.

Basque

The Lauburu (Basque for "four heads") is the traditional Basque emblem. The cross has four comma-shaped heads similar to the Japanese tomoe and in modern times it has been associated with the curvilinear swastika. It is a clock-wise turning Swastika with rounded edges.[21]

India, Nepal and Sri Lanka

In South Asia, the swastika remains ubiquitous as a symbol of wealth and good fortune. Many businesses and other organizations, such as the Ahmedabad Stock Exchange and the Nepal Chamber of Commerce,[22] use the swastika in their logos. The red swastika was suggested as an emblem of International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in India and Sri Lanka, but the idea was not implemented[23] Swastikas can be found practically everywhere in Indian cities, on buses, buildings, auto-rickshaws, and clothing.

Tajikistan

In 2005, authorities in Tajikistan called for the widespread adoption of the swastika as a national symbol. President Emomali Rahmonov declared the swastika an "Aryan" symbol and 2006 to be "the year of Aryan culture," which would be a time to “study and popularize Aryan contributions to the history of the world civilization, raise a new generation (of Tajiks) with the spirit of national self-determination, and develop deeper ties with other ethnicities and cultures.”[24]

As the symbol of Nazism

- Further information: Nazism

Since World War II, the swastika is often associated with the flag of Nazi Germany and the Nazi Party in the Western world.

When Hitler created a flag for the Nazi Party, he sought to incorporate both the swastika and "those revered colors expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honor to the German nation." (Red, white, and black were the colors of the flag of the old German Empire.) He also stated: "As National Socialists, we see our program in our flag. In red, we see the social idea of the movement; in white, the nationalistic idea; in the swastika, the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work, which as such always has been and always will be anti-Semitic."[26]

The use of the swastika was associated by Nazi theorists with their conjecture of Aryan cultural descent of the German people.

Following the Nordicist version of the Aryan invasion theory, the Nazis claimed that the early Aryans of India, from whose Vedic tradition the swastika sprang, were the prototypical white invaders. It was also widely believed that the Indian caste system had originated as a means to avoid racial mixing.[27] The concept of Racial purity was an ideology central to Nazism, even though it is now considered unscientific.

For Alfred Rosenberg, the theologian of National Socialism, the Aryans of India were both a model to be imitated and a warning of the dangers of the spiritual and racial "confusion" that, he believed, arose from the close proximity of races. Thus, they saw fit to co-opt the sign as a symbol of the Aryan master race. The use of the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan race dates back to writings of Emile Burnouf. Following many other writers, the German nationalist poet Guido von List believed it to be a uniquely Aryan symbol.

On March 14, 1933, shortly after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany, the NSDAP flag was hoisted alongside Germany's national colors. It was adopted as the sole national flag on September 15, 1935 (see Nazi Germany).

Post-Nazi stigmatization

Because of its use by Hitler and the Nazis and, in modern times, by neo-Nazis and other hate groups, the swastika is today largely associated with Nazism and white supremacy in most Western countries. As a result, all of its use, or its use as a Nazi or hate symbol is prohibited in some jurisdictions and many buildings that have contained the symbol as decoration have had the symbol removed.

Finland

Finland might be a notable exception amongst the modern Western countries regarding the public attitude towards the swastika.

All the Unit Colors of the Finnish Air Force feature the same basic design, with a swastika as a central element. This is the Unit Color of the Finnish Air Force Academy.

Brazil

The use of the swastika in conjunction with any other Nazi allusion, and also its manufacture, distribution or broadcasting, is a crime as dictated by law 7.716/89 from 1989. The penalty is a fine and two to five years in prison.

European Union

The European Union's executive Commission proposed a European Union wide anti-racism law in 2001, but European Union states failed to agree on the balance between prohibiting racism and freedom of expression.[28] An attempt to ban the swastika across the EU in early 2005 failed after objections from the British Government and others. Another proposal by Germany to ban the swastika was dropped by Berlin from the proposed European Union wide anti-racism laws on January 29, 2007.[28]

Germany

The German (and Austrian) postwar criminal code makes the public showing of the Hakenkreuz (the swastika) and other Nazi symbols illegal and punishable, except for scholarly reasons. It is even censored from the lithographs on boxes of model kits, and the decals that come in the box. It is also censored from the reprints of 1930s railway timetable published by Bundesbahn. The swastikas on Hindu and Jain temples are exempt, as religious symbols cannot be banned in Germany.

United States

The swastika symbol was popular[29] as a good luck or religious/spiritual symbol in the United States, prior to its association with Nazi Germany. The symbol also appeared on tiles, lampposts, metal valves, tools, surfboards, stock certificates, brand names, place names, medals, commercial tokens, postcards, souvenirs, rugs and clothing.

The shoulder patch of the 45th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit from the Southwestern United States, was originally a yellow swastika on a red diamond, in the context of a religious/mystical symbol of the Native American tribes of that region. As war with Nazi Germany became imminent in the late 1930s, the swastika was replaced by a yellow thunderbird emblem.

Satirical use

A book featuring "120 Funny Swastika Cartoons" was published in 2008 by New York Cartoonist Sam Gross. The author said he created the cartoons in response to excessive news coverage given to swastika vandals, that his intent "...is to reduce the swastika to something humorous."[30]

The powerful symbolism acquired by the swastika has often been used in graphic design and propaganda as a means of drawing Nazi comparisons; examples include the cover of Stuart Eizenstat's 2003 book Imperfect Justice,[31] publicity materials for Costa-Gavras's 2002 film Amen,[32] and a billboard that was erected opposite the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, Cuba, in 2004, which juxtaposed images of the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse pictures with a swastika.

Image Gallery

The tombstone of abbot Simon de Gillans (-1345), with a stole depicting swastikas. Musée de Cluny, Paris.

Election propaganda for the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) in Kathmandu

Hindu Swastika sign in a car in Canada.

See also

- Fascist symbolism

- Karl Haushofer

Notes

- ↑ Monier-Williams (1899), s.v. "svastika." The Ramayana does have the word, but in an unrelated sense of "one who utters words of eulogy." The Mahabharata has the word in the sense of "the crossing of the arms or hands on the breast." Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana also use the word in the sense of "a dish of a particular form" and "a kind of cake." The word doesn't occur in Vedic Sanskrit.

- ↑ The History of the Swastika Runic Symbol Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Wilson

- ↑ "Swastika Flag Specifications and Construction Sheet (Germany)." Flags of the World. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Sayagata 紗綾形." Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Lara Nagy and Jane Vadnal, "Glossary Medieval Art and Architecture," "Greek key or meander", University of Pittsburgh 1997–98. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas Wilson. 1896. The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol and Its Migration. (Cosmo. ISBN 076610818X)

- ↑ "Ein Gedi: An Ancient Oasis Settlement." Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. November 23, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Dottie Indyke, "The History of an Ancient Human Symbol." April 4, 2005. originally from The Wingspread Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe, Taos and Albuquerque, Volume 15. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Panama - Native Peoples, from Flags of the World. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ The Theosophical Society-Adyar - Emblem Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Pro-Swastika Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Raelianews: The Official Raelian Symbol gets its swastika back Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Ananda Marga.org [1] Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ The Battersea Shield British Museum Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ CISP entry Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ (Photo), Retrieved February 24, 2009; In the figure in the foreground of the picture linked is a twentieth century replica

- ↑ The original carving can be seen a little farther away, at left center; [2] Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ The President of Finland: Flag Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Margrethe, Queen, Poul Kjrum, Rikke Agnete Olsen, 1990, Oldtidens Ansigt: Faces of the Past, (ISBN 9788774682745), 148

- ↑ The truth and legend of the swastika [3] Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ ::nepalnews.com daily picture (News from Nepal as it happens):: Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ [Tajikistan: Officials Say Swastika Part Of Their Aryan Heritage - [Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty © 2008]] Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Bender. Deutschland Erwache (ISBN 0912138696)

- ↑ text of Mein Kampf at Project Gutenberg of Australia Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ [4] Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Ethan McNern. Swastika ban left out of EU's racism law, The Scotsman, January 30, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ "USA - Coca Cola Swastika lucky watch fob" Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ David Kaufman, "Cartoons COunter Swastika Shock", The Forward, February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Harry Kreisler. "Conversation with Stuart E. Eizenstat." Conversations with History. Institute of International Studies, UC Berkeley. April 30, 2003. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Swastika film poster escapes ban." BBC News. February 21, 2002. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- A critical update to remove unacceptable symbols from the Bookshelf Symbol 7 font. Microsoft Knowledge Base Article 833407. November 8, 2004.

- Aigner, Dennis J. 2000. The Swastika Symbol in Navajo Textiles. Laguna Beach, California: DAI Press. ISBN 097018980X.

- Clarence House issues apology for Prince Harry's Nazi costume. BBC News. January 13, 2005.

- Clube, V. and Napier, B. The Cosmic Serpent. Universe Books, 1982. ISBN 9780876633793

- Enthoven, R.E. The Folklore of Bombay. London: Oxford University Press, 1924. ISBN 9788177551334, 40-45.

- Gardner, N. 2006. Multiple Meanings: The Swastika Symbol. in Hidden Europe, 11: 35–37. Berlin. ISSN 1860-6318

- Jaume Ollé, Željko Heimer, and Norman Martin. "State Flag and Ensign 1935–1945" December 29, 2004. The Reichsdienstflagge.

- Lonsdale, Steven. Animals and the Origin of Dance. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1982 ISBN 9780500012581, 169–181.

- MacCulloch, C.J.A. and John A. Canon (ed.). Mythology of all Races. vol. 8 ("Chinese Mythology" Ferguson, John C.) Marshall Jones Co. Boston, MA 1928, 31. OCLC 297233904

- ManWoman. Gentle Swastika: Reclaiming the Innocence. Cranbrook, B.C., Canada: Flyfoot Press, 2001. ISBN 0968871607.

- Marcus Wendel, Jaume Ollé, et al. "Schutzstaffel/SS" December 14, 2001. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- Morphy, Howard (ed.). Animals into Art (One World Archaeology; vol. 7) London: Unwin Gyman Ltd, 1989. (chapt. 11 Schaafsma, Polly). ISBN 9780044450306

- Norman Martin et al. "Standard of the Leader and National Chancellor 1935–1945." April 9, 2004. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- Roy, Pratap Chandra. The Mahabharata. Munshiram Manoharlal. New Delhi, 1973 (vol. 1 section 13–58, vol. 5 section 2–3). OCLC 2523105

- Schliemann, Henry. Ilios Franklin Square, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1881 . ISBN 9780405098543, 334–353.

- Tan Huay Peng. 1980–1983. Fun with Chinese Characters. Singapore: Federal Publications. ISBN 9810130058.

- The Swastika The earliest known symbol, and its migrations; with observations on the migration of certain industries in prehistoric times. In Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution

- Whipple, Fred L. The Mystery of Comets Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst. Press. 1985. ISBN 9780521324403, 163–167.

- Wilson, Thomas (Curator, Department of Prehistoric Anthropology, U.S. National Museum) (1896).

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- General

- History of the Swastika – (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- The Origins of the Swastika – BBC News

- Early Western use

- BOE_P12.jpg – US Army Air Corp (USAAC) Boeing P-12C

- 55th Pursuit Squadrons swastika-insignia – in 1930s. The USAAC became the United States Air Force in 1941.

- Nazi use

- From Flags of the World (FOTW):

- Origins of the Swastika Flag (Third Reich, Germany) (collection of links and comments)

- Neonazi flags (links to other FOTW pages)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.