| Theodosius I | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | ||

| ||

| Coin featuring Theodosius I | ||

| Reign | August 378 - May 15, 392 (emperor in the east, with Gratian and Valentinian II in the west); May 15, 392 – January 17, 395 (whole empire) | |

| Full name | Flavius Theodosius | |

| Born | January 11 347 | |

| Cauca, modern Spain | ||

| Died | 17 January 395 | |

| Milan | ||

| Buried | Constantinople, Modern Day Istanbul | |

| Predecessor | Valens (in the east); Valentinian II in the west | |

| Successor | Arcadius in the east; Honorius in the west | |

| Issue | By 1) Arcadius, Honorius and Pulcheria (?-385) By 2) Galla Placidia | |

| Father | Theodosius the Elder | |

| Mother | Thermantia | |

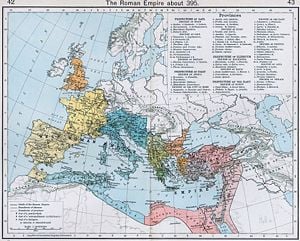

Flavius Theodosius (January 11, 347 – January 17, 395 C.E.), also called Theodosius I and Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379-395. Reuniting the eastern and western portions of the empire, Theodosius was the last emperor of both the Eastern and Western Roman Empire. After his death, the two parts split permanently.

He is also known for making Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire. However, Theodosius I's legacy is controversial: he is lauded as transforming the Roman Empire into a bastion of imperial Christianity, but he is criticized for imposing draconian measures against polytheism, which went against the Christian teaching to love one's neighbor.

Biography

Born in Cauca, in Hispania (modern Coca, Spain), to a senior military officer, Theodosius the Elder, Theodosius accompanied his father to Britannia to help quell the Great Conspiracy in 368 C.E. He was military commander (dux) of Moesia, a Roman province on the lower Danube, in 374 C.E. However, shortly thereafter, and at about the same time as the sudden disgrace and execution of his father, Theodosius retired to Cauca. The reason for his retirement, and the relationship (if any) between it and his father's death is unclear. It is possible that he was dismissed from his command by the emperor Valentinian I after the loss of two of Theodosius' legions to the Sarmatians in late 374 C.E.

The death of Valentinian I created political pandemonium. Fearing further persecution on account of his family ties, Theodosius abruptly retired to his family estates where he adapted to the life of a provincial aristocrat.

From 364 to 375 C.E., the Roman Empire was governed by two co-emperors, the brothers Valentinian I and Valens; when Valentinian died in 375 C.E., his sons, Valentinian II and Gratian, succeeded him as rulers of the Western Roman Empire. In 378 C.E., after Valens was killed in the Battle of Adrianople, Gratian appointed Theodosius to replace the fallen emperor as co-augustus for the East. Gratian was killed in a rebellion in 383 C.E. After the death in 392 C.E. of Valentinian II, whom Theodosius had supported against a variety of usurpations, Theodosius ruled as sole emperor, defeating the usurper Eugenius on September 6, 394 C.E., at the Battle of the Frigidus (Vipava river, modern Slovenia).

By his first wife, Aelia Flaccilla, he had two sons, Arcadius and Honorius and a daughter, Pulcheria; Arcadius was his heir in the east and Honorius in the west. Both Pulcheria and Aelia Flaccilla died in 385 C.E. By his second wife, Galla, daughter of the emperor Valentinian I, he had a daughter, Galla Placidia, the mother of Valentinian III.

The Goths and their allies entrenched in the Balkans consumed his attention. The Gothic crisis was bad enough that his co-Emperor Gratian relinquished control of the Illyrian provinces and retired to Trier in Gaul to let Theodosius operate without hindrance. A major weakness in the Roman position after the defeat at Adrianople was the recruiting of barbarians to fight against barbarians. In order to reconstruct the Roman Army of the West, Theodosius needed to find able bodied soldiers and so he turned to the barbarians recently settled in the Empire. This caused many difficulties in the battle against barbarians since the newly recruited fighters had little or no loyalty to Theodosius.

Theodosius was reduced to the expensive expedient of shipping his recruits to Egypt and replacing them with more seasoned Romans, but there were still switches of allegiance that resulted in military setbacks. Gratian sent generals to clear Illyria of Goths, and Theodosius was able finally to enter Constantinople on November 24, 380 C.E., after two seasons in the field. The final treaties with the remaining Goth forces, signed October 3, 382 C.E., permitted large contingents of Goths to settle along the Danube frontier in the diocese of Thrace and largely govern themselves.

The Goths settled in the Empire had, as a result of the treaties, military obligations to fight for the Romans as a national contingent, as opposed to being integrated into the Roman forces.[1] However, many Goths would serve in Roman legions and others, as foederati, for a single campaign, while bands of Goths switching loyalties became a destabilizing factor in the internal struggles for control of the Empire. In the last years of Theodosius' reign, one of their emerging leaders named Alaric, participated in Theodosius' campaign against Eugenius in 394 C.E., only to resume his rebellious behavior against Theodosius' son and eastern successor, Arcadius, shortly after Theodosius' death.

After the death of Gratian in 383 C.E., Theodosius' interests turned to the Western Roman Empire, for the usurper Magnus Maximus had taken all the provinces of the West except for Italy. This self-proclaimed threat was hostile to Theodosius' interests, since the reigning emperor Valentinian II, was his ally. Theodosius, however, was unable to do much about Maximus due to his limited military and was forced to keep his attention on local matters. Nevertheless, when Maximus began an invasion into Italy in 387 C.E., Theodosius was forced to take action. The armies of Theodosius and Maximus met in 388 C.E. at Poetovio and Maximus was defeated. On August 28, 388 C.E. Maximus was executed.[2]

Trouble arose again, after Valentinian was found hanging in his room. It was claimed to be a suicide by the magister militum, Arbogast. Arbogast, unable to assume the role of emperor, elected Eugenius, a former teacher of rhetoric. Eugenius started a program of restoration of the Pagan faith, and sought, in vain, Theodosius' recognition. In January of 393, Theodosius gave to his son Honorius the full rank of Augustus in the West, suggesting Eugenius' illegitimacy.[3]

Theodosius campaigned against Eugenius. The two armies faced at the Battle of Frigidus in September of 394.[4] The battle began on September 5, 394 with Theodosius' full frontal assault on Eugenius' forces. Theodosius was repulsed and Eugenius thought the battle to be all but over. In Theodosius' camp the loss of the day decreased morale. It is said that Theodosius was visited by two "heavenly riders all in white"[3] who gave him courage. The next day, the battle began again and Theodosius' forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the Bora,[3] which produces cyclonic winds. The Bora blew directly against the forces of Eugenius and disrupted the line.

Eugenius' camp was stormed and Eugenius was captured and soon after executed. Thus, Theodosius became the only emperor of both the eastern and Western parts of the Roman Empire.

Support for Christianity

Theodosius promoted Nicene Trinitarianism within Christianity and Christianity within the empire. In 391 he declared Christianity as the only legitimate imperial religion, ending state support for the traditional Roman religion.

In the fourth century C.E., the Christian Church was wracked with controversy over the divinity of Jesus Christ, his relationship to God the Father, and the nature of the Trinity. In 325 C.E., Constantine I had convened the Council of Nicea, which asserted that Jesus, the Son, was equal to the Father, one with the Father, and of the same substance (homoousios in Greek). The council condemned the teachings of the theologian Arius: that the Son was a created being and inferior to God the Father, and that the Father and Son were of a similar substance (homoiousios in Greek) but not identical. Despite the council's ruling, controversy continued. By the time of Theodosius' accession, there were still several different church factions that promoted alternative Christologies.

While no mainstream churchmen within the Empire explicitly adhered to Arius (a presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt) or his teachings, there were those who still used the homoiousios formula, as well as those who attempted to bypass the debate by merely saying that Jesus was like (homoios in Greek) God the Father, without speaking of substance (ousia). All these non-Nicenes were frequently labeled as Arians (i.e., followers of Arius) by their opponents, though they would not have identified themselves as such.

The Emperor Valens had favored the group who used the homoios formula; this theology was prominent in much of the East and had under the sons of Constantine the Great gained a foothold in the West. Theodosius, on the other hand, cleaved closely to the Nicene Creed: this was the line that predominated in the West and was held by the important Alexandrian church.

Two days after Theodosius arrived in Constantinople (November 24, 380 C.E.), Theodosius expelled the non-Nicene bishop, Demophilus of Constantinople, and appointed Meletius to patriarch of Antioch, and appointed Gregory of Nazianzus one of the Cappadocian Fathers from Antioch (which is now Turkey) to patriarch of Constantinople. Theodosius had just been baptized, by bishop Acholius of Thessalonica, during a severe illness, as was common in the early Christian world. In February, he and Gratian published an edict that all their subjects should profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (i.e., the Nicene faith). The move was mainly thrust at the various beliefs that had arisen out of Arianism, but smaller dissident sects, such as the Macedonians, were also prohibited.

In May, 381 C.E., Theodosius summoned a new ecumencial council at Constantinople to fix the schism between East and West on the basis of Nicean orthodoxy.[5] "The council went on to define orthodoxy, including the mysterious Third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Ghost who, though equal to the Father, 'proceeded' from Him, whereas the Son was 'begotten' of Him.[6] The council also "condemned the Apollonian and Macedonian heresies, clarified church jurisdictions according to the civil boundaries of dioceses and ruled that Constantinople was second in precedence to Rome."[6]

With the death of Valens, the Arians' protector, his defeat probably damaged the standing of the Homoian faction.

In imperial matters, Theodosius oversaw the raising in 390 C.E. of the Egyptian obelisk from Karnak. As Imperial spoils, it still stands in the Hippodrome, the long racetrack that was the center of Constantinople's public life and scene of political turmoil. Re-erecting the monolith was a challenge for the technology that had been honed in siege engines. The obelisk, still recognizably a solar symbol, was removed to Alexandria in the first flush of Christian triumphalism at mid-century, but then spent a generation lying at the docks while people figured how to ship it to Constantinople, and was cracked in transit nevertheless. The white marble base is entirely covered with bas-reliefs documenting the Imperial household and the engineering feat itself. Theodosius and the imperial family are separated from the nobles among the spectators in the Imperial box with a cover over them as a mark of their status. The naturalism of the Roman tradition in such scenes is giving way to a conceptual art: the idea of order, decorum and respective ranking, expressed in serried ranks of faces, is beginning to oust the mere transitory details of this life, celebrated in Pagan portraiture. Christianity had only just been appointed the new state religion.

Pagan conflicts during the reign of Theodosius I

On May 15, 392 C.E., Valentinian II was found hanged in his residence in the town of Vienne in Gaul. The Frankish soldier and Pagan Arbogast, Valentinian's protector and magister militum, maintained that it was suicide. Arbogast and Valentinian had frequently disputed rulership over the Western Roman Empire, and Valentinian was also noted to have complained of Arbogast's control over him to Theodosius. Thus when word of his death reached Constantinople Theodosius believed, or at least suspected, that Arbogast was lying and that he had engineered Valentinian's demise. These suspicions were further fueled by Arbogast's elevation of a Eugenius, pagan official to the position of Western Emperor, and the veiled accusations that Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, spoke during his funeral oration for Valentinian.

Valentinian II's death sparked a civil war between Eugenius and Theodosius over the rulership of the west in the Battle of the Frigidus. The resultant eastern victory there led to the final brief unification of the Roman Empire under Theodosius, and the ultimate irreparable division of the empire after his death.

Proscription of Paganism

For the first part of his rule, Theodosius seems to have ignored the semi-official standing of the Christian bishops; in fact he had voiced his support for the preservation of temples or Pagan statues as useful public buildings. In his early reign, Theodosius was fairly tolerant of the pagans, for he needed the support of the influential pagan ruling class. However he would in time stamp out the last vestiges of paganism with great severity.[7] His first attempt to inhibit paganism was in 381 when he reiterated Constantine's ban on sacrifice. However, for the most part in his early reign he was very tolerant on pagans in the Empire.

In 388 C.E., he sent a prefect to Syria, Egypt, and Asia Minor with the aim of breaking up pagan associations and the destruction of their temples. The Serapeum at Alexandria was destroyed during this campaign.[8] In a series of decrees called the "Theodosian decrees" he progressively declared that those Pagan feasts that had not yet been rendered Christian ones were now to be workdays (in 389). In 391 C.E., he reiterated the ban of blood sacrifice and decreed "no one is to go to the sanctuaries, walk through the temples, or raise his eyes to statues created by the labor of man."[9] The temples that were thus closed could be declared "abandoned," as Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria immediately noted in applying for permission to demolish a site and cover it with a Christian church, an act that must have received general sanction, for mithraea forming crypts of churches, and temples forming the foundations of fifth-century churches appear throughout the former Roman Empire. Theodosius participated in actions by Christians against major Pagan sites: the destruction of the gigantic Serapeum of Alexandria and its library by a mob in around 392 C.E., according to the Christian sources authorized by Theodosius (extirpium malum), needs to be seen against a complicated background of less spectacular violence in the city:[10] Eusebius mentions street-fighting in Alexandria between Christians and non-Christians as early as 249 C.E., and non-Christians had participated in the struggles for and against Athanasius in 341 C.E. and 356 C.E. "In 363 they killed Bishop George for repeated acts of pointed outrage, insult, and pillage of the most sacred treasures of the city."[11]

By decree in 391 C.E., Theodosius ended the official finds that had still trickled to some remnants of Greco-Roman civic Paganism too. The eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum was extinguished, and the Vestal Virgins were disbanded. Taking the auspices and practicing witchcraft were to be punished. Pagan members of the Senate in Rome appealed to him to restore the Altar of Victory in the Senate House; he refused. After the last Olympic Games in 393 C.E., Theodosius cancelled the games, and the reckoning of dates by Olympiads soon came to an end. Now Theodosius portrayed himself on his coins holding the labarum.

The apparent change of policy that resulted in the "Theodosian decrees" has often been credited to the increased influence of Ambrose, bishop of Milan. It is worth noting that in 390 C.E. Ambrose had excommunicated Theodosius, who had recently ordered the massacre of 7,000 inhabitants of Thessalonica,[12] in response to the assassination of his military governor stationed in the city, and that Theodosius performed several months of public penance. The specifics of the decrees were superficially limited in scope, specific measures in response to various petitions from Christians throughout his administration.

Death

Theodosius died, after battling the vascular disease oedema, in Milan on January 17, 395 C.E. Ambrose organized and managed Theodosius's lying state in Milan. Ambrose delivered a panegyric titled De Obitu Theodosii[13] before Stilicho and Honorius in which Ambrose detailed the suppression of heresy and paganism by Theodosius. Theodosius was finally laid to rest in Constantinople on November 8, 395 C.E.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Stephen Williams and Gerard Friell, Theodosius: The Empire at Bay (Yale University Press, 1994), 34.

- ↑ Williams and Friell, p. 64.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Williams and Friell, p. 129.

- ↑ Williams and Friell, p. 134.

- ↑ Williams and Friell, p. 54.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Williams and Friell, p. 55.

- ↑ "Theodosius I," Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912 Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Socr., V, 16

- ↑ Michael Routery, 1997, The First Missionary War. The Church take over of the Roman Empire, Ch. 4, The Serapeum of Alexandria Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Michael Routery, 1997, cit. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Ramsay McMullan, Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D. 100-400 (Yale University Press, 1984, 90.

- ↑ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 112.

- ↑ Williams and Friell, p. 139

- ↑ Williams and Friell, p. 140.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hodgkin, Thomas. The Dynasty Of Theodosius: Or Eighty Years' Struggle With The Barbarians. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 978-0548239995

- Lenski, Noel. Failure of Empire. University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0-520-23332-8

- McMullan, Ramsay. Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D. 100-400. Yale University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0300036428

- Norwich, J. Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 978-0394537788112

- Williams, Stephen, and J. G. P. Friell. Theodosius The Empire at Bay. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780300061734

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.