Toraja

| Toraja |

|---|

| Young Toraja girls at a wedding ceremony. |

| Total population |

| 650,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| West Sulawesi, South Sulawesi |

| Languages |

| Toraja-Sa'dan, Kalumpang, Mamasa, Ta'e, Talondo', and Toala'. |

| Religions |

| Protestant Christian 69.14%, Roman Catholic 16.97%), Islam (Sunni) 7.89%, and Hinduism (Aluk To Dolo) 5.99%. |

The Toraja (meaning "people of the uplands") are an ethnic group indigenous to a mountainous region of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The majority still live in the regency of Tana Toraja ("Land of Toraja"). Most of the population is Christian, and others are Muslim or have local animist beliefs known as aluk ("the way"). The Indonesian government has recognized this animist belief as Aluk To Dolo ("Way of the Ancestors").

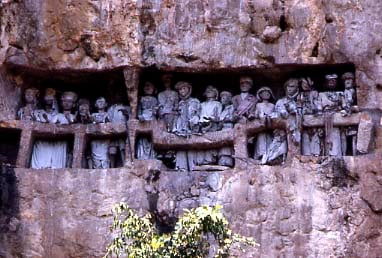

Torajans are renowned for their elaborate funeral rites, burial sites carved into rocky cliffs, massive peaked-roof traditional houses known as tongkonan, and colorful wood carvings. Toraja funeral rites are important social events, usually attended by hundreds of people and lasting for several days.

Before the twentieth century, Torajans lived in autonomous villages, where they practiced animism and were relatively untouched by the outside world. In the early 1900s, Dutch missionaries first worked to convert Torajan highlanders to Christianity. When the Tana Toraja regency was further opened to the outside world in the 1970s, it became an icon of tourism in Indonesia: it was exploited by tourism developers and studied by anthropologists. By the 1990s, when tourism peaked, Toraja society had changed significantly, from an agrarian model — in which social life and customs were outgrowths of the Aluk To Dolo—to a largely Christian society. The challenge for Toraja people today is to find their place in the world, a world that they maintained a fierce separatism from for centuries and have only recently come to embrace. Indonesia as a whole faces problems of poverty, illiteracy, and political instability making Torajan inclusion of doubtful success. Yet, to rely on tourism requires the Toraja people to continue to practice their rituals with external enthusiasm, putting on a show for those who do not believe as they do. To find their true place, Toraja must reconcile their internal beliefs with the developments of the world, both external and internal, and be embraced as true members of the family of humankind.

Ethnic identity

The Torajan people had little notion of themselves as a distinct ethnic group before the twentieth century. Before Dutch colonization and Christianization, Torajans, who lived in highland areas, identified with their villages and did not share a broad sense of identity. Although complexes of rituals created linkages between highland villages, there were variations in dialects, differences in social hierarchies, and an array of ritual practices in the Sulawesi highland region.

In 1909, the Dutch colonial government named the people Toraja, from the language of the coastal people, the Bugis, to meaning people and riaja, uplands. It was first used as a lowlander expression for highlanders.[1] As a result, "Toraja" initially had more currency with outsiders—such as the Bugis and Makassarese, who constitute a majority of the lowland of Sulawesi—than with insiders. The Dutch missionaries' presence in the highlands gave rise to the Toraja ethnic consciousness in the Sa'dan Toraja region, and this shared identity grew with the rise of tourism in the Tana Toraja Regency.[2]

History

The Gulf of Tonkin, lying between northern Vietnam and southern China, is believed to be the origin of the Torajans.[3] There has been a long acculturation process of local Malay people in Sulawesi with these Chinese immigrants. At first, the immigrants lived along Sulawesi's coastal areas, near Enrekang Bay, but subsequently moved upland.

From the seventeenth century, the Dutch established trade and political control on Sulawesi through the Dutch East Indies Company. Over two centuries, they ignored the mountainous area in the central Sulawesi, where Torajans lived, because access was difficult and it had little productive agricultural land. In the late nineteenth century, the Dutch became increasingly concerned about the spread of Islam in the south of Sulawesi, especially among the Makassarese and Bugis peoples. The Dutch saw the animist highlanders as potential Christians. In the 1920s, the Reformed Missionary Alliance of the Dutch Reformed Church began missionary work aided by the Dutch colonial government.[4]

In addition to introducing Christianity, the Dutch abolished slavery and imposed local taxes. A line was drawn around the Sa'dan area and called Tana Toraja ("the land of Toraja"). In 1946, the Dutch granted Tana Toraja a regentschap, and it was recognized in 1957 as one of the regencies of Indonesia.[4]

Early Dutch missionaries faced strong opposition among Torajans, especially among the elite, angered by the abolition of their profitable slave trade.[5] Some Torajans were forcibly relocated to the lowlands by the Dutch, where they could be more easily controlled. Taxes were kept high, undermining the wealth of the elites. Ultimately, the Dutch influence did not subdue Torajan culture, and only a few Torajans were converted.[6]

Then, Muslim lowlanders attacked the Torajans, resulting in widespread Christian conversion among those who sought to align themselves with the Dutch for political protection and to form a movement against the Bugis and Makassarese Muslims. Between 1951 and 1965 (following Indonesian independence), southern Sulawesi faced a turbulent period as the Darul Islam separatist movement fought for an Islamic state in Sulawesi. The 15 years of guerrilla warfare led to massive conversions to Christianity.[7]

Alignment with the Indonesian government, however, did not guarantee safety for the Torajans. In 1965, a presidential decree required every Indonesian citizen to belong to one of five officially recognized religions: Islam, Christianity (Protestantism and Catholicism), Hinduism, or Buddhism. The Torajan religious belief (aluk) was not legally recognized, and the Torajans raised their voices against the law. To make aluk accord with the law, it had to be accepted as part of one of the official religions. In 1969, Aluk To Dolo ("the way of ancestors") was legalized as a sect of Agama Hindu Dharma, the official name of Hinduism in Indonesia.[4]

Society

There are three main types of affiliation in Toraja society: family, class and religion.

Family affiliation

Family is the primary social and political grouping in Torajan society. Each village is one extended family, the seat of which is the tongkonan, a traditional Torajan house. Each tongkonan has a name, which becomes the name of the village. The familial dons maintain village unity. Each person belongs to both the mother's and the father's families, the only bilateral family line in Indonesia.[8] Children, therefore, inherit household affiliation from both mother and father, including land and even family debts. Children's names are given on the basis of kinship, and are usually chosen after dead relatives. Names of aunts, uncles, and cousins are commonly referred to in the names of mothers, fathers, and siblings.

Marriage between distant cousins (fourth cousins and beyond) is a common practice that strengthens kinship. Toraja society prohibits marriage between close cousins (up to and including the third cousin)—except for nobles, to prevent the dispersal of property.[9] Kinship is actively reciprocal, meaning that the extended family helps each other farm, share buffalo rituals, and pay off debts.

In a more complex situation, in which one Toraja family could not handle their problems alone, several villages formed a group; sometimes, villages would unite against other villages. Relationship between families was expressed through blood, marriage, and shared ancestral houses (tongkonan), practically signed by the exchange of buffalo and pigs on ritual occasions. Such exchanges not only built political and cultural ties between families but defined each person's place in a social hierarchy: who poured palm wine, who wrapped a corpse and prepared offerings, where each person could or could not sit, what dishes should be used or avoided, and even what piece of meat constituted one's share.[10]

Class affiliation

In early Toraja society, family relationships were tied closely to social class. There were three strata: nobles, commoners, and slaves (until slavery was abolished in 1909 by the Dutch East Indies government). Class was inherited through the mother. It was taboo, therefore, to marry "down" with a woman of lower class. On the other hand, marrying a woman of higher class could improve the status of the next generation. The nobility's condescending attitude toward the commoners is still maintained today for reasons of family prestige.[11]

Nobles, who were believed to be direct descendants of the descended person from heaven,[12] lived in tongkonans, while commoners lived in less lavish houses (bamboo shacks called banua). Slaves lived in small huts, which had to be built around their owner's tongkonan. Commoners might marry anyone, but nobles preferred to marry in-family to maintain their status. Sometimes nobles married Bugis or Makassarese nobles. Commoners and slaves were prohibited from having death feasts. Despite close kinship and status inheritance, there was some social mobility, as marriage or change in wealth could affect an individual's status.[9] Wealth was counted by the ownership of water buffaloes.

Slaves in Toraja society were family property. Sometimes Torajans decided to become slaves when they incurred a debt, pledging to work as payment. Slaves could be taken during wars, and slave trading was common. Slaves could buy their freedom, but their children still inherited slave status. Slaves were prohibited from wearing bronze or gold, carving their houses, eating from the same dishes as their owners, or having sex with free women—a crime punishable by death.

Religious affiliation

Toraja's indigenous belief system is polytheistic animism, called aluk, or "the way" (sometimes translated as "the law"). The earthly authority, whose words and actions should be cleaved to both in life (agriculture) and death (funerals), is called to minaa (an aluk priest). Aluk is not just a belief system; it is a combination of law, religion, and habit. Aluk governs social life, agricultural practices, and ancestral rituals. The details of aluk may vary from one village to another.

In the Toraja myth, the ancestors of Torajan people came down from heaven using stairs, which were then used by the Torajans as a communication medium with Puang Matua, the Creator. The cosmos, according to aluk, is divided into the upper world (heaven), the world of man (earth), and the underworld.[5] At first, heaven and earth were married, then there was a darkness, a separation, and finally the light. Animals live in the underworld, which is represented by rectangular space enclosed by pillars, the earth is for humankind, and the heaven world is located above, covered with a saddle-shaped roof.

The role of human beings is to help maintain equilibrium between the heaven world and the underworld by means of rituals, of which there are two divisions. The Rambu Tuka (Rising Sun or Smoke Ascending) rituals are associated with the north and east, with joy and life, and include rituals for birth, marriage, health, the house, the community, and rice. Fertility The Rambu Solo (Setting Sun or Smoke Descending) rituals are associated with the south and west, with darkness, night, and death. Healing rituals partake of both divisions. Rambu Solo rituals include great death feasts at funerals conducted by the death priest. Display of wealth is important for Torajans believe they will live in the afterworld as they do on earth, and the souls of sacrificed animals will follow their masters to heaven. These funerals are now the main feature of Toraja religion.[13]

The afterworld is Puya, "the land of souls," which is to the southwest under the earth. According to Toraja belief, by a lavish death feast the deceased will reach Puya. He is judged by Pong Lalondong ("the lord who is a cock," who judges the dead) and then climbs a mountain to reach heaven, where he joins the deified ancestors as a constellation which guards humankind and the rice.

One common law is the requirement that death and life rituals be separated. Torajans believe that performing death rituals might ruin their corpses if combined with life rituals. The two types of ritual were equally important. However, during the time of the Dutch missionaries, Christian Torajans were prohibited from attending or performing life rituals which are primarily associated with fertility, but were allowed to perform death rituals as funerals were acceptable.[6] Consequently, Toraja's death rituals are still practiced today, while life rituals have diminished. With the advent of tourism and development of the area in the late twentieth century, the Toraja have further refined their belief system to focus primarily on attending the deities of heaven, with little use for those relating to the earth and physical life.

Culture

Tongkonan

Tongkonan are the traditional Torajan ancestral houses. They stand high on wooden piles, topped with a layered split-bamboo roof shaped in a sweeping curved arc, and they are incised with red, black, and yellow detailed wood carvings on the exterior walls. The word "tongkonan" comes from the Torajan tongkon ("to sit").

According to Torajan myth, the first tongkonan was built in heaven on four poles, with a roof made of Indian cloth. When the first Torajan ancestor descended to earth, he imitated the house and held a large ceremony.[14]

Tongkonan are the center of Torajan social life. The rituals associated with the tongkonan are important expressions of Torajan spiritual life, and therefore all family members are impelled to participate, because symbolically the tongkonan represents links to their ancestors and to living and future kin.[10]

The construction of a tongkonan is laborious work and is usually done with the help of the extended family. There are three types of tongkonan. The tongkonan layuk is the house of the highest authority, used as the "center of government." The tongkonan pekamberan belongs to the family members who have some authority in local traditions. Ordinary family members reside in the tongkonan batu. The exclusivity to the nobility of the tongkonan is diminishing as many Torajan commoners find lucrative employment in other parts of Indonesia. As they send back money to their families, they enable the construction of larger tongkonan.

Wood carvings

To express social and religious concepts, Torajans carve wood, calling it Pa'ssura (or "the writing"). Wood carvings are therefore Toraja's cultural manifestation.[15]

Each carving receives a special name, and common motifs are animals and plants that symbolize some virtue. For example, water plants and animals, such as crabs, tadpoles and water weeds, are commonly found to symbolize fertility.

Regularity and order are common features in Toraja wood carving, as well as abstracts and geometrical designs. Nature is frequently used as the basis of Toraja's ornaments, because nature is full of abstractions and geometries with regularities and ordering.

| Some Toraja patterns | |||

Funeral rites

There is a belief in Toraja that when you die you won't be separated directly from the family - you are expected to bring them good luck and so the family must respect you. When we think of our ancestors, we respect them as individuals, rather than as a group. When a small baby dies, one who hasn't grown teeth yet, they used to be buried in a tree. It had to be a living tree, so that as the tree grew it continued the baby's life.[16]

In Toraja society the funeral ritual is the most elaborate and expensive event. The richer and more powerful the individual, the more expensive is the funeral. In the aluk religion, only nobles have the right to have an extensive death feast.[17] The death feast of a nobleman is usually attended by thousands and lasts for several days. A ceremonial site, called rante, is usually prepared in a large, grassy field where shelters for audiences, rice barns, and other ceremonial funeral structures are specially made by the deceased family. Flute music, funeral chants, songs, and poems, and crying and wailing are traditional Toraja expressions of grief with the exceptions of funerals for young children, and poor, low-status adults.[18]

The ceremony is often held weeks, months, or years after the death so that the deceased's family can raise the significant funds needed to cover funeral expenses. For example, in 1992, the most powerful Torajan, the former chief of Tana Toraja Regency, died, and his family asked US$125,000 of a Japanese TV company as a license fee to film the funeral.[19] During the waiting period, the body of the deceased is wrapped in several layers of cloth and kept under the tongkonan Torajans traditionally believe that death is not a sudden, abrupt event, but a gradual process toward Puya (the land of souls, or afterlife). The soul of the deceased is thought to linger around the village until the funeral ceremony is completed, after which it begins its journey to Puya.[20]

Another component of the ritual is the slaughter of water buffalo. The more powerful the person who died, the more buffalo are slaughtered at the death feast. Buffalo carcasses, including their heads, are usually lined up on a field waiting for their owner, who is in the "sleeping stage." Torajans believe that the deceased will need the buffalo to make the journey and that they will arrive more quickly at Puya if they have many buffalo. Slaughtering tens of water buffalo and hundreds of pigs using a machete is the climax of the elaborate death feast, with dancing and music and young boys who catch spurting blood in long bamboo tubes. Some of the slaughtered animals are given by guests as "gifts," which are carefully noted because they will be considered debts of the deceased's family.[19]

The final resting place of the dead is the liang, a tomb usually located high on a cliff safe from thieves, since the deceased's wealth is buried with him. There are three methods of burial: the coffin may be laid in a cave, or in a carved stone grave, or hung on a cliff. It contains any possessions that the deceased will need in the afterlife. The wealthy are often buried in a stone grave carved out of a rocky cliff. The grave is usually expensive and takes a few months to complete. In some areas, a stone cave may be found that is large enough to accommodate a whole family. A wood-carved effigy, called tau tau, is usually placed in the cave looking out over the land. The coffin of a baby or child may be hung from ropes on a cliff face or from a tree. This hanging grave usually lasts for years, until the ropes rot and the coffin falls to the ground.

Dance and music

Torajans perform dances on various occasions. The aluk religion governs when and how Torajans dance. Ma'bua is a major Toraja ceremony in which priests wear a buffalo head and dance around a sacred tree. This dance can be performed only once every 12 years.

Dance is very important during their elaborate funeral ceremonies. They dance to express their grief, and to honor and even cheer the deceased person because he is going to have a long journey in the afterlife. First, a group of men form a circle and sing a monotonous chant throughout the night to honor the deceased (a ritual called Ma'badong).[19] This is considered by many Torajans to be the most important component of the funeral ceremony.[18] On the second funeral day, the Ma'randing warrior dance is performed to praise the courage of the deceased during life. Several men perform the dance with a sword, a large shield made from buffalo skin, a helmet with a buffalo horn, and other ornamentation. The Ma'randing dance precedes a procession in which the deceased is carried from a rice barn to the rante, the site of the funeral ceremony. During the funeral, elder women perform the Ma'katia dance while singing a poetic song and wearing a long feathered costume. The Ma'akatia dance is performed to remind the audience of the generosity and loyalty of the deceased person. After the bloody ceremony of buffalo and pig slaughter, a group of boys and girls clap their hands while performing a cheerful dance called Ma'dondan.

As in other agricultural societies, Torajans dance and sing during harvest time. The Ma'bugi dance celebrates the thanksgiving event, and the Ma'gandangi dance is performed while Torajans are pounding rice.[21] There are several war dances, such as the Manimbong dance performed by men, followed by the Ma'dandan dance performed by women.

A traditional musical instrument of the Toraja is a bamboo flute called a Pa'suling (suling is an Indonesian word for flute). This six-holed flute (not unique to the Toraja) is played at many dances, such as the thanksgiving dance Ma'bondensan, where the flute accompanies a group of shirtless, dancing men with long fingernails. The Toraja also have indigenous musical instruments, such as the Pa'pelle (made from palm leaves) and the Pa'karombi (the Torajan version of a Jew's harp). The Pa'pelle is played during harvest time and at house inauguration ceremonies.[21]

Language

Language varieties of Toraja, including Kalumpang, Mamasa, Tae', Talondo', Toala', and Toraja-Sa'dan, belong to the Malayo-Polynesian language from the Austronesian family.[22] At the outset, the isolated geographical nature of Tana Toraja led to the formation of many dialects among the Toraja languages. Although the national Indonesian language is the official language and is spoken in the community, all elementary schools in Tana Toraja teach Toraja language.

A prominent attribute of Toraja language is the notion of grief. The importance of death ceremony in Toraja culture has characterized their languages to express intricate degrees of grief and mourning.[18] The Toraja language contains many terms referring sadness, longing, depression, and mental pain. It is a catharsis to give a clear notion about psychological and physical effect of loss, and sometimes to lessen the pain of grief itself.

Economy

Prior to Suharto's "New Order" administration, the Torajan economy was based on agriculture, with cultivated wet rice in terraced fields on mountain slopes, and supplemental cassava and maize crops. Much time and energy were devoted to raising water buffalo, pigs, and chickens, primarily for ceremonial sacrifices and consumption.[7] The only agricultural industry in Toraja was a Japanese coffee factory, Kopi Toraja.

With the commencement of the New Order in 1965, Indonesia's economy developed and opened to foreign investment. Multinational oil and mining companies opened new operations in Indonesia. Torajans, particularly younger ones, relocated to work for the foreign companies—to Kalimantan for timber and oil, to Papua for mining, and to the cities of Sulawesi and Java. The out-migration of Torajans was steady until 1985.[4]

The Torajan economy gradually shifted to tourism beginning in 1984. Between 1984 and 1997, many Torajans obtained their incomes from tourism, working in hotels, as tour guides, or selling souvenirs. With the rise of political and economic instability in Indonesia in the late 1990s—including religious conflicts elsewhere on Sulawesi—tourism in Tana Toraja declined dramatically.

Contemporary Toraja

Before the 1970s, Toraja was almost unknown to Western tourism. In 1971, about 50 Europeans visited Tana Toraja. In 1972, at least 400 visitors attended the funeral ritual of Puang of Sangalla, the highest-ranking nobleman in Tana Toraja and the last pure-blooded Toraja noble. The event was documented by National Geographic and broadcast in several European countries.[4] In 1976, about 12,000 tourists visited the regency and in 1981, Torajan sculpture was exhibited in major North American museums.[23] "The land of the heavenly kings of Tana Toraja," as written in the exhibition brochure, embraced the outside world.

In 1984, the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism declared Tana Toraja Regency the prima donna of South Sulawesi. Tana Toraja was heralded as "the second stop after Bali."[11] Tourism developers marketed Tana Toraja as an exotic adventure—an area rich in culture and off the beaten track. Toraja was for tourists who had gone as far as Bali and were willing to see more of the wild, "untouched" islands. Western tourists expected to see stone-age villages and pagan funerals. However, they were more likely to see a Torajan wearing a hat and denim, living in a Christian society.[4]

A clash between local Torajan leaders and the South Sulawesi provincial government broke out in 1985 when the government designated 18 Toraja villages and burial sites as traditional "touristic objects." Consequently, zoning restrictions were applied to these areas, such that Torajans themselves were barred from changing their tongkonans and burial sites. The plan was opposed by some Torajan leaders, as they felt that their rituals and traditions were being determined by outsiders. As a result, in 1987, the Torajan village of Kété Kesú and several other designated "tourist objects" closed their doors to tourists. This closure lasted only a few days, as the villagers found it too difficult to survive without the income from selling souvenirs.[2]

Tourism has transformed Toraja society. Originally, there was a ritual which allowed commoners to marry nobles (puang) and thereby gain nobility for their children. However, the image of Torajan society created for the tourists, often by "lower-ranking" guides, has eroded its traditional strict hierarchy.[11] High status is not as esteemed in Tana Toraja as it once was. Many low-ranking men can declare themselves and their children nobles by gaining enough wealth through work outside the region and then marrying a noble woman.

Notes

- ↑ Hetty Nooy-Palm, "Introduction to the Sa'dan People and their Country." Archipel 15 (1975): 163—192.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kathleen M. Adams, "Cultural Commoditization in Tana Toraja, Indonesia" Cultural Survival Quarterly (March 1990). Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ A.C. Kruyt, De West-Toradjas op Midden-Celebes (Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers-Maatschappij, 1938).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Toby Alice Volkman, "Visions and Revisions: Toraja Culture and the Tourist Gaze" American Ethnologist 17 (February 1990): 91–110.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jowa Imre Kis-Jovak, Banua Toraja: Changing Patterns in Architecture and Symbolism among the Sa’dan Toraja, Sulawesi, Indonesia (Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, 1998, ISBN 9068322079).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zakaria J. Ngelow, "Traditional Culture, Christianity and Globalization in Indonesia: The Case of Torajan Christians" Inter-Religio 45 (Summer 2004) Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Toby Alice Volkman, "A View from the Mountains" Cultural Survival Quarterly (December 1983). Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Roxana Waterson, "Houses, graves and the limits of kinship groupings among the Sa’dan Toraja." Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 151(2) (1995): 194–217. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Roxana Waterson, "The ideology and terminology of kinship among the Sa’dan Toraja" Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 142(1) (1986): 87–112. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Toby Alice Volkman, "Great Performances: Toraja Cultural Identity in the 1970s." American Ethnologist 11 (1) (February 1984).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kathleen M. Adams, "Making-Up the Toraja? The Appropriate of Tourism, Anthropology, and Museums for Politics in Upland Sulawesi, Indonesia" Ethnology 34(2) (Spring 1995):143.

- ↑ Jane C. Wellenkamp, "Order and Disorder in Toraja Thought and Ritual" Ethnology 27(3) (1988):311-326

- ↑ "Toraja Religion" Overview of World Religion Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Tongkonan: Torajan Kindred Houses Architecture-Tongkonan. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Rizal Muslimin, "Toraja Glyphs: An Ethnocomputation Study of Passura Indigenous Icons" Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering (1) (2017): 39-44. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Nicolaus Pasassung, Burial - Toraja, Sulawesi Australian Museum. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ In the present day, when tourism is the main income of the Torajans, funeral feasts have been held by non-noble rich families, mainly performed as tourist attractions.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Jane C. Wellenkamp, "Notions of Grief and Catharsis among the Toraja." American Ethnologist 15(3) (1988): 486—500. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Shinji Yamashita, "Manipulating Ethnic Tradition: The Funeral Ceremony, Tourism, and Television among the Toraja of Sulawesi" Indonesia 58 (October 1994): 69—82.

- ↑ Douglas Hollan, "To the Afterworld and Back: Mourning and Dreams of the Dead among the Toraja" Ethos 23(4) (December 1995): 424–436.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Types of Dance and music in Tana Toraja Kharisma Toraja. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Toraja-Sa’dan Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ↑ Toby Volkman, "Tana toraja: A Decade of Tourism" Cultural Survival Quarterly (September 1982). Retrieved January 9, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Kathleen M. Art as Politics: Re-crafting Identities, Tourism and Power in Tana Toraja, Indonesia. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0824830724

- Bigalke, Terance. Tana Toraja: A Social History of an Indonesian People. Singapore: KITLV Press, 2005. ISBN 9971693186

- Buijs, Kees. Powers of Blessing from the Wilderness and from Heaven: Structure and Transformations in the Religion of the Toraja in the Mamasa Area of South Sulawesi. Singapore: Kitlv Press, 2007. ISBN 978-9067182706

- Hollan, Douglas W., and Jane C. Wellenkamp. The Thread of Life: Toraja Reflections on the Life Cycle. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1996. ISBN 0824818393

- Kis-Jovak, Jowa Imre. Banua Toraja : Changing Patterns in Architecture and Symbolism among the Sa’dan Toraja, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, 1998. ISBN 9068322079

- Kruyt, A.C. De West-Toradjas op Midden-Celebes. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers-Maatschappij, 1938.

- Nooy-Palm, Hetty. The Sa'dan-Toraja: A Study of Their Social Life and Religion. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1988. ISBN 9024722748

- Parinding, Samban C., and Judi Achjadi. Toraja: Indonesia's Mountain Eden. Singapore: Time Edition, 1988. ISBN 9812040161

- Volkman, Toby Alice. Feasts of Honor: Ritual and Change in the Toraja Highland. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0252011832

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.