| American Civil War | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 1861â1865 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Place | Principally in the Southern United States; also in Eastern, Central, and Southwestern United States | ||||||||||||||||||

| Result | Defeat of seceding CSA | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The watershed event of United States history was the American Civil War (1861â1865), fought in North America within the territory of the United States of America, between 24 mostly northern states of the Union and the Confederate States of America, a coalition of eleven southern states that declared their independence and claimed the right of secession from the Union in 1860â1861. The war produced more than 970,000 casualties (3.09 percent of the population), which included approximately 560,300 deaths (1.78 percent), a loss of more American lives than any other conflict in history. Its protagonists on both sides, Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee, were men of exceptional character and among the most storied figures in American history.

The Union victory resulted in the abolition of slavery and consolidation of the Union. Yet full equality for African Americans would wait another century, until the fruits of the Civil Rights Movement. For good or ill, preservation of the Union enabled the United States to emerge as a major world power in the closing years of the nineteenth century. Had a Confederate victory split the union, and the United States not achieved its resulting productivity, military capability, and wealth, twentieth-century history would have looked very different.

Debate on what was the main cause of the Civil War continues. There were issues of states' rights versus the federal government, tariffs that unfairly impacted the South, and the North's burgeoning industrial economy which disadvantaged the South with its dependence on agriculture. The South chafed under high export tariffs imposed by the federal government which made the northern textile mills the only viable market for its cottonâfor which they set an unrealistically low price. That demand required an inexpensive and plentiful labor force, which slaves afforded.

Nevertheless, the root cause was slavery itself. The young American Republic, founded on the ideals of democratic rights, had failed to address the slavery issue within a twenty-year period following the ratification of the United States Constitution (1789), as the Founders had stipulated at the Constitutional Convention. Outwardly the issue was balancing federal and states' rights, an issue of great importance to the Founders as evidenced by the acceptance of the Connecticut Compromise (1787). On this score, the South's secession from the Union in 1861 was clearly in violation of the Constitution. The only constitutionally acceptable way for a State to withdraw from the Union was either through a constitutional amendment or through a Constitutional Convention that would have required the support of three fourths of the States. However, internally the issue was slavery. From the beginning, the Federalist papers and Anti-Federalist papers as well as the Constitution itself with its Three-Fifths Compromise made it clear that slavery was more than just a State concern.

The Civil War occurred even though President Lincoln had stressed that he was prepared to accommodate slavery for the sake of the Union. Following the outbreak of the Civil War he came to regret that he had taken this position in contradiction to his moral principles. He later publicly repented for this position. In his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865 he suggested that the Civil War was the way in which America had to indemnify its sin of accommodating slavery. He speculated that the bloody American Civil War would not end until "until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword." The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 would be followed by other significant civil rights developments such as President Truman's Executive Order 9981 ending segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces (1948); the Supreme Court ruling in Brown versus Board of Education (1954) overturning the "separate but equal" clause and ending segregation in public schools; the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1957); the U.S. Civil Rights Act (1964); the U.S. Voting Rights Act (1965); the Supreme Court Ruling in Loving vs. Virginia Supreme Court allowing for interracial marriage (1967). These steps towards racial harmony were all necessary corrections in order to prepare the United States legislatively, judicially, socially and attitudinally to reflect its founding ideals on the world stage and advance towards becoming an exemplary nation of the global community.

Prelude to War

In 1818, the Missouri Territory applied for statehood as a slave state. Thomas Jefferson wrote at the time that the, "momentous question, like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror." The resulting Missouri compromise prevented the split between the states for a time as it allowed Missouri to enter the union as a slave state and Maine to simultaneously join as a free state. Although Americans hoped the dispute over slavery was settled, John Quincy Adams called the compromise "a title page to a great tragic volume."

The aftermath of the Mexican-American War proved Adams right. The immense territory awarded the United States, emerging from the war victorious, included the territory that would become Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. A Pennsylvania congressman, David Wilmot, was determined to keep the newly annexed territory free. He introduced a bill called the Wilmot Proviso that disallowed slavery in any part of the territory. The bill did not pass but laid the ground work for another compromise.

The Compromise of 1850 was hammered out by the great orators of the time. Senators Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, and Henry Clay from the border state Kentucky delivered a compromise that once again had Americans believing war had been averted. Under the terms of The Compromise of 1850, California was admitted as a free state, Texas as a slave state, and New Mexico and Utah would choose their own destinies depending upon the will of their citizens. Slave trade was abolished within the District of Columbia. The compromise also strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act.

Yet the terms of the compromise turned out to be self-defeating. Because of the Fugitive Slave Act, the manhunts for runaway slaves became daily fare in the streets of cities and towns across the country. Northern Abolitionists became further outraged by slavery, some breaking runaways out from prison. The Underground Railroad rapidly rose in popularity as a method of protest in the northern states during the 1850s. The Abolitionist Movement took root. Graphic portrayals of the suffering of slaves by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her book Uncle Tom's Cabin helped sway Northern public opinion strongly against slavery. Abolitionism reached its peak when John Brown seized the armory at Harpers Ferry in Maryland.

Meanwhile, Southerners saw themselves as enslaved by the tariffs imposed by the Northern-backed federal government, and compared their rebellion with that of the 13 colonies against British tyranny. For them, the Abolitionist movement threatened their livelihood (which depended on cheap labor to harvest cotton) and way of life.

These differences resulted in a fratricidal war in which brother fought against brother and those who fought on both sides included lawyers, doctors, farmers, laborersâordinary people not just professional soldiersâand the war was lethal and bloody. What motivated such family rifts continues to animate discussion and debate. Some did see the war as a holy cause; McPherson (1995) cites such phrases as "the holy cause of Southern freedom,â "duty to one's country," "death before Yankee rule," and "bursting the bonds of tyranny" as common slogans (12). An 1863 Northern source, cited in McPherson (1995), wrote: "We are fighting for the UnionâŠa high and noble sentiment, but after all a sentiment. They are fighting for independence and are animated by passion and hatred against invaders.⊠It makes no difference whether the cause is just or not. You can get up an amount of enthusiasm that nothing else will excite" (19).

Southern arguments used to justify slavery had widespread support and a hundred years later, almost identical arguments were still being used to support segregation. In his Pulitzer Prize winning Battle Cry of Freedom (1988, 2003), McPherson comments that for most Southerners, slavery was not regarded as the evil that "Yankee fanatics" portrayed, but as a "positive good, the basis of prosperity, peace, and white supremacy, a necessity to prevent blacks from degenerating into barbarism, crime, and poverty" (8). He suggests that by the mid-nineteenth century slavery had so polarized the country that âan eventual showdownâ between North and South was inevitable.

The division of the country

The Deep South

Seven states seceded shortly after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860; even before he was inaugurated:

- South Carolina (December 21, 1860),

- Mississippi (January 9, 1861),

- Florida (January 10, 1861),

- Alabama (January 11, 1861),

- Georgia (January 19, 1861),

- Louisiana (January 26, 1861), and

- Texas (February 1, 1861).

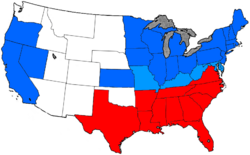

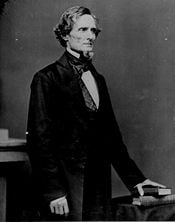

These states of the Deep South, where slavery and cotton plantations (agriculture) were most dominant, formed the Confederate States of America (C.S.A.) (February 4, 1861), with Jefferson Davis as President, and a governmental structure closely modeled on the U.S. Constitution. After the Battle of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, Lincoln called for troops from all remaining states to recover the forts, resulting in the secession of four more states: Virginia (April 17, 1861), Arkansas (May 6, 1861), North Carolina (May 20, 1861), and Tennessee (June 8, 1861).

Border States

Along with the northwestern counties of Virginia (whose residents did not wish to secede and eventually entered the Union in 1863 as West Virginia), four of the five northernmost "slave states," (Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky) did not secede, and became known as the Border States.

Delaware, which in the 1860 election had voted for Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, had few slaves and never considered secession. Maryland also voted for Breckinridge, and after the Baltimore riot of 1861 and other events had prompted a federal declaration of martial law, its legislature rejected secession (April 27, 1861). Both Missouri and Kentucky remained in the Union, but factions within each state organized "secessions" that were recognized by the C.S.A.

In Missouri, the state government under Governor Claiborne F. Jackson, a Southern sympathizer, evacuated the state capital of Jefferson City and met in exile at the town of Neosho, Missouri, adopting a secession ordinance that was recognized by the Confederacy on October 30, 1861, while the Union organized a competing state government by calling a constitutional convention that had originally been convened to vote on secession.

Although Kentucky did not secede, for a time it declared itself neutral. During a brief occupation by the Confederate Army, Southern sympathizers organized a secession convention, inaugurated a Confederate Governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy.

Residents of the northwestern counties of Virginia organized secession from Virginia, with a plan for gradual emancipation, and entered the Union in 1863 as West Virginia. Similar secessions were supported in some other areas of the Confederacy (such as eastern Tennessee), but were suppressed by declarations of martial law by the Confederacy. Conversely, the southern half of the Federal Territory of New Mexico voted to secede, and was accepted into the Confederacy as the Territory of Arizona (see map), with its capital in Mesilla (now part of New Mexico). Although the northern half of New Mexico never voted to secede, the Confederacy did lay claim to this territory and briefly occupied the territorial capital of Santa Fe between March 13 and April 8, 1862, but never organized a territorial government.

Origins of the conflict

There had been a continuing contest between the states and the national government over the power of the latter, and over the loyalty of the citizenry, almost since the founding of the republic. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, for example, had defied the Alien and Sedition Acts, and at the Hartford Convention, New England voiced its opposition to President Madison and the War of 1812.

In the Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 the United States Congress passed protective tariffs to benefit trade in the northern states. It was deemed a "Tariff of Abominations" and its provisions would have imposed a significant economic penalty on South Carolina and other southern states if left in force. South Carolina dealt with the tariffs by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within state borders. The legislature also passed laws to enforce the ordinance, including authorization for raising a military force and appropriations for arms. In response to South Carolina's threat, Congress passed a "Force Bill" and President Andrew Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers.

By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, the United States was a nation composed of five distinct regions: the Northeast, with a growing industrial and commercial economy and an increasing density of population; the Northwest, now known as the Midwest, a rapidly expanding region of free farmers where slavery had been forever prohibited under the Northwest Ordinance; the Upper South, with a settled plantation system and in some areas declining economic fortunes; the Deep South, which served as the philosophical hotbed of secessionism; and the Southwest, a booming frontier-like region with an expanding cotton economy. With two fundamentally different labor systems at their base, the economic and social changes across the nation's geographical regionsâbased on wage labor in the North and on slavery in the Southâunderlay distinct visions of society that had emerged by the mid-nineteenth century in the North and in the South.

Before the Civil War, the United States Constitution provided a basis for peaceful debate over the future of government, and had been able to regulate conflicts of interest and conflicting visions for the new, rapidly expanding nation. For many years, compromises had been made to balance the number of "free states" and "slave states" so that there would be a balance in the Senate. The last slave state admitted was Texas in 1845, with five free states admitted between 1846 and 1859. The admission of Kansas as a slave state had recently been blocked, and it was due to enter as a free state instead in 1861. The rise of mass democracy in the industrializing North, the breakdown of the old two-party system, and increasingly virulent and hostile sectional ideologies in the mid-nineteenth century made it highly unlikely, if not impossible, to bring about the gentlemanly compromises of the past such as the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 necessary to avoid crisis. Also the existence of slave labor in the South made the Northern states the preferred destination for new immigrants from Europe resulting in an increasing dominance of the North in Congress and in presidential elections, due to population size.

Sectional tensions changed in their nature and intensity rapidly during the 1850s. The United States Republican Party was established in 1854. The new party opposed the expansion of slavery in the Western territories. Although only a small share of Northerners favored measures to abolish slavery in the South, the Republicans were able to mobilize popular support among Northerners and Westerners who did not want to compete against slave labor if the system were expanded beyond the South. The Republicans won the support of many ex-Whigs and northern ex-Democrats concerned about the South's disproportionate influence in the United States Senate, Supreme Court, and the James Buchanan administration.

Meanwhile, the profitability of cotton, or "King Cotton," as it was touted, solidified the South's dependence on the plantation system and its foundation: slave labor. A small class of slave barons, especially cotton planters, dominated the politics and society of the South.

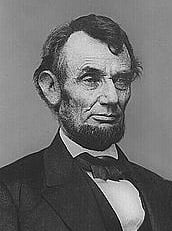

16th President (1861-1865)

Southern secession was triggered by the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was a moderate in his opposition to slavery. He pledged to do all he could to oppose the expansion of slavery into the territories (thus also preventing the admission of any additional slave states to the Union); but he also said the federal government did not have the power to abolish slavery in the states in which it already existed, and that he would enforce Fugitive Slave Laws. The southern states expected increasing hostility to their "peculiar institution"; not trusting Lincoln, and mindful that many other Republicans were intent on complete abolition of slavery. Lincoln had even encouraged abolitionists with his 1858 "House divided" speech,[1] though that speech was also consistent with an eventual end of slavery achieved gradually and voluntarily with compensation to slave-owners and resettlement of former slaves.

In addition to Lincoln's presidential victory, the slave states had lost the balance of power in the Senate and were facing a future as a perpetual minority after decades of nearly continuous control of the presidency and the Congress. Southerners also felt they could no longer prevent protectionist tariffs such as the Morrill Tariff.

The Southern justification for a unilateral right to secede cited the doctrine of states' rights, which had been debated before with the 1798 Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, and the 1832 Nullification Crisis with regard to tariffs. On the other hand, when they ratified the Constitution, each member state agreed to surrender a significant portion of its sovereignty. They accepted that a State could only withdraw from the Union either through a constitutional amendment or through a call by three fourths of the States for a Constitutional Convention, which would have rendered the extant constitution null and void. The secession from the Union by the South in 1861 was clearly in violation of the Constitution that they had ratified.

Before Lincoln took office, seven states seceded from the union, and established an independent Southern government, the Confederate States of America on February 9, 1861. They took control of federal forts and property within their boundaries, with little resistance from President Buchanan. Ironically, by seceding, the rebel states weakened any claim to the territories that were in dispute, canceled any obligation for the North to return fugitive slaves, and assured easy passage of many bills and amendments they had long opposed. The Civil War began when Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard opened fire upon Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina on April 12, 1861. There were no casualties from enemy fire in this battle.

Narrative summary

Lincoln's victory in the U.S. presidential election of 1860 triggered South Carolina's secession from the Union. Lincoln was not even on the ballot in nine states in the South. Leaders in South Carolina had long been waiting for an event that might unite the South against the anti-slavery forces. Once the election returns were certain, a special South Carolina convention declared "that the Union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states under the name of the 'United States of America' is hereby dissolved." By February 1, 1861, six more Southern states had seceded. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America and established their capital at Montgomery, Alabama. The pre-war Peace Conference of 1861 met at Washington, D.C. The remaining Southern states as yet remained in the Union. Several seceding states seized federal forts within their boundaries; President Buchanan made no military response.

Less than a month later, on March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President of the United States. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a âmore perfect unionâ than the earlier Articles of Confederation and that it was a binding contract, and called the secession "legally void." He stated he had no intent to invade Southern states, but would use force to maintain possession of federal property. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union.

The South did send delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties, but they were turned down. On April 12, the South fired upon the federal troops stationed at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina until the troops surrendered. Lincoln called for all of the states in the Union to send troops to recapture the forts and preserve the Union. Most Northerners hoped that a quick victory for the Union would crush the nascent rebellion, and so Lincoln only called for volunteers for 90 days. This resulted in four more states voting to secede. Once Virginia seceded, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond, Virginia.

Even though the Southern states had seceded, there was considerable anti-secessionist sentiment within several of the seceding states. Eastern Tennessee, in particular, was a hotbed for pro-Unionism. Winston County, Alabama issued a resolution of secession from the state of Alabama. The Red Strings were a prominent Southern anti-secession group.

Union commander, General Winfield Scott created the Anaconda Plan as the Union's main plan of attack during the war.

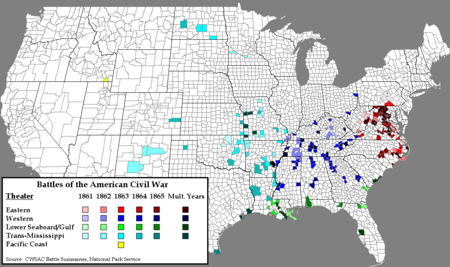

Eastern Theater 1861â1863

Because of the fierce resistance of a few initial Confederate forces at Manassas, Virginia, in July 1861, a march by Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell on the Confederate forces there was halted in the First Battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas, whereupon they were forced back to Washington, D.C. by Confederate troops under the command of Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. It was in this battle that Confederate General Thomas Jackson received the name of "Stonewall" because he stood like a stone wall against Union troops. Alarmed at the loss, and in an attempt to prevent more slave states from leaving the Union, the U.S. Congress passed the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution on July 25 of that year, which stated that the war was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end slavery.

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26 (he was briefly general-in-chief of all the Union armies, but was subsequently relieved of that post in favor of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck), and the war began in earnest in 1862.

Upon the strong urging of President Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan invaded Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the Virginia peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. Although McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, Joseph E. Johnston halted his advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, then Robert E. Lee defeated him in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat. Johnston had been wounded on the battlefield and Lee replaced him as commander of the Confederate forces in Virginia. It was not until early 1865 that Lee became overall Confederate army commander. McClellan was stripped of many of his troops to reinforce John Pope's Union Army of Virginia. Pope was beaten spectacularly by Lee in the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run in August.

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North when General Lee led 55,000 men of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in American history. Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided justification for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.[2]

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside suffered near-immediate defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, when over ten thousand Union soldiers were killed or wounded. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker). Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. This was arguably Lee's greatest victoryâand the costliestâfor he lost his ablest general, Stonewall Jackson, when Jackson was mistakenly shot upon by his own troops as he scouted after the battle. Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1â3, 1863), the largest battle in North American history, which is sometimes considered the war's turning point. Lee's army suffered 28,000 casualties (versus Meade's 23,000), again forcing it to retreat to Virginia, never to launch a full-scale invasion of the North again.

Western Theater 1861â1863

While the Confederate forces had numerous successes in the Eastern Theater, they crucially failed in the West. They were driven from Missouri early in the war as result of the Battle of Pea Ridge. Leonidas Polk's invasion of Kentucky enraged the citizens who previously had declared neutrality in the war, turning that state against the Confederacy.

Nashville, Tennessee fell to the Union early in 1862. Most of the Mississippi River was opened with the taking at the Battle of Island Number Ten and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee. New Orleans, Louisiana was captured in May 1862, allowing the Union forces to begin moving up the Mississippi as well. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented unchallenged Union control of the entire river.

Braxton Bragg's second Confederate invasion of Kentucky was repulsed by Don Carlos Buell at the confused and bloody Battle of Perryville and he was narrowly defeated by William S. Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee.

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia, near the Tennessee border, where Bragg, reinforced by the corps of James Longstreet (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans despite the heroic defensive stand of George Henry Thomas, and forced him to retreat to Chattanooga, Tennessee, which Bragg then besieged.

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the west was Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and seized control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. His victory at Vicksburg cemented Union control of the Mississippi and is considered one of the turning points of the war. From there he moved on to Chattanooga, Tennessee, driving Confederate forces out and opening an invasion route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.

Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861â1865

Though geographically isolated from the battles to the east, a number of military actions took place in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, a region encompassing states and territories to the west of the Mississippi River. In 1861, Confederates launched a successful campaign into the territory of present-day Arizona and New Mexico. Residents in the southern portions of this territory adopted a secession ordinance of their own and requested that Confederate forces stationed in nearby Texas assist them in removing Union forces still stationed there. The Confederate territory of Arizona was proclaimed by Col. John Baylor after victories at Mesilla, New Mexico, and the capture of several Union forces. Confederate troops were unsuccessful in attempts to press northward in the territory and withdrew from Arizona completely in 1862 as Union reinforcements arrived from California.

- The Battle of Glorieta Pass was a small skirmish in terms of both numbers involved and losses (140 Federal, 190 Confederate). Yet the issues were large, and the battle decisive in resolving them. The Confederates might well have taken Fort Union and Denver had they not been stopped at Glorieta. As one Texan put it, "if it had not been for those devils from Pike's Peak, this country would have been ours."[3]

This small battle smashed any possibility of the Confederacy taking New Mexico and the far west territories. In April, Union volunteers from California pushed the remaining Confederates out of present-day Arizona at the Battle of Picacho Pass. In the eastern part of the United States, the fighting dragged on for three more years, but in the Southwest the war was over.[4]

The Union mounted several attempts to capture the trans-Mississippi regions of Texas and Louisiana from 1862 until the war's end. With ports to the east under blockade or capture, Texas in particular became a blockade-running haven. Texas and western Louisiana, the âback doorâ of the Confederacy, continued to provide cotton crops that were transferred overland to Matamoros, Mexico, and shipped to Europe in exchange for supplies. Determined to close this trade, the Union mounted several invasion attempts of Texas, each of them unsuccessful. Confederate victories at Galveston and the Second Battle of Sabine Pass repulsed invasion forces. The Union's disastrous Red River Campaign in western Louisiana, including a defeat at the Battle of Mansfield, effectively ended the Union's final invasion attempt of the region until the final fall of the Confederacy. Isolated from events in the east, the Civil War continued in the Trans-Mississippi Theater for several months after Robert E. Lee's surrender. The last battle of the war occurred at Battle of Palmito Ranch in southern Texasâironically a Confederate victory.

The End of the War 1864â1865

At the beginning of 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of all Union armies. He chose to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, although Meade remained the actual commander of that army. He left Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring an end to the war. Therefore, scorched earth tactics would be required in some important theaters. He devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, Meade, and Benjamin Butler would move against Lee near Richmond; Franz Sigel would invade the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman would invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell would operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel Prentiss Banks would capture Mobile, Alabama.

Union forces in the east attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's Overland Campaign") of the eastern campaign. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 66,000 casualties in six weeks), kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. He pinned down the Confederate army in the Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.

After two failed attempts (under Sigel and David Hunter) to seize key points in the Shenandoah Valley, Grant finally found a commander, Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Sheridan was sent in response to a raid by the aggressive Jubal Anderson Early, whose corps reached the outer defenses of Washington in July, before withdrawing back to the valley. Sheridan proved to be more than a match for Early, and defeated him in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural and industrial base of the valley, a strategy similar to the scorched-earth tactics Sherman would later employ in Georgia.

Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John B. Hood. The fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, was a significant factor in the re-election of Abraham Lincoln. Leaving Atlanta and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unclear destination, laying waste to much of the rest of Georgia in his celebrated "Sherman's March to the Sea," reaching the sea at Savannah, Georgia in December 1864. Burning towns and plantations as they went, Sherman's armies hauled off crops and killed livestock to retaliate and to deny use of these economic assets to the Confederacy, a consequence of Grant's scorched earth doctrine. When Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Virginia lines from the south, it was the end for Lee and his men, and for the Confederacy.

Lee attempted to escape from the besieged Petersburg and link up with Johnston in North Carolina, but he was overtaken by Grant. He surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman shortly thereafter at a local family's farmhouse in Durham, North Carolina. The Battle of Palmito Ranch, fought on May 13, 1865, in the far south of Texas, was the last land battle of the war and ended, ironically, with a Confederate victory. All Confederate land forces surrendered by June 1865. Confederate naval units surrendered as late as November 1865, with the last actions being attacks on private New England whaling ships by the CSS Shenandoah in the Bering Strait through June 28, 1865.

Analysis of the War

Why the Union prevailed (or why the Confederacy was defeated) in the Civil War has been a subject of extensive analysis and debate. Advantages widely believed to have contributed to the Union's success include:

- The more industrialized economy of the North, which aided in the production of arms and munitions.

- The Union significantly outnumbered the Confederacy, both in civilian and military population.

- Strong compatible railroad links between Union cities, which allowed for the relatively quick movement of troops. However, the first military transfer of troops, from the Shenandoah Valley to Manassas in July 1861, helped the Confederacy gain its victory at the First Battle of Bull Run. (It should be noted, however, that the Confederacy had more railroads per capita than any other country at the time.)

- The Union's larger population and greater immigration during the war, allowed for a larger pool of potential conscripts.

- The Union's possession of the U.S. merchant marine fleet and naval ships, which led to its successful blockade of Confederate ports. (The Confederacy had no navy as the war started and bought most of its ships from England and France. The South did develop several ingenious devices, including the first successful submarine, the H.L. Hunley.

- The Union's more established government, which may have resulted in less infighting and a more streamlined conduct of the war.

- The moral cause assigned to the war by the Emancipation Proclamation, which may have given the Union additional incentive to continue the war effort, and also may have encouraged international support.

- The recruitment of African Americans, including freed slaves, into the Union Army after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect. (Early in 1865, the Confederacy finally offered freedom to any slave willing to fight for the cause.)

- The Confederacy's possible squandering of resources on early audacious conventional offensives and its failure to fully use its advantages in guerrilla warfare against Union communication and transportation infrastructure.

- The Confederacy's failure to win military support from any foreign powers, mostly due to the Battle of Antietam, and the well-timed release of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Major land battles

The ten costliest land battles, measured by casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and missing) were:

| Battle (State) | Dates | Confederate Commander | Union Commander | Conf. Forces | Union Forces | Victor | Casualties |

| Battle of Gettysburg | July 1â3, 1863 | Robert E. Lee | George G. Meade | 75,000 | 82,289 | Union | 51,112 |

| (Pennsylvania) | U: 23,049 | ||||||

| C: 28,063 | |||||||

| Battle of Chickamauga | September 19â20, 1863 | Braxton Bragg | William S. Rosecrans | 66,326 | 58,222 | Conf. | 34,624 |

| (Georgia) | U: 16,170 | ||||||

| C: 18,454 | |||||||

| Battle of Chancellorsville | May 1â4, 1863 | Robert E. Lee | Joseph Hooker | 60,892 | 133,868 | Conf. | 30,099 |

| U: 17,278 | |||||||

| C: 12,821 | |||||||

| Battle of Spotsylvania Court House | May 8â19, 1864 | Robert E. Lee | Ulysses S. Grant | 50,000 | 83,000 | Unknown | 27,399 |

| (Virginia) | U: 18,399 | ||||||

| C: 9,000 | |||||||

| Battle of Antietam | September 17, 1862 | Robert E. Lee | George B. McClellan | 51,844 | 75,316 | Union | 26,134 |

| (Maryland) | U: 12,410 | ||||||

| C: 13,724 | |||||||

| Battle of the Wilderness | May 5â7, 1864 | Robert E. Lee | Ulysses S. Grant | 61,025 | 101,895 | Unknown | 25,416 |

| (Virginia) | U: 17,666 | ||||||

| C: 7,750 | |||||||

| Second Battle of Manassas | August 29â30, 1862 | Robert E. Lee | John Pope | 48,527 | 75,696 | Conf. | 25,251 |

| (Virginia) | U: 16,054 | ||||||

| C: 9,197 | |||||||

| Battle of Stones River | December 31, 1862 | Braxton Bragg | William S. Rosecrans | 37,739 | 41,400 | Union | 24,645 |

| (Tennessee) | U: 12,906 | ||||||

| C: 11,739 | |||||||

| Battle of Shiloh | April 6â7, 1862 | Albert Sidney Johnston | |||||

| (Tennessee) | P. G. T. Beauregard | Ulysses S. Grant | 40,335 | 62,682 | Union | 23,741 | |

| U: 13,047 | |||||||

| C: 10,694 | |||||||

| Battle of Fort Donelson | February 13â16, 1862 | John B. Floyd | Ulysses S. Grant | 21,000 | 27,000 | Union | 19,455 |

| (Tennessee) | Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr. | U: 2,832 | |||||

| C: 16,623 |

Other major land battles included First Bull Run, The Seven Days, Battle of Perryville, Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Vicksburg, Battle of Chattanooga, the Siege of Petersburg, and the battles of Franklin and Nashville. There was also Jackson's Valley Campaign, the Atlanta Campaign, Red River Campaign, Missouri Campaign, Valley Campaigns of 1864, and many coastal and river battles.

Major naval battles included Battle of Island Number Ten, Battle of Hampton Roads, Battle of Memphis, Battle of Drewry's Bluff, Battle of Fort Hindman, and Battle of Mobile Bay. In addition to this, a Union blockade of Confederate ports throughout the war managed to deny supplies to the Confederate states.

The most famous battle was the Battle of Hampton Roads, a duel between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia in March 1862. It was the first battle of ironclads in naval history. Technically a tie because neither ship was sunk or surrendered, the Virginia was forced back to its dock, never to fight again. The most famous foreign battle was the confrontation between the USS Kearsarge and the CSS Alabama (both wooden ships) off the coast of Cherbourg, France, in June 1864. According to naval lore, Irvine Bulloch fired off the last shot as the Alabama was sinking. He was the uncle of future U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

Civil War leaders and soldiers

One of the reasons that the American Civil War wore on as long as it did and the battles were so fierce was that most important generals on both sides had formerly served in the United States Armyâsome including Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee had served during the Mexican-American War between 1846 and 1848. Most were graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, where Lee had been commandant for 3 years in the 1850s.

Significant Southern leaders included Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, James Longstreet, P.G.T. Beauregard, John Mosby, Braxton Bragg, John Bell Hood, James Ewell Brown, William Mahone, Judah P. Benjamin, Jubal Anderson Early, and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Northern leaders included Abraham Lincoln, William H. Seward, Edwin M. Stanton, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George H. Thomas, George B. McClellan, Henry W. Halleck, Joseph Hooker, Ambrose Burnside, Irvin McDowell, Philip Sheridan, George Crook, George Armstrong Custer, Christopher "Kit" Carson, John E. Wool, George G. Meade, Winfield Hancock, Elihu Washburne, Abner Read, and Robert Gould Shaw.

Five men who served as Union officers eventually became presidents of the United States: Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley.

After the war, the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization open to Union war veterans, was founded in 1866. Confederate veterans formed the United Confederate Veterans in 1889. In 1905, a campaign medal was authorized for all Civil War veterans, known as the Civil War Campaign Medal. According to data from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the last surviving Union veteran of the conflict, Albert Woolson, died on August 2, 1956 at the age of 109, and the last Confederate veteran, John Salling, died on March 16, 1958, at the age of 112. However, William Marvel investigated the claims of both for a 1991 piece in the Civil War history magazine Blue & Gray. Using census information, he found that Salling was born in 1858, far too late to have served in the Civil War. In fact, he concluded, "Every one of the last dozen recognized Confederates was bogus." He found Woolson to be the last true veteran of the Civil War on either side; he had served as a drummer boy late in the war.

Women were not allowed to fightâthough some did fight in disguise. Clara Barton became a leader of the Union Nurses and was widely known as the "Angel of the Battlefield." She experienced the horror of 16 battles, helping behind the lines to heal the injured soldiers. Barton organized a relief program that helped to better distribute supplies to wounded soldiers of both the North and South. The founding of the American Red Cross in 1881 was due to the devotion and dedication of Clara Barton. After 1980 scholarly attention turned to ordinary soldiers, and to women and African Americans.

The question of slavery

As slavery and constitutional questions concerning states' rights were widely viewed as the major causes of the war; the victorious Union government sought to end slavery and to guarantee a perpetual union that could never be broken.

During the early part of the war, Lincoln, to hold together his war coalition of Republicans and Democrats, emphasized preservation of the Union as the sole Union objective of the war, but with the Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862 and put into effect four months later, Lincoln adopted the abolition of slavery as a second mission. The Emancipation Proclamation declared all slaves held in territory then under Confederate control to be "then, thenceforth, and forever free," but did not affect slaves in areas under Union control. It had little initial effect but served to commit the United States to the goal of ending slavery. The proclamation would be put into practical effect in Confederate territory captured over the remainder of the war.

Foreign diplomacy

Because of the Confederacy's attempt to create a new nation, recognition and support from the European powers were critical to its prospects. The Union, under United States Secretary of State William Henry Seward attempted to block the Confederacy's efforts in this sphere. The Confederates hoped that the importance of the cotton trade to Europe (the idea of cotton diplomacy) and shortages caused by the war, along with early military victories, would enable them to gather increasing European support and force a turn away from neutrality.

Lincoln's decision to announce a blockade of the Confederacy, a clear act of war, enabled Britain, followed by other European powers, to announce their neutrality in the dispute. This enabled the Confederacy to begin to attempt to gain support and funds in Europe. Jefferson Davis had picked Robert Toombs of Georgia as his first Secretary of State. Toombs, having little knowledge in foreign affairs, was replaced several months later by Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia, another choice with little suitability. Ultimately, on March 17, 1862, Jefferson selected Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana as Secretary of State, who although having more international knowledge and legal experience with international slavery disputes still failed in the end to create a dynamic foreign policy for the Confederacy.

The first attempts to achieve European recognition of the Confederacy were dispatched on February 25, 1861 and led by William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre A. Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann. The British foreign minister Lord John Russell met with them, and the French foreign minister Edouard Thouvenel received the group unofficially. However, at this point the two countries had agreed to coordinate and cooperate and would not make any rash moves.

Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept as ambassador to Britain for the Union, and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the Union's blockade. The Confederacy also attempted to initiate propaganda in Europe through journalists Henry Hotze and Edwin De Leon in Paris and London. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain. A significant challenge in Anglo-Union relations was also created by the Trent Affair, involving the Union boarding of a British mail steamer to seize James M. Mason and John Slidell, Confederate diplomats sent to Europe. However, the Union was able to smooth over the problem to some degree.

As the war continued, in late 1862, the British considered initiating an attempt to mediate the conflict. However, the unclear result of the Battle of Antietam caused them to delay this decision. Additionally, the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation further reinforced the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. As the war continued, the Confederacy's chances with Britain grew more hopeless, and they focused increasingly on France. Napoléon III proposed to offer mediation in January 1863, but this was dismissed by Seward. Despite some sympathy for the Confederacy, ultimately, France's own concerns in Mexico deterred them from substantially antagonizing the Union. As the Confederacy's situation grew more and more tenuous and their pleas increasingly ignored, in November 1864, Davis sent Duncan F. Kenner to Europe to test whether a promised emancipation could lead to possible recognition. The proposal was strictly rejected by both Britain and France.

Aftermath

The border states of Missouri and Maryland moved during the course of the war to end slavery, and in December 1864, the Congress proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, barring slavery throughout the United States; the 13th Amendment was fully ratified by the end of 1865. The 14th Amendment, defining citizenship and giving the federal government broad power to require the states to provide equal protection of the laws was adopted in 1868. The 15th Amendment guaranteeing black men (but not women) the right to vote was ratified in 1870. The 14th and 15th Amendments reversed the effects of the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of 1857, but the 14th Amendment, in particular, had unanticipated and far-reaching effects.

From the U.S. presidential election of 1876 until the election of 1964, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas gave no electoral votes to the Republican Party, with South Carolina and Louisiana making an exception only once each. Most other states that had seceded voted overwhelmingly against Republican presidential nominees also, with the same trend predominantly applying in state elections too. This phenomenon was known as the Solid South. However, starting with the election of 1964, this trend has almost completely reversed, and most of the Southern states have now become Republican strongholds.

A good deal of ill will among the Southern survivors resulted from the persistent poverty in South, the shift of political power to the North, the destruction inflicted on the South by the Union armies as the end of the war approached, and the Reconstruction program instituted in the South by the Union after the war's end. Bitterness about the war continued for decades. Some Southerners, particularly in the Deep South, maintain that the Confederacy fought for a just cause, while some Northerners continue to regard the south as backward. Southerners sometimes display Confederate flags and other Confederate symbols to show sectional pride or defiance against Northern preeminence. However, the descendants of most people on both sides have moved on.

Notes

- â House Divided Speech, Springfield, Illinois, June 16, 1858. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- â The Emancipation Proclamation Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- â Quoted in William Waldrip, "New Mexico During the Civil War," New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 28, 3, 4 (July-Oct., 1953), 256-257; cited in Richard Greenwood, "Glorieta Battlefield" (Santa Fe County, New Mexico) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1978) 8/2.

- â Determining the Facts, Reading 3: The Confederates Retrieved August 19, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Catton, Bruce. The Civil War. New York: Mariner Books/American Heritage, 1960. ISBN 0828103054.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684849445.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative (3 volumes). New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0394749138.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States). New York: Oxford University Press, [1988] 2003. ISBN 0195038630.

- McPherson, James M. What They Fought For, 1861-1865. New York: Anchor, 1995. ISBN 0385476345

- U.S. War Dept., The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880â1901.

Further reading

There have been over 50,000 books published about the Civil War. It is often cited as the single subject with the most number of books published in the United States.

Bibliographies

- Eicher, David J. The Civil War in Books: An Analytical Bibliography. University of Illinois, 1997. ISBN 0252022734

Histories and biographies

- Bedwell, Randall. War is All Hell: A Collection of Civil War Quotations. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 1999. ISBN 158182419X

- Bush, Bryan S. The Civil War Battles of the Western Theatre. Nashville, TN: Turner Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 1563114348

- Coombe, Jack D. Gunsmoke Over the Atlantic: First Naval Actions of the Civil War. New York: Bantam Books, 2002. ISBN 0553380737

- Davis, Burke. The Civil War: Strange & Fascinating Facts. New York: Wings Books (Random House), 1960. ISBN 0517371510

- Duncan, Russel, ed. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Leters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992. ISBN 0820321745

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0804736413

- Eisenschiml, Otto, and Ralph Newman. The Civil War: An American Iliad. New York: Smithmark, 1947. ISBN 0831713372

- Fisher, Garry. Rebel Cornbread and Yankee Coffee: Authentic Civil War Cooking and Camaraderie. Birmingham, AL: Crane Hill, 2001. ISBN 1575871750

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography (4 volumes). New York: Scribnerâs, 1940.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command (3 volumes). New York: Scribnerâs, 1946. ISBN 0684859793

- Garrison, Webb. True Tales of the Civil War. New York: Gramercy Books (Random House), 1988. ISBN 0517162660

- Garrison, Webb. Civil War Schemes and Plots. New York: Gramercy Books, 1997. ISBN 0517162873

- McPherson, James M. What They Fought For, 1861-1865. New York: Anchor, 1995. ISBN 0385476345

- Ragan, Mark K. Submarine Warfare in the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1999. ISBN 0306811979

- Van Doren Stern, Philip. Secret Missions of the Civil War. New York: Random House Publishing, 1959. ISBN 0517000024

- Varhola, Michael J. Everyday Life During the Civil War. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books, 1999. ISBN 0898799228

- Woodword, C. Vann, ed. Mary Chesnut's Civil War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981. ISBN 0300029799

Novels about the war

- Crane, Stephen, The Red Badge of Courage

- Doctorow, E.L., The March

- Frazier, Charles, Cold Mountain

- Mitchell, Margaret, Gone with the Wind

- Reed, Ishmael, Flight to Canada

- Shaara, Jeffrey, Gods and Generals

- Shaara, Jeffrey, The Last Full Measure

- Shaara, Michael, The Killer Angels

- Street, James, By Valour and Arms

- Verne, Jules, North against South (Nord Contre Sud)

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Civil War photos at the National Archives

- Bruce T. Gourley, 2002, "Recent Historiography on Religion and the American Civil War" Religion and the American Civil War

- United States Civil War

- The Civil War, a PBS documentary by Ken Burns

- Individual states' contributions to the Civil War: Florida, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania

- Civil War TrailsâA project to map out sites related to the Civil War in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina

- Civil War Audio Resources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.