Volga River

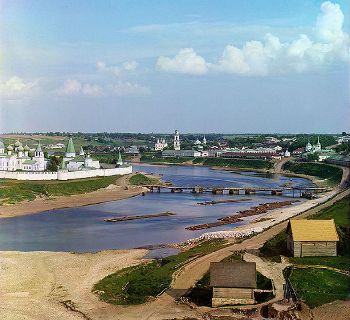

| The Volga at Yaroslavl | |

| Origin | Valdai Hills, Tver Oblast |

| Mouth | Caspian Sea |

| Basin countries | Russian Federation |

| Length | 3,531 km (2,194 mi) |

| Source elevation | 228 m (748 ft)[1] |

| Mouth elevation | −28 m (−92 ft)[1] |

The Volga (Russian: Во́лга) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga is widely regarded as the national river of Russia.

Important since ancient times as a trade route, the river flows for 3,531 km (2,194 mi) through forests, forest steppes, and steppes from the Valdai Hills in Central Russia to the Caspian Sea. Four of the ten largest cities of Russia, including the nation's capital, Moscow, are located in the Volga's drainage basin. Some of the largest reservoirs in the world are located along the Volga River.

The river has a symbolic meaning in Russian culture – Russian literature and folklore often refer to it as "Mother Volga," reflecting the river's importance to the Russian people.

Etymology

The name Volga originates from Lithuanian language which signifies the long river: "ilga" in Lithuanian means "long" (up until the annexation of Novgorod at 1481 C.E. the upper Volga was a part of Lithuanian ethnic state). Despite the fact that Lithuanian word "vilga" means "soaking." Several upper Volga tributaries are also of Lithuanian origin like Uzola ("ąžuolas" means "oak") and Oka ("auka" means "offering").

The Russian hydronym Volga (Волга) derives from Proto-Slavic vòlga meaning "wetness, moisture," which is preserved in many Slavic languages.[2]

The Scythian name for the Volga was Rahā, literally meaning "wetness." The Scythian name survives in modern Moksha Rav (Рав).[3]

Description

The Volga is the longest river in Europe. It flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of 3,531 km (2,194 mi), and a catchment area of 1,360,000 km² (530,000 sq mi). It is also Europe's largest river in terms of average discharge at delta – between 8,000 m3/s (280,000 cu ft/s) and 8,500 m3/s (300,000 cu ft/s) – and of drainage basin.[4] The Volga freezes for most of its length for three months each year.[1]

It belongs to the closed basin of the Caspian Sea, being the longest river to flow into a closed basin. Rising in the Valdai Hills 225 meters (740 ft) above sea level northwest of Moscow and about 320 kilometers (200 mi) southeast of Saint Petersburg, the Volga heads east past Lake Sterzh, Tver, Dubna, Rybinsk, Yaroslavl, Nizhny Novgorod, and Kazan. From there it turns south, flows past Ulyanovsk, Tolyatti, Samara, Saratov, and Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad), and discharges into the Caspian Sea below Astrakhan at 28 meters (92 ft) below sea level.[1] At its most strategic point, it bends toward the Don ("the big bend").

The Volga has many tributaries, most importantly the rivers Kama, the Oka, the Vetluga, and the Sura. The Volga and its tributaries form the Volga river system, which flows through an area of about 1,350,000 square kilometers (521,238 sq mi) in the most heavily populated part of Russia.[1] The Volga Delta includes as many as 500 channels and smaller rivers. Lotus flowers can be found along the river. For example, a rare species, the Caspian lotus, grows in the Astrakhan Nature Reserve in the Volga River delta, and there is a Lotus lake in the floodplain of the Volga and Akhtuba rivers near the small village of Krasny Buksir.[5]

The Volga drains most of Western Russia. Its many large reservoirs provide irrigation and hydroelectric power. The Moscow Canal, the Volga–Don Canal, and the Volga–Baltic Waterway form navigable waterways connecting Moscow to the White Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. High levels of chemical pollution have adversely affected the river and its habitats.

The fertile river valley provides large quantities of wheat, and also has many mineral riches. A substantial petroleum industry centers on the Volga valley. Other resources include natural gas, salt, and potash.

Delta

The Volga Delta, where the Volga drains into the Caspian Sea, is the largest river delta in Europe. The delta is located in the Caspian Depression—the far eastern part of the delta lies in Kazakhstan. The delta drains into the Caspian approximately 60 kilometers (37 mi) downstream from the city of Astrakhan.

The Volga Delta grew significantly in the twentieth century because of changes in the level of the Caspian Sea. In 1880, the delta had an area of 3,222 square kilometers (1,244 sq mi). Today the Volga Delta covers an area of 27,224 square kilometers (10,511 sq mi) and is approximately 160 kilometers (100 mi) across. The delta lies in the arid climate zone, characterized by very little rainfall, receiving less than one inch of rainfall in January and in July in normal years. Strong winds often sweep across the delta and form linear dunes. Along the front of the delta, there are muddy sand shoals, mudflats, and coquina banks.

The changing level of the Caspian Sea has resulted in three distinct zones in the delta.

The higher areas of the first zone are known as "Baer's mounds," named after researcher Karl Ernst von Baer who worked in this region. These mounds are linear ridges of clayey sands, averaging about 8 meters (26 ft) in height, ranging from 5 to 22 meters (16 to 72 ft). They are between 0.4 to 10 kilometers (0.25 to 6.2 mi) in length.[6] Between the Baer's mounds are depressions that fill with water and become either fresh or saline bays. These depressions, called "ilmens" (from Russian through Finnish, "small lake," as in Russia's Lake Ilmen), used to form part of the early, very deep river delta but gradually became separated from it. Because of their isolation from the fresh waters of the Volga, they are becoming increasingly saline. Together they form a vast and extremely diverse area of western substeppe, which, because of the varying degrees of wetness and salinization, house a wealth of flora and fauna.[7] The origin of these mounds is still debated: The early suggestion that they were formed by aeolian (wind) action is now discredited, and now they are thought to have arisen either underwater or through river flow.[6]

The second zone, in the delta proper, generally has very little relief (usually less than one meter), and is the site of active and abandoned water channels, small dunes, and algal flats.

The third zone is composed of a broad platform extending up to 60 kilometers (37 mi) offshore, and is the submarine part of the delta.

- Wildlife

The delta has been protected since the early 1900s, with one of the first Russian nature preserves (Astrakhan Nature Reserve) having been set up there in 1919. Much of its local fauna is considered endangered. The delta is a major staging area for many species of water birds, raptors and passerines. Although the delta is best known for its sturgeons, catfish and carp are also found in large numbers in the delta region. It is the only place in Russia where pelicans and flamingos may be found.[8]

- Pollution

Industrial and agricultural modification to the delta plain has resulted in significant wetland loss. Between 1984 and 2001, the delta lost 277 square kilometers (107 sq mi) of wetlands, or an average of approximately 16 square kilometers (6.2 sq mi) per year, from natural and human-induced causes. The Volga discharges large amounts of industrial waste and sediment into the relatively shallow northern part of the Caspian Sea. The added fertilizers nourish the algal blooms that grow on the surface of the sea, allowing them to grow larger.

Confluences

Downstream to Upstream

- Akhtuba (near Volzhsky), a distributary

- Bolshoy Irgiz (near Volsk)

- Samara (in Samara)

- Kama (south of Kazan)

- Kazanka (in Kazan)

- Sviyaga (west of Kazan)

- Vetluga (near Kozmodemyansk)

- Sura (in Vasilsursk)

- Kerzhenets (near Lyskovo)

- Oka (in Nizhny Novgorod)

- Uzola (near Balakhna)

- Unzha (near Yuryevets)

- Kostroma (in Kostroma)

- Kotorosl (in Yaroslavl)

- Sheksna (in Cherepovets)

- Mologa (near Vesyegonsk)

- Kashinka (near Kalyazin)

- Nerl (near Kalyazin)

- Medveditsa (near Kimry)

- Dubna (in Dubna)

- Shosha (near Konakovo)

- Tvertsa (in Tver)

- Vazuza (in Zubtsov)

- Selizharovka (in Selizharovo)

Reservoirs

A number of large hydroelectric reservoirs were constructed on the Volga during the Soviet era. They are:

- Volgograd Reservoir

- Saratov Reservoir

- Kuybyshev Reservoir – the largest in Europe by surface

- Cheboksary Reservoir

- Gorky Reservoir

- Rybinsk Reservoir

- Uglich Reservoir

- Ivankovo Reservoir

Cities

- Kazan

- Nizhny Novgorod

- Samara

- Volgograd

- Saratov

- Tolyatti

- Yaroslavl

- Astrakhan

- Ulyanovsk

- Cheboksary

- Tver

Human history

Historically, the river served as an important meeting place of various Eurasian civilizations.[9][10]

Many different ethnicities have lived on the Volga river, with the Volga–Oka region occupied for at least 9,000 years. The area has supported a bone and antler industry for producing bone arrowheads, spearheads, lanceheads, daggers, hunter's knives, and awls. The craftsmen also used local quartz and imported flint.[11] Among the first recorded people along the upper Volga were also the Finnic Mari (Мари) and Merya (Мäрӹ) people.

Where the Volga flows through the steppes the area was inhabited by the Sarmatians from 200 B.C.E.[12][10]

Since ancient times, the Volga river was an important trade route where not only Slavic, Turkic, and Finnic peoples lived, but also the Arab world of the Middle East met the Varangian people of the Nordic countries through trading.[13]

Furthermore, the river played a vital role in the commerce of the Byzantine people. The ancient scholar Varangian of Alexandria mentions the lower Volga, calling it the Rha, which was the Scythian name for the river.[14]

During Classical antiquity, the Volga formed the boundary between the territories of the Cimmerians in the Caucasian Steppe and the Scythians in the Caspian Steppe. After the Scythians migrated to the west and displaced the Cimmerians, the Volga became the boundary between the territories of the Scythians in the Pontic and Caspian Steppes and the Massagetae in the Caspian and Transcaspian steppes.[15]

Between the second and fifth centuries Baltic people were very widespread in today's European Russia, from the Sozh River to today's Moscow. They covered much of today's Central Russia and intermingled with the East Slavs.[16]

By 370 C.E., the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430, they had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe. The were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time.[17] Their arrival is associated with the migration westward of the Alans, an Iranian people.[18]

Apart from the Huns, the earliest Turkic tribes arrived in the seventh century and assimilated some Finno-Ugric and Indo-European population on the middle and lower Volga. Another Turkic group, the Nogais, formerly inhabited the lower Volga steppes.

In the eighth and ninth centuries colonization also began from Kievan Rus'. Slavs from Kievan Rus' brought Christianity to the upper Volga, and a portion of non-Slavic local people adopted Christianity and gradually became the East Slavs. The remainder of the Mari people migrated to the east far inland. In the course of several centuries the Slavs assimilated the indigenous Finnic populations, such as the Merya and Meshchera peoples. Also Khazar and Bulgar peoples inhabited the upper, middle, and lower regions of the Volga River basin.

Subsequently, the river basin played an important role in the movements of peoples from Asia to Europe. A powerful polity of Volga Bulgaria once flourished where the Kama joins the Volga, while Khazaria controlled the lower stretches of the river. The Turkic Christian Chuvash and Muslim Volga Tatars are descendants of the population of medieval Volga Bulgaria. Such Volga cities as Atil, Saqsin, or Sarai were among the largest in the medieval world. The river served as an important trade route connecting Scandinavia, Finnic areas with the various Slavic tribes and Turkic, Germanic, Finnic and other people in Old Rus', and Volga Bulgaria with Khazaria, Persia, and the Arab world.

Khazars were replaced by Kipchaks, Kimeks and Mongols, who founded the Golden Horde in the lower reaches of the Volga. Later their empire divided into the Khanate of Kazan and Khanate of Astrakhan, both of which were conquered by the Russians in the course of the sixteenth century Russo-Kazan Wars.

The Russian ethnicity in Western Russia and around the Volga river evolved to a very large extent, next to other tribes, out of the East Slavic tribe of the Buzhans and Vyatichis. The Vyatichis were originally concentrated on the Oka river.[19]

Twentieth-century

During the Russian Civil War, both sides fielded warships on the Volga. In 1918, the Red Volga Flotilla participated in driving the Whites eastward, from the Middle Volga at Kazan to the Kama and eventually to Ufa on the Belaya.[20]

During World War II, the city on the big bend of the Volga, currently known as Volgograd (formerly Tsaritsyn (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (1925–1961)), witnessed the Battle of Stalingrad, in which the Soviet Union and the German forces were deadlocked in a stalemate battle for access to the river. The Volga was (and still is) a vital transport route between central Russia and the Caspian Sea, providing access to the oil fields of the Absheron Peninsula. Hitler planned to use access to the oil fields of Azerbaijan to fuel future German conquests. Whoever held both sides of the river could move forces across the river to defeat the enemy's fortifications beyond the river. By taking the river, Hitler's Germany would have been able to move supplies, guns, and men into the northern part of Russia. At the same time, Germany could permanently deny this transport route by the Soviet Union, hampering its access to oil and to supplies via the Persian Corridor. For this reason, many amphibious military assaults were brought about in an attempt to remove the other side from the banks of the river.

Under the Soviet Union a slice of the Volga region home to a German minority group, the Volga Germans, was turned into the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Catherine the Great had issued a manifesto in 1763 inviting all foreigners to come and populate the region, offering them numerous incentives to do so.[21] Because of conditions in German territories, Germans responded in the largest numbers.

Construction of Soviet Union-era dams often involved enforced resettlement of huge numbers of people, as well as destruction of their historical heritage. For instance, the town of Mologa was flooded for the purpose of constructing the Rybinsk Reservoir (then the largest artificial lake in the world). The construction of the Uglich Reservoir caused the flooding of several monasteries with buildings dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In such cases the ecological and cultural damage often outbalanced any economic advantage:

In all, Soviet dams flooded 2,600 villages and 165 cities, almost 78,000 sq. km. – the area of Maryland, Delaware, Massachusetts, and New Jersey combined – including nearly 31,000 sq. km. of agricultural land and 31,000 sq. km. of forestland.[22]

The Volga, widened for navigation purposes with construction of huge dams during the years of Joseph Stalin's industrialization, is of great importance to inland shipping and transport in Russia. All the dams in the river have been equipped with large (double) ship locks, so that vessels of considerable dimensions can travel from the Caspian Sea almost to the upstream end of the river.

Connections with the river Don and the Black Sea are possible through the Volga–Don Canal. Connections with the lakes of the North (Lake Ladoga, Lake Onega), Saint Petersburg and the Baltic Sea are possible through the Volga–Baltic Waterway; and commerce with Moscow is through the Moscow Canal connecting the Volga and the Moskva River.

This infrastructure was designed for vessels of a relatively large scale (lock dimensions of 290 meters (950 ft) x 30 meters (98 ft) on the Volga, slightly smaller on some of the other rivers and canals) and spans many thousands of kilometers. A number of formerly state-run, now mostly privatized, companies operate passenger and cargo vessels on the river.

In the later Soviet era, up to modern times, grain and oil have been among the largest cargo exports using the Volga. Until recently access to the Russian waterways was granted to foreign vessels on a very limited scale. Increasing contact between the European Union and Russia led to new policies with regard to the access to the Russian inland waterways.

Significance to Russia

In 1839 Robert Bremner referred to the Volga as an essential part of Russia, a cornerstone of the life of Russian people. He said, "Without this river the Russians could not live."[23] At the time of Bremner’s survey, half of the Russian empire’s fish was caught in the single stretch of river by Astrakhan, a city in the upper part of the Volga Delta, 60 miles (100 km) from the Caspian Sea.[24]

The river has done far more than feed the Russian people, it has been crucial to Russia’s commercial, cultural, and imperial development. Numerous tribes arrived, some taking up residence on its banks, others using the river to transport their goods to trade in distant lands. The multi-ethnic populations that continue to live in the region reflect the importance of the river in times past, an importance that is not lost today. As a Vesti news report from 2019 noted, "Without the Volga, there would be no Russia."[24]

The meaning of the river to the Russian people is reflected in their name for her, Волга-матушка Volga-Matushka ("Mother Volga"). The construction of 11 hydroelectric power stations in 1930-1940 was a symbol of Russia`s industrialization, and Soviet sculptors erected huge sculptures near them upon their completion. Naturally, they created monuments to Lenin or Stalin were erected. However, a special monument, the Mother Volga monument, symbolizing the Volga River was erected near the Rybinsk power station, on an island formed after the rise of the water level in the river, with the monument rising beautifully above the water surface.

Satellite imagery

In popular culture

The Volga river is very special to the Russian people. In Russian Russian literature and folklore it is often referred to as Волга-матушка Volga-Matushka (Mother Volga).

Literature

- Without a Dowry, The Storm – dramas by the Russian playwright Aleksandr Ostrovsky

- In the Forests, On the Hills – novels by Pavel Melnikov

- Yegor Bulychov and Others, Dostigayev and Others – plays by Maxim Gorky

- "Distance After Distance" – poem by Aleksandr Tvardovsky

- "On the Volga" – a poem by Nikolay Nekrasov

- "Volga and Vazuza" – a poem by Samuil Marshak

- The Precipice – a novel by Ivan Goncharov

- Volga Se Ganga - a novel by Hindi language writer Rahul Sankrityayan

Cinema

- Volga-Volga (1938) – a Soviet film comedy directed by Grigori Aleksandrov

- Ekaterina Voronina (1957) – Soviet drama film directed by Isidor Annensky

- The Bridge Is Built (1965) – a Soviet film about the construction of a road bridge across the Volga in Saratov by Oleg Efremov and Gavriil Egiazarov

- A Cruel Romance (1984) – romantic drama directed by Eldar Ryazanov

- Election Day (2007) – Russian comedy film directed by Oleg Fomin

Music

- The Song of the Volga Boatmen

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Richard L. Scheffel and Susan J. Werner (eds.), Natural Wonders of the World (The Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 1988, ISBN 978-0895770875).

- ↑ Max Vasmer, The Etymological Dictionary of Russian Language - in 4 Volumes (AST, 2009, ISBN 978-5170599325).

- ↑ Janet M. Hartley, The Volga: A History of Russia's Greatest River (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022, ISBN 978-0300266412).

- ↑ Harald J. L. Leummens, Volga River Basin (Russia) Springer, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ↑ Alexandra Guzeva, Where to see the blooming lotus in Russia Russia Beyond, July 11, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Eric Bird, Encyclopedia of the World's Coastal Landforms (Springer, 2010, ISBN 978-1402086380).

- ↑ Valentin Golub and N. Tchorbadze, Vegetation communities of western substeppe ilmens of the Volga delta, Phytocoenologia 25(4) (1995): 449-466.

- ↑ Animals in the Volga river Volga River. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ↑ Edward N. Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Belknap Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0674062078).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Tim McNeese, The Volga River (Facts on File, 2005, ISBN 978-0791082478).

- ↑ M. Zhilin, Early Mesolithic bone arrowheads from the Volga-Oka interfluve, central Russia Fennoscandia archaeologica XXXII (2015): 35-54. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Amazon" Burial Discovered in Russia Archaeology Magazine, August 14, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ↑ Rym Ghazal, When the Arabs met the Vikings: New discovery suggests ancient links The National, May 6, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ↑ Claudius Ptolemy, Geography of Claudius Ptolemy (Cosimo Classics, 2011, ISBN 978-1605204383).

- ↑ Jadwiga Pstrusinska and Andrew Fear (eds.), Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia (Archeobooks, 2000, ISBN 978-8371883378).

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas, The Balts (Frederick A. Praeger, 1963, ISBN 978-0500020302).

- ↑ Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila (Cambridge University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1107633889).

- ↑ Denis Sinor, (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia (Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0521243049).

- ↑ Mikhail Zhirohov and David Nicolle, The Khazars: A Judeo-Turkish Empire on the Steppes, 7th–11th Centuries AD (Osprey Publishing, 2019, ISBN 978-1472830135).

- ↑ Fyodor Raskolnikov, Brian Pearce (trans.), Introduction Tales of Sub-lieutenant Ilyin. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ↑ Steven H. Schreiber, Catherine's Manifesto 1763 NORKA, April 2, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ↑ Paul R. Josephson, Industrialized Nature: Brute Force Technology and the Transformation of the Natural World (Island Press, 2002, ISBN 978-1559637770), 31.

- ↑ Robert Bremner, Excursions in the Interior of Russia (HardPress Publishing, 2013 (original 1839), ISBN 978-1313006972).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Matthew Janney, ‘Mother Volga’ has always been Russia’s lifeblood The Spectator, January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bird, Eric. Encyclopedia of the World's Coastal Landforms. Springer, 2010. ISBN 978-1402086380

- Gimbutas, Marija. The Balts. Frederick A. Praeger, 1963. ISBN 978-0500020302

- Hartley, Janet M. The Volga: A History of Russia's Greatest River. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022. ISBN 978-0300266412

- Josephson, Paul R. Industrialized Nature: Brute Force Technology and the Transformation of the Natural World. Island Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1559637770

- Luttwak, Edward N. The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Belknap Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0674062078

- Maas Michael, (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1107633889

- McNeese, Tim. The Volga River. Facts on File, 2005. ISBN 978-0791082478

- Pstrusinska, Jadwiga, and Andrew Fear (eds.). Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Archeobooks, 2000. ISBN 978-8371883378

- Ptolemy, Claudius. Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Cosimo Classics, 2011. ISBN 978-1605204383

- Scheffel, Richard L., and Susan J. Werner (eds.). Natural Wonders of the World. The Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 1988. ISBN 978-0895770875

- Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0521243049

- Vasmer, Max. The Etymological Dictionary of Russian Language - in 4 Volumes. AST, 2009. ISBN 978-5170599325

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Volga Delta and the Caspian Sea Earth from Space

- Volga River, Russia Travel All Russia

- The Great Volga River Route (GVRR) Project UNESCO World Heritage Convention

- Earth from Space: Volga Delta European Space Agency

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.