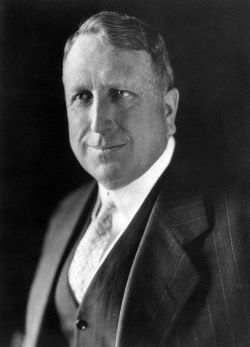

William Randolph Hearst

| William Randolph Hearst |

|---|

| Born |

| April 29, 1863 San Francisco, California, USA |

| Died |

| August 14, 1951 Los Angeles, California, USA |

William Randolph Hearst (April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper magnate, born in San Francisco, California. Hearst acquired and developed a series of influential newspapers, starting with the San Francisco Examiner in 1887, forging them into a national brand. These papers became known for sensationalist writing and agitation in favor of the Spanish-American War. The term yellow journalism (a pejorative reference to scandal-mongering, sensationalism, jingoism, and similar practices) was derived from the New York Journal's color comic strip, The Yellow Kid.

Hearst served two terms in the United States Congress, and had great political ambition, often using his newspapers to promote his views. Near the end of his life he turned to philanthropy, establishing what came to be called the Hearst Foundation, which provides grants for programs in the areas of education, social services, health, and cultural activities.

Life

William Randolph Hearst was born on April 29, 1863, in San Francisco, California. He was the only son of George Hearst, a millionaire miner, rancher, and U.S. senator (1886-1891) and Phoebe Apperson Hearst. He enrolled in Harvard College, where he studied for two years, never graduating.

In 1903, Hearst married Millicent Veronica Willson (1882–1974), a chorus girl, in New York City. Nearly 20 years her senior, Hearst had been seeing her since she was 16. The couple had five sons: George Randolph Hearst (1904–1972), William Randolph Hearst Jr. (1908–1993), John Randolph Hearst (1910–1958), and twins Randolph Apperson Hearst (1915–2000) and David Whitmire Hearst (1915–1986).

Hearst became involved in an affair with popular film actress and comedienne Marion Davies (1897–1961), and from about 1919 he lived openly with her in California. Millicent separated from her husband in the mid-1920s after tiring of his longtime affair with Davies, but the couple remained legally married until Hearst's death. Millicent built an independent life for herself in New York City as a leading philanthropist, was active in society, and created the Free Milk Fund for the poor in 1921.

Hearst died in Beverly Hills, Calif., on Aug. 14, 1951, at age 88. He is buried at the Cypress Lawn Cemetery in Colma, California.[1]

Publishing business

Searching for an occupation, in 1887 Hearst took over the management of a newspaper which his father had accepted as payment of a gambling debt, the San Francisco Examiner. Giving his paper a grand motto, "Monarch of the Dailies," he acquired the best equipment and the most talented writers of the time. A self-proclaimed populist, Hearst went on to publish stories of municipal and financial corruption, often attacking companies in which his own family held an interest. Within a few years, his paper dominated the San Francisco market.

New York Morning Journal

In 1895, with the financial support of his mother, Hearst bought the failing New York Morning Journal, hiring writers like Stephen Crane and Julian Hawthorne, and entering into a head-to-head circulation war with his former mentor, Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World, from whom he "stole" Richard Felton Outcault, the inventor of color comic strip. Hearst's was the only major newspaper in the East to support William Jennings Bryan and Bimetallism in 1896. The New York Journal (later New York Journal-American) attained unprecedented levels of circulation through reducing its price and publishing sensational articles on subjects like crime and pseudoscience.

Support for Spanish-American War

Hearst used his paper to fight tenaciously to liberate Cuba from Spanish rule. He publicized the situation, trying to sell more copies than his rival Pulitzer. Both Hearst and Pulitzer published images of Spanish troops placing Cubans into concentration camps where they suffered and died from disease and hunger. The term yellow journalism, which was derived from the name of The Yellow Kid comic strip in the Journal, was used to refer to the sensational style of newspaper articles that resulted from this competition.

Expansion

In part to aid in his political ambitions, Hearst opened newspapers in some other cities, among them Chicago, Los Angeles, and Boston. The creation of his Chicago paper was requested by the Democratic National Committee and Hearst used this as an excuse for his mother to transfer him the necessary start-up funds. By the mid-1920s he had a nation-wide string of 28 newspapers, among them the Los Angeles Examiner, the Boston American, the Atlanta Georgian, the Chicago Examiner, the Detroit Times, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Washington Times, and Washington Herald, and his flagship the San Francisco Examiner.

Hearst also diversified his publishing interests into book publishing and magazines; several of the latter are still extant, including such well-known periodicals as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Town and Country, and Harper's Bazaar.

In 1924, he opened the New York Daily Mirror, a tabloid frankly imitating the New York Daily News. Among his other holdings were two news services, Universal News and International News Service; King Features Syndicate; a film company, Cosmopolitan Productions; extensive New York City real estate; and thousands of acres of land in California and Mexico, along with timber and mining interests.

As a newspaper publisher, Hearst promoted writers and cartoonists despite the lack of any apparent demand for them by his readers. The press critic A.J. Liebling (1981) noted that many Hearst stars would not be deemed employable elsewhere. One Hearst favorite, George Herriman, was the inventor of the dizzy comic strip Krazy Kat. Not especially popular with either readers or editors at the time, it is now considered by many to be a classic, a belief once held only by Hearst himself.

The Hearst news empire reached a circulation and revenue peak about 1928, but the economic collapse of the Great Depression and the vast over-extension of his empire cost him control of his holdings. It is unlikely that the newspapers ever paid their own way; mining, ranching, and forestry provided whatever dividends the Hearst Corporation paid out. When the collapse came, all Hearst properties were hit hard, but none more so than the papers; adding to the burden were the Chief's now-reactionary politics, increasingly at odds with those of his readers.

Refused the right to sell another round of bonds to unsuspecting investors, the shaky empire tottered. Unable to service its existing debts, Hearst Corporation faced a court-mandated reorganization in 1936. From this point, Hearst was just another employee, subject to the directives of an outside manager. Newspapers and other properties were liquidated, the film company shut down; there was even a well-publicized sale of art and antiquities. While World War II restored circulation and advertising revenues, his great days were over.

Hearst died in 1951, aged 88, at Beverly Hills, California, and is buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California.

Political career: from liberal to conservative

Although he served two terms in the U.S. Congress, Hearst's political ambitions were mostly frustrated. A Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives (1903–1907), he narrowly failed in attempts to become mayor of New York City (1905 and 1909) and governor of New York (1906). He was defeated for the governorship by Charles Evans Hughes.

His defeat in the New York City mayoral election where he ran under a third party of his own creation (The Municipal Ownership League) is widely attributed to Tammany Hall, the dominant (and corrupt) Democratic organization in New York City at the time.

An opponent of the British Empire, Hearst opposed American involvement in the First World War and attacked the formation of the League of Nations.

Hearst's reputation suffered in the 1930s as his political views changed. In 1932, he was a major supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt. His newspapers energetically supported the New Deal throughout 1933 and 1934. Hearst broke with FDR in the spring of 1935 when the President vetoed the Patman Bonus Bill. Hearst papers carried the old publisher's rambling, vitriolic, all-capital-letters editorials, but he no longer employed the energetic reporters, editorialists, and columnists who might have made a serious attack. His newspaper audience was the same working class that Roosevelt swept by three-to-one margins in the 1936 election.

In 1934, after checking with Jewish leaders to make sure the visit would prove of benefit to Jews, Hearst went to Berlin to interview Adolf Hitler. Hitler asked why he was so misunderstood by the American press. Because Americans believe in democracy, Hearst answered bluntly, "and are averse to dictatorship."[2]

Criticisms

As Martin Lee and Norman Solomon noted in their 1990 book Unreliable Sources, Hearst "routinely invented sensational stories, faked interviews, ran phony pictures and distorted real events."[3] However, this criticism can also be leveled at many other newspapers of the time; ideas of objectivity had not taken hold in American journalism, and readers expected fiction in their stories.[4]

Hearst's use of "yellow journalism" techniques in his New York Journal to whip up popular support for U.S. military actions in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines was criticized in Upton Sinclair's 1920 book, The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism. According to Sinclair, Hearst's newspaper employees were "willing by deliberate and shameful lies, made out of whole cloth, to stir nations to enmity and drive them to murderous war." Sinclair also asserted that in the early twentieth century Hearst's newspapers lied "remorselessly about radicals," excluded "the word Socialist from their columns" and obeyed "a standing order in all Hearst offices that American Socialism shall never be mentioned favorably." In addition, Sinclair charged that Hearst's "Universal News Bureau" re-wrote the news of the London morning papers in the Hearst office in New York and then fraudulently sent it out to American afternoon newspapers under the by-lines of imaginary names of non-existent "Hearst correspondents" in London, Paris, Venice, Rome, Berlin, and so forth.

Just as Hearst produced sensational news regarding others, so he himself was the target of rumor and speculation. In 1924, silent film producer Thomas Harper Ince ("The Father of the Western") died suddenly while on a weekend cruise in honor of Ince's forty-second birthday aboard Hearst's lavish yacht The Oneida. Other prominent guests in attendance were actor Charlie Chaplin, newspaper columnist Louella Parsons, author Elinor Glyn, and Hearst's long-time mistress, Marion Davies. For years, rumors circulated that Hearst had shot Ince in a fit of jealousy (or shot Ince accidentally while fighting with Chaplin over Davies) and used his power and influence to cover up the truth. Patty Hearst's 1994 novel, Murder at San Simeon, and a fictional 2001 film, The Cat's Meow, were based on these rumors.

Citizen Kane

Orson Welles' 1941 film Citizen Kane was a retelling of Hearst's life. Welles and co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz added elements from the lives of other rich men of the time, among them Samuel Insull and Howard Hughes into Kane. Hearst used all his resources and influence in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent its release, including offering significant money to destroy all prints of the film and burn the negative. Welles and his studio resisted the pressure, but Hearst and his Hollywood friends succeeded in getting the theater chains of the time to limit bookings of Kane, resulting in poor box-office numbers and harming Welles' profits.

Fifty years after Hearst's death, Citizen Kane's reputation seems secure—it was ranked #1 on the list of the American Film Institute's[5] 100 greatest films of all time—while Hearst's own image has largely been shaped by the film. The film painted a dark portrait of Hearst, and was devastating to the reputation of Marion Davies, fictionalizing her as a talentless drunk. Many years later, Orson Welles said his only regret about Kane was the damage it had done to Davies.

Patty Hearst

In 1974, Hearst's granddaughter, Patty Hearst, the third of five daughters of his son Randolph Apperson Hearst, made front pages nationwide when she was kidnapped by an extremist group, the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), and was soon after caught on film helping the group to rob banks. She renounced the SLA soon after her arrest. Her defense was largely based around the claim that her actions could be attributed to being brainwashed. It was also seen as a severe case of the "Stockholm syndrome," in which captives become sympathetic with their captors.

Her seven-year prison term was eventually commuted by President Jimmy Carter, and Hearst was released from prison on February 1, 1979, having served only 22 months. She was granted a full pardon by President Bill Clinton on January 20, 2001, the final day of his presidency.

Legacy

William Randolph Hearst left behind a huge legacy. While his name may be infamous to many, his legacy remains that of an astoundingly good businessman, politician, and philanthropist.

The Hearst Corporation continues as a large, privately held media conglomerate based in New York City. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Hearst Corporation owned 12 newspapers, 25 magazines (including the popular Cosmopolitan), in addition to managing other media enterprises.

Hearst constructed a spectacular castle on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean, on a 240,000 acre (970 km²) ranch at San Simeon, California. He furnished it with antiques, art, and entire rooms brought from the great houses of Europe. Hearst formally named the estate "La Cuesta Encantada" ("The Enchanted Hill"), but he usually just called it "the ranch."[6] It was donated by the Hearst Corporation to the state of California in 1957, and is now a State Historical Monument and a National Historic Landmark, open for public tours.

Hearst also bought St Donat's Castle near Llantwit Major in South Wales. As with San Simeon, he spent a fortune renovating the castle, bringing electricity not only to his residence but to the surrounding area. The locals enjoyed having Hearst in residence at the castle; he paid his employees very well, and his arrivals always created a big stir in a community not used to American excesses. Hearst spent much of his time entertaining influential people at his estates. Although he sold it again, Hearst's extensive renovations continue to be appreciated. George Bernard Shaw, upon visiting St. Donat's, was quoted as saying: "This is what God would have built if he had had the money."

Hearst also founded the California Charities Foundation, which was renamed the Hearst Foundation after his death. The foundation has headquarters in New York City and San Francisco, and focuses on education, health, social service, and culture.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Hearst 1863-1951, ZPub. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

- ↑ Peter Conradi, 2004, Hitler's Piano Player: The Rise and Fall of Ernst Hanfstaengl: Confidant of Hitler, Ally of FDR, Carroll & Graf. 174. ISBN 078671283X

- ↑ Martin Lee, and Martin Solomon, 1991, Unreliable Sources: A Guide to Detecting Bias in News Media, L Trade Paper. ISBN 0818405619

- ↑ David Nasaw, 2001, The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst, Mariner Books. ISBN 0618154469

- ↑ AFI's 100 YEARS...100 MOVIES, American Film Institute. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Welcome to Hearst Castle, Hearst Castle.

- ↑ The William Randolph Hearst Foundations, Hearst Foundation. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell, W. Joseph. 2003. Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies. Praeger Paperback. ISBN 0275981134

- Campbell, W. Joseph. 2006. The Year That Defined American Journalism. Routledge. ISBN 0415977037

- Hearst, William Randolph, Jr. 2001. The Hearsts: Father and Son. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 1570984026

- Liebling, A.J. 1981. The Press. Pantheon. ISBN 0394748492

- Lundberg, Ferdinand. 1937. Imperial Hearst. Greenwood Press edition, 1970. ISBN 083712963X

- Pizzitola, Louis. 2002. Hearst Over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propaganda in the Movies. Columbia Univ Pr.

- Procter, Ben. 1998. William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112776

- Sinclair, Upton. 2002. The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252071107

- St. Johns, Adela Rogers. 1969. The Honeycomb. Signet. ISBN 0451063503

- Swanberg, W.A. 1961. Citizen Hearst. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0883659700

- Wilkerson, Marcus M. 1932. Public Opinion and the Spanish-American War: A Study in War Propaganda. Russell & Russell.

External links

All links retrieved May 12, 2023.

- The Cat's Meow at the Internet Movie Database

- San Simeon, or the Hearst Castle

- The William Randolph Hearst Foundations

- William Randolph Hearst at the Internet Movie Database

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.